What is folk art? You think you know what it is, then discover that it’s surprisingly hard to define. The term “American folk art” is a cultural construction. Historically, folk art has been classified as art that is non-academic, amateur, self-taught, primitive, rural, and/or vernacular, as well as often utilitarian in nature. Yet these labels only characterize “folk” art as what it is not: not high-style, urban, fine, or academic. American artists and makers of the past never used the word “folk” to describe themselves or their work. Folk art is a category of American art invented, and continually reinvented, by modern artists, collectors, dealers, curators, and art historians over the past century. In reality, the changing definitions of folk art reveal more about the values, needs, and desires of the community doing the defining than they do about the individual artworks themselves.

Collecting Stories: The Invention of Folk Art, an exhibition now on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, explores these different perspectives and interpretations through a re-examination of works on paper and sculpture primarily from the MFA’s Karolik Collection of American art (Fig. 1). This exhibition marks the beginning of the museum’s multi-year initiative to explore ways to better understand, display, and interpret artwork previously labeled folk art in a manner that acknowledges the multiple interpretations of the objects over the years and best suits the needs, desires, and values of today’s society.

A number of American modern artists working in the early twentieth century, including Marsden Hartley and Charles Sheeler, sought to identify a distinctive national artistic heritage, free (or so they thought) from European influences. Many looked for inspiration in artworks and objects that supported a romanticized view of past and present rural or Indigenous American life. They admired the graphic silhouettes, flattened perspective, bold color contrasts, and exaggerated proportions they found in the work of itinerant painters, hobbyists, and skilled artisans— artists free from the strict rules of academic training and impelled by trade, craft, community, creative impulse, or affirmation of identity. By heralding the aesthetic qualities of these works, the modern artists, together with associated collectors, museum professionals, and dealers, invented a new category of art that came to be known as American folk art.

One such collector was Maxim Karolik, a Russian opera singer who entered Boston society on his marriage to Brahmin heiress Martha Codman. Karolik brought the new trend in collecting American folk art to the MFA in the 1940s, and championed the then-radical notion of incorporating folk art within an encyclopedic art museum’s collection—shaking up established standards of “fine” art. He even challenged the arbitrary classification of folk art, stating “one wonders whether, from the artistic point of view, the question of Folk Art versus Academic Art has any meaning. In my opinion, it has none. The question I continue to ask is whether lack of technical proficiency limits the artist’s ability to express his ideas. I do not believe that it does.”1

Maxim Karolik wanted his collection to represent the full spectrum of American art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “to reveal, through art, the heartbeat of a nation.”2 He introduced popular nineteenth-century forms, materials, and techniques into the MFA collection, as well as newly recognized artists, such as itinerants, hobbyists, students, women, and those from rural and poor communities who brought new perspectives on American life. These powerful works not only challenge us to question the definitions of art but they also offer rare insight into the artistic lives and creative impulses of “ordinary” Americans, as well as the motivations and goals of the collectors who deemed them worthy of inclusion in the museum’s collection. A sampling of the stories featured in the exhibition is offered below.

Although MFA curators at first balked at the unconventional or unsophisticated nature of these works, they came to accept Karolik’s expanded vision of American art. However, Karolik proved to be ahead of his time—while MFA curators ultimately accepted the value of “folk” art, they remained reluctant to display it alongside the so-called “fine” art in the collection for decades to come.

In general, over the course of the past century, the term “folk art” inadvertently has become a convenient, but inaccurate and sometimes disrespectful, umbrella term to classify any work created by an artist outside the traditional art historical canon, lumping together pieces by women, African Americans, Latinos, and rural, poor, and Native communities, among others. Despite its democratic roots, folk art has become a term of exclusion rather than inclusion.

Now, at the MFA, we acknowledge that although Karolik’s collection was expansive, it was not inclusive in the modern sense of the term—it reflects what was readily available, as well as the prejudices held in the mid-twentieth century. It lacks work by Black, Latin American, and other underrepresented artists of the nineteenth century.3 In the past sixty years, the MFA has made efforts to rectify those omissions, while also advancing the story further into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by acquiring art often referred to as “outsider” or “visionary.” We include a small selection of these works in the exhibition. However, we admit that there is still much more work to be done. We also acknowledge that we continue to display works traditionally labeled folk art apart from the rest of the museum’s collection.

Some Highlights from the Exhibition

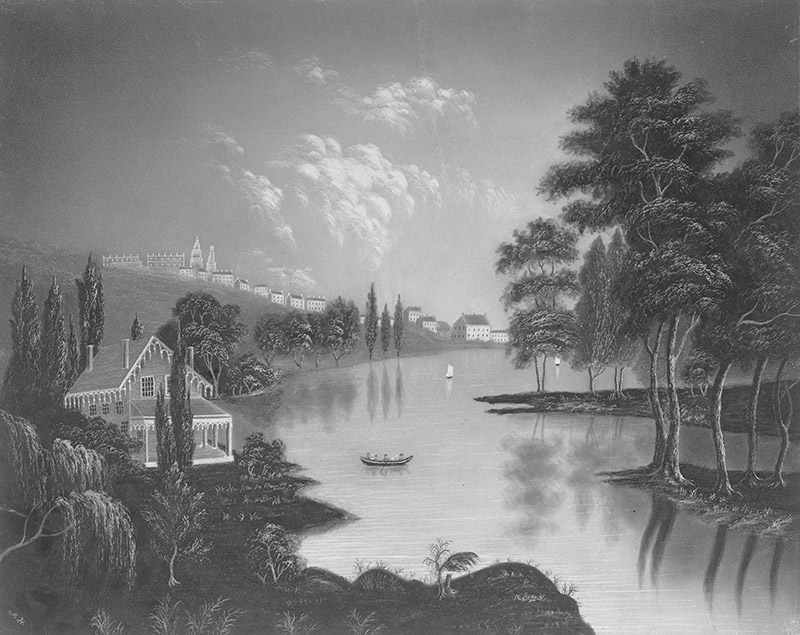

House by the River, possibly by M. T. Harvey, c. 1850

The artist who made this image used a popular nineteenth-century technique now referred to as sandpaper or marble-dust drawing, in which a board is prepared with white paint and sprinkled with glittering marble dust. Once dry, charcoal and/or pastel colors are applied to the surface and manipulated with sharp tools and soft leather to create forms revealing the shimmering white layer underneath. First introduced in the US by an 1835 British art instructor’s book, the technique’s popularity grew through itinerant artists, academies, and art supply stores.4

This scene is based on the print Albany, From Van-Unsselaens [Van Rensselaer’s] Island, published in volume 2 of The History and Topography of the United States in 1832.5 The print itself likely reproduces a painting by Irish-born American landscape artist William Guy Wall (1792–after 1864). Yet, the artist of the drawing replaced the print’s simple building with an elaborate Gothic residence. Similarly, a leisurely boating party substitutes for the shallow ferry carrying livestock across the river. The artist did not wish to create a verbatim copy of the print, but instead used it as inspiration to create his or her own interpretation. The 1962 two-volume catalogue of the Karoliks’ collection of American watercolors and drawings lists this marble-dust drawing as by “?M.T. Harvey,”6 although nothing more is known about this potential artist’s identity.

Works such as House by the River reveal the democratization of visual culture in the United States in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With the advent of improved printing technologies, expanded transportation and communication networks, and the invention of photography, art was no longer the sole purview of the elite. Printed images circulated widely, serving as inspiration for highly individual artistic interpretations. Although these so-called “folk” versions were often created with less technical skill, their personality, raw emotion, and creativity often make them more engaging than the original academic model.

Squirrel and eagle by Wilhelm Schimmel (1817–1890), 1860–1890

Although Karolik initially focused on paintings and drawings, his curatorial partner at the MFA, prints and drawings curator Henry P. Rossiter, encouraged him to pursue sculptural forms as well. Rossiter particularly liked the work of nineteenth-century German immigrant Wilhelm Schimmel, a colorful character who lived in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, and who traded his carvings for food, shelter, and copious drink. In 1953 Rossiter wrote to legendary art dealer Edith Halpert, “Schimmel really gets me.” He then proceeded to announce his intention to encourage Karolik to acquire “about 20 more sculptures” to complement his collection of watercolors and drawings.

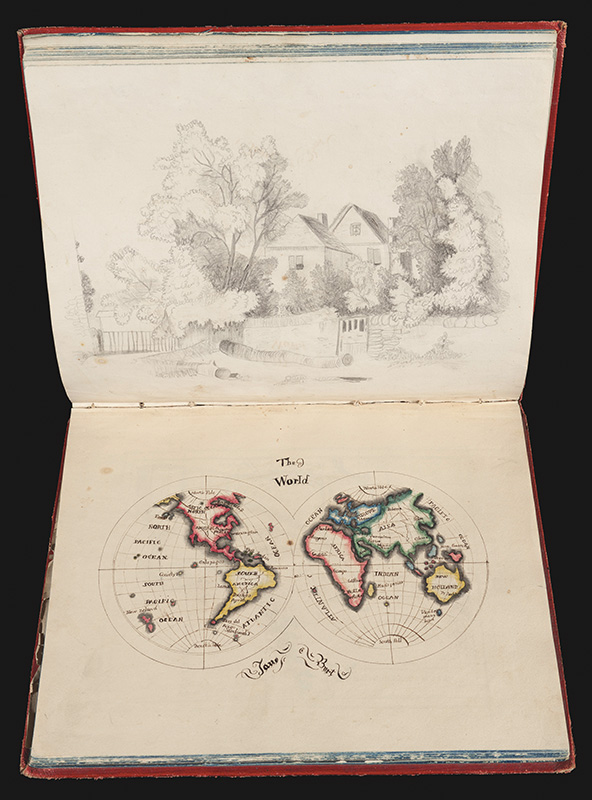

Book of penmanship by Jane M. Burt (1822– 1850), 1835

In 1835, at age thirteen, Jane M. Burt made this “Book of Penmanship” at Miss Leverett’s School for Young Ladies in Rutland, Vermont. Burt not only practiced her pen control on its pages, but in the process recorded geography, buildings, flowers, and genre scenes in both freehand and stenciled drawings.

The curriculum in female academies in the early nineteenth century differed drastically from that of young men; instead of learning classical languages, girls studied literature and domestic arts. Skills in penmanship, drawing, and needlepoint reflected a young woman’s social prowess and served as a sign of her higher education. Map drawing, such as the elaborate depictions of New England and the world in Burt’s book, allowed students to practice their artistic skills while ingraining knowledge “to prepare them for a life of usefulness and social exchange.”8

The similarity of Burt’s album to earlier examples from other Vermont schools—one from Middlebury Female Academy (1823) and two from “Mr. Dunham’s School” in Windsor (1818, 1819)—may reveal a closer connection than the standardized approach to educating young women.9 Miss Leverett could be Caroline Hollam Leverett, born in Windsor, Vermont, in 1804. Perhaps she attended Josiah Dunham’s Windsor school, and had her own book of penmanship that served as a model for her own students.

Lion Rampant by Sam Katz 1885–after 1924), 1922–1923

In 1907 Sam Katz, a Jewish woodworker, immigrated from Ukraine to the United States with only five dollars in his pocket. Today, he is recognized as “the greatest and most prolific Jewish maker of Torah arks in all of American Jewish history.”10 Katz carved and gilded this lion to stand atop the Torah ark at synagogue Anshai Poland in Boston’s South End. The lion and its companion (now lost) protected Anshai Poland until 1957, when the building was sold to the Boston Housing Authority and ultimately destroyed. Prior to its demolition, the ark was dismantled and sold in parts to various local dealers, transforming the lion from a sacred symbol into a secular sculpture to be purchased three years later by Maxim Karolik, for his American folk art collection.

A Torah ark is a synagogue cabinet that houses the Torah scrolls, handwritten with the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. The ark is the most sacred space in the synagogue and features ornamental motifs including symbolic imagery of lions, the Decalogue (tablets of the Ten Commandments), an eagle, a crown, and open hands. In Jewish iconography, lions represent the tribe of Judah and symbolize strength and courage. The Decalogue guarded by confronting lions became the most popular imagery on American Torah arks.

Group of Merino Sheep by Noah Wesley Wineland (1856–1929), after 1879

When one thinks of portraits, sheep are not generally the first image that comes to mind. Livestock portraits were the ultimate display of wealth in nineteenth-century Britain, where this tradition began. These portraits acted as part art, part advertisement for the excellent breeding of both the animal and its owner. Merino sheep, who grew a soft, fine wool, were introduced to the United States in the early nineteenth century. By 1860, Ohio, where this portrait was made, was one of the nation’s leading manufacturers of wool.

Based in Centerburg, Ohio, Noah W. Wineland worked as an itinerant portrait painter and spent significant time painting livestock and buildings on farms in central Ohio and northern Indiana. Despite his obvious skill, by 1900 Wineland had moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he opened a photography studio, specializing in portraits, but this time his subjects were people.

The Orphans by Harriot Sewall, 1808

Memorial pictures became a popular mourning custom after the death of George Washington in 1799. Such artworks—often made by young women at home or as part of a school curriculum—frequently featured a tomb or grave, weeping willow trees, and sorrowful relatives, commonly recognized symbols of death. In this example signed by Harriot Sewall, a young boy comforts a girl; they sit under a weeping willow next to a cemetery and are overseen by a female guardian whose exaggerated scale emphasizes her power over them. Orphans, or children without parents trying to make it on their own, were common literary metaphors in the early nineteenth century, as the young United States was adapting to its new independence.

Specific aspects of this image, including the tombstones and architectural details suggest that this watercolor may be of a precise location. The Orphans was painted in 1808 when Harriot was a young schoolgirl in Meriden, Connecticut. The image could depict Waterbury, a neighboring town, as the church in the background strongly resembles Waterbury’s Congregational Church, built around 1795.11 Is this a scene inspired by literature, or a scene from real life? Perhaps the guardian is Harriot herself; unfortunately we might never know.

Our President, Old Hickory (President Andrew Jackson) by James Hosley Whitcomb (1806–1849), 1830

This work bears the inscription “Cut with scissors and painted by J. H. Whitcomb in 1830” at the bottom. James Hosley Whitcomb, a deaf itinerant artist, used watercolor and ink to embellish his silhouettes. This collaged image depicts Andrew Jackson, who earned a reputation as a formidable soldier, attorney, plantation owner, and statesman before being elected president of the United States in 1828, just two years before this image was created. Whitcomb’s glorifying image shows Jackson confidently seated on a horse, dressed in the uniform he wore during the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, with a banner that reads “Our President, Old Hickory,” the affectionate nickname given to Jackson by his soldiers.

Today, the legacy of Andrew Jackson is more controversial than this triumphal image suggests. He is condemned for his role as a prominent slave owner and anti-abolitionist, as well as for his brutal treatment of Native Americans in the Creek War, Seminole Wars, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and his greatest controversy—the notorious “Trail of Tears.” Whitcomb’s use of silhouette, in which Jackson’s features are erased and he is depicted with a black face and hands, can now be interpreted in a very different way that reflects today’s critical thinking about race and representation. It brings to mind questions such as: What happens when a white, historically heroic figure, is deconstructed and represented with a darkened skin tone? And how do we address the actions of political leaders through art?

Los Tres Reyes Magos a Caballo (Three Kings on Horseback) Puerto Rican, 1900–1940

The custom of creating santos, or devotional figures, originated in Spain as early as the sixteenth century, ultimately spreading to Spanish colonies across the globe. Santos became a key tool in Spanish efforts to convert the Indigenous peoples of the Americas to Roman Catholicism as the imagery transcended language barriers. Distinct traditions developed as cultures mixed in various regions of the New World. In Puerto Rico, these cultures included Caribbean, Latin American, and African, in addition to a range of European nationalities— not just Spanish, but French, German, Corsican, and Irish as well.

The use of santos for home-based devotion flourished in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico, when a dramatic rise in immigration to the island pushed impoverished residents to more remote areas. For many, these small, hand-carved sculptures representing saints or holy figures served as intermediaries between earth and heaven, to whom they prayed for protection, help, or guidance. Today, santos are considered one of Puerto Rico’s oldest traditional art forms.

New York art collectors Walter and Lucille Fillin donated Los Tres Reyes to the MFA in 1973, diversifying the voices and perspectives found in the Karolik Collection.

The Invention of Folk Art is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through January 9, 2022. This is the third in a series of three exhibitions funded by the Henry Luce Foundation that uses understudied works from the MFA’s collection to address critical themes in American art and the formation of modern American identities.

1 Quoted in M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1949), p.xi. 2 Perry T. Rathbone, Foreword, M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Water Colors and Drawings 1800–1875 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1962), p. 13. 3 One notable exception is the pictorial quilt by African American artist Harriet Powers that Karolik acquired in 1961. 4 B. F. Gandee, The Artist or, Young Ladies’ Instructor in Ornamental Painting, Drawing, &c. . . . (London: Chapman and Hall, 1835). 5 With thanks to Randall Holton who brought this print source to our attention and the identical drawing in the Randall and Tanya Holton collection. 6 M and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800–1875 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1962), vol. 2, p. 191. 7 Henry P. Rossiter to Edith Halpert, October 28, 1953, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Art of the Americas Object Files. 8 Susan Schulten, quoted in Betsy Mason, “All Over the Map: 19th-Century Schoolgirls Were Incredibly Good at Drawing Maps,” National Geographic, published online July 27, 2016. 9 Susan Schulten, professor, department of history, University of Denver (author of “Map Drawing, Graphic Literacy and Pedagogy in the Early Republic,” History of Education Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 2 [April 20, 2017], pp. 184–220), brought to our attention similar penmanship books by Frances Henshaw, 1823, at the Middlebury Female Academy (David Rumsey Map Collection, Stanford Library, Stanford University, California); and by Catharine Cook, 1818 (Osher Map Library, Southern Maine University, Smith Center for Cartographic Education, Portland) and Harriet Baker, 1819 (David Rumsey Map Collection), both at Mr. [Josiah] Dunham’s School Windsor, Vermont. 10 Jonathan Sarna, Boston-based Jewish historian and author of The Jews of Boston: Essays on the Occasion of the Centenary (1895–1995) of the Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston (Boston: Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston, 1995), in correspondence with the authors. 11 As seen in South-eastern View of Waterbury, an engraving by John Warner Barber, originally published in Barber, Connecticut Historical Collections (New Haven, CT: John W. Barber, 1836); illustrated in “Waterbury in the 18th Century,” fortunestory.org, accessed May 12, 2021.

NONIE GADSDEN is the MFA, Boston’s Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture.

TESS LUKEY is the MFA’s Luce Curatorial Research Associate.

SLOANE AWTREY is an independent scholar and former MFA Curatorial Research Associate.