Lush jungle vegetation, exotic animals, country folk, and a sultry tropical atmosphere are among the elements you might expect to find in paintings by one of Jamaica’s most revered artists of the first half of the twentieth century. Works by John Dunkley do indeed include many attributes of the luxuriant natural environment and rural social milieu of the colonial-era West Indies. But his imaginative landscape paintings and fetishistic carved wood and stone figures hardly aim merely to convey local Caribbean color.

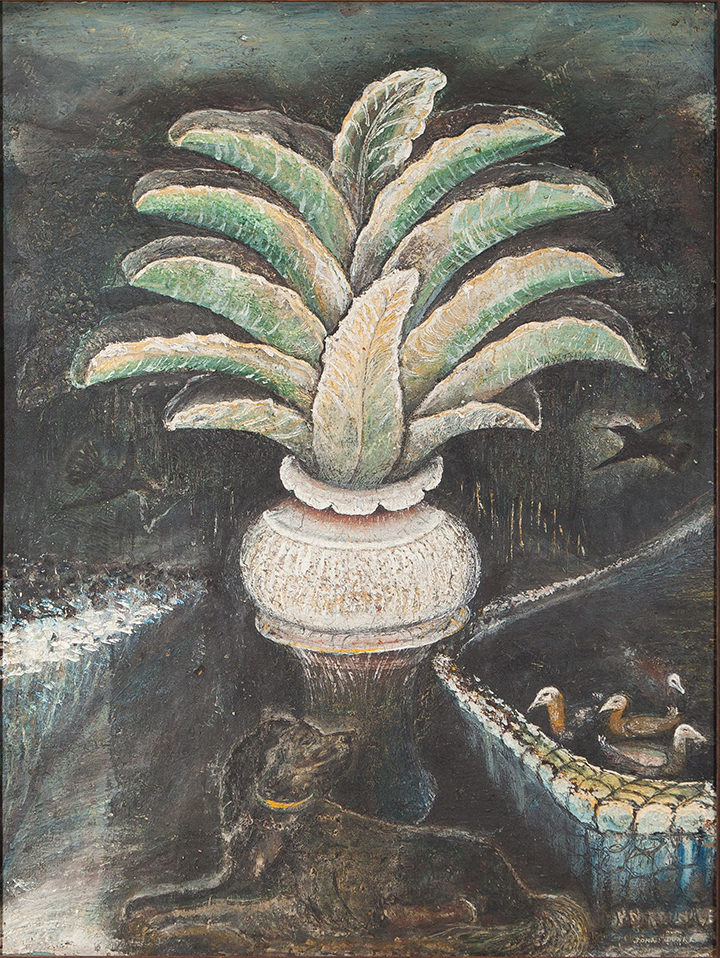

Fig. 1. Vase of Flowers by John Dunkley (1891–1947), date unknown. Mixed mediums on plywood, 22 1/4 by 16 1/4 inches. Collection of Wallace Campbell; all photographs courtesy of the Pérez Art Museum Miami.

Singular and esoteric, Dunkley’s visionary works are steeped in uncanny, ethereal light and harbor myriad references to the Bible, Afro-Caribbean mythic lore, and sociopolitical issues of his day. They also encompass a personal iconography frequently accentuated by quasi-surrealist touches and erotic overtones.

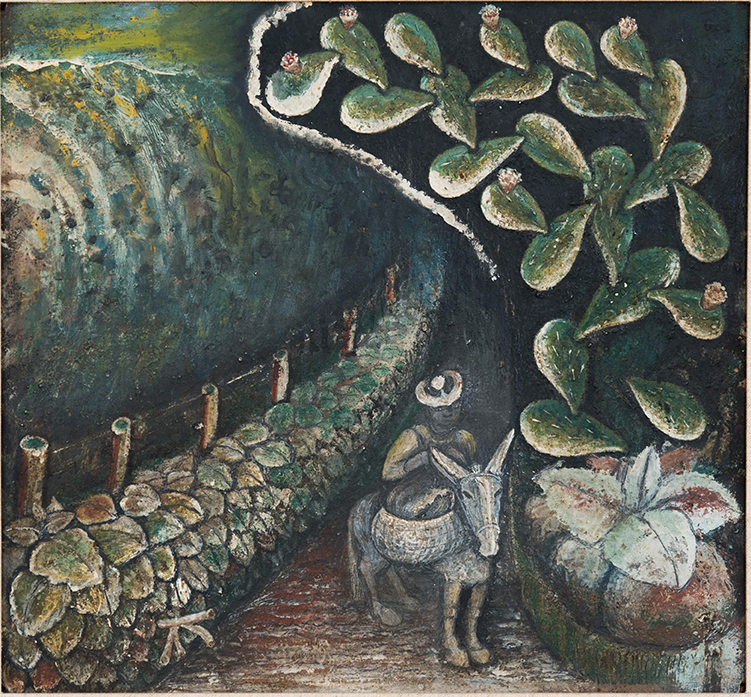

Fig. 2. Panama Scenery, date unknown. Mixed mediums on plywood, 26 1/2 by 32 1/2 inches. Collection of Michael Campbell.

Dunkley’s painting Banana Plantation (Fig. 6), for example, one of his best-known works, may be seen initially as a romantic, though schematically rendered, image of the tropics. A towering banana tree dominates the right portion of the vertical panel. The highly stylized tree glows against a pitch-black background, while a pattern of abstracted green-gray leaves meanders through other areas of the composition. A peculiar kind of illumination, however, contributes to the scene’s unfamiliar and rather eerie tone. A pale orange-yellow orb suggests a moon that bathes the plantation in a subdued and ghostly light. Evidence of some dubious nocturnal activities abound—a rabbit crouching in an elliptically shaped burrow nibbles a banana, while a crab scuttles along the ground nearby.

Fig. 3. Going to Market, date unknown. Mixed mediums on panel, 13 3⁄4 by 14 7/8 inches. Private collection.

This work, along with thirty-three other oil and mixed-medium paintings and thirteen sculptures by Dunkley, most making their US debut, recently featured in John Dunkley: Neither Day nor Night at the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM); the show is currently on view, in a slightly altered version, at the National Gallery of Jamaica, in Kingston. It represents a significant proportion of Dunkley’s entire output, since only about fifty of his paintings and even fewer sculptures survive, most produced in the last decade of his life. Organized by PAMM associate curator Diana Nawi, with Nicole Smythe-Johnson, an independent curator, the Miami event marked the first Dunkley solo exhibition in the United States. David Boxer, an artist, scholar, and former director and chief curator of the National Gallery of Jamaica, who died soon after the Miami exhibition opened, acted as curatorial adviser for the project. He also wrote much of the exhibition’s thorough and groundbreaking catalogue.

Fig. 5. Feeding the Fishes, c. 1940. Signed “JOHN DUNKLEY” at lower right. Mixed mediums on plywood, 16 3⁄4 by 20 1/8 inches. ONYX Foundation.

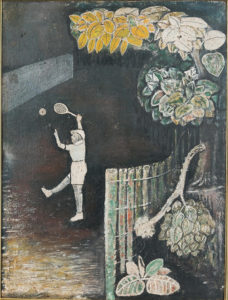

Fig. 4. Tennis Player, c. 1941. Mixed mediums on plywood, 16 7/8 by 13 inches. ONYX Foundation.

Dunkley’s biography—based on the meager information that has so far come to light—is extraordinary. Born in an impoverished area of rural southwestern Jamaica, he, like most of his countrymen of African descent, had few educational opportunities in a white-controlled British colony. The details of his early life are known mainly from a biographical essay, “The Life of John Dunkley,” written by his wife, Cassie, shortly after the artist’s death in 1947 from lung cancer at age fifty-six. The piece was published in the catalogue for a memorial exhibition presented by the Institute of Jamaica (IOJ) in Kingston in 1948.

In the last years of his life, Dunkley worked as a barber by day and an artist in his spare time, ensconced in a tiny studio behind the shop. In Kingston, where he lived and worked, there was almost no art community to lend support for his endeavor. And, like Jamaica itself, he was isolated from artistic developments elsewhere in the Caribbean. Nevertheless, Dunkley persisted in honing his skills as an artist. In his last years, he received a modicum of recognition, including his work’s appearance in several group exhibitions, though his fame is largely posthumous.

Fig. 6. Banana Plantation, c. 1945. Signed “JOHN DUNKLEY” at lower left. Mixed mediums on plywood, 29 1/8 by 17 5/8 inches. National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston, gift of Cassie Dunkley.

Jamaica was the last of the Greater Antilles territories to gain independence from a colonial power. While black nationalist movements like Garveyism, led by Jamaican-American activist Marcus Garvey (1887–1940), as well as Rastafarianism, fomented there for decades—from the late 1920s on—the country did not gain its independence from Britain until August 1962.

During Dunkley’s lifetime, segregation was rife, and educational and employment opportunities were scant for people of color. Like many of his unemployed and impoverished black countrymen, Dunkley sought work elsewhere in the Caribbean. Ostensibly, he spent time working in Cuba, and apparently for an extended period worked on a banana plantation in Panama.

According to Boxer, Dunkley cannot be accurately categorized as an “outsider,” “folk,” or “self-taught” artist. Instead, he uses the term “intuitive” when describing Dunkley and other Jamaican artists working outside academic and formal art institutions. Undated sculptures by Dunkley—Mule with Dray (made of carved cassia and horn) and the wood carving Market Woman Selling Pumpkin—with their distorted proportions and sentimental imagery, might seem like eccentric and enchanting whittlings of a local artisan appealing to the tourist trade. His endeavor, however, is multifaceted, enriched by art historical references—including to African art—as social commentary, and Dunkley’s profound ambition.

Fig. 7. Most Faithful, c. 1939. Signed “JOHN DUNKLEY” at lower right. Mixed mediums on plywood, 24 1/8 by 18 1/8 inches. ONYX Foundation.

There is evidence that Dunkley trained at some point as a photographer. There are also accounts that he spent considerable time in the library of the IOJ, a study center for art and science that was founded in 1879, where he would have perused the art books that were major sources of inspiration for him. Stories in local newspapers, especially the Daily Gleaner, and glossy magazines such as Life also provided him with ideas. Boxer proposes that Dunkley was directly influenced by Salvador Dalí’s Persistence of Memory (1931) and works by other surrealists reproduced in a Life article covering the Museum of Modern Art’s 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism.

Dunkley adopted the infinite perspectives and disconcerting imagery associated with surrealism. He added prominent spiderwebs and strange animals to his otherwise bucolic pastoral scenes, as in Spider’s Web (Fig. 9) and Scene with Path. His exposure to surrealism may also have inspired his anthropomorphized landscapes and the coded sexual fantasy found in many of his works. Certain paintings, such as Feeding the Fishes (Fig. 5), with its phallic tree trunk and hillside crevices suggestive of female genitalia, lend themselves to a Freudian psychosexual interpretation, as do many works of surrealism.

Fig. 8. The Kangaroo, date unknown. Cedar; height 12, width 6 3⁄4, depth 1 3⁄4 inches. Collection of Wallace Campbell.

The jerboa, a miniature kangaroo-like creature native to Africa, was of particular fascination for him, likely after an article about it appeared in the Daily Gleaner in 1940. The jerboa, incidentally, was used as a logo for British army divisions stationed in North Africa in World War II— the so-called Desert Rats. Dunkley features the animal in a number of works, including the painting Jerboa, and a related woodcarving The Kangaroo (Fig. 8), whose highly polished schematic form corresponds to depictions of animals in West African sculpture. Certain art books in the IOJ library appear to have been of particular fascination for Dunkley, especially monographs on Henri Rousseau and William Blake. The stylized leaves and other vegetation in a number of Dunkley’s paintings, including Going to Market (Fig. 3), Woodland, and Most Faithful (Fig. 7), are akin to the otherworldly verdure of Rousseau’s famous jungle pictures.

Dunkley’s compositions likewise echo the rigorous symmetry, ambiguous perspectives, and other spatial devices Blake frequently used. Also evident in Dunkley’s work are the compressed spaces and celestial light found in the mystical landscapes by British romantic painters such as Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), and even in works by neo-romantic near contemporaries of Dunkley’s, such as Graham Sutherland (1903–1980), whose dense and sinuous landscape drawings and etchings of the 1920s and ’30s have a great deal in common with the Jamaican artist’s work.

Dunkley’s painting Tennis Player (Fig. 4) shares the stylized figuration and considerable charm of Rousseau’s well-known 1908 sporting image, The Football Players, now in the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Oddly, Dunkley’s image shows a lone white tennis player on the left, about to hit the ball to an unseen opponent across the net, the other side of the court being incongruously obscured. According to Boxer’s interpretation, Dunkley makes a wry comment in this work about tennis as an elitist sport in Jamaica at the time. In the 1930s and ’40s, while blacks were not allowed on most courts, the career of a white tennis luminary, George Dunkley—possibly the painting’s subject—was often reported in the newspapers. In Dunkley’s visual code, the invisible player likely alludes to the discouraging absence of black players on Jamaica’s tennis courts.

Fig. 9. Spider’s Web, date unknown. Signed “JOHN DUNLEY” at lower right. Mixed mediums on canvas, 17 1/8 by 28 3⁄4 inches. Collection of Ernest, Kenneth J., and Tina Dunkley.

One of Jamaica’s biggest news stories of the period occurred in 1940, near the start of World War II, when the United States acquired from Great Britain some twenty thousand acres in southern Jamaica to be used as a naval base. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s visit to the island to inspect the site was a major event. Dunkley commemorated the visit in President Roosevelt Gazed at Portland Bight, which shows Roosevelt’s head, looming as large as a billboard in the middle of a tropical landscape, the sea visible in the distance.

The naval base was intensely controversial, as the project called for the displacement of many local residents, mostly poor black farmers. Dunkley refers to their plight in Sandy Gully, a woodcarving named after one of the displaced villages. The sculpture shows the seated figure of a black man whose limbs are taut with anxiety, and whose face is full of consternation, fear, and anger. It is a moving image, redolent of Dunkley’s range of expression, and his command of emotional impact.

Dunkley’s work offers much more to be explored and learned. A master of Jamaican vernacular, his unique work encompasses a profound examination of personal and cultural identity. His vision, bathed in the hushed tones of a Caribbean twilight, imparts a universal message, ultimately one of hope. Graceful and elegiac, his art is long overdue for international attention.