Although more books on natural history have been published in the twenty-first century than at any other time, we still tend to think of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the golden age of natural history publication. John James Audubon and James Bateman took their publications to the extremes in size, while Maria Sibylla Merian, Mark Catesby, Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Marcus Elieser Bloch, John Gould, and other naturalist-artists bedazzled their contemporaries with illustrations that are still referenced by scientists today—and much sought after by collectors.

The goal in all of these publications was to record and disseminate information about plants and wildlife, and to provide the most “lifelike” illustrations of the world’s flora and fauna. But a few publications went further, replicating nature in a more tangible way by incorporating the organisms themselves in their pages, or, in the case of trees, using the very subjects being discussed to create the books describing them.

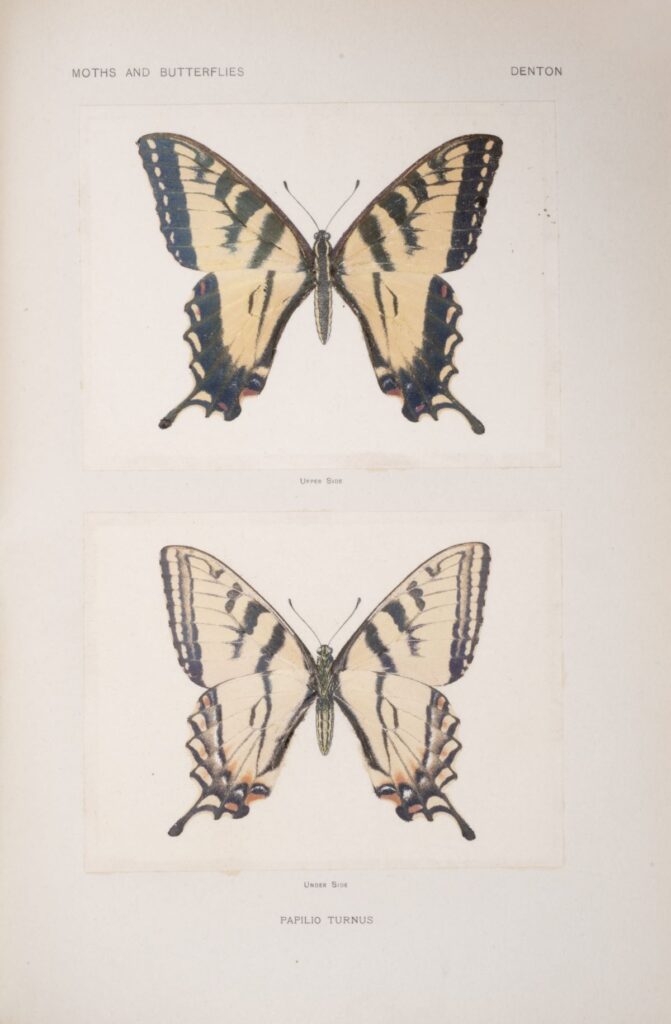

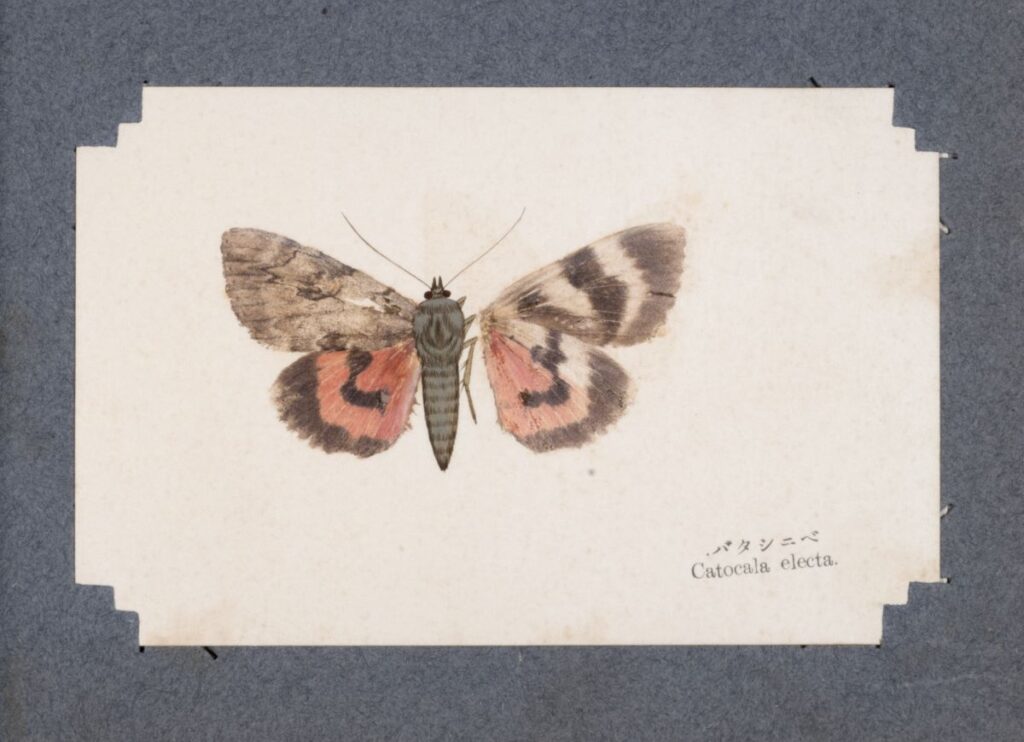

The insect books made in this way are likely the ones that catch our eyes first. In the late nineteenth century and the first few years of the twentieth, two entomologists, one in the United States and one in Japan, used parallel techniques to create lepidochromes—books that illustrate butterflies by attaching the actual scales from their wings to pages on which the bodies of the insects had been printed or painted in advance. In the US, Sherman Foote Denton published As Nature Shows Them: Moths and Butterflies of the United States East of the Rocky Mountains in Boston in 1900 (Figs. 3a, 3b). In Japan, Yasushi Nawa, founder of the Nawa Insect Museum in Gifu, published The Pressed Specimens of Butterflies and Moths between 1908 and 1912 (Figs. 4a, 4b).1

Nawa’s book, of which only a handful were ever made, is in two volumes. They are made up of individual calligraphed cards with the moth and butterfly wings, which were inserted into the pages of pre-bound albums. Denton’s work, published in three volumes, had a much larger edition of five hundred, and along with specimens included many photographic reproductions (in black and white), as well as much more text.

By coating each page surface with a thin layer of glue made from gum arabic, tragacanth, and fish bladder, then transferring the butterfly-wing scales onto it, both Nawa and Denton were able to preserve the structural iridescence of the wings in a way that printing ink or hand-coloring could not achieve. In Denton’s case, the butterfly bodies and antennae were printed from copper engravings and then colored by hand. The bodies for Nawa’s butterflies were each individually hand-painted.

In the preface to his book, Denton described both his technique and the extent of his labors as he traveled widely in search of specimens: “The colored plates, or Nature Prints, used in the work,” he explained, “are direct transfers from the insects themselves. . . . I have had to make over fifty thousand of these transfers for the entire edition, not being able to get anyone to help me who would do the work as I desired it done. I will say, however, that there was never a laborer more in love with his work.”2

The concept of using actual specimens as illustrations can be traced back to the inventor of sottobosco—“under the trees”—painting, the Dutch artist Otto Marseus van Schrieck, who created many forest still lifes focusing on the microcosms of the forest floor (Fig. 5). Instead of painting butterflies and moths, van Schrieck would transfer their scales directly onto the canvas—a conservation technique called lepidochromy.

Since the eighteenth century, botanists around the world have traditionally preserved plant specimens by pressing and drying them, then sewing, gluing, or taping them onto individual sheets of paper to be stored in cabinets. Collections made in this way are commonly known as herbaria. A few ambitious botanists distributed duplicate sets of specimens as herbarium sheets or incorporated the preserved plants into hard-bound, typeset publications. The latter are known as exsiccatae. The oldest example of this technique survives in a book called Herbarium vivum recens collectum made in 1732 by the German naturalist and pharmacist Johann Balthasar Ehrhart (1700–1756). There were a few other such books published in the eighteenth century, but most of the surviving exsiccatae were created in the nineteenth century.

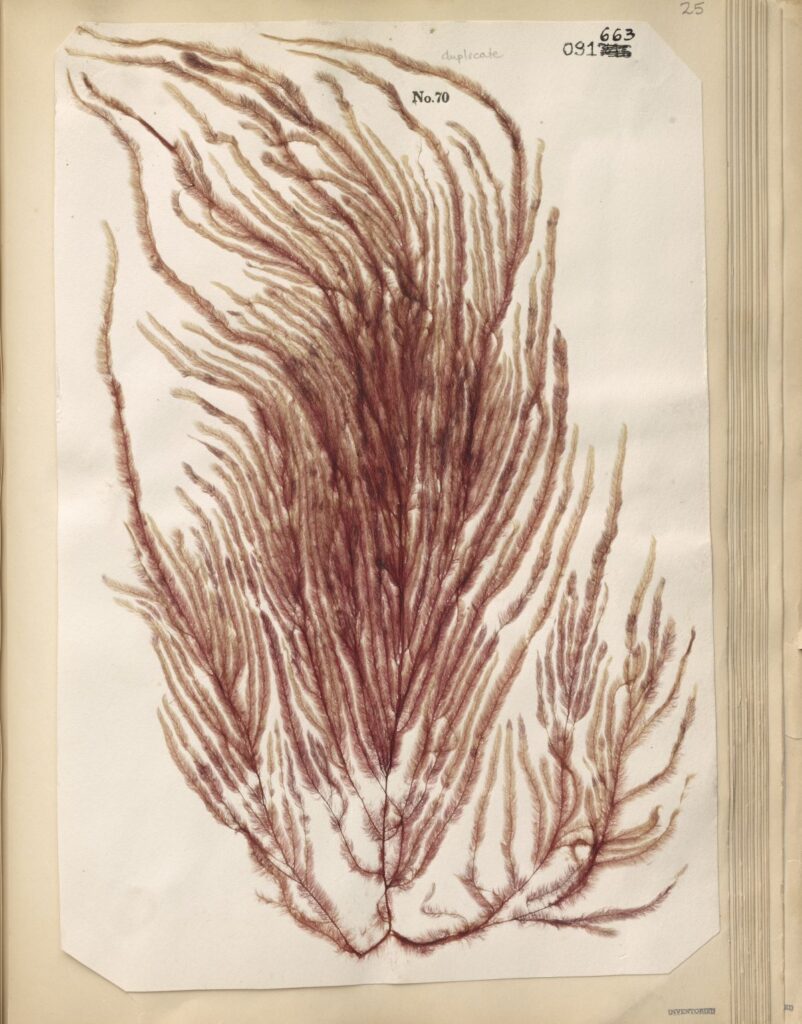

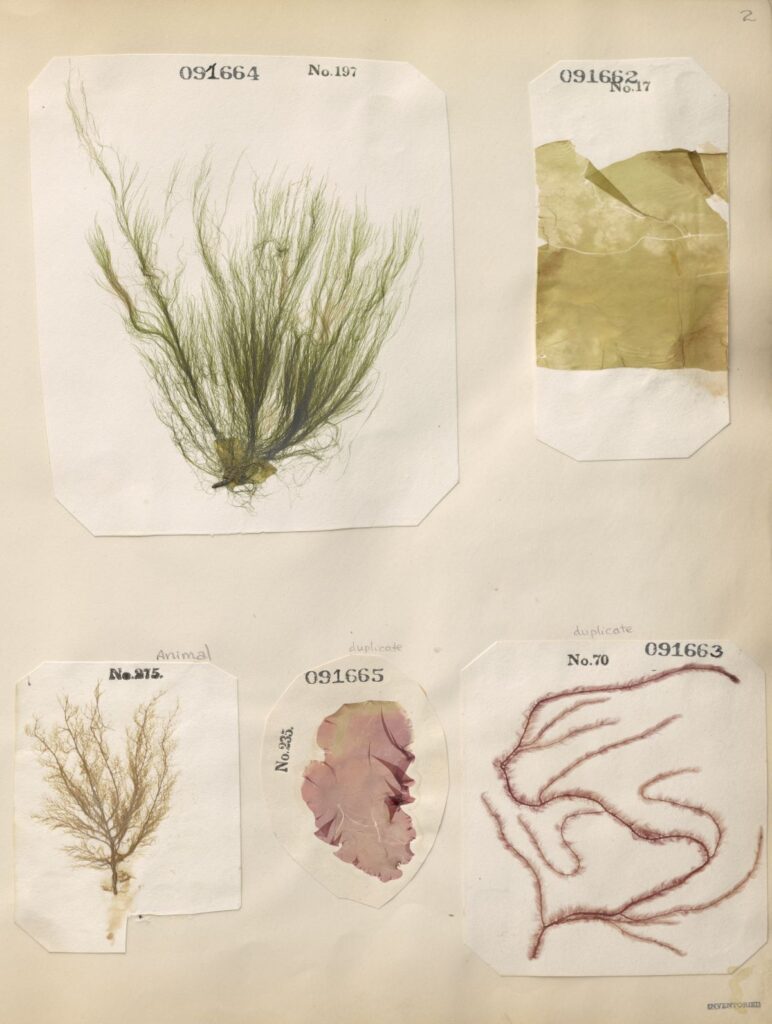

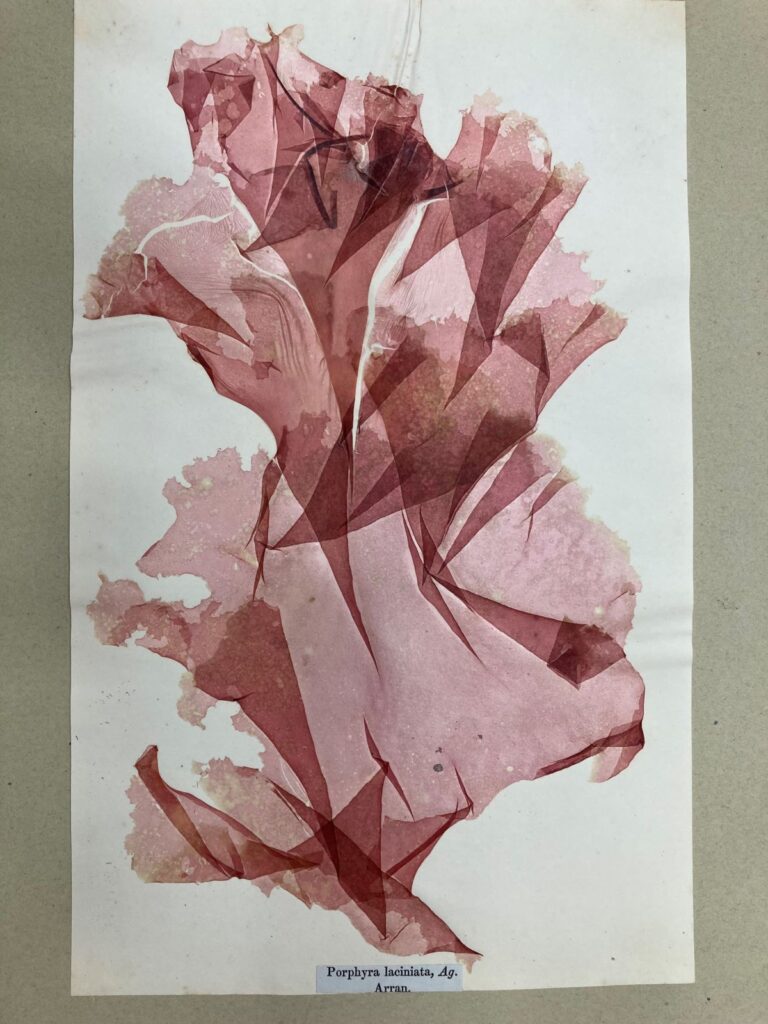

One of the most beautiful of these, which combines printed text and specimens of seaweed and algae, was created by an amateur American naturalist named Charles Ferson Durant in 1850. His book, one of the rarest in botanical literature, has forty-three pages of printed text, and another forty containing specimens of algae from New York Harbor, artfully arranged and mounted on individual cards, four to eight species per page (Figs. 2, 6a, 6b, 6c). The book had an ambitious print run of fifty copies. 3

To assemble the plants described in the text, Durant invested more than twenty-four months of effort. “For two years,” he explains in his preface, “I lived a sort of amphibious life, paddling about the shallows when the tide was out, in quest of specimens.” Although a stockbroker by profession, on some mornings he would rise before dawn, walk the ten minutes from his home to New York Bay, and wade the waters there collecting before having to return to “the business affairs of the day.” At other times, he would visit more “distant shores of the Bay,” and spend “several hours,” or even “an entire day” collecting. “The original design was to acquire at least one of each species indigenous to the [New York] harbor,” he wrote. Quite apart from the years of study that enabled Durant to describe the seaweed in an accurate way, the book he called Algae and Corallines, of the Bay and Harbor of New York took more than two thousand hours of labor—collecting, sorting, identifying, and mounting the specimens. He estimated that he had made over a thousand miles of “perambulations on tidal and sea-shore” to create his life’s work.4

David Landsborough, a Scottish clergyman, had the same idea at almost exactly the same time. In 1847 he created an exsiccata titled Treasures of the Deep or Specimens of Scottish Sea-weeds; Natural Order: Algae (Figs. 7, 8). There are fewer than a dozen copies of this book in existence—six in public libraries in the United Kingdom and a few in the United States.5 Although all have twelve pages, with thirty-two printed labels, some have at least forty-five specimens, with the added specimens identified with handwritten labels. The book has a printed title page, and printed specimen labels, but no text. Landsborough’s more widely distributed Popular History of British Seaweeds, which went through three editions between 1849 and 1857, was illustrated in a more conventional way with lithographs.

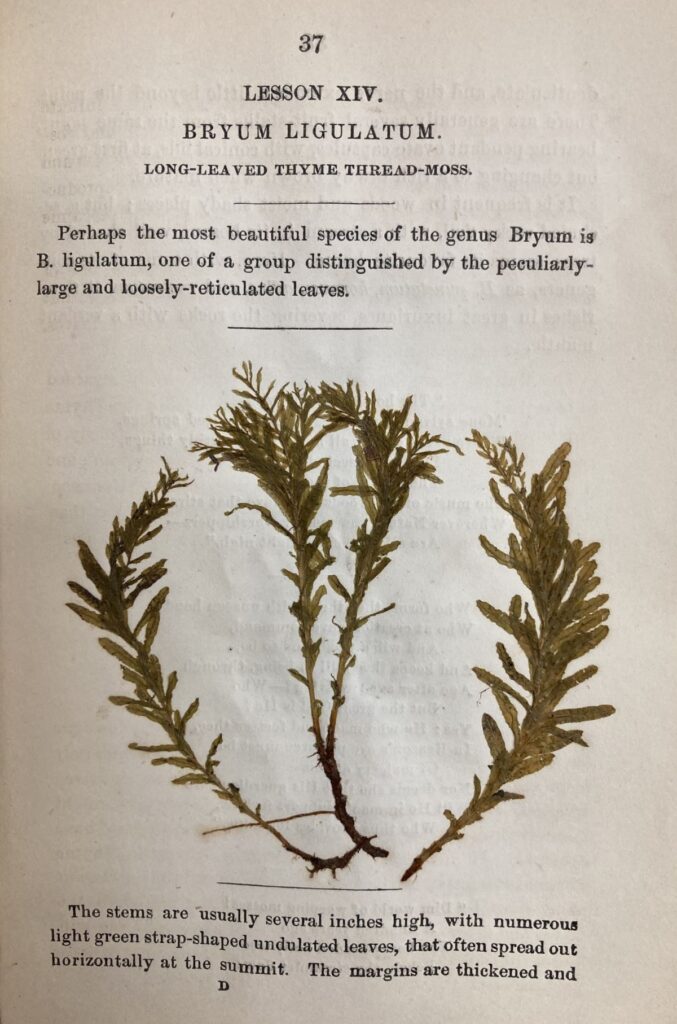

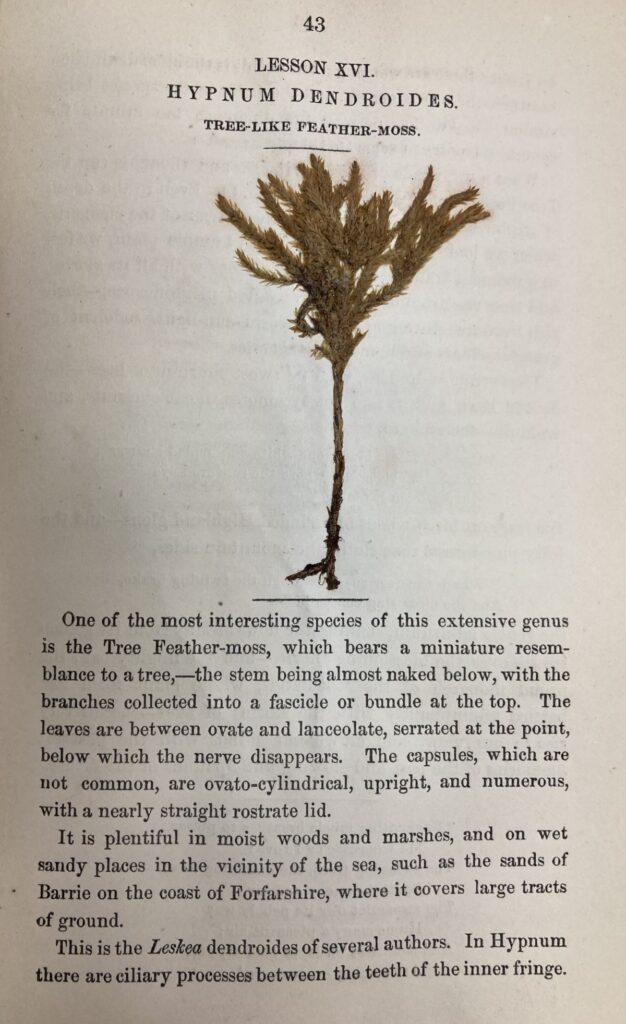

Another mid-nineteenth-century exsiccata with a limited print run was William Gardiner’s Twenty Lessons on British Mosses (Figs. 9a, 9b). “The idea of illustrating the subject with real specimens, instead of engravings, is not a new one,” wrote the author in his preface, “but it must be allowed to be more effective, for the works of Nature are always superior to the imitations of art, and the eye can more readily recognize a plant in the growing state by this means, than by the most careful delineations of the pencil.”6

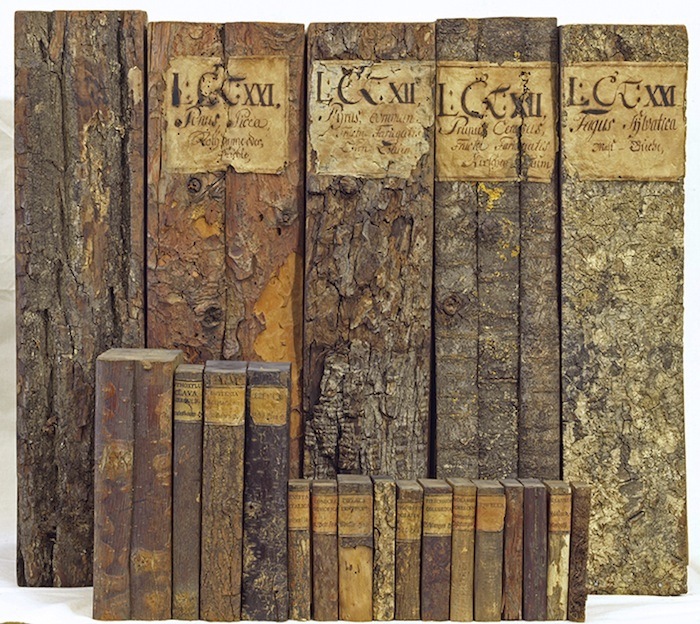

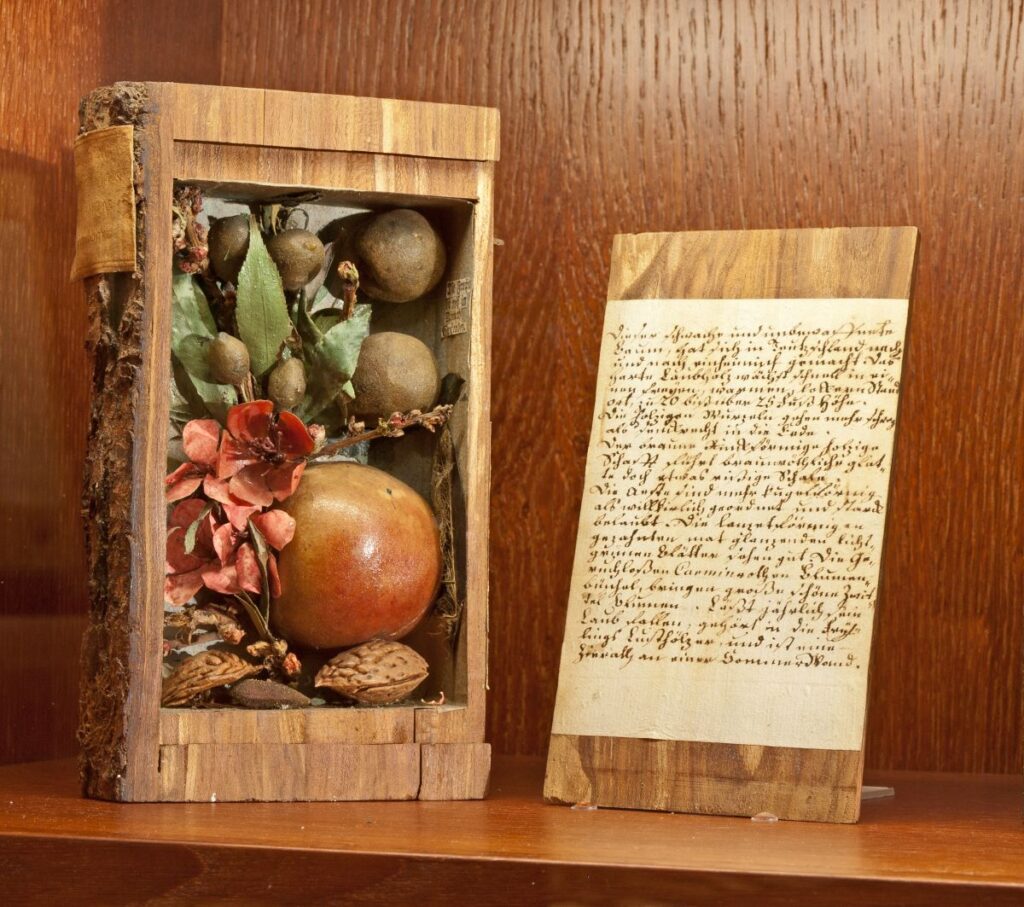

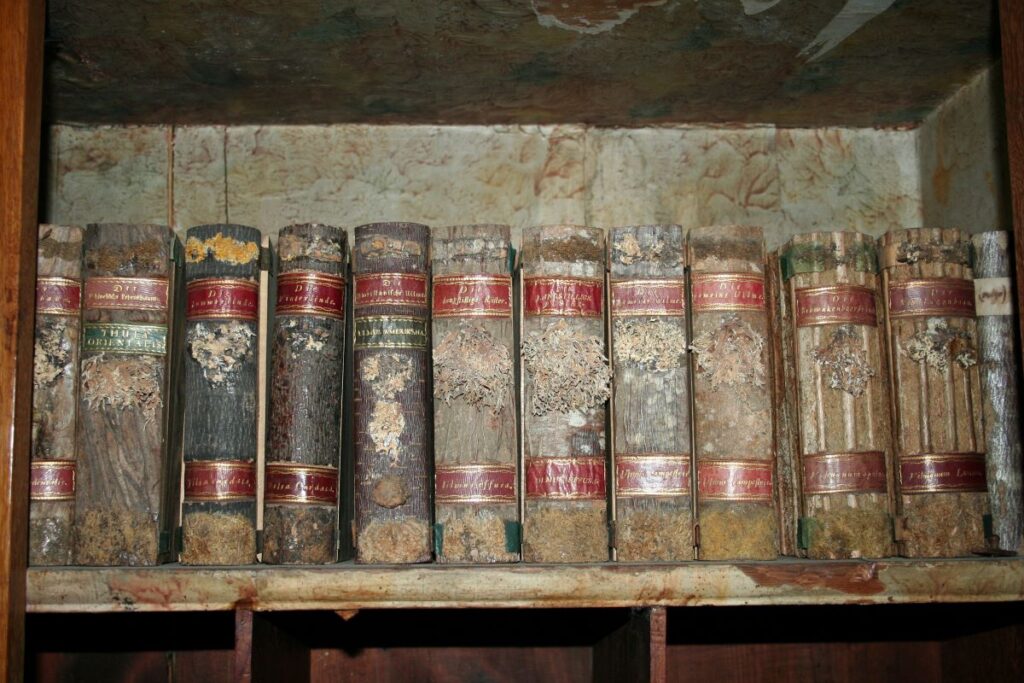

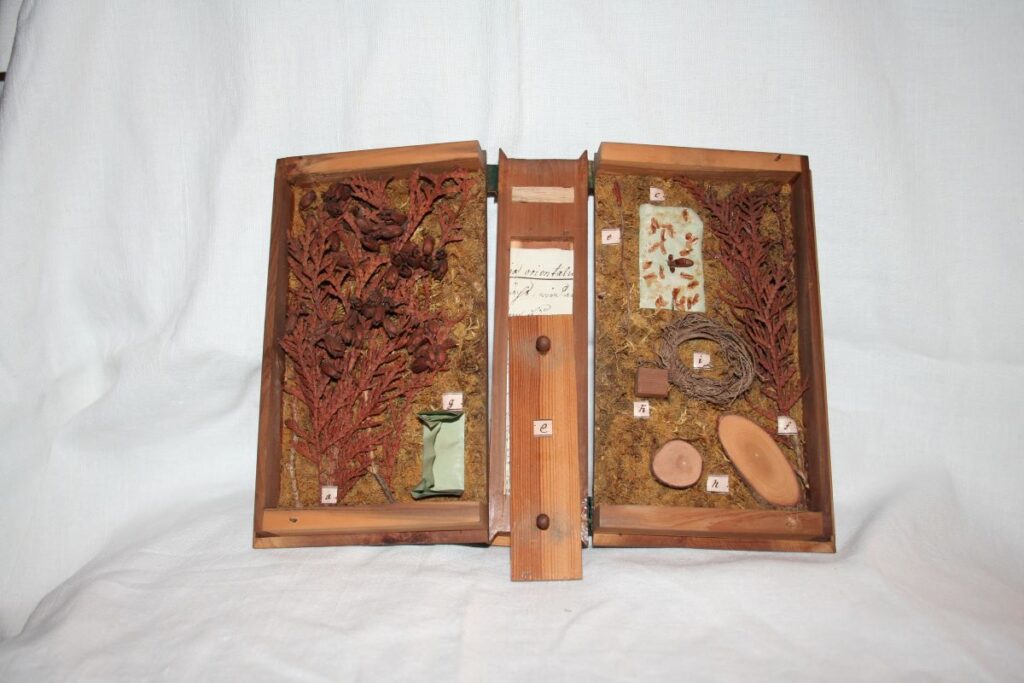

A tree can be documented by mounting thin sections sliced from the trunks and branches on the pages of a book. Trees can also be documented by turning the wood itself into a three-dimensional record. A small number of “libraries” composed of such books, known as “xylotheks” (sometimes spelled xylotheques), were produced in Europe in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The first and most comprehensive was created between 1771 and 1779 by Carl Schildbach, a German naturalist who worked as the manager of a menagerie on the estate of the landgrave of Hesse-Kassel in central Germany (Figs. 10a, 10b, 10c).7 Although he lacked a formal education, Schildbach created one of the most remarkable wooden libraries ever produced. It consisted of 546 boxes of various sizes styled to resemble books. The size of each volume was determined by the relative size of the tree being discussed and the durability of the wood used in its construction. The resulting wooden “books” were made in folio, octavo, and duodecimo formats. The spine of each was made from the bark of the relevant tree, and features a label made from a leather band that delineates the tree’s Latin name, its common name (in German), and its Linnaean classification number. The front covers were made of sapwood, the back covers of heartwood, cut lengthwise to exhibit the grain. The top edges were made from the cross sections of young branches to show the tissues of the tree in its early stages of development. The bottom edges were made of mature heartwood.

As useful as the books are in identifying trees, their contents hold even more information, which is also conveyed in three-dimensional form. The front cover of each one slides open to reveal a chamber in which various specimens document the tree in its different stages of life. These include twigs, dried leaves, seeds, fruit (either dried or made of wax), and a handwritten description of the tree, discussing its many attributes and life cycle. The Schildbach library represents 120 genera and 441 species of trees, most of which grew on the properties for which the books’ creator had managerial responsibility. In 1788 Schildbach printed a pamphlet to accompany his handiwork.8

Despite the attention and admiration his unusual creation drew from foresters and botanists across Europe, Schildbach was determined that his books would not travel. He declined an invitation to take his tree library to Paris and refused to sell it to Catherine the Great of Russia, who at the time was assembling a great library on the wonders of the natural world. In the end, he gave it to his patron, the landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, in exchange for a pension. It remains in Kassel today, in the Ottoneum Natural History Museum, where it is presented in a cabinet constructed by the American artist Mark Dion in 2012 as part of the quinquennial art exhibition series Documenta.

Another library of wooden books can be seen at the Strahov Monastery in Prague. Prepared by Carl von Hinterlang about 1825, it consists of sixty-eight volumes (Figs. 11a, 11b). Unlike Schildbach’s library, the wooden “volumes” are all the same size—octavo—but their spines are likewise covered with the appropriate bark festooned with lichens. Inside each book are the roots, branches, pressed leaves, flowers, and fruits of the species being documented.

Other xylotheks can be found in the House of Lobkowicz collection in the Czech Republic, and at Kremsmünster Abbey in Austria. Most wood libraries come from the European workshops of Hinterlang, Candid Huber (1747–1813), Friedrich Alexander von Schlumbach (1772–1835), and Johann Golle. A list compiled in 1997 by the Museum der Sternwarte Kremsmünster in Austria identified forty-four extant wood libraries in Europe, though a few more have been found since.9 A recent survey has found none in North America.

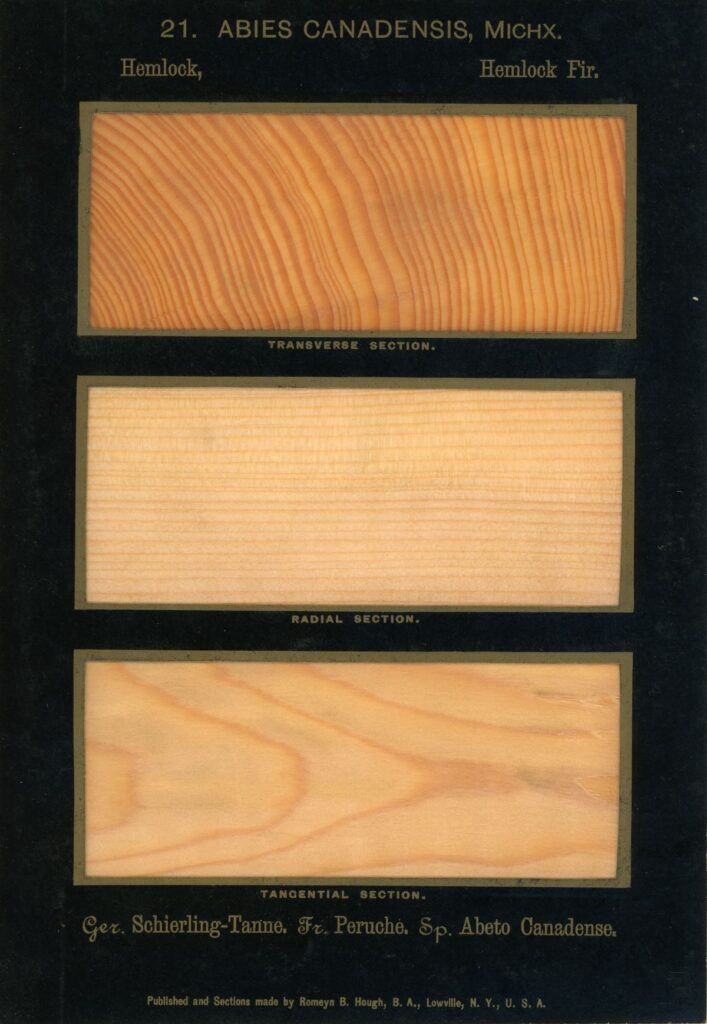

Books containing, but not made from, original wood samples were published by a number of authors, the best known of whom was the American botanist Romeyn Beck Hough (Fig. 12). These had larger print runs than the one-off volumes in xylotheks but were no less time-consuming to create. Hough issued thirteen volumes of The American Woods between 1888 and 1913.10 They contain paper-thin cross-sectional slices of wood made using a machine that Hough himself patented. To each tree, he dedicated a cardboard sheet containing three slices—transverse, radial, and tangential sections—of the wood. These were accompanied by a text about the botany, habitat, and medicinal and commercial uses of the species represented. In total, each volume contained at least twenty-five plates, and the complete fourteen-volume collection comprises 1,056 slices representing 354 tree species. The American Woods received a grand prize at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, and gold medals at the World’s Columbian, Pan-American, Louisiana Purchase, and Alaska Yukon expositions. For antiquarian book collectors, The American Woods is one of the most sought-after publications of the twentieth century. In 2000 Christie’s sold a complete set for $92,100.

Given the amount of time and effort required to create any of the specimen-based collections described here, and the world’s current sensitivity to the loss of biodiversity, it is unlikely that any comparable things will be made in the years to come. We can only marvel at the devotion to science and art that resulted in these remarkable artifacts.

1 Chôga rinpun tensha hyôhon is the Japanese printed title. 2 Sherman Foote Denton, As Nature Shows Them. Moths and Butterflies of the United States East of the Rocky Mountains (Boston: Bradlee Whidden, 1900). 3 Michele Currie Navakas (“A Book full of Seaweed,” April 1, 2018, online at huntington.org) states that only about fifteen copies of the book were completed with specimens, but I have been able to locate thirty-one copies in the US alone. Presumably, there are more overseas. 4 C. F. Durant, Algae and Corallines, of the Bay and Harbor of New York (New York: George P. Putnam, 1850). 5 Although most of these books were published in Glasgow by David Bryce in 1847, there is at least one copy of an 1853 edition (at the University of Edinburgh).6 William Gardiner, Twenty Lessons on British Mosses . . ., 4th ed. (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans; Ackerman and Company, 1852), p. 6. 7 For more on wood libraries, see Alice Goff, “The Selbst Gewählter Plan: The Schildbach Wood Library in Eighteenth-Century Hessen-Kassel,” Representations, vol. 128, no. 1 (Fall 2014), pp. 30–59. See also Bonnie Mak, “Wood Libraries: Knowing with Wood and Work,” Caxtonian, Journal of the Caxton Club, vol. 39, no. 3 (May–June 2021). For other recent descriptions of the Schildbach wood library see Arthur MacGregor, Curiosity and Enlightenment: Collectors and Collections from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). 8 It was titled Holz-Bibliothek nach selbst gewähltem Plan [Wood Library According to Self-Determined Plan]. 9 ‘‘Objekt des Monats: Die Xylothek,’’ available at specula.at. Additional wood libraries have been recently identified in Frauenfeld, Switzerland, and Hamburg, Germany. See Anne Feuchter-Schawelka, Dietger Grosser, and Winfried Freitag, Alte Holzsammlungen. Die Ebersberger Holzbibliothek: Vorganger, Vorbilder und Nachfolger (Ebersberg, 2001). 10 Hough had originally intended to produce fifteen volumes, but died before the project could be completed. A final, fourteenth volume was published in 1928 using samples and notes made by Hough that were compiled by his daughter, Marjorie Galloway Hough (1896–1972).