Found materials have been intrinsic to Joan Parcher’s life and work since she was a child growing up in Oakmont, a frayed former steel town turned Environmental Protection Agency cleanup site on the east side of the Allegheny River, near Pittsburgh. The granddaughter of Ukrainian immigrants—her paternal grandfather worked for the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company—Parcher remembers picking bits of glass out of the dirt and gathering wire, metal piping, and soapstone from a dump to fashion objects. “In early spring nearby Ford City glittered with glass,” says Parcher, who trained as a jeweler but found a dual calling as an artist and aficionado of antique furniture hardware.

Parcher studied drawing during Saturday morning sessions at the Carnegie Museum of Art, her first formal exposure to art. She did a bit of silversmithing in high school and remembers trekking with friends along the railroad tracks to the neighboring town of Verona, home of The Store, a crafts gallery launched by Betty Raphael (1920–1998), the visionary founder of Pittsburgh’s first gallery for modern art, Outlines, and what is now the not-for-profit exhibition space Contemporary Craft.

“We were just kids in cut-offs and dirty sneakers, but The Store made us feel welcome. The manager took jewelry out of cases for us to see and talked to us about the work,” she recalls. Stimulated by the experience, she enrolled in Kent State’s BFA program in jewelry, metals, and enameling. Her five instructors—“each different but all great”—included enamelist Mel Someroski (1932–1995) and the jeweler Mary Ann Scherr (1921–2016). Parcher continued her studies at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where she has lived since 1984.

In a graceful neighborhood not far from RISD, Parcher lives with her husband, Ralph, in what she calls her “jewelry cave,” a mixeduse space additionally serving as atelier for her creative work and collections storage. Tagged, bagged, and stacked in bins is her thirty-thousand-plus-piece assemblage of antique furniture hardware. It all but fills her small studio and spills into the dining room, living room, bedroom, attic, and basement. Tools for cutting, chasing, and stamping metal clutter her workbench. Period trade directories and catalogues, some extensively annotated in the artist’s tidy hand, crowd a nearby table.

“Honestly, it’s gotten out of control,” Parcher says. This small, youthful-looking woman with a modest, direct manner has parlayed her affinity for metals into an eclectic professional sideline evaluating, repairing, replacing, and replicating antique hardware. Parcher salvages nuts, screws, pins, nails, tacks, bolts, locks, handles, knobs, plates, escutcheons, rings, rosettes, finials, and casters used on American furniture. The pieces, primarily made of iron and brass, date from around 1680 to 1840. “Aesthetic movement hardware is getting really popular, so if I find it, I’ll save it. I do some modernism and have some Paul McCobb and George Nelson stuff somewhere,” she says.

The collector embarked on her mission to preserve old hardware in 2004. “A little antiques store in Warren, Rhode Island, was going out of business. I was looking around—they happened to have some old stones from broken jewelry that I could use in my work—when I overheard a couple discussing making a Christmas ornament by covering a period Chippendale brass backplate with glitter,” she says. “I thought, ‘that’s not a good idea,’ and bought out the store’s antique hardware to save it.”

Parcher subsequently haunted junk stores, flea markets, furniture stripping workshops, and architectural salvage emporiums in search of overlooked artifacts. Merchants came to know her wants and set things aside for her, from cans of handmade screws and nails to boxes of drawer pulls and the occasional clock finial. “A knob is missing. A handle is broken. In a million years you wouldn’t find exactly what you needed for a specific project, which is why dealers and conservators began contacting me,” she explains.

Parcher does not consider herself a scholar. She learns by looking and comparing, building on her training as a metalsmith by examining her finds for evidence of manufacturing and wear. She searches for the marks and abrasions left by tools, molds, stamps, and presses; delights in evidence of lacquer and gilding, sometimes fugitive after decades of exposure or harsh cleaning; and notes with interest the “dings” and “bangs” attesting to use over time. Her confidantes include Gary Sullivan, a Massachusetts dealer and fellow hardware enthusiast who has amassed a substantial collection of his own; and the Winterthur curator emeritus Donald L. Fennimore, a leading academic authority whose writings include a two-part article, “Brass hardware on American furniture” in this magazine in May and July 1991, and the book Metalwork in Early America: Copper and Its Alloys from the Winterthur Collection (1996), which includes a chapter on hardware used on American furniture.

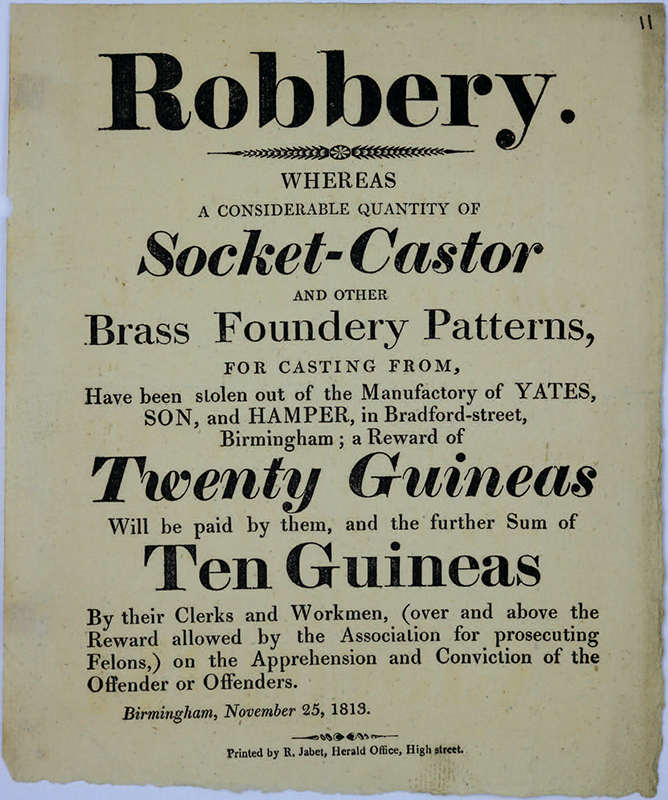

Parcher shares Fennimore’s keen interest in marked hardware, both English and American. Colleagues praise her ability to spot names, initials, and other insignia, along with her assiduous efforts to match these identifiers with period records. “Joan in her sleuthing has found marks that I did not uncover in my research,” Fennimore acknowledges, “so there is definitely more to be discovered in that realm.”

“I like to imagine Boston cabinetmaker Thomas Seymour choosing this pattern,” Parcher says, fingering a handle mounted on a pattern card. Each handle is stamped “HJ” on the back of its bail for Hands and Jenkins, the most prolific British maker of marked brass furniture hardware. According to Fennimore, William Jenkins was in business with Birmingham diesinker and engraver Thomas Hands as early as 1791 and is documented to have been working on his own from about 1805 to 1823, after which he was joined by his son.

On her workbench are two backplates marked “D K / 40s / PHILADa” on the reverse. Parcher, the first to detect the miniscule maker’s mark, explains: “There are two known brass founders in Philadelphia with ‘D K’ initials, Daniel King and Daniel King Jr. The style of these brasses coupled with a 1767 advertisement in the Pennsylvania Chronicle persuades me this is the work of the father. In all, I have six backplates and one escutcheon from this group; three have readable marks. Because the brasses were sand-cast, the delicate maker’s mark does not always cast clearly.”

Parcher owns catalogues and price lists for purveyors of reproduction brass hardware, among them Israel Sack, who early in the twentieth century offered imported “trimmings.” The dealer, who boasted in advertising that the dies used to make the replicas were exact copies of originals, supplied brasses “polished bright” or in “special old color.” Of the latter, Parcher says, “I don’t know what this patina looked like when it was fresh, but now it pretty much looks like brown shoe polish.”

Distinguishing between antique and vintage hardware can be challenging, even for experts. Fennimore advises, “You want to examine closely such things as surface, texture, weight, details of finish and outline, differences in the fronts and the backs of objects, evidence of age through stress cracking and that sort of thing—all features that are for the average person kind of boring and not really worth bothering over, but very important for the connoisseur.”

When the Yale University Art Gallery celebrated the opening of its new American Furniture Study Center in 2019, curator Patricia Kane invited Parcher to conduct a study session. Parcher took pieces from her own collection and borrowed others from Sullivan, who hopes one day to collaborate with the jeweler on an exhibition of antique hardware. “I’ve been working on a checklist for years. I like to accumulate the different styles. There are so many patterns and makers,” says Sullivan, who acquired most of Israel Sack, Inc.’s, inventory of period hardware from the estate of the dealer Wayne Pratt.

A beautiful set of brasses can transform a piece of furniture, even alter its price. But the jewel-like qualities of a backplate or knob are not, in the end, what most matters to Parcher. She says, “I’ve rescued collections that were a day away from going to the scrapyard. Making brasses was hard, dirty work. The workingclass people who made this stuff were wonderful craftsmen, yet few appreciate their art.”

The artist’s lifelong interest in recovering small things forgotten also finds expression in her latest line of jewelry, still in a conceptual phase but promising the variety she enjoys. As Parcher explains, “I’m working with recycled plastic. Turns out, with ninety-seven different colors it’s possible to produce nearly half a million different color combinations. I like learning about materials and making something from nothing.”