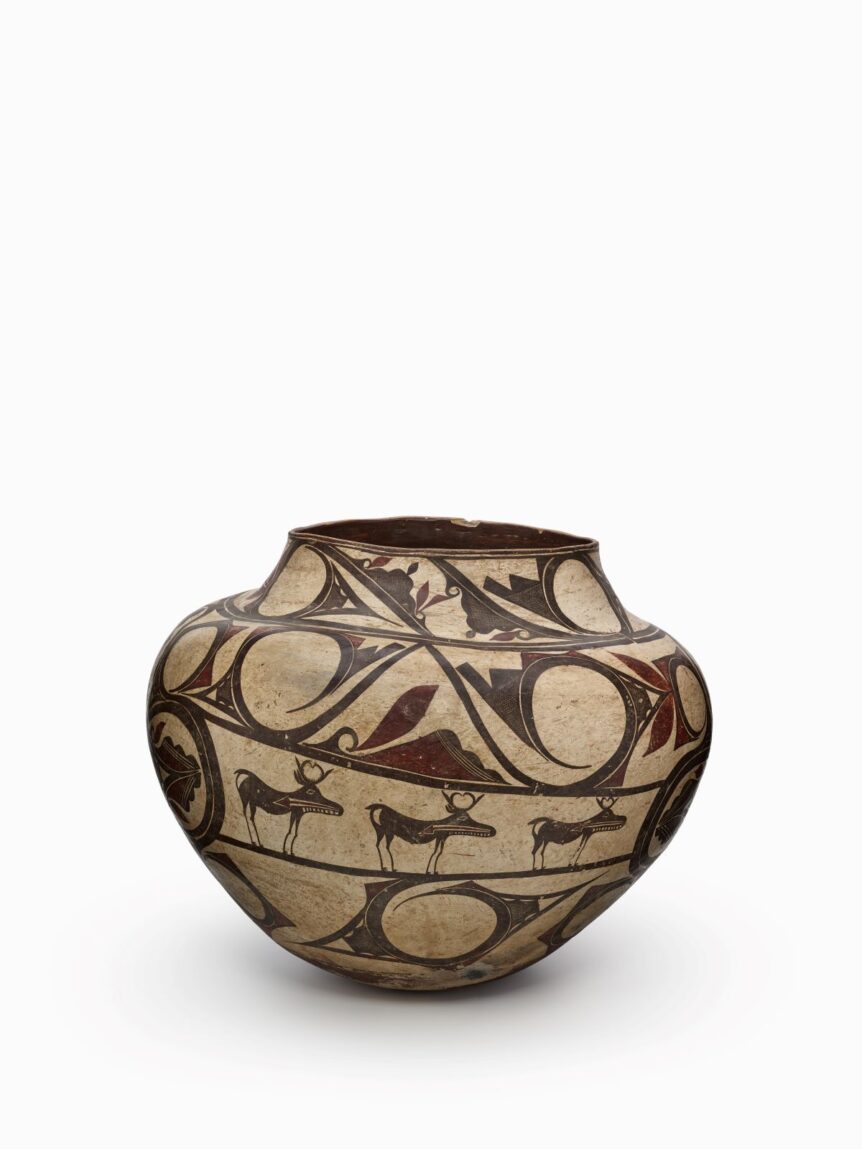

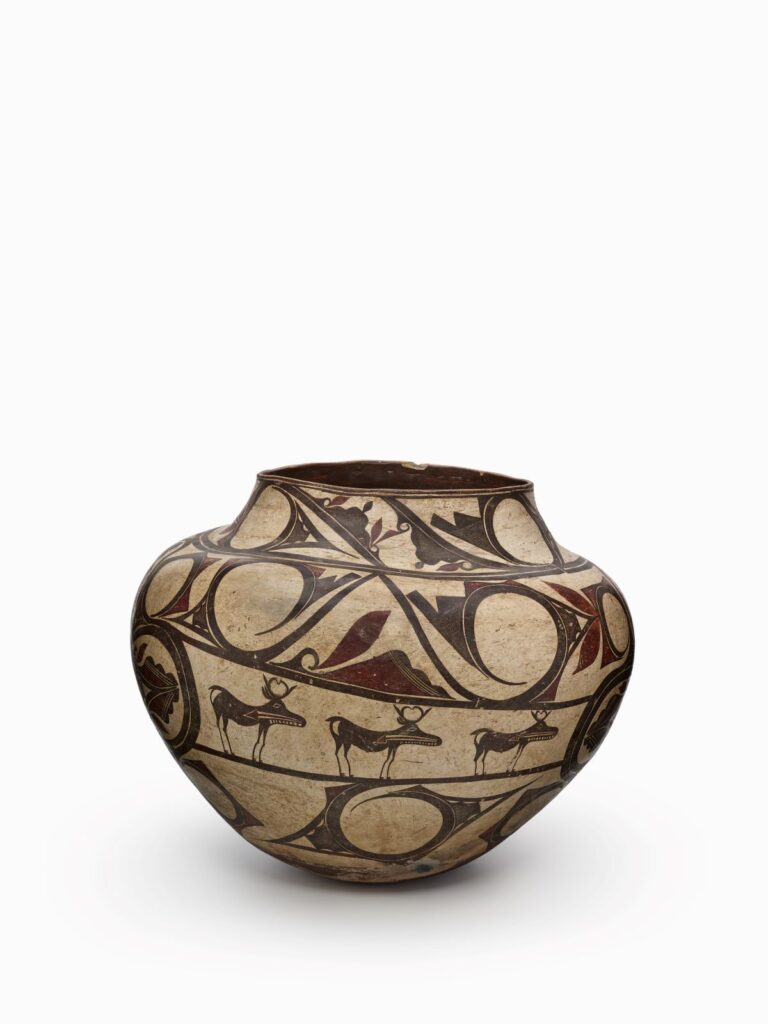

“There are several ollas attributed to Arroh-a-och in museums across the country. I use the gender pronouns ‘she,’ ‘her,’ and ‘hers’ when referring to Arroh-a-och. She was a two spirit. This is an alternative gender in various Native American cultures. At Laguna, a transgender female, or k’ukwi-mu, wore women’s attire and performed tasks traditionally assumed by women, such as grinding corn and making pottery. . . .The excellence of her work distinguishes Arroh-a-och as one of the most talented potters at Laguna Pueblo.”

Max Early (Laguna Pueblo)

Here and elsewhere, quotations are from the individual who selected the object under discussion for inclusion in the traveling exhibition Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery.

A water jar made about 1720 by a member of the Zuni people sums up the occasionally fraught history of archaeological research and the preservation movement in the American Southwest. Damaged at a 1922 dinner party convened by members of the Anglo elite, who long dominated northern New Mexico’s legacy cultural institutions, and then repaired, the jar that same year became the first artifact to enter the now more than twelve thousand–object collection of what became the Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe. Along with masterworks from the collection of the Vilcek Foundation, selections from SAR’s holdings form the bulk of Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery, a traveling exhibition making its current stop in New York City.

Founded in 1907 as the School of American Archaeology, SAR is today a far more nimble and socially responsive place than it was a century ago, when Ivy League–educated men dominated the field. “Our elevator pitch needs a fifty-story building,” acknowledges SAR president Michael F. Brown, the cultural anthropologist presiding over the institution’s ambitious set of programs in the arts and social sciences, which range from residencies for artists and scholars to symposiums and an academic press.

Activities at SAR unfold on the grounds of what was once an estate known as El Delirio—the home of arts patrons Martha Root White and Amelia Elizabeth White, sisters whose terraced gardens and swimming pool, a Santa Fe first, beckoned the stylish set. Amelia Elizabeth was among the first to promote Native American art in Manhattan, opening a shop for Indian arts and crafts on Madison Avenue in 1922 and helping to organize the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts at New York’s Grand Central Galleries in 1931.

“Pictorially and materially, both pots embody growth and the renewal of life—gentle reminders of the beauty and fragility of the natural world on which we humans depend.”

Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha)

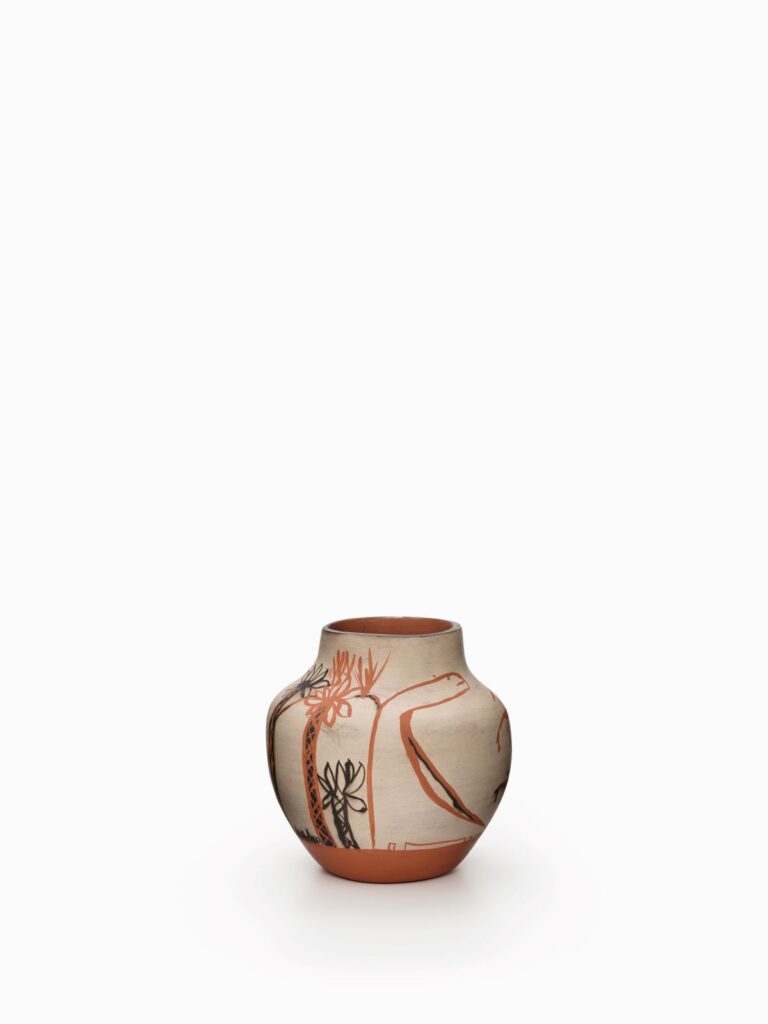

“Avanyu (serpent) is often portrayed on Santa Clara pottery, symbolizing water. Avanyu may represent heavy flooding after a torrential storm and also the gentle, soft flow of a river or stream.”

Jason Garcia (Tewa/Santa Clara Pueblo)

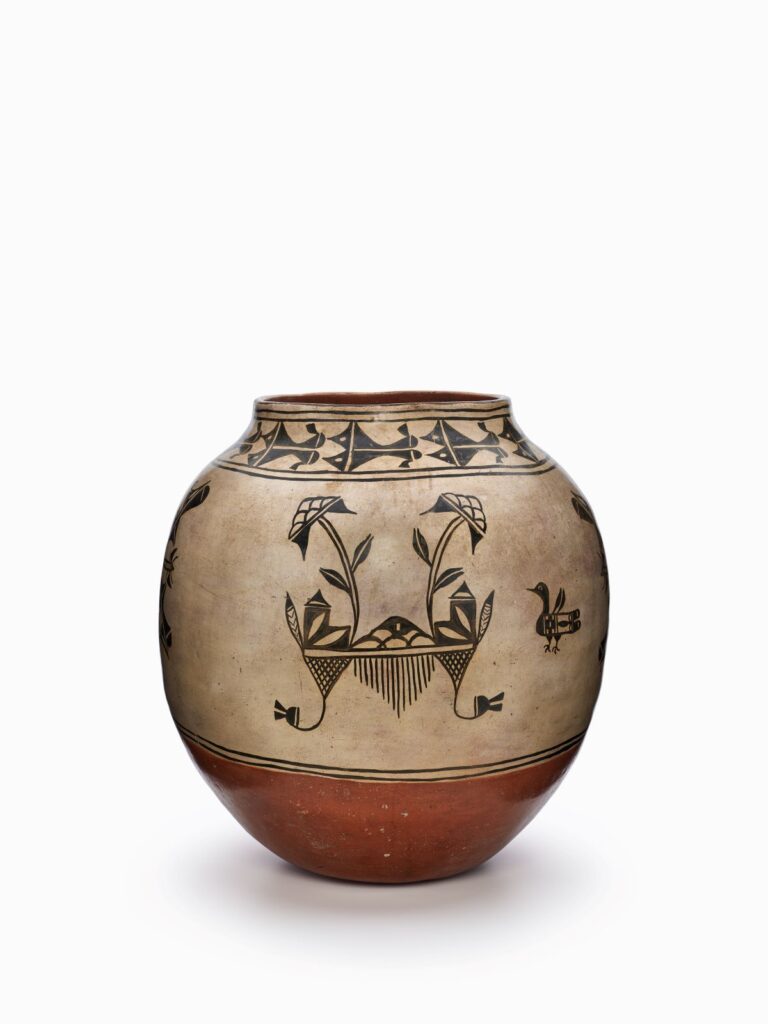

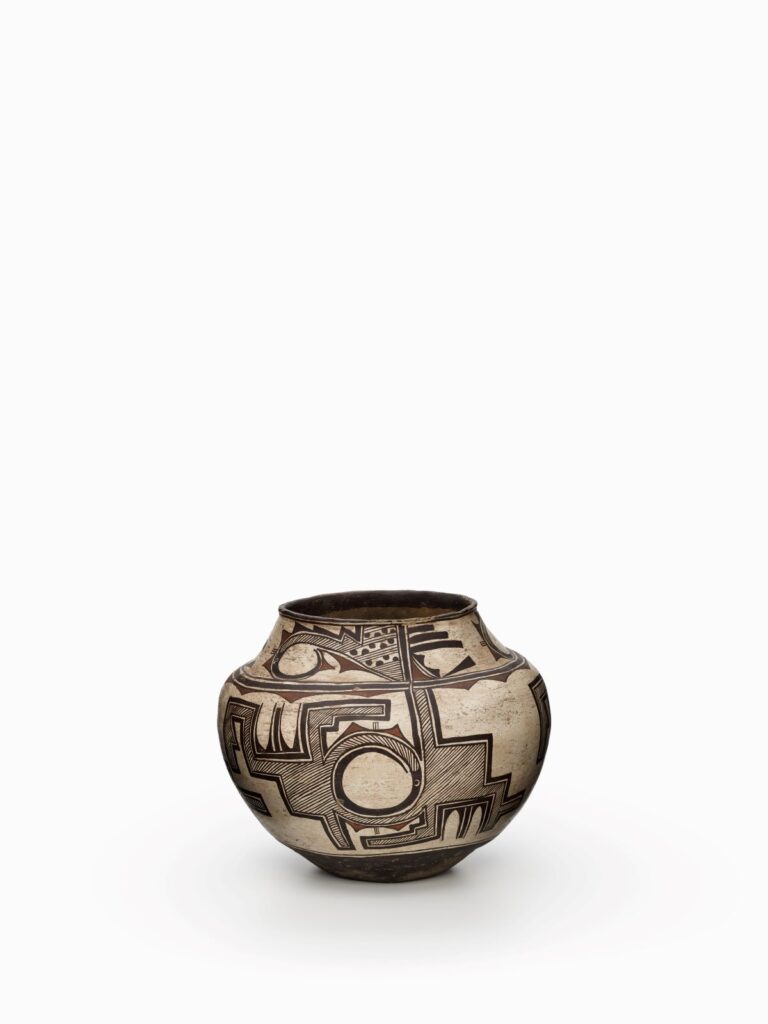

“The jar had previously passed through hands that believed its decoration was of a fish, an ‘abstract fish’ at that. Yet through talks with Acoma relatives and simple research, I found out that it is a thunderbird—a design its ancestors have been depicting and developing for centuries. Not a fish. I state again: Pueblo voices should always be prioritized when one talks about, interprets, and exhibits Pueblo pottery.”

Erin Monique Grant (Colorado River Indian Tribes)

Many observers now take a nuanced view of Santa Fe’s history, softening their embrace of the city’s colonial past while acknowledging the truth of settler usurpation of the land that Tewa-speaking people call O’gah’poh geh Owingeh—a name that translates as White Shell Water Place. IARC’s purpose has also shifted over time, from managing a premier collection of southwestern Native American art on behalf of a clique of scholars and collectors, to preserving and interpreting artifacts with the participation of the community that made the work. As a research collection, IARC’s holdings have long been on view by appointment only. Two handsome open-storage vaults house baskets, jewelry, katsinam (carved figures of spirit beings), paintings, and textiles, plus more than 4,750 pieces of pottery, from ancient to contemporary.

Change at IARC accelerated under the leadership of its current director, Elysia Poon, and two predecessors, Brian D. Vallo (Acoma Pueblo) and Cynthia Chavez Lamar (San Felipe Pueblo/Hopi/Tewa/Diné), the latter now director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The trio helped draft IARC’s Guidelines for Collaboration, which—along with the Standards for Museums with Native American Collections and the Indigenous Collections Care Guide, all detailed on the SAR website—have elevated SAR’s reputation as a leader in contemporary approaches to managing institutional collections of Native American art. “It’s a lesson in what a small institution can do by bringing people from big institutions together to formulate policies,” Brown says.

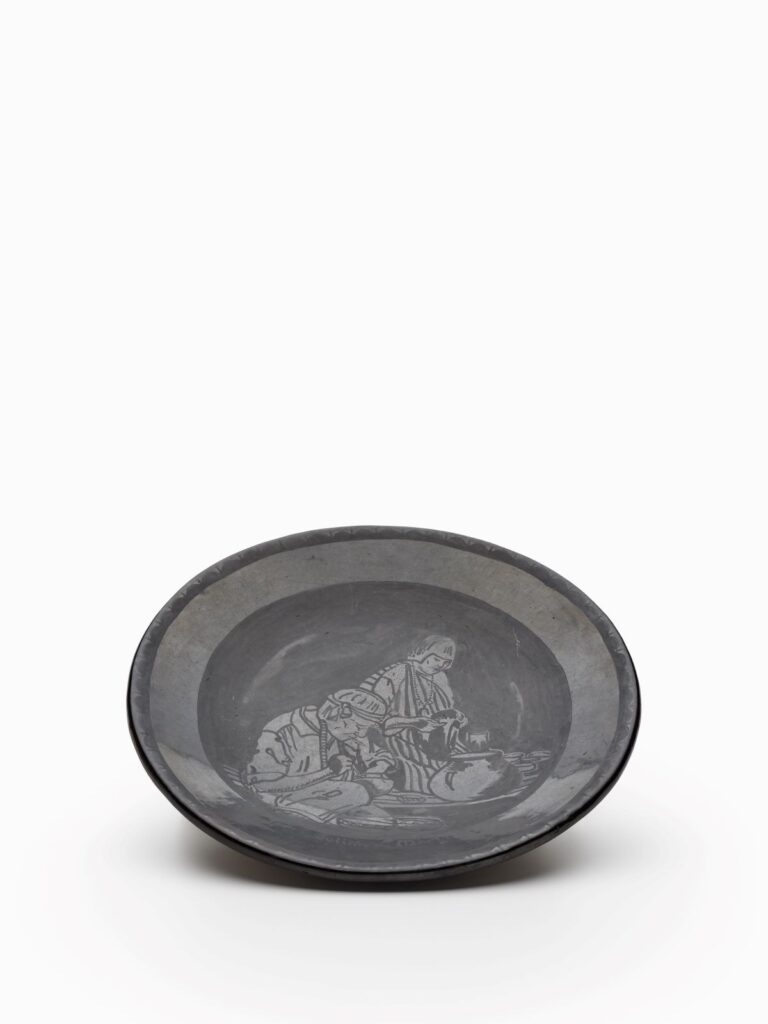

“The piece was Maria’s signature black-on-black pottery—but it was the etched ‘selfie’ that continued to intrigue. At one point while studying the plate in my white gloves, I became wrapped up in the knowledge that I was holding and touching the work of the great clay genius Maria Martinez. It was a surreal and powerful moment for me.”

L. Stephine “Steph” Poston (Sandia Pueblo)

“Do not forget: Lonnie [Vigil] built his monumental vessel on his kitchen table. Who does that? A master artist with passion, that’s who.”

Nora Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara)

“The mono (Spanish for monkey) is essentially a Cochiti perspective on the people and culture of the outside world, and Cochiti artists create these figurines to sell to those people alongside traditional polychrome pottery. The monos represent the curiosity of the artists who make them, and also their fear, humor, trepidation, and financial need.”

Mateo Romero (Cochiti Pueblo)

IARC’s first traveling exhibition since its founding a century ago, Grounded in Clay adheres to a foremost tenet of the guidelines: engage communities of origin as partners in project development and execution. Poon notes: “Developing relationships with descendant communities is not new. A good example of an early community-driven project is the evolving, semi-permanent installation Here, Now and Always, which first opened at Santa Fe’s Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC) in 1997. What is new is offering Pueblo voices as a group curatorial expression and raising awareness nationally by traveling Grounded in Clay to other museums and regions.”

The project’s exuberant heart is the sixty-eight-member Pueblo Pottery Collective. First convened in 2019 by Poon, the group includes potters and other artists, as well as writers, poets, educators, community leaders, and museum professionals. Most are from twenty-two Pueblo communities, nineteen of which are in New Mexico. Poon invited each participant to act as a curator and select one or two pieces of pottery for Grounded in Clay. Expressed in essay, verse, and video, the curators’ observations about the ceramics weave through the show, its accompanying catalogue, and a documentary film produced by New Mexico PBS.

Deep, soulful, and celebratory, Grounded in Clay is a listening tour—Pueblo community curators listening to the modeled, painted, and fired earth that many members regard as spiritually animated, while visitors in turn listen to Pueblo voices. An inability to hear prevents us from seeing, the presentation seems to say, wisdom with broad meaning for North America’s tortured past and tumultuous present.

Pueblo voices are not monolithic, as we are reminded by a text panel thanking visitors to the show in seven languages and several dialects spoken by the curators. Neither are Pueblo stories, which defy strict categorization but together form a rich, oral tradition. “Make your stories worth telling. Those are the ones that live the longest. They bring us back home,” writes Monyssha Rose Trujillo (Cochiti/Santa Clara/Laguna/Jicarilla Pueblos/Diné), who chose a clay figure of a storyteller, a subject popularized by Cochiti Pueblo potters.

In New York, Grounded in Clay is on view in two locations: at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and, by appointment, at the Vilcek Foundation town house on East 70th Street. At the Met, the show follows the powerful exhibition Water Memories in what the museum informally calls Wolf North, a rotational space that Patricia Marroquin Norby, the museum’s associate curator of Native American art, uses for imaginative explorations of issues and themes suggested by the adjacent long-term installation of Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection. Norby sees the two temporary exhibitions as a continuum. The elements—earth, wind, fire, and water—are intrinsic to Pueblo art and belief. As community curator Tony R. Chavarria (Santa Clara Pueblo) reminds us, “Through humble elements of the earth, gifts of the Clay Mother, we are connected.”

Norby has made the space a welcome spot for contemporary Native expression, newly vibrant on the international stage thanks to institutions such as Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), a fulcrum for Native arts education since 1962, and an array of exhibitions, among them the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, a retrospective look at the work of another lauded New Mexican artist of Indigenous descent, on view in New York through August 13.

In the Met’s iteration of Grounded in Clay, Norby introduces the work of four contemporary Pueblo artists known for mediums other than clay. By doing so, she creates tension between the traditionalism of Pueblo pottery, remarkably constant over the last millennium, and new art that moves assertively between two worlds, Native and non-, synthesizing both to project portraits of indigeneity defiantly at odds with old stereotypes.

Elysia Poon, director of the Indian Arts Research Center and co-organizer of Grounded in Clay, chose this circa 1720 Zuni water jar as a way of honoring the memory of her late friend and colleague Tim Edaakie (Zuni Pueblo), a member of the Pueblo Pottery Collective and a 2019 SAR Native Artist Fellow.

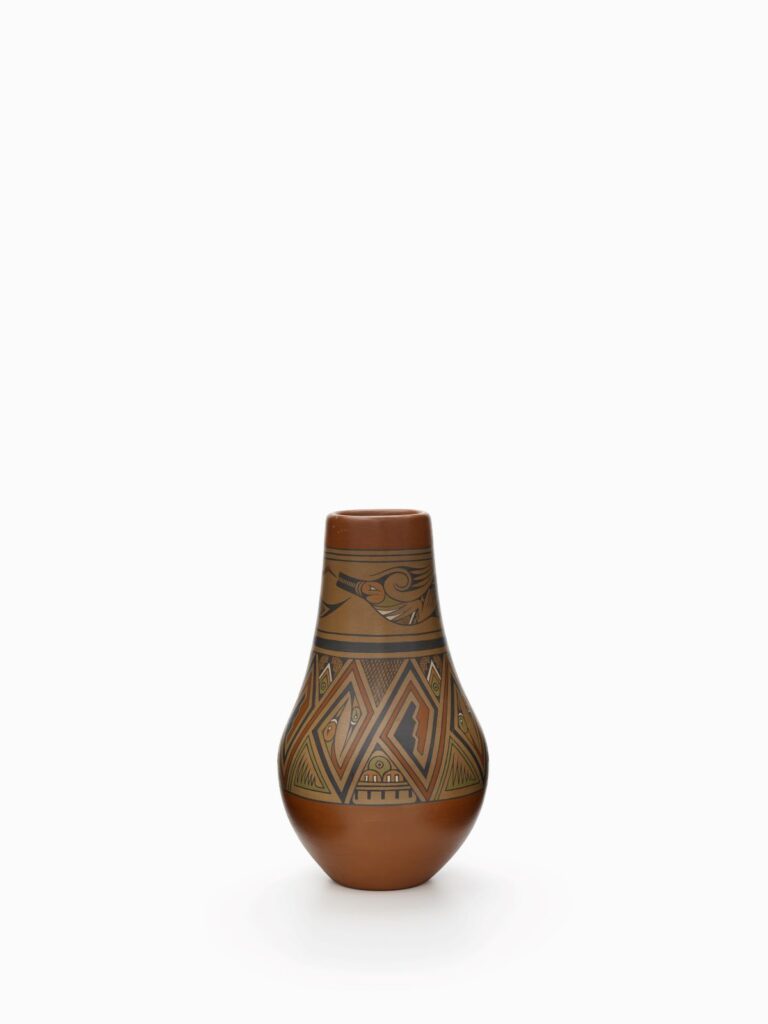

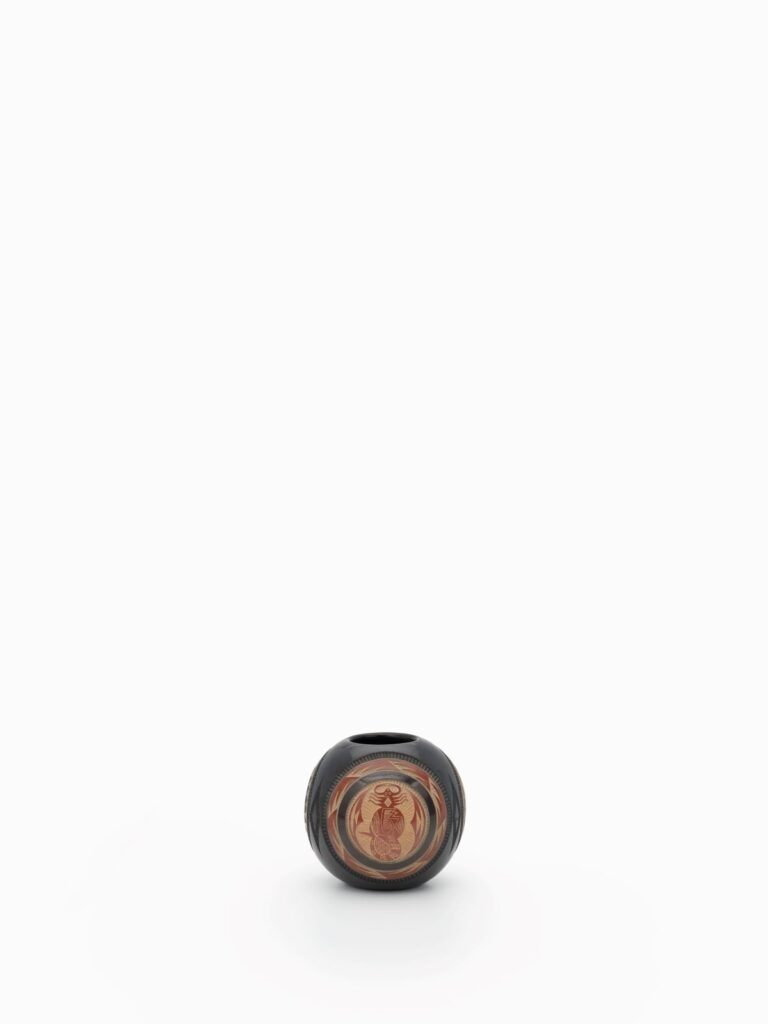

“I chose this pot because it represents a transition from traditional Pueblo pottery to more contemporary forms in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Works by Popovi Da and, shortly thereafter, Joseph Lonewolf and Tony Da were influential in that shift. Their vessels inspired many emerging Native artists, me included, to develop new techniques in not just pottery and design, but also Native art forms as a whole.”

Cliff Fragua (Jemez Pueblo)

Murals by De Haven Solimon Chaffins (Laguna/Zuni) and Mallery Quetawki (Zuni) are the first things visitors to the Met see. Environmental themes, especially the toxic toll of uranium mining on or near Native land, interest both artists, who deftly manipulate Pueblo motifs and patterns across fields of luminous color. Trained in science and the arts and keenly aware of her role as a communicator, Quetawki says, “Art creates a common language and we artists are a vital part of storytelling and record-keeping for our cultures.”

Farther along in the Met show, a community table set with pottery suggests the medium’s ubiquity in Pueblo life, where it is used for storing, cooking, and serving food and water. “Even today, when people visit, we offer them a dipper, a glass, or a bottle of water. By keeping this custom and the knowledge behind it alive, we honor the water and all our ancestors and grandmothers,” writes community curator Diane Bird (Kewa/Santo Domingo Pueblo).

The gallery’s largest wall is reserved for a newly commissioned diptych by Michael Namingha (Hopi/Ohkay Owingeh) and Mateo Romero (Cochiti Pueblo). Working in contrasting styles but joined by a shared keynote of color, the two award-winning artists—both members of the Pueblo Pottery Collective—contemplate the meanings of landscape for Pueblo people.

A descendant of the great Hopi potter Nampeyo (c. 1860–1942), Namingha has in recent years experimented with photographs of distant landscapes, sometimes captured via drone or Google Earth and mounted on shaped acrylic. These irregular forms push the limits of two-dimensional perspective and, in the abstract, suggest pottery fragments collaged together—a faint echo of an approach to patternmaking employed by Namingha’s grandmother Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo (Tewa/Hopi) (1928–2019), whose 1980 jar he chose for Grounded in Clay.

“The artist was just twelve years old when he created this pot. . . . We rarely see children’s artwork in museum collections, but it is evidence of the ongoing cultural and artistic traditions of our communities.”

Felicia Garcia (Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians/Samala Chumash)

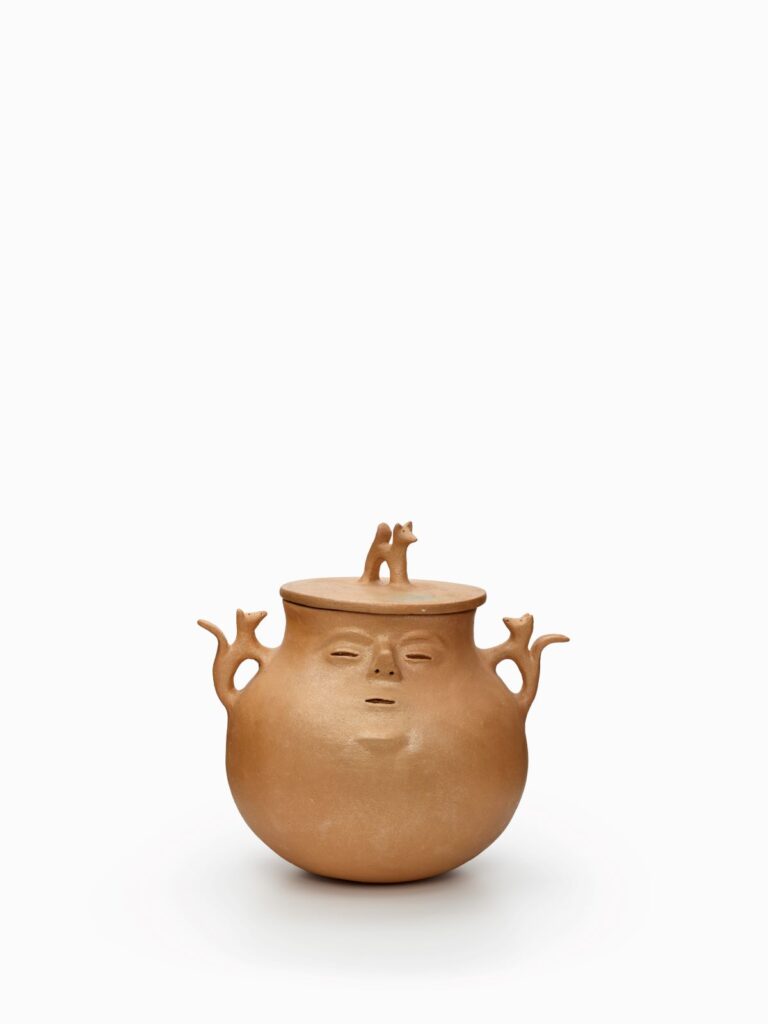

“My grandmother, Lorencita Pino, worked with this orange clay and often incorporated faces and animals into her designs. The handles on this vessel are foxes, but they have stripes on their tails like chipmunks; animals that live in our communities are a part of everyday life and prayer.”

Mark Mitchell (Tesuque Pueblo)

Cool and remote, Namingha’s meditative images are as much about art-making as about landscape. For the Met, he created a photo silkscreen on a shaped, wooden panel, seeking advice from master printer Luther Davis on printing with a combination of ink and sand, the latter gathered from clay beds visited by his forebears. The work incorporates a double-printed view of Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, a place of profound spiritual importance for Hopi people, but one lately menaced by environmental degradation. Namingha says, “Grounded in Clay is about looking at our heritage—our design heritage, our family heritage—and the vessels our ancestors created. In my case, it’s also about looking for clues within my own artistic practice and how they link me to my past. Chaco is a place where we all come from.”

“Pueblo people are sublimated in the landscape, not apart from it, as observers of a natural sublime,” says Romero, whose loose, expressionistic landscapes are sometimes inhabited by enigmatic figures. “The Tewa have a word for it, poeh-ha, which means breath of life. I’m trying to capture a piece of that connection to the landscape—the energy, the movement. My landscapes are not invented or remembered; they are specific spaces. I use preexisting indigenous names for places and spaces. Language creates meaning.”

If one notion describes Grounded in Clay it is the extent to which Pueblo pottery is the collective artistic expression of people who care for one another and are joined by traditions that, against the odds, have survived history’s adverse currents. Only spiritual conviction can explain such durability. As Albert Alvidrez (Ysleta del Sur Pueblo), one of the exhibition’s curators, tells us: “Our journey teaches us to be patient, that we must rest and let time travel, but when we emerge, we go forward with enthusiasm, grace, and focus. Today, I join my clay brothers and sisters gathered to reflect on our journey, share our song, and sow seeds of hope and encouragement for all those who encounter us. Our pottery voices remain resilient and continue to be heard.”

“I love walking the same paths as those walked by my ancestors, following their footsteps, feeling their presence, seeing pottery, and studying drawings. I introduce myself to my ancestors, tell them of my intentions, leave my offering, and thank the ancient ones for walking with me and showing me their home. I experience a place of gathering for our people, and feel and understand the environment and its elements. In these surroundings, I always feel a sense of renewal and balance. This is reflected in my re-creations of ancestral pottery.”

Lorraine Gala Lewis (Laguna, Taos, Hopi Pueblos)

Changing Minds, One Pot at a Time

The day I met Brian D. Vallo at Downtown Subscription, a coffee bar and newsstand near Canyon Road in Santa Fe’s historic arts district, the former Acoma Pueblo governor and current trustee of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian was in a celebratory mood. Congress had days earlier passed the STOP Act, legislation barring the exportation of Native American sacred objects and imposing increased penalties for the theft and trafficking of Native American cultural patrimony.

“We have been working on this since 2016,” says Vallo, for whom art and advocacy have long been joined. A past director of Santa Fe’s Indian Arts Research Center, Vallo—a consultant whose clients include the Vilcek Foundation in New York, the Field Museum in Chicago, the de Young Museum in San Francisco, the Heard Museum in Phoenix, and the Shelburne Museum in Vermont—helped write the School for Advanced Research’s Guidelines for Collaboration, a resource for institutions seeking partnerships with the Native communities that are the sources of artworks.

A joyful expression of SAR principles, Grounded in Clay evolved from parallel conversations that Vallo, a community advisor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s installation Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, had with Sylvia Yount, the curator in charge of the Met’s American Wing, and with Vilcek Foundation president Rick Kinsel, long involved with helping collectors Jan T. Vilcek and Marica Vilcek shape their holdings of Pueblo pottery. As Kinsel explains, “For years, the Vilceks and I considered how we might create an exhibition that would allow us to share items in our collection with the public. And from the start, I was looking for a partner in the endeavor—a partner institution to work with who could establish and support meaningful connections with Pueblo artists and cultural leaders. We identified the School for Advanced Research and Brian Vallo as project partners early on.”

Of the more than one hundred ceramics featured in the initial iteration of Grounded in Clay, twenty-four belong to the Vilceks or their foundation. Emily Schuchardt Navratil, the foundation’s curator, says the couple became interested in Pueblo pottery, one of four major focuses of their collection, after first visiting Santa Fe in 1988 and returning for twenty-two consecutive summers. The foundation’s exceptional trove now numbers just over fifty pots, bowls, and jars dating from around 1100–1300 to the early twentieth century.

In Manhattan, slightly more than half the pieces in the original Santa Fe presentation of Grounded in Clay, or sixty-one ceramics in all, are on view by appointment in the Vilcek Foundation’s town house galleries at 21 East 70th Street. Himself a member of the Pueblo Pottery Collective, Vallo—who co-curated the section on view at the Vilcek Foundation—chose two Acoma pieces for the exhibition. He first encountered one of the ceramics, a circa 1880 storage jar decorated with stylized clouds, rainfall, and cornfields, at a San Francisco auction house in 2006 and saw it again on a 2019 visit to the Vilcek Foundation. He relates, “Having the privilege of holding the jar, connecting with its form and construction, I spoke to it in my Acoma language: I introduced myself, shared words of admiration, and gave thanks for the opportunity to meet again.”

Through its support of the exhibition, catalogue, and associated efforts, the Vilcek Foundation amplified Pueblo voices for a dramatically expanded audience nationwide. “The Vilcek Foundation recognizes the challenges that indigenous communities in the United States and around the globe have experienced as a result of colonization and imperialism,” Kinsel says. “With Grounded in Clay, we wanted to create an exhibition that not only showcases historic pieces of Pueblo pottery from the Vilcek Collection but celebrates the living cultures and artistic traditions of Native American people and communities in the United States.” – L. B.

Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from July 14, 2023 to June 4, 2024, and at the Vilcek Foundation, where it may be viewed by appointment, from July 13 to June 2, 2024. (To schedule a tour, visit https://vilcek.co/gic-tour). The exhibition will subsequently travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Saint Louis Art Museum.