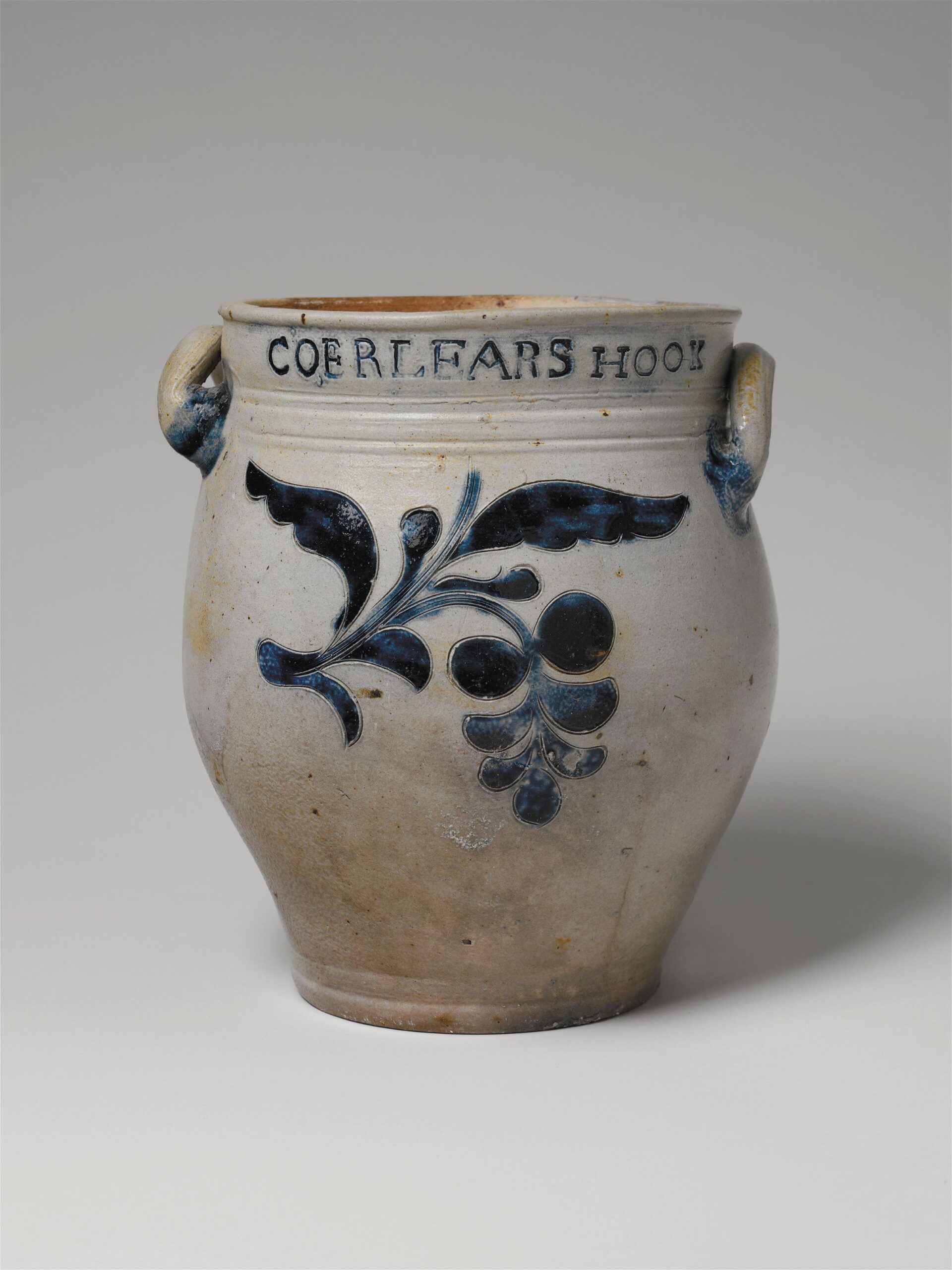

Fig. 1 Jug by Thomas W. Commeraw (c. 1771– 1823), New York City, 1800–1819. Marked “COMMERAW.S STONEWARE N• YORK CORLEARS HOOK” around the shoulder. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 15, diameter 11 inches. Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki; photograph by Robert Hunter.

On entering the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Free Black Potter Thomas W. Commeraw, visitors will encounter a three-gallon jug of exceptional ovoid form. This jug, never before displayed in public, is a masterful example of the distinctive style of early New York City salt-glazed stoneware. It is also an expression of an individual’s touch: that of the Black potter Thomas W. Commeraw, who stamped this pot with his characteristic exuberant multiple bowknots, which extend across its upper belly to form a linked ring of swags and tassels below its neck. With its bright clear cobalt, luminous clay quality, and found its way into public collections, Commeraw’s work was naturally grouped with that of other New York City stoneware makers. This led to the mistaken assumption that he was, like them, of white European descent. In 2003, however, auctioneer and researcher A. Brandt Zipp found Commeraw listed as “black” in the 1810 US Census and began a years-long project that culminated in the recent publication of Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner.1 Historical investigation reveals that Commeraw, in fact, consistently self-identified, and was identified by others, as “Black,” “Colored,” or “of African descent.” He participated with fellow free Black men in numerous initiatives advocating for full citizenship, equality, and humanity, in a context where slavery was still in force and racial prejudice was the norm. He did so, and supported his family, by turning out some of the highest quality stoneware of his era.

Fig. 1a. Jug by Thomas W. Commeraw (c. 1771– 1823), New York City, 1800–1819. Marked “COMMERAW.S STONEWARE N• YORK CORLEARS HOOK” around the shoulder. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 15, diameter 11 inches. Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki; photograph by Robert Hunter.

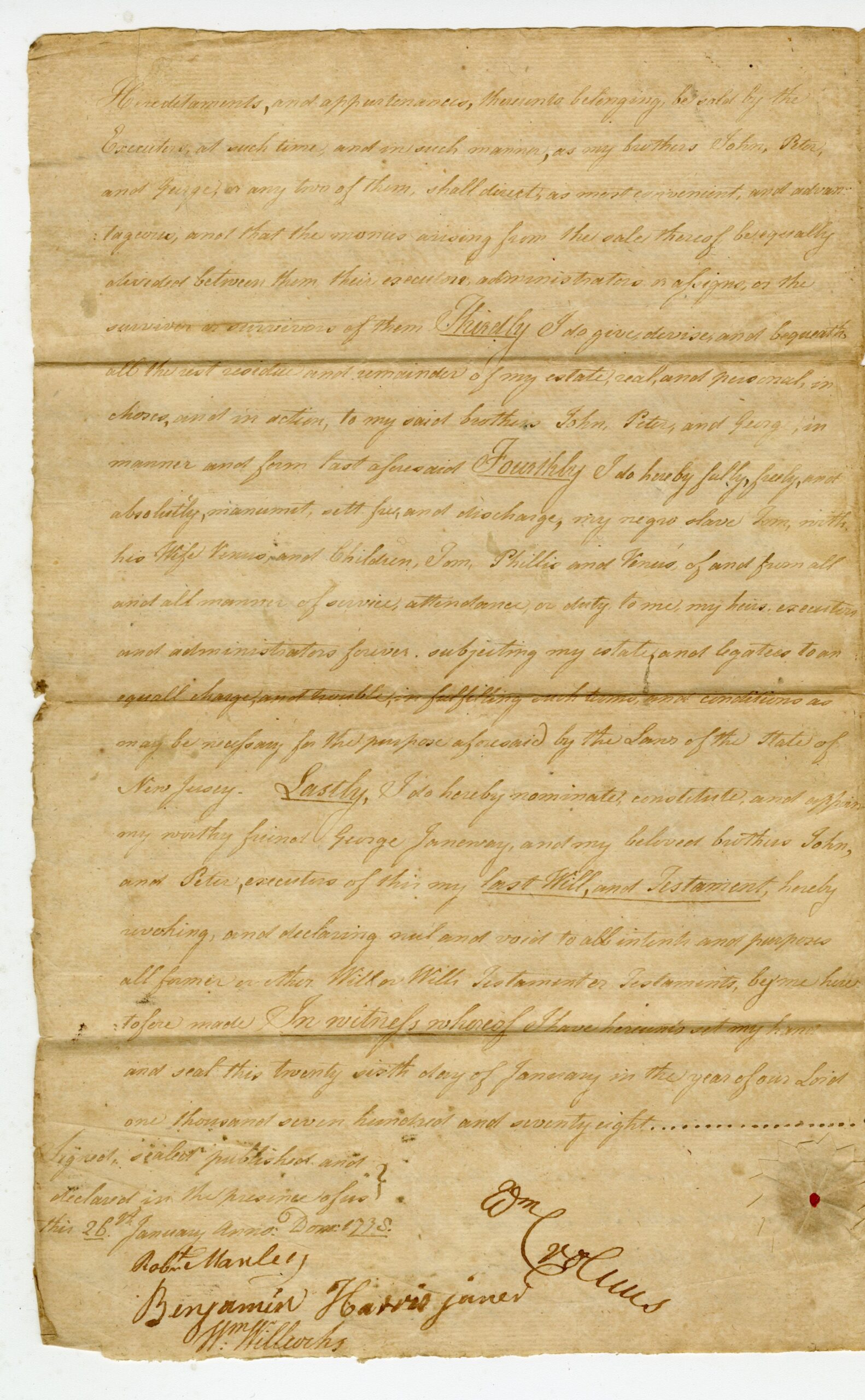

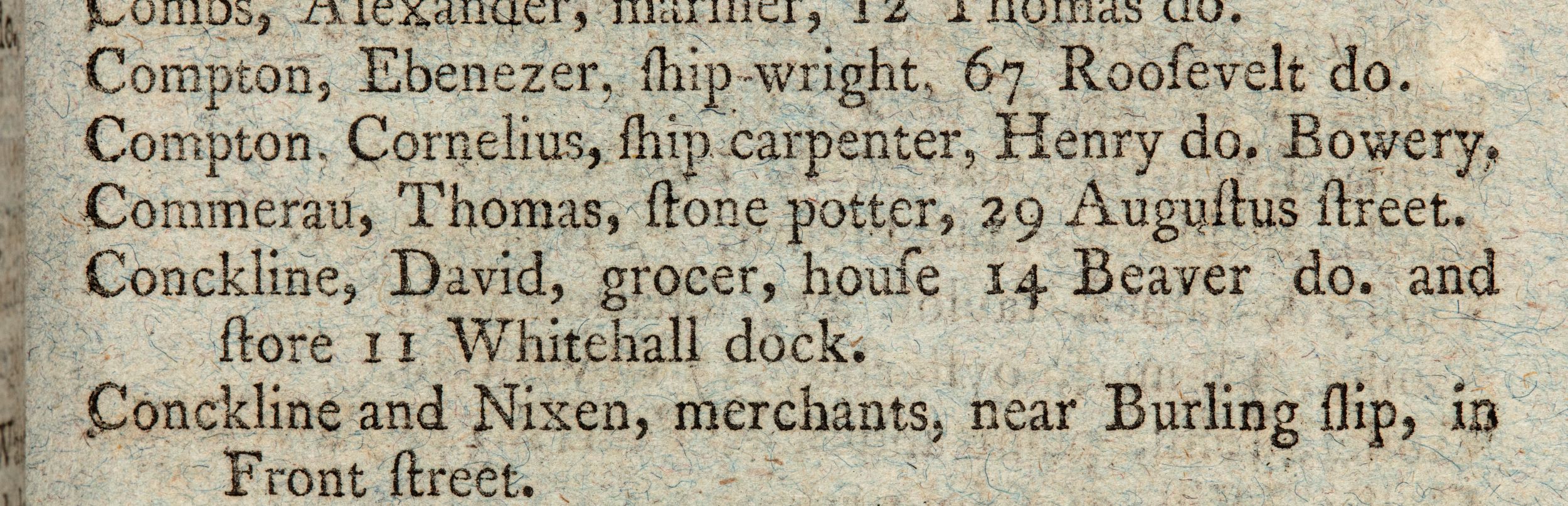

Commeraw’s work has always been closely associated with that of the more famous Crolius family, the German immigrant potters who brought the stoneware tradition to New York in the 1720s and flourished for many generations (Fig. 3). Commeraw almost certainly trained at one of their potteries, but his connection to the family was in fact more existential: William Crolius, a second-generation patriarch-potter, had enslaved Commeraw’s family, manumitting them in his 1778 will (Fig. 2). A patriot who decamped to New Jersey during the British occupation of New York City, Crolius unconditionally freed Commeraw’s parents and their three children, Tom (Thomas W.), Phillis, and Venus. For an enslaved family to be intact and living under one roof was unusual, attesting perhaps as much to Crolius’s financial ability to support a large household as to his anti-slavery leanings.2 Commeraw’s father must have worked in Crolius’s workshop while he was enslaved. Whether Commeraw himself was ever formally apprenticed after his manumission is unknown, though his proximity to the potteries when he was first listed in the 1795 directory as a “stone potter,” living just blocks away from Pot Baker’s Hill near today’s City Hall, suggests that he was working in the potteries there as a journeyman (Fig. 5).

Commeraw stamped his workshop location on his pots: “COERLEARS HOOK” and “N•YORK.” Since the city was known for high-quality stoneware, asserting this provenance added value. Commeraw’s marking signaled both his pride in craftsmanship and directed buyers to his shop

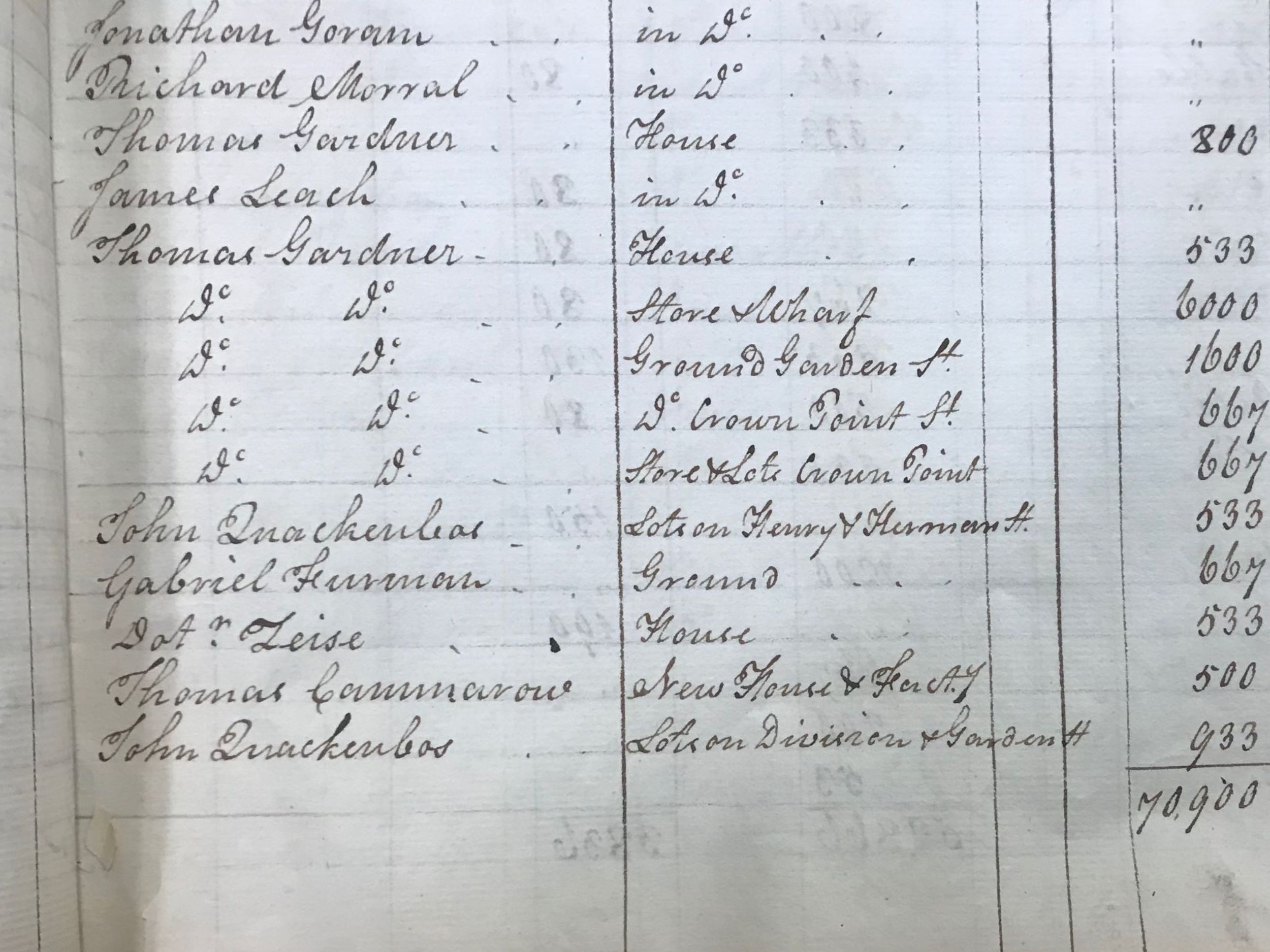

In 1797 Commeraw struck out on his own, establishing an independent workshop at Corlears Hook, in the Seventh Ward, a growing manufacturing and shipbuilding neighborhood near the anchorage of the present-day Williamsburg Bridge. Crafting Freedom includes a copy of a 1799 tax assessment of his home and workshop (Fig. 6). Though only in his twenties, he had attained the status of independent master craftsman, an exceptional achievement for any artisan in that period, when changing labor practices were making the transition from journeymen to master more difficult, and certainly unusual for a person of color.

Fig. 2. Detail of the will of William Crolius (1731–1779), Somerset, New Jersey, 1778, showing Crolius’s manumission of Commeraw’s family. New Jersey State Archives, Trenton.

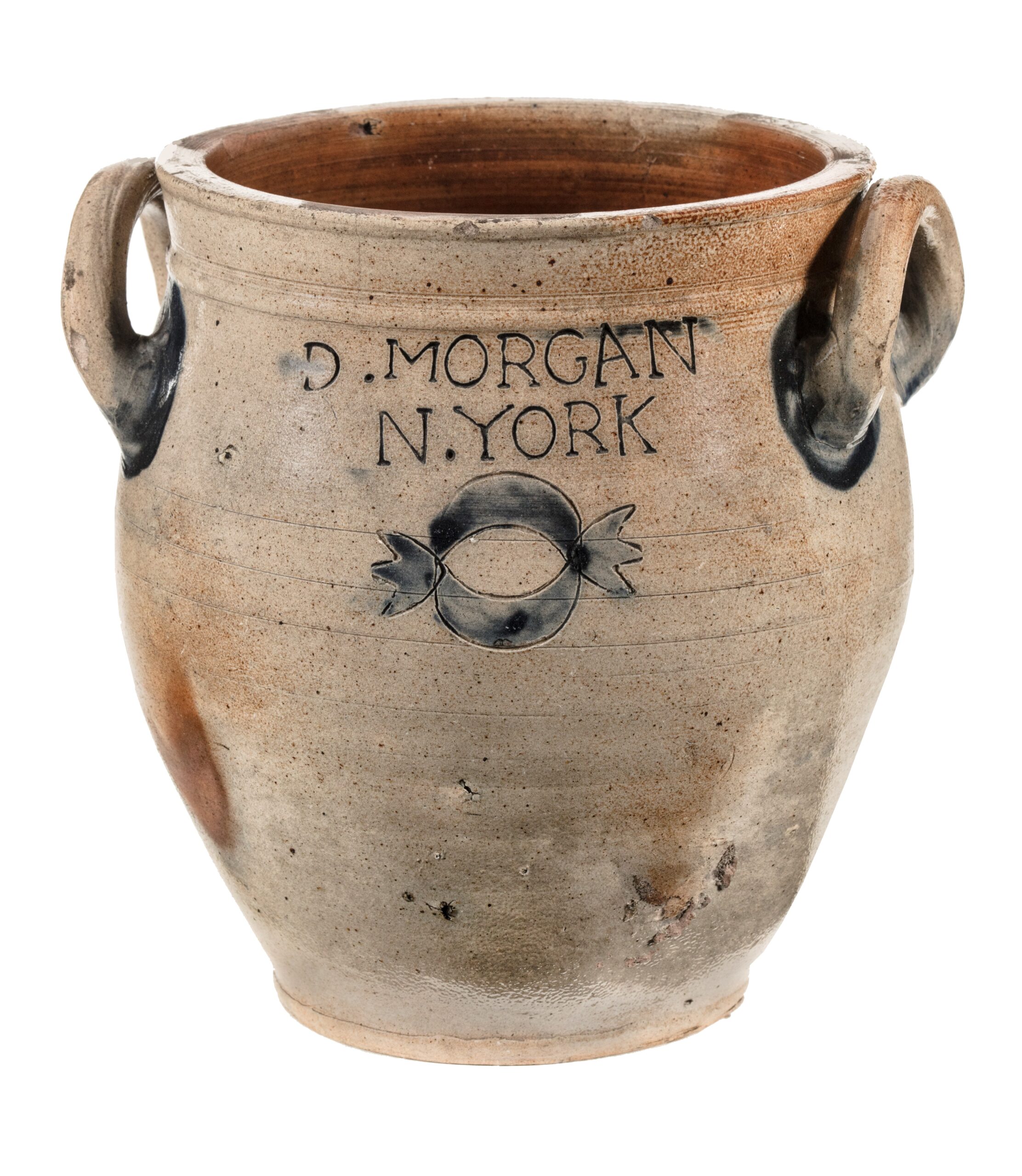

The following year, David Morgan, another journeyman potter who had lived near Pot Baker’s Hill, also moved to Corlears Hook. Although the exact nature of Morgan and Commeraw’s relationship is unclear, it is likely that Morgan worked with Commeraw during his first years there, since Morgan was rooming in a nearby house in 1799. By 1801 tax records show Morgan himself owning a pottery a few blocks from Commeraw. The two employed similar motifs, including swags, tassels, and bowknots (also called clamshells), though Morgan’s tassels were his own variations (Fig. 4). Morgan died a few years into the new century, though a son or brother, John Morgan, continued to work as a potter in the city and later moved to Virginia, where he carried on the decorative traditions of Commeraw and his presumed relative (Fig. 8).

Commeraw’s earliest stoneware was decorated with freehand incised and cobalt-infilled floral designs reflecting the prevalent eighteenth-century regional style, seen in a jar by Clarkson Crolius Sr. (Fig. 7). Commeraw stamped his workshop location on his pots: “COERLEARS HOOK” and “N•YORK.” Since the city was known for high-quality stoneware, asserting this provenance added value and engendered trust in consumers purchasing wares beyond the city. Commeraw’s marking signaled both his pride in craftsmanship and directed buyers in and outside the city to his shop. The exhibition includes several of these rarer incised vessels, including an outstanding example from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 9).

Around the turn of the century, Commeraw developed a motif featuring a ring of drapery-like semicircles that he incised individually with a compass (Fig. 10). From this, he developed a more streamlined method of decoration, impressing stamps into leather-hard clay to create his best-known designs. Stamping was more efficient, and consistent and crisper too. It imparted a visually impactful flourish to his wares, with the added advantage that the stamping could be executed by less-trained collaborators. These iconic embellishments functioned as a sort of logo, an emblem that would have been recognizable even from across a room (Fig. 11).3

While these swags and tassels were a common Federal-era device reflecting popular neoclassical tastes, Commeraw also playfully inverted and opposed these figures, creating his signature bowknots. The first of this group retained the stamped “COERLEARS/HOOK” and “N•YORK” used on the early incised floral motifs (Fig. 12). Later, he stamped his name, “COMMERAW.S” with a backwards S, and identified his product, “STONEWARE,” with a backwards N and an A with a v-shaped crossbar. Commeraw clearly knew the orientation of the letters N and S; they appear in the standard orientation in his other stamps. Whether his quirky typography was the casual result of mismatched, reappropriated typeface or a deliberate attention-attracting provocation is unclear (Fig. 13). On the works marked with his name, he continued to impress his location “CORLEARS/HOOK,” now using the more common spelling, and continued to use the “N•YORK” stamp from previous wares. These works constitute the bulk of his known production. Commeraw emerges as a pioneer in product branding, which he undertook with consistency and verve: the marks often take up a considerable portion of the pot’s surface, setting them apart from most of the similar efforts of his contemporaries (Fig. 14).

Fig. 3. Inkstand by William Crolius, New York City, 1773. Signed and inscribed “New York/ July 12th 1773/ William Crolius” on the bottom; removeable inkwell inscribed “Tyler” on the bottom. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 2 1/8, width 5, depth 5 1/2 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 4. Jar by David Morgan (active c. 1795–1803), New York City, c. 1798-1803. Marked “D. MORGAN/N. YORK” below the rim. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 9, width 8 1/4 inches. New-York Historical Society, purchased from Elie Nadelman; photograph by Glenn Castellano.

Fig. 5. Detail of the New-York Directory and Register (New York: William Duncan, 1795), listing Commeraw as stone potter living near Pot Baker’s Hill. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 6. Detail of the tax assessment of the Seventh Ward, New York, 1799, with Commeraw owning his new house and factory. New York City Records and Information Services, Municipal Archives; photograph by the author.

In addition to stoneware jugs, Commeraw made pickling jars for the city’s free Black oystermen, who comprised the majority of producers of this New York gastronomic specialty. These jars traveled far and wide, with examples recovered in South Carolina and as far away as South America. Many extant jars are attributed to Commeraw (based on the identical “N•YORK” stamp found on his marked pots). He made the jars for specific neighborhood oystermen, stamping their names and addresses prominently across the jars’ cylindrical faces (Fig. 15). As Commeraw participated in this Black economy, he opted not to promote his own enterprise, perhaps intentionally giving over the pots’ advertising space to his fellow New York Black entrepreneurs.

Crafting Freedom also documents Commeraw’s activities outside the workshop, including his work with other elite Black New Yorkers to advocate for full citizenship and equality. In 1807 he petitioned for the incorporation of an early mutual aid society to “assist those of their brethren who may stand in need of assistance, and as far as possible, to free others of their brethren from bondage.”4 While less known than the celebrated New York African Society for Mutual Relief, which was incorporated three years later and existed through the mid-twentieth century, the organization’s stated mission to emancipate those still enslaved was unusual for a Black organization in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

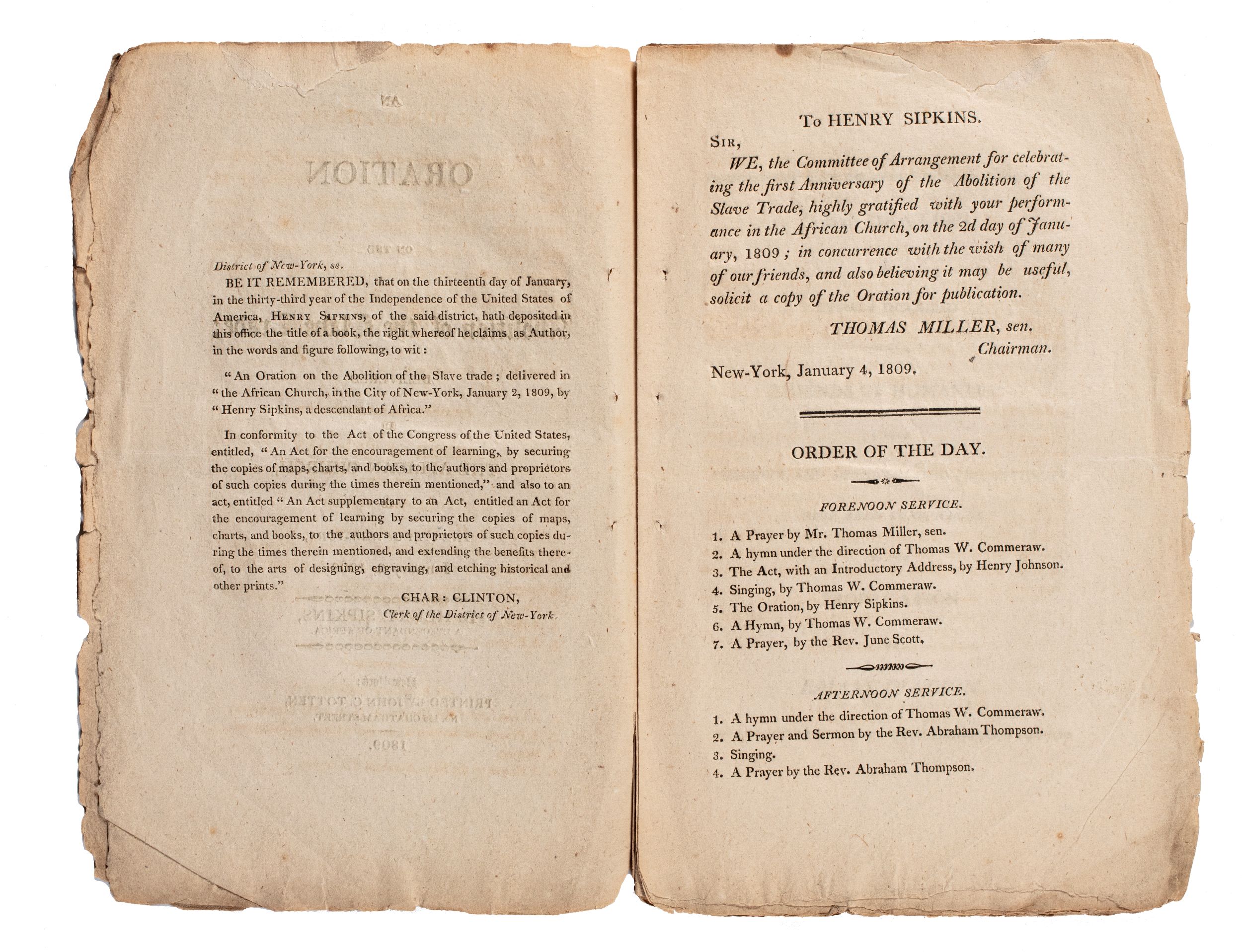

Commeraw was also an accomplished musician, a talent he marshalled for the cause of Black pride and solidarity, singing and directing the music at the second celebration of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade at New York’s first Black church in 1809. The previous year’s constitutional ban on the importation of enslaved people into the United States was seen by the Black community as a watershed moment marking progress toward abolition, and was celebrated annually by multiple Black organizations over the following decades. Not only did Commeraw sing and direct the music at the event, but he also authored an original hymn (Fig. 17).5

Fig. 7. Jar by Clarkson Crolius Sr. (1773–1843), New York City, c. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt and manganese oxide; height 15, diameter 11 1⁄2 inches. New-York Historical Society, gift of Samuel V. Hoffman; photograph by Glenn Castellano.

Fig. 8. Jar attributed to John Morgan (c. 1786–1850), Rockridge, Virginia, c. 1825–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 15, diameter 11 inches. Collection of Linda and Kurt Russ;photograph by Kurt Russ.

Fig. 9. Jar by Commeraw, New York City, c. 1797–1800. Marked “COERLEARS HOOK” and “N•YORK” on reverse of the rim. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 9 1/2, diameter 8 1/2 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 10. Jar by Commeraw, New York City, early 1800s. Marked “COMMERAW.S STONEWARE” on the belly. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 5 3/4, diameter 7 ½ inches. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Fig. 11. Jar by Commeraw, New York City, c. 1800–1819. Marked “COMMERAWES/STONEWARE” on the front and “N•YORK/ HOOK/ CORLEARS”on the back. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 13, diameter 8 inches. New-York Historical Society, gift of Samuel V. Hoffman; photograph by Glenn Castellano.

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Commeraw worked to assert Black voting rights and advocated for candidates committed to abolition. The year 1811 saw the first of a series of voting laws aimed at suppressing the Black vote by requiring documentation of voters’ free status, filing, and the payment of fees.6

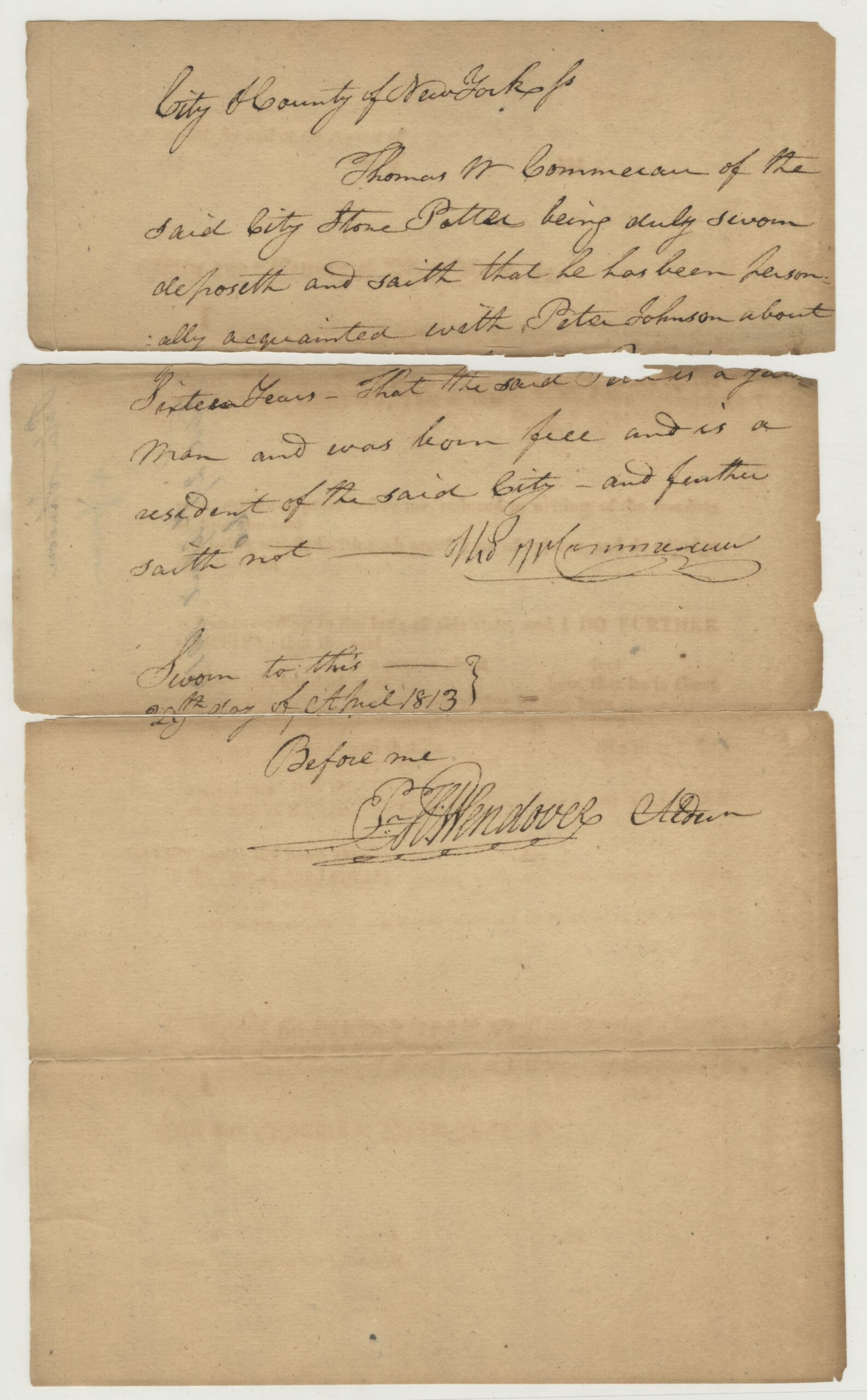

The law required an outside affiant’s statement confirming the free status of the voter and providing his physical description, which subjected the applicant to a potentially humiliating height measurement. Commeraw provided an affidavit for one such certificate, that of Brooklyn-born, twenty-one-year-old Peter Johnson. The original document, in the New-York Historical Society’s collection, includes Commeraw’s statement above his practiced flowing signature, attesting to his literacy and his confidence presenting himself in a white bureaucratic context (Fig. 20).

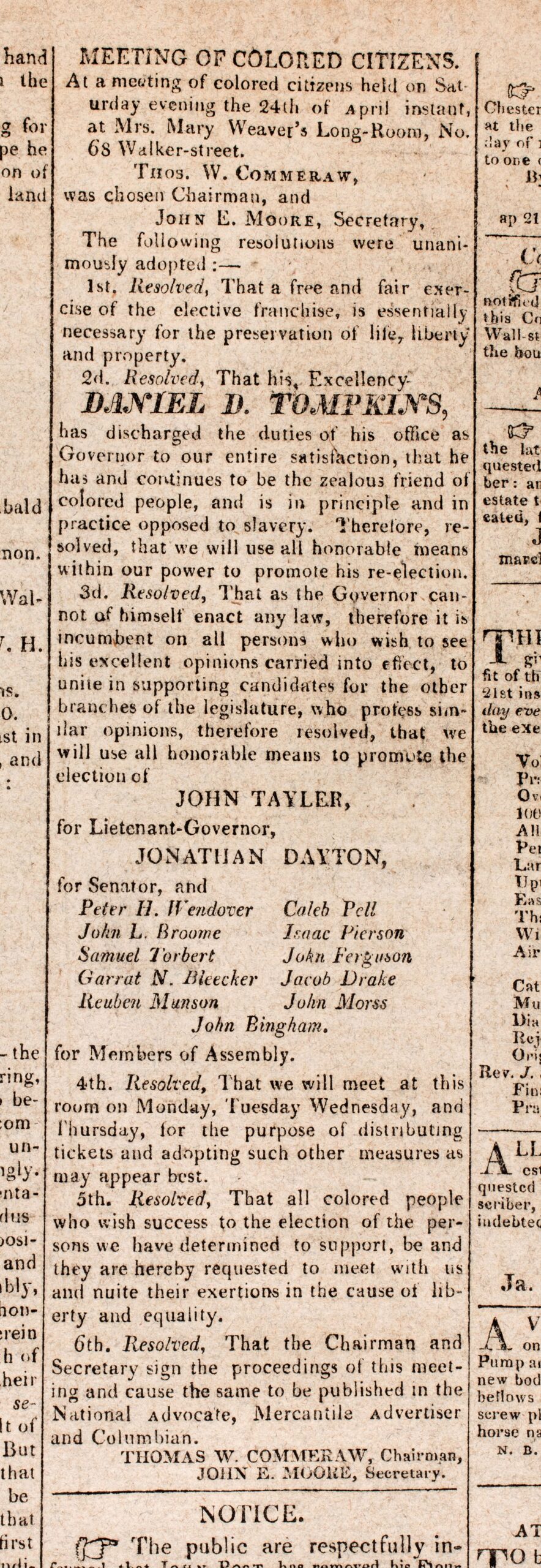

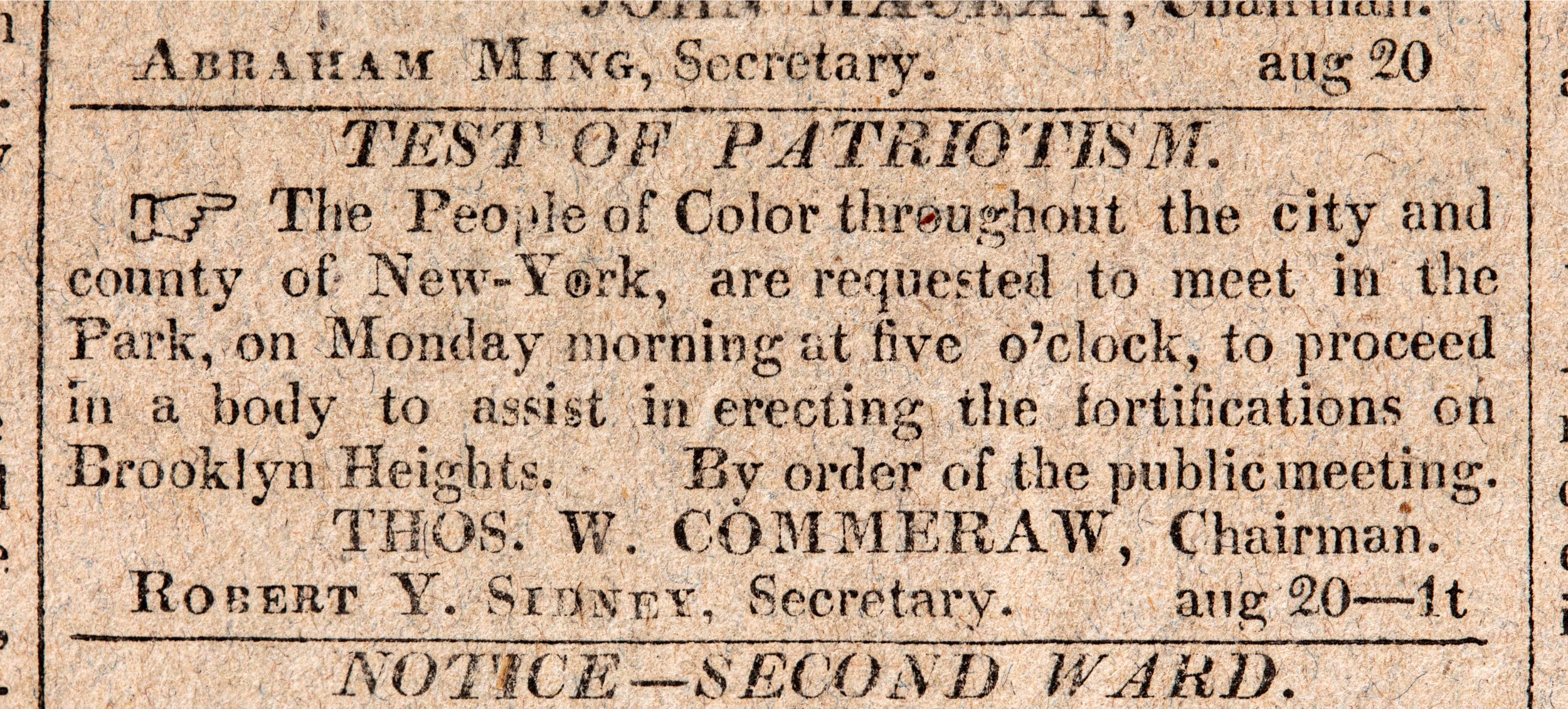

Commeraw’s civic activities continued during a special election in 1813. At a meeting of “colored citizens,” he was chosen as chairman of a committee to re-elect Daniel Tompkins, the Democratic-Republican gubernatorial candidate. The meeting affirmed that Tompkins was “a zealous friend of colored people and is in principle and practice opposed to slavery” (Fig. 18). The following year, as the ongoing War of 1812 threatened to engulf the city, Commeraw again acted as chairman of a committee, this time rallying his fellow Black New Yorkers to help build fortifications at Brooklyn Heights (Fig. 21). This may have been a defensive move to demonstrate the unassailable patriotism of Black New Yorkers, since many Blacks had joined the Loyalists during the Revolution and some feared the new war could precipitate a white backlash.

Commeraw exhorted his brethren to show their patriotism by marching through the city to lend a hand. Nearly a thousand Black men heeded the call to help unite a factionalized city.

Fig. 12. Jar by Commeraw, New York City, c. 1800–1810. Marked “COERLEAR.S/ HOOK” on the front and “N•YORK” on the back. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 10, diameter 8 3⁄4 inches. Collection of the Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Fig. 13.Jug by Commeraw, New York City, c. 1800–1819. Marked “COMMERAW.S/ STONE-WARE/CORLEARS/ HOOK/N•YORK [upside down]” on the front. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt and manganese-iron oxides; height 12, diameter 7 3/4 inches. New-York Historical Society, purchased from Elie Nadelman; Castellano photograph.

The war and its aftermath hit New York’s shipping-based economy hard. As bankruptcies in the city spiked, Commeraw spiraled into debt, losing a series of civil suits over unpaid promissory notes. These IOUs served as credit instruments at a time of limited currency, unstable banking, and lack of access to capital, especially for the less well-connected. At least once, years earlier in 1798, Commeraw had successfully sued a “Gentleman,” an “attornie of the Supreme Court of the Judicature”—certainly a white man—for an unpaid promissory note for the then-considerable sum of $102.50.7 We can imagine that Commeraw’s business model would have necessitated buying clay and costly wood for firing his kiln, while at the same time he offered credit to wholesale customers. When the economy tightened, this undercapitalized credit system quickly toppled.

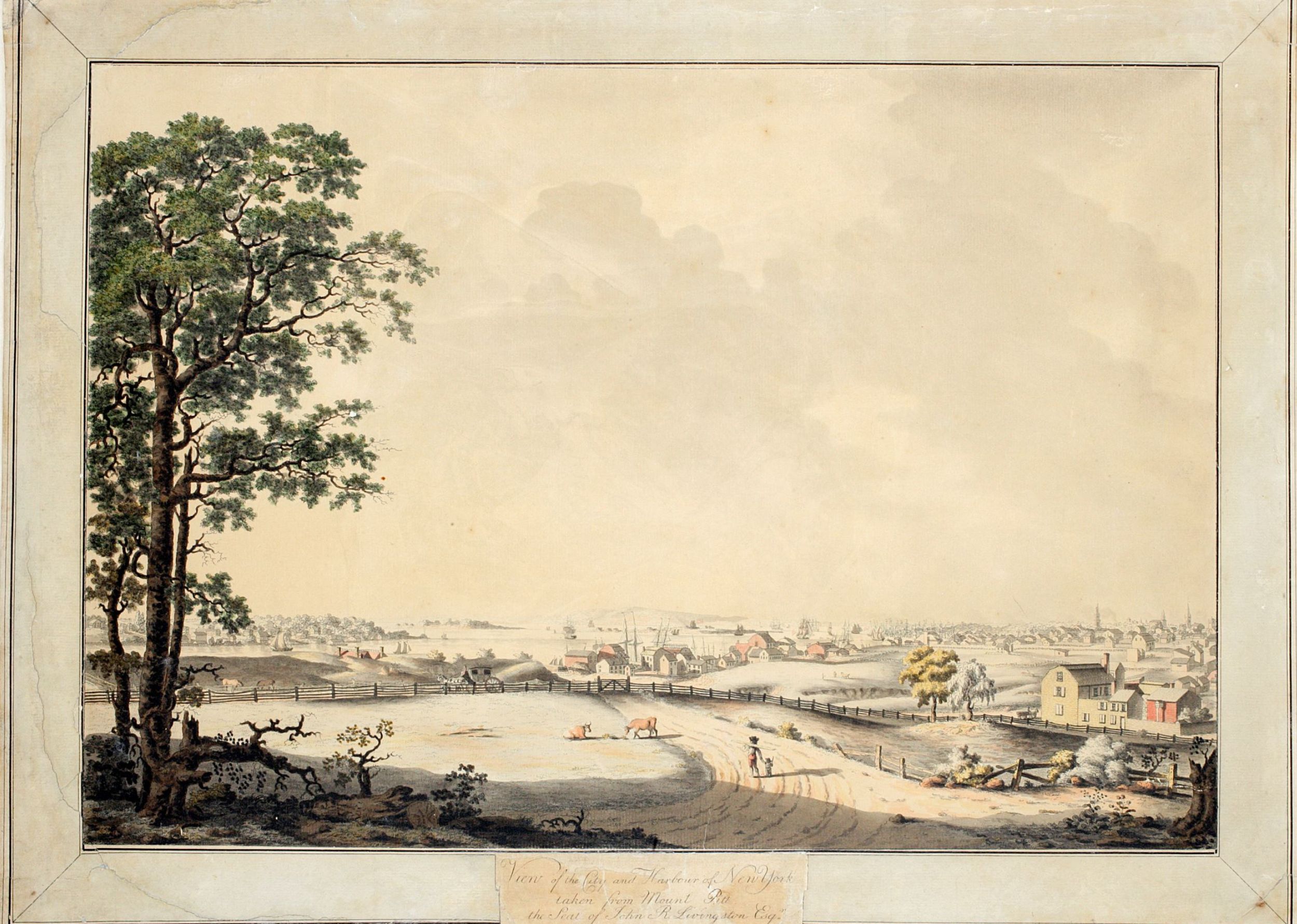

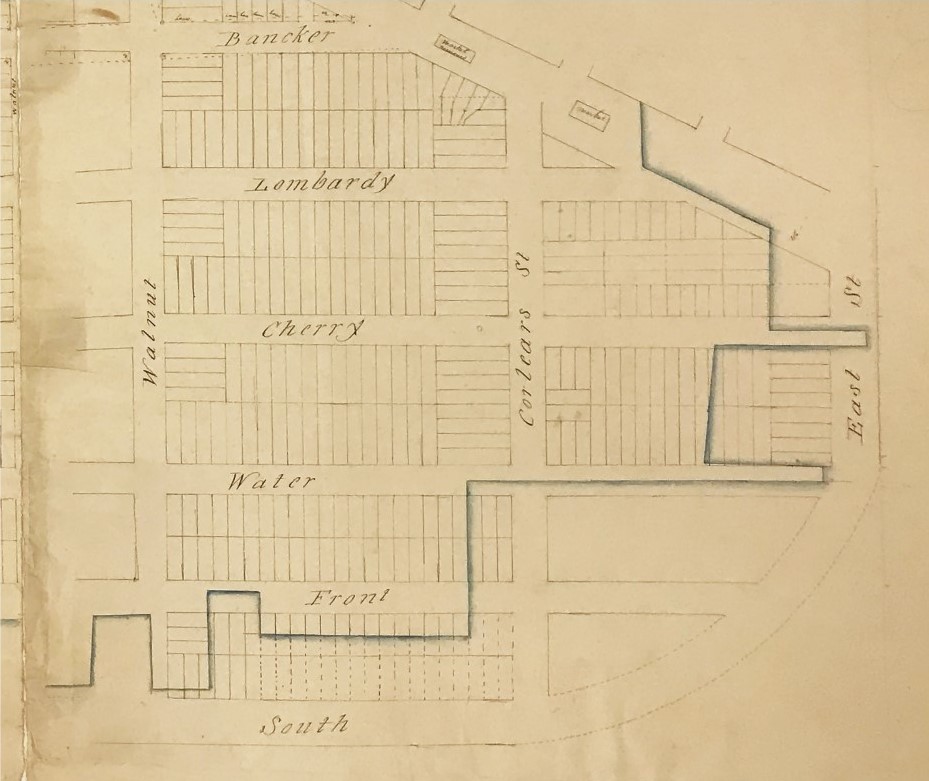

In addition to the economic downturn precipitated by the war, Commeraw’s neighborhood was rapidly transforming with the city’s implementation of the 1811 Mangin-Goerck grid street plan. What had been Commeraw’s near bucolic site on bluffs overlooking the East River in 1797 (Fig. 16) became a grid-bound pair of lots set three blocks back from the water (Fig. 19). The massive infilling of the coastline along the waterfront—cartload by cartload—took years (Fig. 22). One can imagine the disruption such massive land alteration would have had on direct sales from his workshop, with roads impassable, or alternatingly muddy and dusty, and often clogged with stone-filled carts. With diminishing hopes for full citizenship and equality in the land of his birth, and facing increasingly bleak financial prospects, Commeraw joined the first voyage to Africa of the American Colonization Society (ACS). In early February 1820, he and his family and about eighty other settlers embarked for Sierra Leone, where they hoped to found a Black republic in which they would enjoy the full citizenship and dignity that had eluded them in the United States. The shocking lack of planning, general incompetence, racist assumptions, and misapprehension of the cultural forces at work on the ground of the ACS’s white leadership led to predictably tragic results.

Fig. 14. Jug by John Remmey III (1765–after 1831), New York City, c. 1800–1820. Marked “J REMMEY./MANHATTAN-WELLS/ NEW-YORK” on shoulder opposite handle. Salt-glazed stoneware, cobalt oxide; height 11 3/4, diameter 8 inches. New-York Historical Society, purchased from Elie Nadelman; Castellano photograph.

Fig. 15. Three oyster jars attributed to Commeraw, New York City, c. 1800–1805. Stamped, left to right: “G.W. AND Co No 202/WARTER STREET/ N•YORK”; “DANIEL/JOHNSON. No 24/ LUMBER STREET/NEW YORK”; and “D. J. AND. Co No24/ LUMBER STREET/ N•YORK”. Salt-glazed stoneware; height of tallest 8 1⁄4, diameter 4 inches. Collection of Christopher Pickerell; photograph by Christopher Pickerell.

Fig. 16. View of the City and Harbour of New York taken from Mount Pitt, the seat of John R. Livingston, Esq. by Charles Balthazar Julien Fevret de Saint-Mémin (1770–1852), New York, 1796. Hand-colored etching, 16 1/2 by 21 1/2 inches. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

As the seasonal rains arrived, Commeraw’s young wife and niece died of fever; within the first several months, about one quarter of the settlers and all the white agents had died. Their hopeful experiment rapidly devolved into a struggle for survival. Commeraw returned to Baltimore with his remaining family in 1822 and died the following year. Among other archival materials concerning Commeraw’s emigration, Crafting Freedom features personal accounts published by members of the expedition along with two letters by Commeraw that were widely published in American newspapers.

Commeraw created surpassingly beautiful and useful objects in the context of enduring slavery.8 Though the end of slavery in New York was in sight, racialized violence, kidnapping, derision, and the stripping of freemen’s rights were looming realities—more entrenched by the time of his departure for Africa than in 1797, when he had established his independent workshop. His achievement as an artist, palpable in the pots on display in Crafting Freedom, is thus even more remarkable. His courageous endeavors as an entrepreneur, community leader, abolitionist, and head of a family, evident in the archival materials on view, match his exceptional artistic accomplishments and testify to his magnanimity and fortitude.9

Fig. 17. Detail of Henry Sipkins, An Oration on the Abolition of the Slave Trade (New York: John C. Totten, 1809), showing Commeraw leading, singing, and composing hymns. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 18. “Meeting of Colored Citizens” notice in National Advocate, New York, April 27, 1813. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 19. Detail of A Map of the Seventh Ward of the City of New York by John Randel Jr., New York, 1820. Ink and watercolor on paper, 23 1/4 by 61 3/4 inches overall. Commeraw’s two lots were between Cherry and Lombardy. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 20. Certificate of Freedom for Peter Johnson, New York, 1813. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 21. “Test of Patriotism” in Commercial Advertiser, New York, August 20, 1814. New-York Historical Society, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library.

Fig. 22. Detail of Sanitary and topographical map of the city and island of New York by Egbert L. Viele, New York, 1865. Lithograph, 18 by 63 inches overall (image). The pink areas indicate infill. New York Public Library.

Crafting Freedom runs from January 27 to May 28 at the New-York Historical Society and travels to the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, from June 24 to September 24. Curated by NYHS director Margi Hofer, the author, and Mellon postdoctoral fellow Allison Robinson, the exhibition features twenty-two vessels produced in Commeraw’s Corlears Hook workshop and fourteen made in the shops of his competitors.

1 A. Brandt Zipp, Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner (Sparks, MD: Crocker Farm, 2022). 2 I am indebted to Leslie M. Harris for this insight. 3 The conservation of this jar, and that of the jug shown in Fig. 13, was supported through the NYSCA/GHHN Conservation Treatment Grant Program administered by Greater Hudson Heritage Network. This program is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. Additional support is provided from the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation. 4 Republican Crisis, Albany, New York, February 23, 1807, regarding a proposed “African society of the city of New-York, for improvement.” 5 Whether he wrote only the lyrics or both the music and lyrics is unclear. There is evidence of similar musical and lyrical authorship in two hymns written by separate members of the New York African Society for Mutual Relief in 1810. 6 These restrictions were further tightened in 1815 and again in 1821 when property requirements became so strict that very few Black men could vote. At the same time, almost all white men were granted the franchise. While propertied free Black men such as Commeraw could generally vote in New York after the Revolution, they were barred from jury service and the militia, the other standard markers of male citizenship. 7 Thomas W. Commeraw v. John McNeill, New York State Supreme Court, December 13, 1798, February 28, 1799, Ref P-10, B10, slip No. 959-AA, New York State Archives, Albany. 8Although the proportion of enslaved to free Black New Yorkers diminished rapidly during Commeraw’s lifetime, slavery was only finally abolished in the state in 1827. 9 Cornel West has offered this framing for understanding the endurance of hope in the face of oppression in Black culture. See Christopher Lydon’s interview with West and David Bromwich, “Where Shall Wisdom Be Found,” June 20, 2022, at radioopensource.org.

MARK SHAPIRO, a potter, edited A Chosen Path, the Ceramic Art of Karen Karnes (UNC Press, 2010). His interest in Commeraw began during a Smithsonian Artist Residency Fellowship at the National Museum of American History.