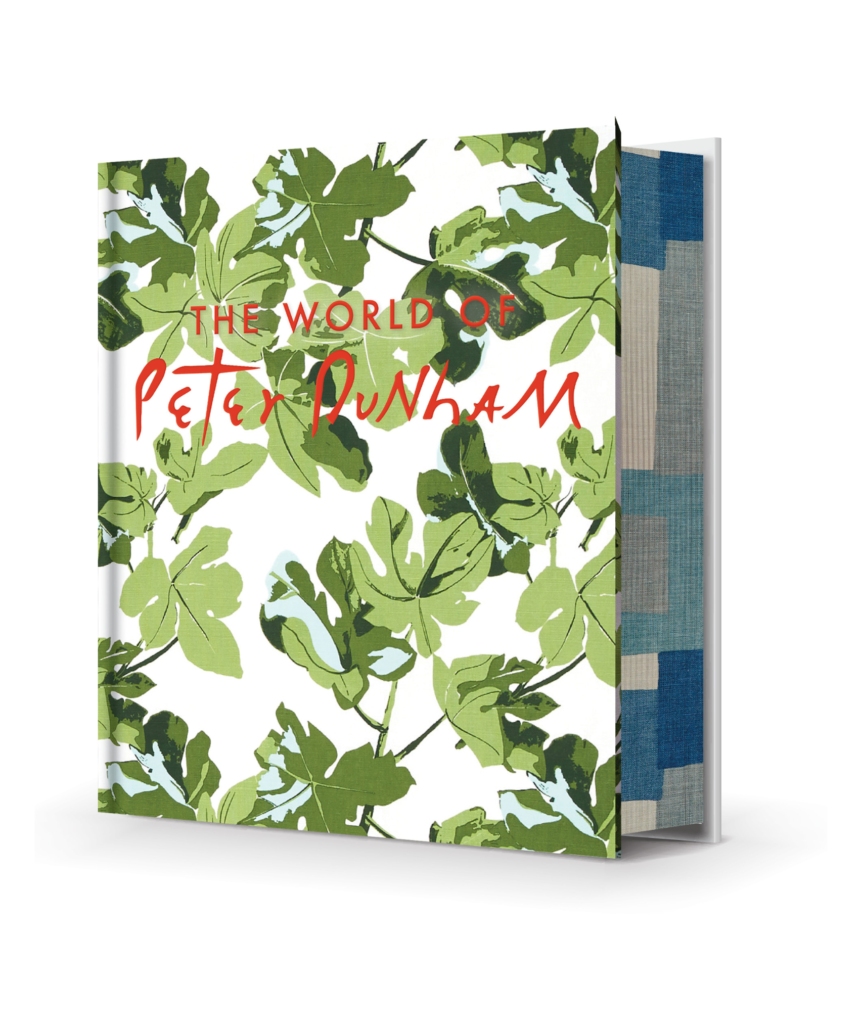

The World of Peter Dunham: Global Style from Paris to Hollywood, from Vendome, features Dunham’s iconic fig-leaf patterned fabric on the cover. The design was inspired by a visit to the house of his next-door neighbor, Salvador Dalí, and encapsulates a life dedicated to the pursuit of very personal and informed style. The book illustrates how he has translated and imported an unusually cultured life into the homes of his clients as well as lines of fabrics and

homewares, all reflecting his nomadic explorations.

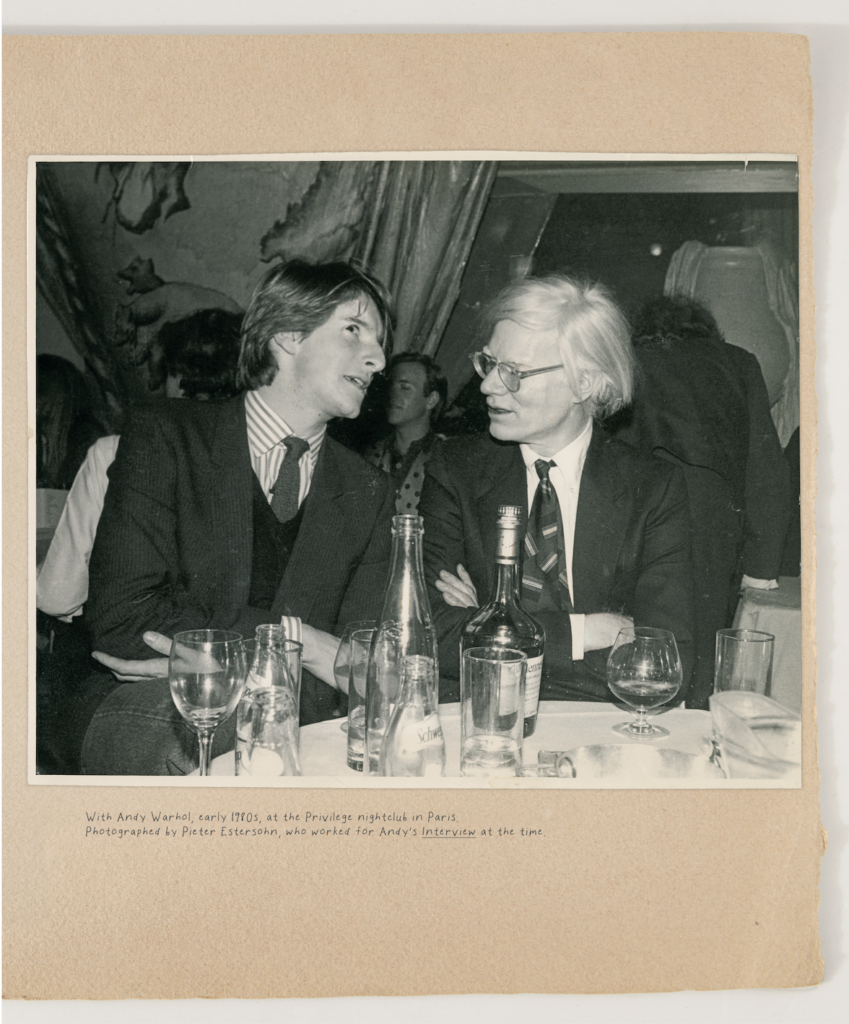

On a recent stopover in Manhattan, Peter (we met when we were eighteen and I was working at Andy Warhol’s Factory) came over to my place to discuss his new book. During coffee, I was reminded that all the experiences I undoubtedly hear about when we reconnect have directly contributed to his having one of the most rarified eyes in a business saturated with them.

Before the “boho-chic” trend, Peter was journeying to India and returning with magnificent textiles, many of which have inspired and informed his present textile line. While many designers visit magnificent country houses, Peter lived in them. He has, from infancy, had art world exposure like very few, and the entire scope of his escapades and relationships have synthesized into his ability to see when simplicity must reign supreme and when adding more layers is called for.

In his new book, Peter dedicates spreads to early friends and mentors in the business, including Jacques Grange, Teddy Millington-Drake, and David Hicks, traces of whose influence can be detected throughout the pages. Peter offers a great synthesis of his early exposure in Europe and the more relaxed vibe he now references as the soundtrack for each house he works on. There may be fewer decorating rules in Los Angeles, but you still need to know the history of your métier to pull it off successfully. The cavalcade of color saturation, unusual juxtapositions, and beautifully referenced patterns create his very distinctive signature style.

When I mention classicism, the loose theme of this issue, Peter delves into memories of the seventeenth-century neoclassic Hôtel de Noailles designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart that he grew up in at Saint-Germain-en-Laye before his family moved into an art deco masterpiece in Paris. “Growing up in Paris taught me about beauty in the most classical, pure sense,” he explains.

“Symmetry, proportion, the power of architecture or decorative motifs—as fun and serendipitous as my interiors may seem, they are absolutely rooted in classic tradition.” Dunham sprinkles classical bergères and fauteuils into many of his projects and often incorporates French furniture from the 1940s, much of which references the eighteenth century.

He also spent many formative years at Stowe, the British school housed in the Duke of Buckingham’s country house. “My mother chose my schools by their looks,” he says. “As we were first progressing down the three-mile-long drive with double-lined, three-hundred-year-old elms that leads to Stowe, I heard my mother gasp and I knew that this was where I’d be going to school.”

While at school, Peter would take his pocket money and go into the village. “The only thing that excited me at fourteen was these tiny antiques stores. I still have some of the things I found then, but I really became interested in collecting while on vacation back home in Paris. Hôtel Drouot was then in the Gare D’Orsay, and there was an impossibly long corridor with all the dealers and auction houses lining both sides. It was intoxicating. I would return home, and my mother would mutter, ‘Please, no more single chairs.’”

“I love the poetry of the almost feral hunt for an object. We often moved houses, I was away at school, so perhaps collecting grounded me and let me create my own roots. What really shook me up was traveling to the Orient and India. I was impassioned by the culture and history; the textiles made me insane.” Peter has translated many of the patterns he saw and collected during these trips; throughout his book, the reader can see wonderfully intricate and evocative prints upholstering his furniture and even the walls in his densely layered rooms.

This eclectic collector’s inclinations are clearly seen as one turns the pages of the book, starting with an early flat photographed for Elle Decor. The combinations of exotic references and objects that just happen to work together in an unprecedented manner all speak to a life refining, from a design perspective, what resonates both culturally and historically. In reference to the earlier mentioned English country aesthetic, there is a thread that runs through Peter’s work that parallels that of the Society of Dilettanti, the eighteenth-century cabal of English milords who traveled the Continent following graduation to deepen their understanding

of history and add to their families’ collections.

The English houses became layered repositories of lives well-traveled in the same manner that Peter seamlessly

layers exotic references. As we part ways, Peter sums up the synergistic relationship between a life researching different cultures and a career dedicated to passing it forward, “My business now feeds my addiction.” Not a bad goal.