In the late nineteenth century, when the colorful and glossy earthenware called majolica was at the height of its popularity, ceramics factory floors teemed in Britain and America. Entrepreneurial owners made fortunes as staff artisans pummeled, sliced, squeezed, and sculpted slabs of clay. Glazes for multiple kiln firings were concocted from antimony, arsenic, manganese, and lead. Buyers of almost every socioeconomic stratum could afford the results of the gritty, arduous manufacturing process.

Whimsical and astounding creations emerged from the kilns. Along the rims and handles of teapots and vases, monkeys squabbled, sailors sprouted three legs, and deities performed contortionist backbends. Miniature boots, hats, rowboats, lighthouses, and beehives held matches, ink, ferns, toothpicks, and food. Serving pieces and flowerpots also depicted various organisms in mid-decay. Vessels “disguised the dribbling contents of a game pie in a tureen topped with lifelike duck and hare heads, hid a tangle of roots and soil in a planter seemingly woven from sticks and leaves, or preserved smelly Stilton in a cheese dish besieged by mice,” Jo Briggs, a curator at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, writes in a new book, Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915.

The three-volume, juicily detailed tome accompanies an exhibition to be presented next year, first at the Bard Graduate Center in New York, and later at the Walters. Dozens of scholars have collaborated to shed light on products that are fervently collected in some circles, and elsewhere maligned as kitsch. Majolica’s innovative designers synthesized imagery from influences as disparate as Japanese Noh masks, Egyptian canopic jars, Darwinian science, and baseball.

Susan Weber, the Bard Graduate Center’s founder, grew intrigued with majolica years ago partly because “it elicited such strong reactions from people.” The BGC curatorial team has acquired majolica objects by the dozens to scrutinize clay bodies, glazes, and markings. “Every day, the boxes from eBay and Etsy were coming in,” Weber says. And as more insights surfaced about forgotten companies and their context, she adds, the catalogue “could have been five volumes, frankly.”

The first generation of makers, in 1840s Britain, drew inspiration from Renaissance tin-glazed maiolica that was entering the collections of royals, aristocrats, and newly established museums. The companies brought in French experts, most notably a Sèvres veteran named Léon Arnoux (1816–1902), to expand design repertoires and palettes. By the 1850s the variant spelling majolica had been popularized by ceramics tycoon Herbert Minton (1793–1858). Imitators in the neighborhood of his Staffordshire factory soon flooded the market. The variety of forms in high-keyed hues “seemed to epitomize Victorian Britain’s industrial prowess, its confidence in its science and engineering, and its optimism,” Weber writes in the new book.

The industrialists and buyers must have also felt some nostalgia for the British countryside that was vanishing as the factories grew. Objects were molded with shepherdesses, wheat sheaves, brambles, cowslips, and “cottages with flowering ivy above their doorways,” Weber writes. Colonial ambitions were expressed in the clay, too, in the form of motifs of tropical flora and—appallingly—enslaved Africans, whose figures were incorporated into objects as various as candleholders and garden seats.

British tastemakers promoted majolica housewares at every scale, from fountains, gasoliers, and umbrella stands to menu holders, spoon warmers, sardine boxes, and cuspidors. Windsor Castle’s Royal Dairy is stocked with majolica statues of tritons and nymphs, and bas reliefs of infant farmers at work and play. “Some are dancing around a maypole, some are ploughing with goats, while others are gathering flowers, catching butterflies, reaping wheat, harvesting grapes, pulling carts, and ice-skating,” Julius Bryant, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s keeper of word and image, writes in the catalogue. Majolica carousers can be found along the V&A walls as well, he notes: “some revelers are banging on drums, clashing cymbals, or rolling barrels, while others are drinking from bottles in baskets, brawling, and carrying off their drunken friends.”

Factory founders and employees, by contrast, had little time for frivolities. Many came from families that had made pots for generations. No one expected them to stay in school. By age sixteen, Herbert Minton was already on the road, “responsible for presenting the pottery’s new lines to its important wholesale and retail customers, listening to their requirements for new forms and decoration, and then taking their orders back to the factory,” Miranda Goodby, the senior curator of ceramics at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent, writes in the catalogue. Maintaining livelihoods was a precarious task; manufacturing plants were at constant risk of devastating fires, and competitors’ plagiarisms led to costly lawsuits.

Goodby also contributed a macabre chapter titled “The Fearful Malady of the Clay.” It details how toxic fumes shortened ceramists’ lives and how reformers struggled for decades to impose safety regulations. For the exhibition, contemporary artist Walter McConnell has stacked grayish ceramic shards to form a stupa, commemorating the sufferings that made the product lines possible.

In search of better workplace conditions, droves of Staffordshire makers resettled in the United States. They ignored Josiah Wedgwood’s warnings, cited in the catalogue, that homesickness would leave immigrants with “a disease of the mind, peculiar to people in a strange land . . . an unspeakable longing after their native country.” New companies were scattered from Peekskill, New York, to Baltimore and St. Louis. Freshly Americanized designers devised brand names as exotic as Venicene and Scarabronze and as enigmatic as Tenuous Majolica. Since the new facilities were often set up on town outskirts, the laborers had access to a little more fresh air than was available to their British counterparts. But that did not mean young people were protected from hazards. The catalogue quotes one observer at a plant in East Liverpool, Ohio, who noted in 1878, “Little boys are trotting along with lumps of clay as large as themselves.”

By 1900 or so, American and British manufacturers were scrambling to adapt to the public’s growing taste for more subdued “art pottery” that was billed as unique and not mass-manufactured. The V&A formed an ominous-sounding “Disposals Board for Ceramics” that handled the offloading of mid-nineteenth-century majolica, even pieces that had been lauded at world’s fairs.

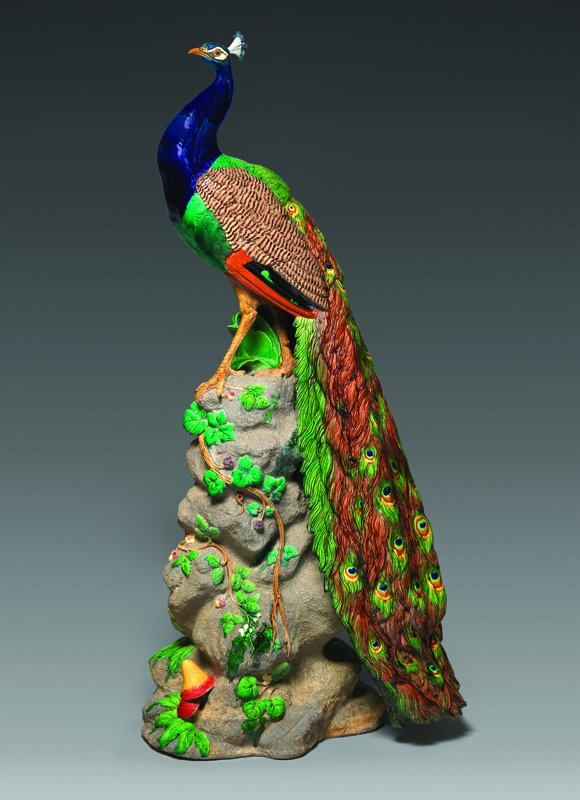

Among scholars, collectors, and dealers, majolica largely gathered dust in storage until a revival of interest in Victoriana in the 1960s and ’70s. “Majolica Makes a Bold Comeback” was the New York Times’s headline for Rita Reif’s review, published on April 4, 1982, of a British majolica survey at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York. She cited “an exuberance and technical virtuosity that are hallmarks of a period which has been thought of, wrongly, as stodgy and lacking in imagination” and expressed hopes for “a comprehensive majolica show” in the future. Only in the last decade, however, has momentum built in the niche field. In 2014–2015’s Sculpture Victorious, a traveling exhibition about Victorian sculpture, Minton’s depictions of a peacock and elephant towered over museumgoers. In the recent redo of the British galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Minton’s contributions include a fan-shaped “Persian” bottle in cornflower blue.

Earlier this year, majolica from the estate of the late interior designer Mario Buatta brought many multiples of their auction estimates in sales at Sotheby’s and at Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York. Buatta had amassed, for instance, Wedgwood scallop-shell compotes with snail-shaped feet and Staffordshire vases in the form of elephants bearing honey-colored crenelated castles atop their pink-fringed saddles.

Among the highlights of Majolica Mania are a Minton peacock and a turquoise vase about four feet tall, covered in figures of snakes and enchained Roman warriors (on the lid, an eagle pecks at Prometheus’s liver). Less perturbing is a Wedgwood jug, sculpted with cricketers and soccer players, alongside its American knockoff portraying baseball players made in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, by Griffen, Smith, and Co. Weber notes in the catalogue that in the 1880s, Griffen executives “sponsored two baseball teams: the Etruscans, made up of nine clay workers, and the Common Heights, composed of men who worked in the kilns.” Those laborers must have been amused to see athletes in ballgame uniforms molded in majolica as they left their stuffy workplaces and headed out to their own playing fields in the fresh air.

On view: Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York (September 24, 2021–January 2, 2022 and now as an online exhibition) and Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (February 26–July 31, 2022).