No American artist is better known to his countrymen than Winslow Homer. What Mark Twain is to fiction and Walt Whitman is to poetry, Homer, at least in the popular imagination, is to painting. “America’s greatest and most national painter,” Earl A. Powel III, the former director of the National Gallery, called him a generation ago, a somewhat facile phrase that, with insignificant variations , has been repeated a thousand times. Indeed, Homer is so familiar to us that his very fame stands between us and his art: because we so energetically esteem him, we no longer feel that we need to look at him. Fortunately, a new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents, curated by Stephanie Herdrich and Sylvia Yount, provides an excellent occasion to re-examine his work. Featuring ninety oil paintings and watercolors, it is the largest Homer exhibition, though hardly the only one, to be staged in the past quarter century.

The first thing we’re likely to learn from looking at all of these works is that Homer was not the man we thought he was. Even though The Veteran in a New Field (Fig. 2), and Snap the Whip, 1872, portray Americans at their labors and their leisure, Homer never partook of his subjects’ energy or spirit of play, nor did he observe them with much sympathy or, for that matter, antipathy. In general, we Americans expect our cultural figures to exuberate, as Whitman and Twain did, each in his own way. A century later, Pollock and Rauschenberg exuberated as well, and it is that exuberance that makes them seem, for all their vanguardism, essentially American in ways in which Ad Reinhardt and Jasper Johns do not. For all the robustness of his outdoor scenes, Homer had the soul of a Scandinavian artist—someone like Vilhelm Hammershøi—living a cloistered life of radical interiority, moving amid the shadows and muffled silence of little rooms. A shy man who never married and had few friends, he seems never to have let anyone in, and, more importantly, never to have let himself out. When William Howe Downes inquired about writing his biography, Homer’s reply was swift and inexorable: “It would probably kill me to have such [a] thing appear. . . . The most interesting part of my life is of no concern to the public.”

And while Homer traveled an impressive amount— to France in the 1860s, to England and the Bahamas in the 1880s—he never became, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, “a part of all that I have met.” Had he simply stayed home, he would not have acquired the hard visual data that, as a committed realist, he needed, but in purely affective terms it would have made little difference. Arriving in Paris at one of the watershed moments in the history of art, he does not appear to have interacted with any of the locals, let alone to have experienced, along with his fellow expatriates, anything of the legendary vie de boheme that famously flourished in those years. As one historian put it, “What he thought of all that he saw there he never shared with anybody.”

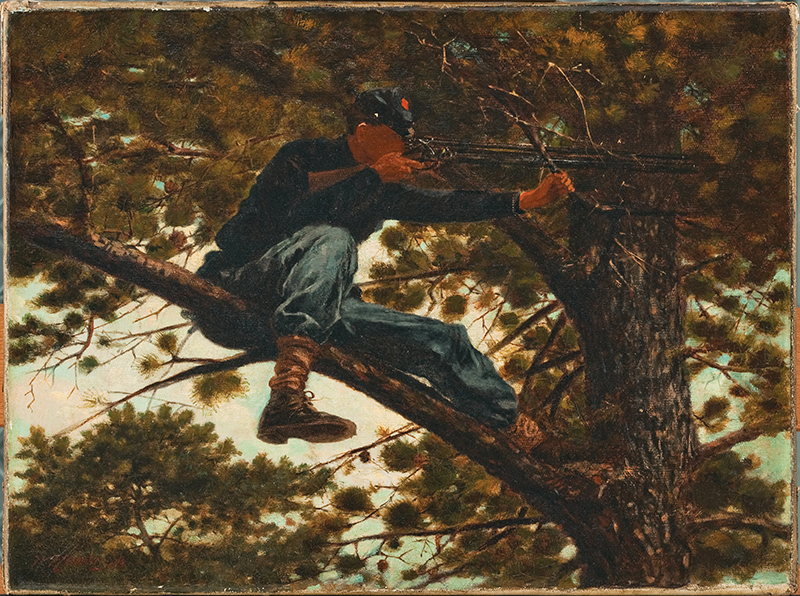

It takes a practiced eye, perhaps, to perceive that radical restraint in the context of the images—some of them icons of American art—that fill the galleries at the Met. But it is there, in varying forms, from the beginning of Homer’s career to the very end. Born in Boston into a fairly well-to-do family, he grew up in nearby Cambridge and soon after graduating from high school he found gainful employment as an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly and Ballou’s Pictorial. In 1859, at the age of twenty-three, he moved to New York, where he took a few courses at the National Academy of Design. But it was only during the Civil War, after Harper’s had sent him to the front lines as an illustrator, that Homer came into his own as a serious painter. Sharpshooter (Fig. 3), one of his most famous works, depicts a Union soldier sitting in a tree, his rifle trained on some distant and unseen target. So neutral is the treatment that one is surprised to read Homer’s assessment of the depicted action as being “as near to murder as anything I ever could think of in connection with the army.”

The affectless neutrality of that painting would endure, largely unaltered, to the end of his career: it is the essence of Homer’s art, even in such slightly looser watercolors as After the Hurricane, Bahamas, which he painted toward the end of his life (Fig. 7). Well before he reached Paris in 1866, Homer had seen the realist works of Courbet and his followers in the galleries of Boston and New York, and his fealty to the movement would never waver. But to be a realist implied certain things, above all a disabused servitude to the observable world and a refusal to engage with it in any emotional way. Impressionism, for which Homer never had any use, emerged out of realism, but it represented, as Émile Zola famously claimed, “a corner of creation viewed through a temperament.” Homer constantly and skillfully portrays the drama and passion and movements of men, but he stands at the frigid periphery of human life, an observer who will have no part in it all. Breezing Up (A Fair Wind) completed in 1876, depicts a father and his three sons sailing through churning, sunlit waters (Fig. 4). But as in so many of Homer’s depictions of water, that most fluid of elements, he has conjured it into a state of concretized stillness, as his human actors gaze, without speech or gesture, upon the open sea.

Fig. 7. After the Hurricane, Bahamas, 1899. Signed and dated “HOMER 99” at lower left. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper, 14 5/8 by 21 3/8 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection.

Perhaps his most monumental work, Dressing for the Carnival from one year later, is also his most boldly chromatic painting (Fig. 1). In this depiction of a family of the freed enslaved, two women help a man into a garment of brilliant golds and deep reds, while a group of children look on. Contemporary depictions of Black life, by such artists as Edwin Forbes and Eastman Johnson, strove to awaken an element of charm and anecdote. Homer, however, allowed himself no such endearments. By design he refuses to pierce the surface of the observable world. The joyous pomp of the painting is registered, but it is not felt and it is not conveyed to the viewer.

Fig. 9. The Gulf Stream, 1899. Signed and dated “HOMER/ 1899” and inscribed (partly painted over) “At 12 feet you can see it” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 by 49 1/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection,Wolfe Fund.

Through a kind of democratic leveling, Homer’s depictions of white men and women are, in this respect, no different. Consider Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts (High Tide), in which three women dry out on a beach, while a dog barks at them (Fig. 5). This image, with its hint of bare legs, would seem to promise, at the very least, some sort of erotic charge. But none is forthcoming, even though the painting still awakened the indignation of certain bluenoses. When a similar response greeted his Promenade on the Beach, and he was asked to account for his work, he responded sarcastically that, “The Girls are ‘somebody in particular,’ and I can vouch for their good moral character. They are looking at anything that you may wish to have them look at . . . [some] appropriate object for Girls to be interested in.”

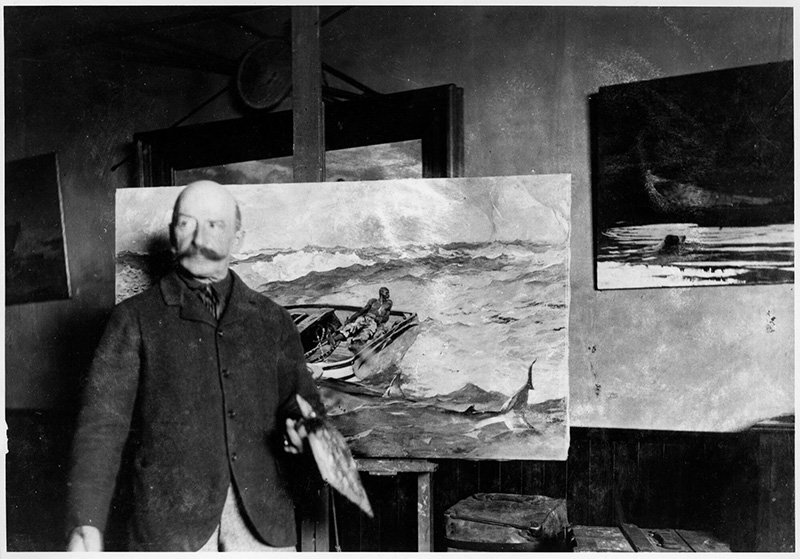

This response underscored Homer’s impatience with humbug, but even more, his positive loathing for having to describe and explain any element of his art. One of his best-known works, The Gulf Stream in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, depicts a Black man in a boat with a broken mast adrift on the open seas, surrounded by sharks (Fig. 9). Few works by Homer would seem as fraught with anecdote as this, and so it provoked endless speculation that has persisted to this day. “I regret very much that I have painted a picture that requires any description,” Homer wrote, in response to the urgent queries of his public. “You can tell these [inquisitive schoolma’ams] that the unfortunate negro who now is so dazed & parboiled, will be rescued & returned to his friends and home, & ever after live happily.” This almost polemical abhorrence of commentary, this thorough rejection of thematic interpretation, creates an odd friction between the curators of the present exhibition and their chosen artist. Current museological practice has increasingly rejected chronological and formalist narrative in favor of thematic interpretation, and few recent exhibitions have gone as far in this direction as the present show. “Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents examines the canonical chronicler of nineteenth century America through the lens of conflict,” Sylvia Yount writes in the catalogue introduction, citing “the fascinating ambiguities and contradictions of the artist’s work.” By conflict, she means that which arises among classes and races, among other things: “More Homer scholarship needs to critically interrogate how race and class and their structures of power weave throughout his production.” The result is an exhibition of Winslow Homer that is, if not for the ages, very much for this age.

Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from April 11 to July 31.

The Homer quotes in this article are from the accompanying catalogue by Stephanie L. Herdrich and Sylvia Yount published by the Metropolitan Museum.