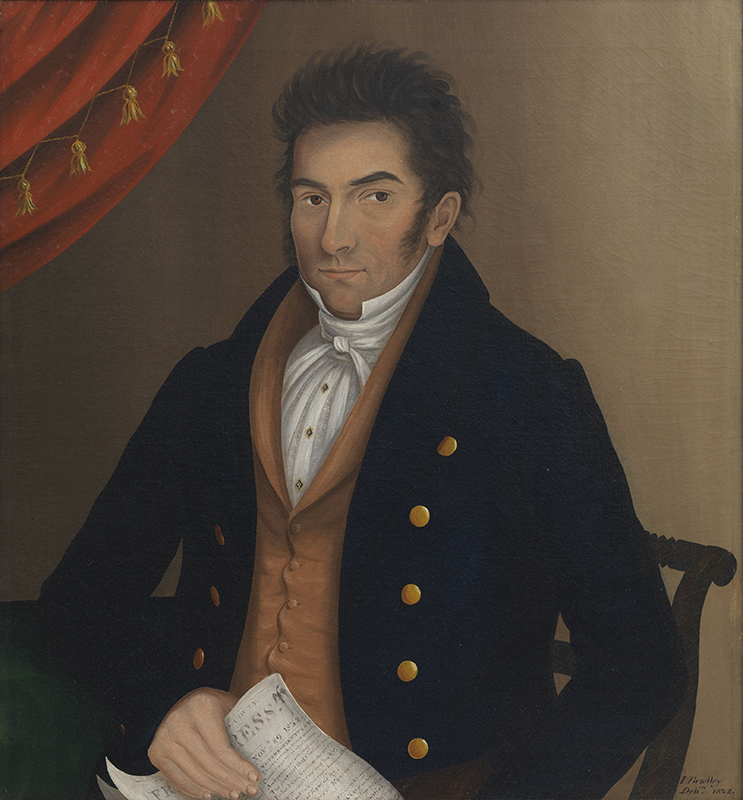

Fig. 1. Asher Androvette by John Bradley (active 1832–1845), 1832. Signed and dated “I Bradley Deli.n 1832.” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 28 5/8 by 26 1/4 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Peter and Jeffrey Tillou.

In the popular imagination, works of American folk art from centuries past are rural creations—from figurines carved by farmers in their idle hours, to naive portraits painted by artists who roamed from village to village— and, too often, exhibitions foster that perception. In fact, much of what we consider folk art was produced in cities, and could have been produced only amid dense populations, where businesses and a burgeoning merchant class placed a premium on artisanal and artistic talents. New York City was particularly fertile ground in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for those with creative abilities: it was a growing center of trade and the manufacture of everything from furniture to ships, with access to abundant natural resources, and a constant need for skilled labor. A key factor in the prosperity of New York City, visible in the folk art produced there, was its attitude toward immigrants. Not all newcomers were welcome and not every family’s story ended in success, but a steady stream of immigrants gave the city a continuously growing population of consumers and, more important, a flood of diverse talents and cultural traditions.

A new exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum—and an accompanying book—examines the relationship in New York’s past between folk art and the business world, as both a wellspring of artisanal production and as the subject of works of art. Both book and exhibition explore a range of creative genres, and the objects and artworks on view tell the stories of an array of talented, and often colorful, artists and artisans of old New York.

Fig. 2. Punch bowl attributed to John Crolius Jr. (1755–c. 1835), 1811. Inscribed “Elisabeth Crane May 22th 1811” below rim. Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt decoration; height 7 3/4, diameter 15 1/2 inches. American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian; photograph by John Bigelow Taylor.

Many sites in the city bore deposits of clay suitable for making redware and stoneware. Among the best-known stoneware makers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were Johan Willem (John William) Crolius, who arrived in Manhattan from Nieuw Wit (Coblenz), Germany, in 1718, and his descendants and extended family. An elegant stoneware punch bowl (Fig. 2) has been attributed to the pottery owned by grandson John Crolius Jr. The bowl is thinner and more elegantly shaped and delicately decorated than most contemporaneous American stoneware. Its form, with a raised straight foot and rounded flaring wall, was probably copied from examples of Chinese export porcelain. The incised pattern of vines and blossoms has been likened to designs on eighteenth-century delftware and textiles. The inscription on the bowl, which reads “Elisabeth Crane May 22th 1811,” indicates that it was possibly a marriage or anniversary gift to a member of the Crane family of Cranetown (now Montclair), New Jersey. It has recently been suggested that the bowl may have been made by Caleb Crane, a potter in the Crolius workshop, as a gift for his wife Elisabeth, or as a christening bowl for his daughter, also named Elisabeth.1

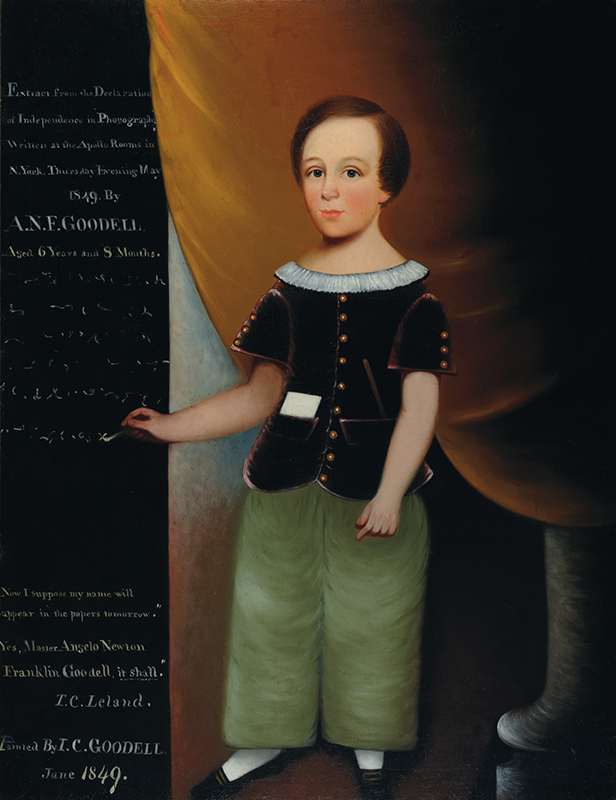

Fig. 3. Portrait of Angelo Newton Franklin Goodell [1842–1871] by Ira Chaffee Goodell (1800– 1877), 1849. Inscribed “Extract from the Declaration/ of Independence in Phonography/ Written at the Apollo Rooms in/ N.York. Thursday Evening May/ 1849. By/ A.N.F. GOODELL./ Aged 6 Years and 8 Months.” at left; and below “Now I suppose my name will/ appear in the papers tomorrow./” Yes, Master Angelo Newton/ Franklin Goodell, it shall. / T.C.Leland.” and “Painted By I.C.GOODELL/ June 1849.” Oil on canvas, 43 1/2 by 33 inches. Collection of Suzanne and Michael R. Payne.

Many folk portrait painters settled down in urban areas and found commissions among the newly prosperous. John Bradley, an immigrant from Great Britain, began his American career on Staten Island, where he painted portraits of some of the borough’s most prominent residents. Asher Androvette’s portrait (Fig. 1) is the earliest known signed and dated painting by Bradley in the United States and proves that he was living and working on Staten Island by 1832. In a history of Staten Island, the Huguenot Androvettes are described as an “old French family” who were early settlers of Westfield. The Androvettes are further related by marriage to the prominent Coles and Tottens, who also figured among Bradley’s Staten Island sitters.

After a period of itinerancy in his youth, Ira Chaffee Goodell settled with his wife and family in New York City in April 1834. Over the years, the family moved many times within the city, possibly as a result of the changing fortunes of the artistic life.2 Goodell described the rise and fall of his profession in the city in a letter to his sister-in-law:

In this City, thirty years ago there were nearly two hundred Portrait Painters. Now, I doubt if there is fifty, and nearly all of these are of the first class artists and are patronised by the Wealthy, paying from three to five hundred dollars apiece.—I think Hard Times and Photography, has Slain Common Portrait Painters.3

Fig. 4. Captain Jinks show figure, possibly by Thomas J. White (1825– 1902), c. 1880. Paint on wood; height 75 (including base), width 17, depth 17 inches. Collection of John and Barbara Wilkerson; photograph by Ellen McDermott.

Goodell participated in many of the “intellectual” pursuits of the mid-nineteenth century, including phrenology, mesmerism, clairvoyance, and phonography, an early form of shorthand. He taught phonography to his son Angelo Newton Franklin Goodell who, at age six, wrote the Declaration of Independence from memory in phonography before a large audience at the Apollo Rooms in May 1849. Ira Goodell commemorated the event with a large, ambitious portrait of Angelo performing the amazing feat (Fig. 3) including Angelo’s statement that “Now I suppose my name will appear in the papers tomorrow.”

Fig. 5. Carousel camel attributed to the workshop of Charles I. D. Looff (1852–1918), 1875–1900. Paint on wood; height 44 1/2, width 50 1/2, depth 9 inches. Collection of Kendra and Allan Daniel.

New York City’s prominence in shipbuilding from about 1820 until after the Civil War gave rise to an active community of ship carvers. When the shipbuilding business began to decline in the 1850s, a number of them turned their skills to creating show figures—the statuesque caricatures, such as cigar store Indians, used as advertising. By 1860, show figures were ubiquitous across America—with images of Turks, Scotsmen, fashionable women, and the like crowding city pavements. New York City remained the center of production and distribution, and the expressive “New York Style” of show figure was in demand throughout the country.

As in their ship-carving days, New York City figure carvers worked together in the same workshops, sharing skills, and artistic sensibilities. Thomas White, the probable carver of the figure of “Captain Jinks”— hero of a popular song in the post–Civil War era—is known to have worked with Samuel Robb (1851– 1928), the best-known and most prolific artist of the New York school of show figures. The face of “Captain Jinks” (Fig. 4) is believed to be a portrait of Robb. By the end of the nineteenth century, show figures were increasingly viewed as an old-fashioned mode of advertising and were gradually replaced by modern electric signs.

Some carvers found work in the shops of carousel manufacturers. Many of the greatest of these carvers were European immigrants, such as Charles I. D. Looff, a founder of the “Coney Island Style” of carousel carving, characterized by flamboyant horses bedecked with jewels and gold and silver leaf.

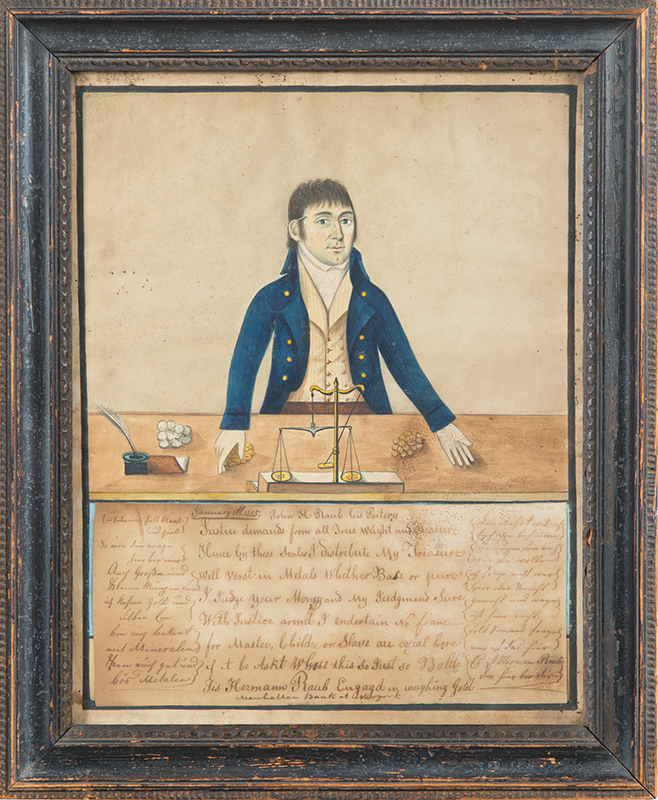

Fig. 6. Herman Raub Engaged in Weighing Gold at the Manhattan Bank at New York, artist unknown (possibly “Mr. Thompson”), 1805. Watercolor and pen and ink on paper; 15 3/4 by 13 inches including original frame. Private collection; photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

Looff emigrated from Holstein (then part of Prussia) in 1870, and found work in a furniture factory— and as a part-time ballroom dance instructor—and began carving animals from scraps of wood from the factory. In 1876 he installed carved horses and other animals on a rotating circular platform at Lucy Vanderveer’s Bathing Pavilion at West Sixth Street and Surf Avenue, thus creating Coney Island’s first carousel. Looff then opened a factory at 30 Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn, where he employed a number of expert carvers who later went on to establish their own businesses. As well as horses, Looff’s enterprise created animals previously seen in America only in zoos, circuses, and P. T. Barnum’s museum—including the camel (Fig. 5).

Folk artists were drawn to the commercial life of New York City, depicting new technological marvels, everyday transactions, and business people of all ranks. An 1805 watercolor portrait (Fig. 6) of John Herman Raub, identified in that year’s city directory as a “counter” at the Manhattan Bank of New York (forerunner of the Chase Manhattan Bank, now JP Morgan Chase) shows him at work with a set of scales, a pencil tucked behind his ear. An appended poem handwritten in English and German defends his honesty and skill and points out that “Master, Child, or Slave are equal here.” Raub prospered enough that, in the US census of 1820, he is, ironically, recorded as the head of a household that included one male slave.

Fig. 7. Goddess of Liberty weather vane, possibly by J. L. Mott Iron Works, New York, 1880–1900. Paint and gold leaf on copper and zinc; height 43, width 52, depth 4 inches. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher.

The best-known New York City weather-vane makers—J. W. Fiske and Company, E. G. Washburne and Company, J. L. Mott Iron Works, among others—copied each other’s forms and it is often difficult to distinguish the vanes of one company from another’s. Although described as factory-made, these weather vanes actually involved a great deal of individual handwork. A copper or copper and zinc weather vane began with a number of carved wood or cast-iron molds. The copper was then hammered around the molds, cut, soldered together, filed, and gilded.

Jordan Lawrence Mott (1798–1866) was listed as a “grocer” in Longworth’s New York City Directory from 1824 to 1834. By 1842 his occupation had changed to “stoves,” after he invented the first cook- ing stove that burned anthracite coal as fuel. Mott originally made the stoves in a small foundry at the rear of his store on Water Street in Manhattan; however, a rapid increase in business led him to purchase an extensive tract of land in the South Bronx for a new iron works. An entire village rose around it, and the area is still known as Mott Haven. Mott’s descendants continued to operate the firm in the Bronx until the first years of the twentieth century, when it moved to Trenton, New Jersey.4

The Goddess of Liberty weather vane (Fig. 7) is attributed to Mott’s company based on its similarity to one illustrated in the 1892 Mott catalogue.5 Beginning about 1865, weather vane manufacturers marketed designs that appealed to the patriotic spirit of post–Civil War America, as well as the expansionist mood of the country. A number of similar vanes were produced, most combining classical clothing with a Phrygian cap (a symbol of freedom in ancient Rome) and the American flag. The hand indicating the wind direction can also be interpreted as directing the country forward.6

Fig. 8. Two-gallon crock by W. A. MacQuoid and Company Pottery Works, New York, c. 1869. Stamped “WM-A MACQUOID &CO/ NEW-YORK./ LITTLE WST. 12TH ST./ 2” and inscribed “Gold $1.44 1/2.” Stoneware with cobalt decoration; height 11 1/2, diameter 10 1/2 inches. Private collection; Ashworth photograph.

Scandals, crashes, and dirty dealing are topics that invariably arise when discussing the history of Wall Street and the financial markets. Before the 1929 stock market crash, the term “Black Friday” referred to September 24, 1869, the day the price of gold reached $144.50 per ounce (as commemorated on the two-gallon crock shown in Fig. 8) and sent the US financial sector into chaos. Speculators Jay Gould and Jim Fisk had attempted to corner the market by leading a conspiracy to buy all the country’s outstanding gold, artificially inflating the price. President Ulysses S. Grant learned of the manipulation and ordered the government to release $4 million in gold, driving down the price and crushing the gold ring’s scheme. Panic on Wall Street followed, and many who had invested heavily in gold were ruined.7

Fig. 9. Situation of America, 1848, artist unknown, 1848. Oil on wood; height 34, width 57, depth 1 3/8 inches. American Folk Art Museum, Esmerian gift.

By 1800 the port of New York handled nearly one-third of the new nation’s overseas trade and almost one-quarter of its coastal trade.8 The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 only increased the city’s importance to shipping. Certainly the “Situation of America” in 1848 appeared rosy, as shown by the painting on panel of that name (Fig. 9). The painting depicts the Manhattan skyline as seen from the Brooklyn waterfront. The paddle wheeler Sun, smoke pouring from its stacks, has either unloaded its freight or is waiting to set off with a new load. A freight train, piled high with sacks and crates, is rolling away.

In 1814 Robert Fulton formed the New York and Brooklyn Steam Ferry Boat Company, and cut the time of a voyage from Manhattan to Brooklyn to between four and eight minutes. The speed and regularity of the ferry service raised land values in Brooklyn, and helped create New York City’s first commuter suburb.

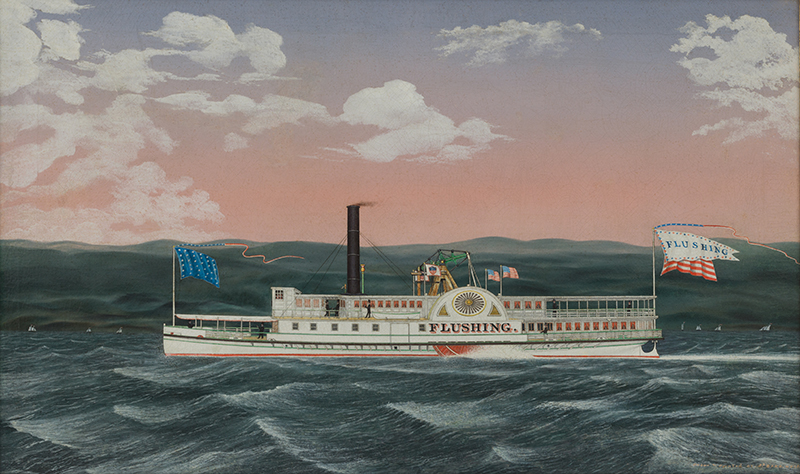

Fig. 10. Flushing by James Bard (1815–1897), c. 1877. Inscribed “Drawn & Painted By J. BARD NY 1877” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 by 49 inches. Queens Historical Society, Flushing, New York.

Twin brothers James and John Bard specialized in painting the steamboats that traveled the Hudson River to Albany, as well as local New York ferries, tugs, and sailing ships. For twenty years, the brothers painted together, with James continuing alone after John’s death in 1856. The James Bard oil painting of the Flushing (Fig. 10) is undated, but the ship was built by the Wilmington, Delaware, firm of Harlan and Hollingsworth in 1877.9 The Flushing was owned by the Long Island Rail Road, which began operating ferries between Hunters Point in Queens and Manhattan in 1859.10

The building at No. 7 ½ Bowery, Manhattan (Fig. 11), housed a number of businesses, including Pollock’s Fur Hat Manufactory, Smith and Brothers, and Phelps and Ensign Map Publishers. The wall signage on the middle row also names “Wriley Painter.” De La Prelette Wriley, presumed to be the artist of this oil on wood panel, was indeed listed in the city directory of 1841 as a painter at this address.

Fig. 11. No. 7 1/2 Bowery, New York City by De La Prelette Wriley (1809– 1873), c. 1837–1839. Oil on wood panel, 20 by 24 3/4 inches. New-York Historical Society; photograph © New-York Historical Society.

Wriley was a sign painter by profession. His obituary in the New York Daily Tribune of December 30, 1873, notes that he worked for the firm of Willett L. Washburne and Robert Brown, a company that made “emblematic signs and weather vanes.”11 According to the report, Wriley “acted in a singular manner, and wore fantastic garments. For years past he has been almost insane upon the subject of spiritualism.” Wriley wrote obsessively in a book under “spiritual” inspiration. At the time of his death, he was rewriting the Constitution of the United States. He frequently stated that, when his book was finished, he would have nothing left to live for, and he would destroy himself. He finally did, stabbing himself dead in the workshop of Washburne and Brown. According to the Tribune, he left instructions to send his body “first to one wise sage of Brooklyn, and finally to a Dr. G. G. Atwood. His head, however, he ordered to be given to Messrs. Fowler & Wells, the phrenologists.”

Made in New York City: The Business of Folk Art is on view at the American Folk Art Museum in New York from March 19 to July 28. This article is excerpted and adapted from the accompanying book of the same title, published by the American Folk Art Museum.

1 John L. Scherer, Art for the People: Decorated Stoneware from the Weitsman Collection (Albany, NY: New York State Museum, 2015), p. 36. 2 All information on Ira Chaffee Goodell is from Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne, “In His Own Words: The Discovered Writings of Ira Chaffee Goodell (1800–1877), A Nineteenth Century American Folk Portrait Painter,” Antiques and Fine Art, vol. 14, no. 3 (Autumn 2015), pp. 254–261. 3 Ibid, p. 261. 4 Walter Grutchfield, “The J. L. Mott Iron Works,” waltergrutchfield. net, 2012. 5 David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles, Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence: Selections from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana (Seattle: Marquand Books, 2006), p. 382. 6 Richard Miller, “Folk Sculpture: For Diversion and Utility,” ibid., p. 237. 7 “The Black Friday Gold Operations— The Suit Against Gould and Fisk for About $2,500,000,” New York Times, December 8, 1870, p. 2. 8 Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 334. 9 Brian J. Cudahy, Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor (New York: Fordham University Press, 1990), p. 447. 10 Ibid, p. 69. 11 “Suicide of a Spiritualist,” New York Daily Tribune, December 30, 1873, p. 5.

ELIZABETH V. WARREN is the curator of Made in New York City: The Business of Folk Art. She is an author, collector, independent curator, and authority on textiles and folk art.