In the realm of nineteenth-century American furniture design, certain makers’ names have transcended the scholarly arena to enter the wider public consciousness. Scottish-born Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854), the young nation’s most celebrated and original cabinetmaker, created works that embodied the neoclassical ideal of its time; German-born John Henry Belter (1804–1863) is best known for elaborately carved chairs and sofas in laminated rosewood that represent the peak of antebellum rococo revival ebullience. During the post–Civil War era of industrial growth, prosperity, and political corruption, which Mark Twain named “the Gilded Age,” the leading tastemaker to the newly rich was the firm Herter Brothers. Among its rivals, and long overdue the limelight of a consecrated museum show, was the innovative partnership of German-born Anton Kimbel (1822–1895) and French-born Joseph Cabus (1824–1898).

Although Kimbel and Cabus’s reputation is familiar to collectors, the breadth of the firm’s creativity is less widely appreciated. The Brooklyn Museum’s new show, Modern Gothic: The Inventive Furniture of Kimbel and Cabus, 1863–82, promises to rectify that. The exhibition has been organized by guest curator Barbara Veith in consultation with Medill Higgins Harvey of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They built on the exhaustive work—informed by a keen eye—of the late Barry R. Harwood, who served for three decades as the Brooklyn Museum’s esteemed curator of decorative arts. With his guidance, the museum assembled the nation’s largest institutional collection of Kimbel and Cabus furniture. By bringing to fruition Harwood’s longtime intentions, this exhibition does abundant honor to his memory.

The show features more than sixty objects, among them outstanding pieces from the museum’s collection, supplemented by choice examples from the holdings of such institutions as the Met and the Baltimore Museum of Art, and from private collections, including that of Barrie and Deedee Wigmore.

The exhibition catalogue discusses in detail each Kimbel and Cabus object in the show. Pieces are also shown in historic images that provide a vivid idea of how these furnishings were displayed in the firm’s showrooms, and subsequently in domestic settings. The catalogue essays—by Veith and Harvey; Max Donnelly, of the Victoria and Albert Museum; Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, of the Met; and Berlin-based art historian Melitta Jonas—embody the most recent international scholarship in this compelling facet of nineteenth-century American design. Moreover, the show and catalogue essays bring to life two important American craftsmen who until now have been a mere brand name.

Mid-nineteenth-century New York was an increasingly sophisticated city whose cultural institutions were the finest in the nation. There were annual exhibitions at the National Academy of Design (founded in 1825), regular performance seasons by the Philharmonic Society of New York (today’s New York Philharmonic) established in 1842, and appearances by leading European and American musicians and actors.

Naturally, this vigorous metropolis was a major center of American decorative arts, especially fine furniture. Before and after the Civil War, leading New York makers included Belter and his native New York rival Charles Baudouine, the German born Gustave and Christian Herter; French-born Léon Marcotte; the partnership of French-born Auguste Pottier and native New Yorker William P. Stymus; and another German expatriate, George A. Schastey. It was into this competitive community that Anton Kimbel began to make his way upon arriving in 1848. Scion of a cabinetmaking family in Mainz, he served his apprenticeship in his father’s workshop and that of his uncle Philipp Anton Bembé. The latter’s faith in Anton’s talent led him to sponsor his nephew’s advanced training in Brussels, Paris, and St. Petersburg. Hence, the twenty-six-year-old shipped to America boasting an exceptionally international vocabulary of contemporary styles and decorative techniques, including carving, upholstering, and even complete interior decoration— a European idea as yet unfamiliar to the New York carriage trade. By 1854 Kimbel had not only achieved his own reputation but had established his own business, Bembé and Kimbel, Furniture and Upholstery. Uncle Bembé, still based in Mainz, financed the enterprise, keeping his nephew alert to the latest European trends.

Bembé and Kimbel prospered, in 1857 clinching an assignment to produce 131 oak armchairs for the United States House of Representatives during the expansion of the Capitol, a major construction project begun in 1851. Kimbel manufactured the chairs to an official design created by Thomas Ustick Walter (1804–1887), architect of the Capitol expansion project and most notably designer of the building’s iconic dome. As carried out by Bembé and Kimbel, the chairs are in a monumental Renaissance-revival style, with beautifully carved details.

After the Capitol project, Kimbel endured a period of struggle and the loss of his business initiated by the death of his uncle in 1861. But he was eventually able to regain his footing and embark on the creative partnership with Joseph Cabus that would ensure their joint immortality.

We know relatively little of Cabus’s early training. Eight years old when his family departed France for New York in 1833, he may have apprenticed with his father, Claude, who is listed as a cabinetmaker in the 1838 city directory. Joseph himself first appears as a cabinetmaker in the 1850 directory. Later in that decade, he worked for Alexander Roux, eventually rising to join in a brief partnership, which ended in 1860. Presumably, working with Roux would have reinforced Cabus’s stylistic versatility and refinement.

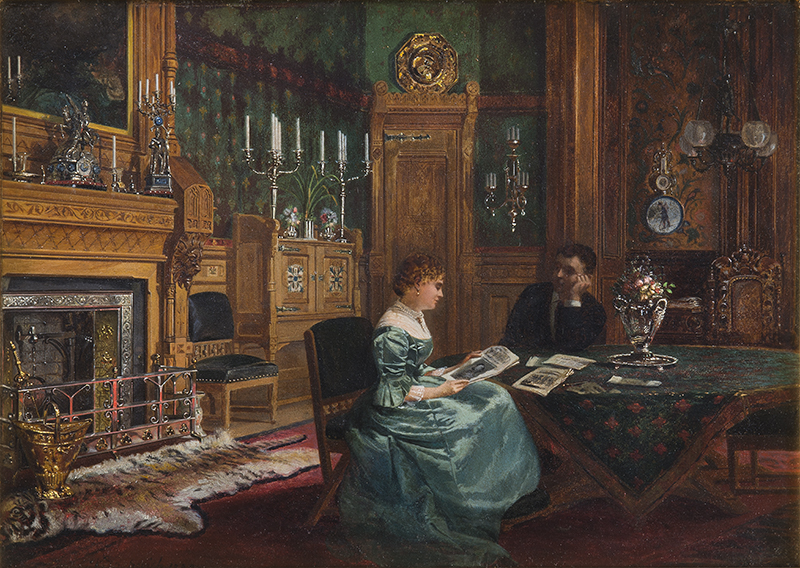

Certainly, Kimbel and Cabus’s journeyman years had ended by 1863, the year their firm first appeared in the city directory. By late 1867 they were advertising nationally, having grown from a modest concern serving larger establishments into major players themselves, fashioning “the most elaborate and plain Drawing-Room, Library, Bed- and Dining-Room Suites . . . and Decorations in general.” Beyond furniture, which they created at a range of prices to attract a broad clientele, they now offered complete interior decorating services.

By 1870 Kimbel and Cabus were firmly established. And for all their ability in the rococo and Renaissance revival styles (including the Neo-Grec substyle), as shown in an elaborate rosewood drawing room cabinet replete with fluted columns, marquetry side panels and central medallion (Fig. 7), their embrace of modern Gothic style lent the firm a reputation for progressive ideas. This novel style represented a refreshing take on the eighteenthcentury Gothic revival, which in Britain had enjoyed popularity into the early nineteenth century and which was popularized in America by architects Alexander Jackson Davis and Andrew Jackson Downing.

That first revival had embodied the early romantic spirit, initially as a picturesque, ideological retort to the cool severity of Palladian neoclassicism, which had dominated English style since the early eighteenth century. During the 1830s, as burgeoning steam technology fostered growing urbanization and industrial gloom, the Gothic style was fervently championed by the architect Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) and further encouraged during the 1860s by an upcoming generation of designers, which led to the emergence of a new version of the revival, known as modern, or reform, Gothic, which eschewed the curvilinear profiles of the preceding rococo and Renaissance styles and their abundant, realistically carved surface ornament. Modern Gothic favored straight clean lines that revealed the construction of a piece, and restrained, stylized decoration carved in low relief.

These principles were espoused by the entrepreneurial William Morris and by architects/designers such as Bruce Talbert (1838–1881) and Charles Locke Eastlake (1836–1906) who promoted a return to hand craftsmanship over machines—at least in theory. Eastlake would publish A History of the Gothic Revival in 1872, having achieved great influence with his 1868 book Hints on Household Taste, subsequent American editions of which became standard wedding gifts for a generation and prompted countless households to adopt what was erroneously called “Eastlake-style” interiors, a term that Eastlake himself repudiated. Under their considerable influence, Kimbel and Cabus often adopted designs by Talbert and by the German- Jewish architect-designer Edwin Oppler (1831–1880).

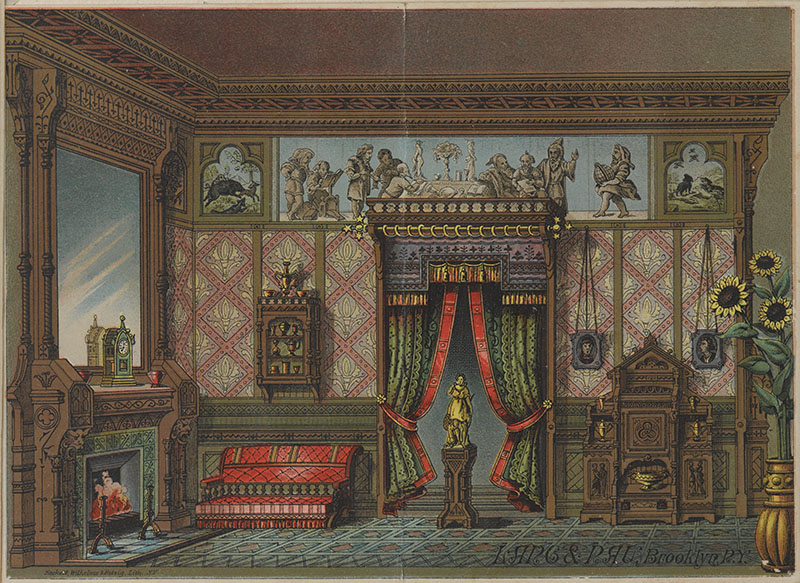

“Ebonized” wood—often cherry with an applied black finish—was a characteristic medium of much modern Gothic furniture, and it was used by Kimbel and Cabus and other makers. While Herter Brothers, serving the highest end of the market, embellished their custom-made furniture using luxurious rosewood and satinwood, intricate marquetry, ivory inlay, and hand-painted panels, Kimbel and Cabus, serving a broader market base, achieved memorable decorative effects with more modest ornament, including elaborate brass or nickel-plated hardware (some of their strap hinges on furniture pieces in the exhibition recall the complex beauty of illuminations in the ancient Book of Kells), transfer-printed ceramic tiles, and applied paper panels printed with images by British designers Christopher Dresser and Charles Rossiter.

More than the materials, however, Kimbel and Cabus’s exceptional design sense distinguished the firm in the marketplace. Its modern Gothic pieces are often at a remove from objects created during the eighteenth century and early Victorian Gothic revival. In that earlier period, easily recognizable architectural features such as pointed arches, trefoils, quatrefoils, and rows of leafy crockets were often adapted from stonemasonry to cabinetry, exemplified by the American rosewood and mirror glass étagère in the opening section of the show, its pinnacles, spire-like cresting, and soaring verticality evoking a church steeple (Fig. 14).

Similarly, their “Hanging Key Cabinet” of about 1874 with its elaborate pierced foliate carving top and bottom, its slender flanking colonettes, elaborate strapwork hinge, and tall spire culminating in a leafy finial, recalls the earlier Gothic revival manner (Fig. 20).

There is a Janus-like quality to the modern Gothic. On one hand, the style was intended to embrace the romantic spirit of Gothic’s distant past. On the other, postbellum America embraced relatively clean-lined modern Gothic style as a genuinely modern, visually reformed answer to what was perceived as the excessive elaboration of the rococo and Renaissance-revival styles. Indeed, for all the elegance achieved by means of simple surface ornament, it is the distinctive, even protomodernist shapes that distinguish a Kimbel and Cabus’s sofa of about 1875, adapted from an Oppler design, with its intersecting diagonal legs and arms (Fig. 16), and an elegant walnut desk with a wealth of cubbyholes and cabinets steadily supported by the splayed front legs (Fig. 6).

Kimbel and Cabus also lavished design ingenuity on parlor cabinets, sideboards, desks, and similar case pieces in characteristic ways. Hanging cabinets, a popular modern Gothic accoutrement, offered a variety of decorative applications, and this one- or two-door element was frequently incorporated into Kimbel and Cabus writing desks and étagères as well, offering storage space while lending eye-catching emphasis to the overall form of the furnishings. Whether in ebonized or natural woods, the firm’s cabinetry makes a conspicuous architectonic statement, especially when diagonal profiles to the cresting impart the suggestion of a gabled roof (Fig. 8).

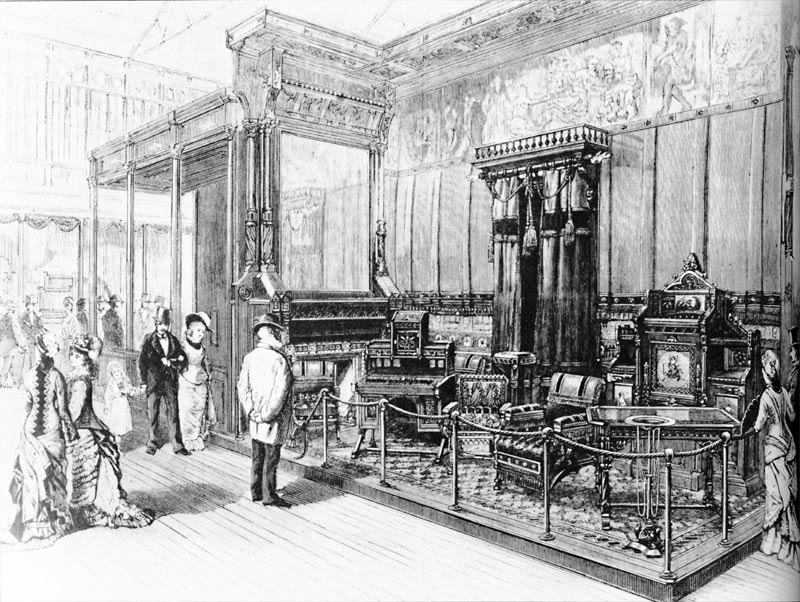

As this refreshed Gothicism exerted itself on Gilded Age American decorative arts, Kimbel and Cabus rapidly distinguished itself as one of the style’s most imaginative and innovative exponents. The climax came with the firm’s appearance at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where it created a complete modern Gothic room display (Fig. 5). Replete with a parquetry inlaid floor, a scenic painted frieze, an elaborate doorway with a spindle-galleried overdoor, an immense mirrored and tiled mantelpiece, and choice examples of their chairs and cabinets, the display was lauded by one commentator as “rich and tasteful enough to rank it among the very best of the American exhibits in household art.”

Although the competition included displays by 176 other American furniture manufacturers, the firm’s star shone more brightly than ever. Between winning two awards and being viewed by many of the exposition’s nine million visitors, the firm’s triumphant appearance marked the zenith of the partnership. Its enhanced reputation—which the company promoted liberally—elicited multiple private and public decoration commissions, making Kimbel and Cabus the nation’s supreme purveyor of modern Gothic design.

Ironically, strict modern Gothic style—if any late Victorian style could be called strict—was already yielding to such eclectic variants as “Queen Anne” (its woodwork often adapting motifs from the early seventeenth-century styles prevalent in the reigns of James I and Charles I) as the decade waned. When Kimbel and Cabus won the prestigious commission to furnish the Tenth Company K Room at the newly dedicated Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue at East Sixty-Sixth Street between 1879 and 1880, they did so to the Queen Anne designs of Company K member Sidney V. Stratton, from the pre-eminent New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White.

Indeed, as England’s aesthetic movement began to exert its influence in America, Kimbel and Cabus was able to switch stylistic gears to meet the new trend. Nevertheless, a disagreement between the partners led to their breakup in May 1882. Each established a separate business: A. Kimbel and Sons produced aesthetic movement designs during the 1880s before focusing on European revival styles that became fashionable again in the 1890s. Following Anton’s death in 1895, his sons and grandsons remained in business as late as the 1940s. Cabus opened a new factory, working with Louis Comfort Tiffany, McKim, Mead, and White, and others, carving and finishing woodwork interiors, among them those of the Villard Houses on Madison Avenue, behind Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Until his death in 1898, Cabus and his son carved picture frames to Stanford White designs for White’s many interior schemes.

Ultimately, whatever differences caused the premature dissolution of their partnership, Kimbel and Cabus will always be united in the admiration of those who appreciate the distinctive vitality of later nineteenth-century American design. Now, the Brooklyn Museum exhibition invites visitors to delve into the manifold pleasures of that legacy.

Modern Gothic: The Inventive Furniture of Kimbel and Cabus, 1863–82 is on view at the Brooklyn Museum to February 13, 2022. The information in this article, including quotations, is taken from the accompanying catalogue, edited by Barbara Veith and Medill Higgins Harvey and published by the Brooklyn Museum and Hirmer.