George Biddle wasn’t having it. “No more Hellenic nudes representing the spirit of American Motherhood, Purity, Democracy and the Pioneer Spirit,” he declaimed in the March 1934 issue of Scribner’s Magazine.1 Hailing the nascent back-to-work mural program of the Franklin Roosevelt administration, he called for robust, realist paeans to agriculture and industry, education and invention—the whole gamut of muscular American life in the twentieth century. A well-born Philadelphian whose surname is synonymous with success and civic engagement in Pennsylvania and beyond, Biddle practiced what he preached. Committed to representation, his own work was informed by a Deweyesque sense of art as a purposeful, moral experience more than as a product or purely creative gesture. With George Biddle: The Art of American Social Conscience, Philadelphia’s Woodmere Art Museum explores the career and motivating philosophy of a native son whose name is less familiar than it was, but who was very much a part of one of the more singular (albeit brief ) eras in American art.

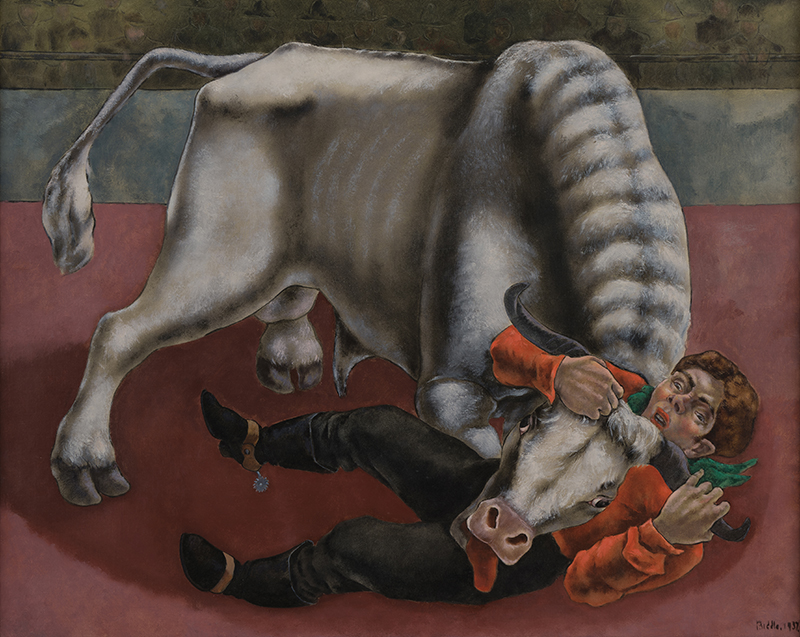

Fig. 2. Prosit, 1933. Signed and dated “Biddle 1933” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 8 7/8 by 11 7/8 inches.

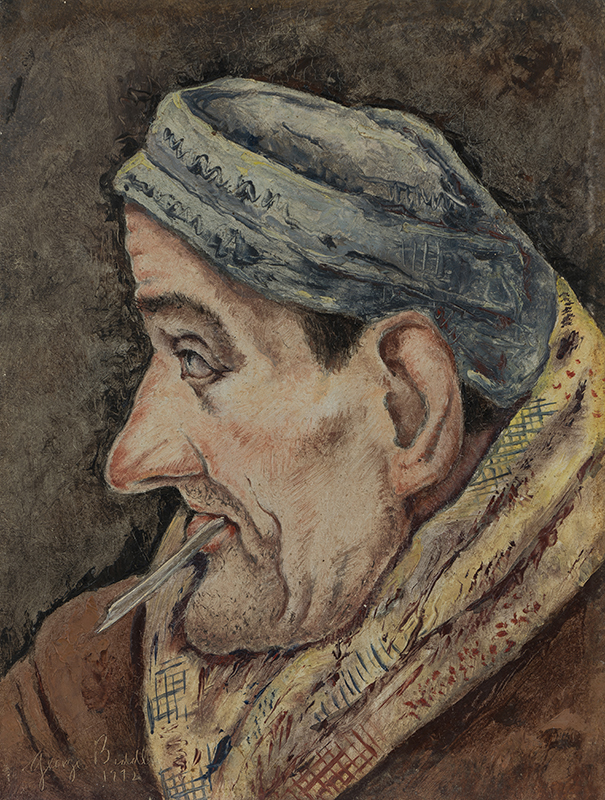

Fig. 3. In a Brazilian Lunatic Asylum, 1942. Signed and dated “George Biddle/ 1942” at lower left. Oil on panel, 11 ¾ by 8 7/8 inches.

As comfortable and well-connected as he was (Mary Cassatt took him in hand when he arrived in Paris after Harvard Law School to study at the Académie Julian), Biddle was very much a working artist. He pursued various mediums—becoming a masterful etcher, lithographer, and woodcut artist—enjoyed solo exhibitions in New York and elsewhere, and was included in group shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and elsewhere. George and Ira Gershwin commissioned him to illustrate the libretto for Porgy and Bess and he created a mural for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. His work may not have received the level of attention enjoyed by some of his contemporaries, but his career was defined as much by what he said and did outside the studio as it was by an oeuvre.

Biddle published several books, including an autobiography, and contributed articles to various publications, including a lengthy piece for the December 1947 issue of The Atlantic entitled “Modern Art and Muddled Thinking.” (For Biddle, analyzing the schism between the traditional and the progressive was an idée fixe.) In 1943 he was appointed chairman of the US War Artists Committee. Biddle not only selected the artists to document the theaters of war but spent six months himself with troops in Tunisia. In 1950 President Harry Truman appointed him to a four-year term on the Fine Arts Commission, which had been established by Congress in 1910.

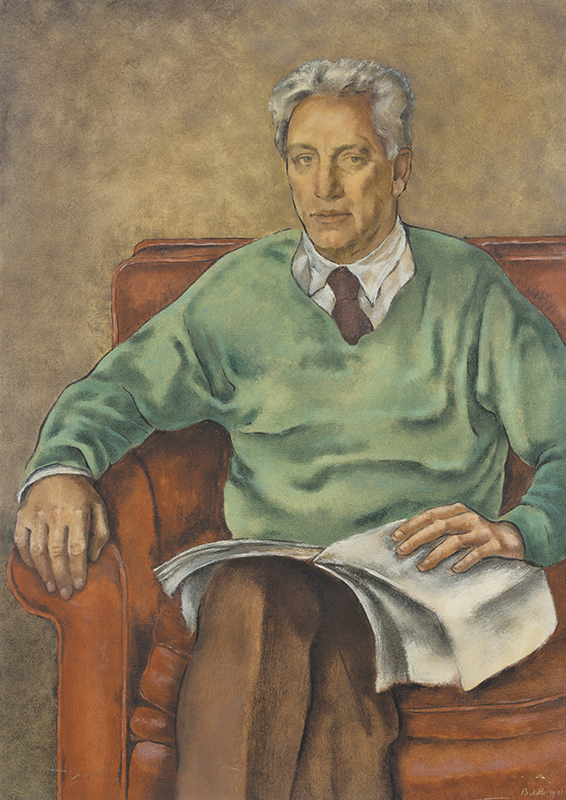

Fig. 5. Max Eastman [1883–1969] , 1937. Signed and dated “Biddle 1937” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 35 by 25 inches.

Fig. 7. Mother Dressing Daughter, 1917. Initialed “B” at upper left and inscribed “17” at upper right. Handcolored etching, 6 3/4 by 5 7/8 inches. Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia, gift of the Michael Biddle Family.

Biddle’s most significant Washington association began in 1933, when he wrote a letter to his Groton and Harvard classmate Franklin D. Roosevelt, extolling the work of Diego Rivera and other Mexican muralists who had received the support of the Obregón government in the 1920s. Biddle saw in that post-revolutionary project a parallel in the US as the country slogged through the Depression. “The younger artists of America are conscious as they have never been of the social revolution that our country and civilization are going through and they would be eager to express these ideals in a permanent form if they were given the government cooperation.”2

Roosevelt put Biddle in touch with Treasury Department official Lawrence Robert. Robert, in turn, introduced Biddle to his colleague Edward Bruce (a lawyer/artist like Biddle), and the two devised a plan to get artists working. In December of 1933, seven months after Biddle’s missive to FDR, relief czar Harry Hopkins announced the formation of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). With a budget of $1,034,754, it got artists creating not only murals, but easel paintings, sculpture, and prints; weekly wages ranged from roughly $38 to $46. Although short-lived (concerned about the expense, Roosevelt terminated the program in 1934), it paved the way for the Federal Art Project and the multi-disciplinary initiatives of the Works Progress (later Projects) Administration.

Biddle’s fascination with the Mexican muralists, and Rivera in particular, stemmed, in part, from a lengthy visit with the latter in 1928. By the time Biddle wrote his letter to the president five years later, Rivera had already worked in the US executing murals for the Pacific Stock Exchange Building in San Francisco and the Detroit Industry panels at the Detroit Institute of Arts. His unfinished fresco for what was then known as the RCA Building in New York was destroyed when the Rockefellers took offense at a depiction of Lenin in the piece. While hardly a radical, Biddle came in for his share of criticism when creating public works. His Society Freed through Justice, one of a number of murals commissioned for the Department of Justice building in Washington, earned admiring coverage in the New Yorker, but conservatives at the Fine Arts Commission deemed his style “somewhat French and very Mexican . . . intrinsically un-American and ill-adapted to express American ideas and ideals.”3 The five-panel piece contrasts tenements, sweatshops, and idle factories with citizens living lives elevated by a just socioeconomic system.

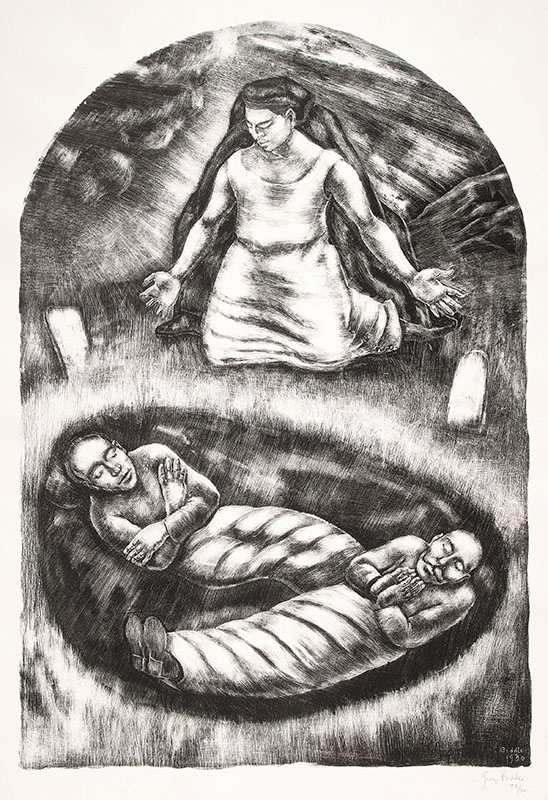

Fig. 9. Sacco and Vanzetti, 1930. Signed and dated “Biddle/ 1930” at lower right of the print, and “George Biddle/ 48/50” on the border below. Lithograph, 23 by 16 inches. Woodmere Art Museum, gift of Jim’s of Lambertville, New Jersey.

Fig. 10. Helene Sardeau, 1934. Signed and dated “Biddle.1934” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 40 by 30 inches.

Biddle articulated his fervent attachment to murals in his 1934 Scribner’s article, “An Art Renascence Under Federal Patronage.” Mural painting, he asserted, “is collective and social, rather than aristocratic and individual. And it is further obvious that the more collective and social is the nature of the building the more readily it adapts itself to noble, universal themes for mural work.”4 How this son of privilege came to understand art as a function of an egalitarian society is not easily determined, but Woodmere CEO William Valerio, who organized the Biddle exhibition, suggests various factors that may have formed his outlook. “Biddle’s education at the Academy of the Fine Arts was in realism, studying under Thomas Anshutz through a curriculum developed by Thomas Eakins. And his experience in World War II, where, because of his language skills, he interrogated German prisoners, had a longstanding effect on him. We know that later, while living in Tahiti, he read Clive Bell’s Art, but Bell’s ideas did not correspond to his life experience, either in terms of his training or his experience in the war.”

Fig. 11. German Prisoners, 1943. Signed and dated “George Biddle/ 1943” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 10 by 14 inches. Michael Biddle Family collection, promised gift to the Woodmere Art Museum.

Fig. 13. Indian Village Scene, 1960. Signed and dated “Biddle 1960” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 25 by 30 inches. Woodmere Art Museum.

While readily admitting that enervating academicism can undo artists of any stripe, Biddle thought the best hope for intelligible, communicative power lay in the figure and representation. Writing in the New York Times in 1946, he stated, “I think much of modernism is far more concerned with artistry than life; that it frequently gives us pleasure and almost never moves us deeply… that its roots are not fed from passion or love or tears; that it will never sweep us to any great heights.”5

Although Biddle’s early work manifested a Cassatt-like nicety (Fig. 7) and his Tahitian sojourn changed his use of color and prompted him to paint exuberant depictions of vegetation, the determination to be meaningful, to project a narrative, to comment was not long in coming. His encounter with the Mexican muralists in the 1920s confirmed his philosophy that art is an act of intellectual and emotional engagement. The simultaneous exaggeration and simplification that characterized the work of many Mexican muralists influenced Biddle’s own paintings, such as his 1930 homage to executed anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti (Fig. 9) and The Harvest, South Carolina (Fig. 8). But not all of his work manifested that influence. Hired by Look magazine to cover the Nuremberg trials (his brother Francis was one of the judges), he sketched straightforward renderings of the prosecuted and the prosecuting. And there’s a Daumier-meets-George Grosz aspect to the oil portrait Prosit (Fig. 2), in which a fat-fingered man raises a glass to his pursed lips, and in the seemingly quizzical profile of the patient in In a Brazilian Lunatic Asylum (Fig. 3).

Always a great traveler, in the late 1950s, Biddle visited Japan, Southeast Asia, and India (Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru sat for a portrait) accompanied by his third wife, sculptor Hélène Sardeau (1899–1969). The two, years earlier, worked on joint artistic projects in Mexico City and Rio de Janeiro. He continued to make art well into the 1960s, producing dozens of oils and lithographs (Fig. 6). There were solo shows in New York and Provincetown, Massachusetts, and, in 1961, he was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters. (Sculptor Jacques Lipchitz and architect Ludwig Mies van de Rohe were also among the honorees that year.) Several years before his death in 1973, at age eighty-eight, Biddle wrote: “I was given a good education. Some talent. Enough success. This has given me a lasting sense of obligation to leave the world a little better, those who come after me a little happier, to have wasted no opportunities.”6

George Biddle: The Art of American Social Conscience will be on view at the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia from September 24 to January 22, 2023.

1 George Biddle, “An Art Renascence Under Federal Patronage,” Scribner’s Magazine, vol. 95, no. 3 (March 1934), p. 430. 2 George Biddle, An American Artist’s Story (Boston: Little, Brown, 1939), p. 268. 3 Ibid., p. 185. 4 Biddle, “An Art Renascence Under Federal Patronage,” p. 429. 5 George Biddle, “The Artist on the Horns of a Dilemma,” New York Times, May 19, 1945, p. 44. 6 Biddle journal entry dated January 14, 1962, George Biddle papers, circa 1910–1970, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

THOMAS CONNORS is an arts writer based in Chicago.