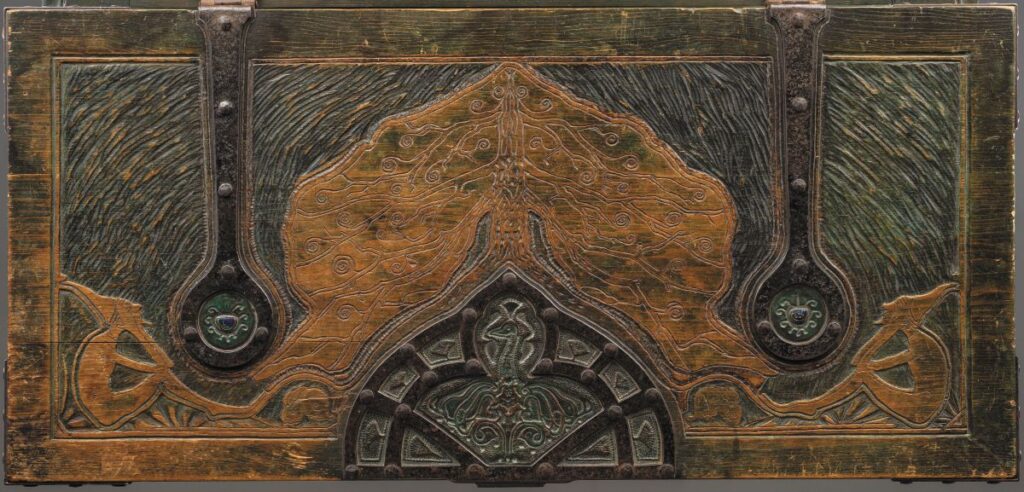

If Madeline Yale Wynne (Fig. 3), an artist and leading voice for the American arts and crafts movement, had not marked an oak chest she designed “MADE/ IN/ AMERICA/ 1903/ -MYW-,” it is doubtful we would be celebrating the discovery of that piece today (Fig. 1).1 The chest was unquestionably Wynne’s greatest artistic accomplishment, and she considered it “perhaps better than anything she had done.”2 Known as the Garden of Hearts chest for the decoration on its inner lid depicting a landscape of three inverted heart-shaped trees standing alongside a winding river, this chest is a tour-de-force of arts and crafts design (Fig. 2). Designed, built, and decorated when Wynne was fifty-eight, it stands not only as a reflection of her creativity and confidence as an artist, but also of her talents as a painter, metalsmith, and woodworker. Likely commissioned by an unknown patron for a bride moving to or living in England, the specific whereabouts of Wynne’s masterpiece was unknown for much of the twentieth century.3 The chest was in England until at least 1918 when its location was noted in a memorial volume for Wynne, who died the same year. At some later time, it traveled with a family to South America, where it stayed until it was given to the family’s nanny. The chest returned to England with her, and she later gave it to the son of the next family for whom she worked. It was he, near the end of his life, who in 2015 sent it to auction, where it was purchased by the London dealer from whom Historic Deerfield in Massachusetts acquired it.

Time had not dulled the luster of Wynne’s creation. The chest is now the centerpiece of the museum’s current exhibition Garden of Hearts: Madeline Yale Wynne and Deerfield’s Arts and Crafts Movement. The show features work by Wynne and other Deerfield artisans from the collections of Historic Deerfield and the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum and tells the story of Wynne’s remarkably diverse artistic talents and her innovative and progressive spirit.

Wynne was born on September 25, 1847, in Newport, New York, to Catherine Brooks and Linus Yale Jr.—inventor of the cylinder lock and co-founder of the Yale Lock Manufacturing Company. She and her family lived briefly in Philadelphia and Eagleswood, New Jersey, before moving to Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, in 1861. There, at age eighteen, Wynne married Henry Winn and had two children. The unhappy marriage dissolved in 1874, and in 1883 she changed the spelling of her last name from “Winn” to “Wynne.” With her mother’s help rearing her sons, Wynne was able to pursue her love of art.

Wynne’s earliest art training came in the small village of Deerfield—a place she would later call home. There, in 1872, she studied painting with Deerfield native George Fuller, who worked in the lyrical Barbizon style of landscape painting. Five years later, in 1877, Wynne entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and she continued her studies the following year at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. During her brief time there, Wynne seems to have excelled as a student—she would teach drawing classes at the school—before moving on to attend the Art Students League in New York in 1880.

There, she continued her study of painting under Walter Shirlaw, an artist of the Munich school, which emphasized dark tonal qualities. His influence can be seen in Wynne’s portrait of her friend’s daughter, Madelene Isadore Taylor (Fig. 7). Wynne followed her formal training with an extended trip to Europe where she met other women artists, including her future lifelong companion, Annie Cabot Putnam of Boston. Although capable in multiple mediums, including oils and watercolors, Wynne never considered herself a proficient painter. As she wrote to a friend: “I do paint, but it is mostly in my head and heart, for my unruly servant of a body refuses to obey many of my requests, and insists on playing lord and master.”4 After returning from Europe, Wynne and Putnam set up a studio in Boston for painting and metalwork.

Eager to return to rural western Massachusetts, Wynne purchased the 1770 Joseph Barnard house in Deerfield along with Putnam in 1885 as a summer home and renamed it the Manse (Fig. 4). They had a small forge built in a barn behind the house to pursue their metalwork. Their workspace was greatly augmented in 1890 when Putnam purchased the 1785 Hitchcock house (also known as the “Little Brown House”) in Deerfield, which she and Wynne used as a painting studio (Fig. 6). Their home and studio (later used as a reception space and venue for artisans’ lectures) eventually became important centers for the village’s burgeoning arts and crafts movement.

While Wynne considered Deerfield her home, she and Putnam typically resided there only during the summer months. Their participation in urban arts and crafts activities created significant networks for Deerfield. In Chicago, where Wynne resided with her brother, Julian Yale, during winters from 1890 to 1909, she not only served as a founding member of the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society in 1897, but also practiced and exhibited her metalwork and pursued writing, publishing her first book of fiction, The Little Room and Other Stories, in 1895. The following year, Wynne’s reputation was further established when the Chicago Daily Tribune likened her artistic and literary versatility to that of the great men of the Renaissance.5 Putnam spent her winters participating in the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston as a member and from 1908 to 1912 as a juror reviewing work for the society’s salesroom and exhibitions.

Beginning in 1899, annual summer exhibitions in Deerfield (Fig. 5) showcased linen-on-linen embroideries by the Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework (Fig. 9), an organization founded in 1896 by Margaret Whiting and Ellen Miller; as well as photography by Frances and Mary Allen and Emma Lewis Coleman; furniture; and metalwork by Wynne and Putnam (as seen on the mantelpiece and to the right of the fireplace in Fig. 5).

In 1901 Wynne took important steps to formalize these local craft initiatives by gathering a group of local residents at the Manse to create the Deerfield Society of Arts and Crafts, which incorporated the needlework group. Wynne was elected president—a position she held for life. The same year, Wynne invited a small number of women to her home to learn raffia basket weaving. The group became formally known as the Pocumtuck Basket Makers in 1902 (Fig. 11). Handicrafts produced under the aegis of the Deerfield Society of Arts and Crafts eventually expanded to include weaving by Luanna Thorn, Eleanor Arms, and others; wrought-iron work by Cornelius Kelley; basketry by the Deerfield Basket Makers alongside the Pocumtuck Basket Makers (Fig. 10); furniture by Madeline Wynne, Edwin Thorn, and Caleb Allen; pottery by Chauncey Thomas; and candlewicking (or tufted work) and netting by Emma Henry and others. The village was not only one of the earliest but a leading arts and crafts center in America, and through handicrafts Deerfield’s farsighted women effectively revitalized the economic life of the village and helped shape it into a cultural destination.

As an organization, the Deerfield Society of Arts and Crafts strove to maintain “a standard of excellence of design and integrity of workmanship” in its handicrafts.6 To ensure consistent quality, in 1903 Wynne, Putnam, and painter Augustus Vincent Tack were chosen as jurors to vet work produced by society members. In 1906 the Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework split from the Deerfield Society of Arts and Crafts, which then changed its name to Deerfield Industries. The village gained further prominence in 1908 when, as a vice-president (along with Arthur Wesley Dow) of the National League of Handicraft Societies, Wynne helped organize the group’s first annual convention there—an important showcase for local artisans and an opportunity to hear about advances in craftsmanship.

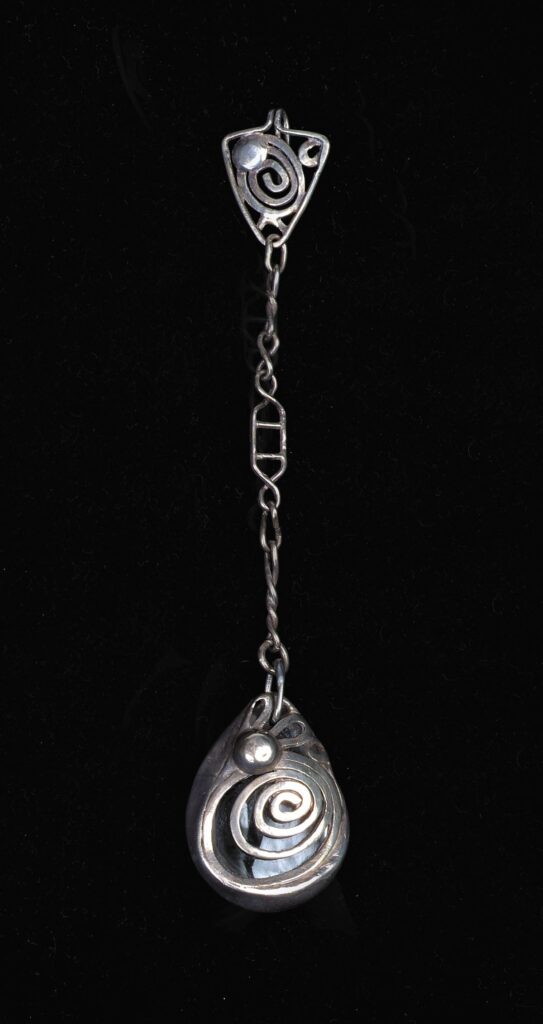

Wynne was not only a tireless promoter of arts and crafts ideology in Deerfield, she lived it through her artwork. Her most creative expressions came in metal, notably in the decoration of her Garden of Hearts chest. She credited her interest in the craft to her father’s workshop: “Being the daughter of Linus Yale Jr. the inventor of the Yale Lock I had a training in mechanics and access to shop and machinery, and thus naturally became interested in Arts & Crafts, developed my own line in metal work and enamels without instruction except as it had been gained by the foregoing experiences.”7 Wynne’s earliest piece of metalwork, a brass bowl of 1880 etched with chrysanthemums, shows her mastery of the material and refined sense of design (Fig. 8). Over time, she embraced looser, less representational designs. Wynne’s distinctive handwork, use of semiprecious gemstones, pebbles, and lesser metals such as copper and brass on her hand-hammered bowls, hairpins, jewelry, and belt buckles resonate with the ideals of the arts and crafts movement (Figs. 12, 13, 16). A November 23, 1902, Chicago Daily Tribune reviewer described her silver as having “the odd charm of looking quite primitive, while in perfection of form and finish they are equal to the best modern work.”

Wynne’s creativity and originality can also be seen in an undulating poppy-shaped copper bowl featuring punch-worked designs and a patinated red interior (Fig. 15). She exhibited her metalwork nationally to critical acclaim as well as in summer exhibitions in Deerfield from 1899 to 1914. Ahead of their time, Wynne’s modernist designs incorporating vigorous lines and animated surfaces paved the way for the next generation of metalworkers and artists.

Between 1899 and 1903 Wynne used “that inventive brain of hers, and those deft hands so skillful in many arts,” to design and build artistic furniture.8 A skilled woodworker, she created at least seven boxes (Fig. 18), and two full-sized “bridal chests,” as they were called in those days. The other besides the Garden of Hearts chest was made in 1899 for Bertha Bullock Folsom, daughter of the owner of a Chicago shoemaking firm, and is now in the collection of the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. Unlike other arts and crafts furniture, Wynne’s chests are imaginatively painted, carved, and ornamented with decorative metalwork.9 Well-versed in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century furniture-making traditions of the Connecticut River valley, Wynne wrote an article on the topic for the September 1899 issue of House Beautiful. The overall form of the Garden of Hearts chest takes its inspiration from examples such as the Abigail Allis, or “AA,” chest of about 1690 (Fig. 17). Similar to the Allis chest, the Garden of Hearts chest is built primarily using frame and panel construction. Wynne also re-created subtle period details, including the chamfered edges along the rails surrounding the front and side panels, and the molding along the corner posts and the drawer facade. However, in other areas, Wynne’s construction followed her own designs. For instance, unlike the Allis chest, she did not use wooden pins to join the rails to the posts. Additionally, instead of using a single large dovetail or nails to join the drawer sides to the drawer front—a technique commonly found on early chests—she used multiple small dovetails. Also departing from period examples, Wynne’s drawer is not side hung, but runs along the case bottom. Wynne’s use of a green stain and large strap hinges are also more characteristic of arts and crafts furniture than of period examples. Wynne was therefore not seeking to replicate the earlier examples, but to pay homage to their overall appearance, and to use their surfaces as a canvas of sorts for her own artistic creations.

Wynne’s decoration of the Garden of Hearts was also likely inspired by the inverted-heart motifs and elaborate vine and leaf carvings found on the Massachusetts pieces known as “Hadley chests” and boxes. The three front panels of a chest initialed “SH,” in the collection of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum, also bear an interesting resemblance to the three inverted heart-shaped trees in Wynne’s landscape. While the heart-shaped motif was a common one in early American decorative arts and was used to decorate a variety of items, from wrought-iron toasters to domestic textiles, Wynne did not confine herself to following historic precedent, but added her own joyful exuberance to the form she described as a bride’s chest.

The chest facade and sides feature stylized motifs in hammered-copper panels, and the lid exterior shows a majestic hammered-copper peacock outlined with wrought-iron strapping, and elves and rabbits nestled beneath a large oak tree, likely symbols that were meaningful to the bride for whom it was made (Fig. 20). The lid’s interior reveals Wynne’s brilliantly carved and painted landscape featuring orange trees with blossoms and fruit outlined in gold paint, and “the river of life [flowing] through the garden and the web of circumstances, some of earth, some heaven-born” (Fig. 2).10 To achieve some of this carving, Madeline employed pyrography—ornament created by burning wood with a hot metal tool. The landscape is framed in the upper corners by hammered- and pierced-copper butterfly wings set with cabochon stones (Fig. 19). Wynne likely commissioned a blacksmith to create wrought ironwork of her design for the chest. Known to have traveled by train between Deerfield and Chicago with projects in tow, Wynne likely worked on various components of this chest in both locations.

In 1911 Wynne and Putnam started wintering in the artistic community of Tryon, North Carolina. There, Wynne continued writing. She published the short story collection Si Briggs Talks in 1917, and died the following year in Asheville, North Carolina, on January 4. Although Deerfield’s handicraft production was paused by World War I and a change of leadership at Deerfield Industries after Wynne’s death, crafts continued to be produced under the organization’s auspices until 1941.

Employing all of her talents as a woodworker, metalworker, and painter, the Garden of Hearts chest truly stands as Wynne’s magnum opus and as a celebration of hand craftsmanship. As a missionary of arts and crafts philosophy, Wynne left a legacy not only through her artwork but also through craft organizations that inspired the work of many artists. One friend aptly captured Wynne’s spirit, writing in 1918:

She gave freely of herself to all with whom she came in contact, and no one met her, even casually, who did not retain a vivid impression of her gracious, “generous-seeking” personality. She was so much more than the sum of all her varied gifts—a beautiful woman, with singular, exceptional charm of voice, manner, gesture; artist, craftsman, unique story-teller, writer of prose and poetry (too little known); loving daughter, sister, mother, and most satisfying friend.11

It was precisely Wynne’s versatility and her ability to find the genius in everyone that allowed her to become a critical leader not only in the development of the arts and crafts movement in Deerfield, but in communities throughout the country. In the creation of the Garden of Hearts chest, Wynne gave it her heart and soul, resulting in what is perhaps one of the most significant pieces of American arts and crafts furniture made by a woman.

Garden of Hearts: Madeline Yale Wynne and Deerfield’s Arts and Crafts Movement is on view at Historic Deerfield’s Flynt Center of Early New England Life in Deerfield, Massachusetts, to March 3, 2024. A related exhibition on the arts and crafts movement in Deerfield, Skilled Hands and High Ideals, is on permanent view at the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum. Visit artscrafts-deerfield.org

1 Much of the information presented in this article on Wynne’s life and the arts and crafts movement in Deerfield is drawn from and discussed more extensively in Suzanne L. Flynt, Poetry to the Earth: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Deerfield (Stockbridge, MA: Hard Press Editions, in association with Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, MA, and Hudson Hills Press, Easthampton, MA, 2012). 2 Annie Cabot Putnam to Isadore Pratt Taylor, December 1, [1918], Taylor Papers, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library, Deerfield, Massachusetts. 3 The chest was well known at the time it was made after being reproduced in Madeline Yale Wynne, “The Influence of Arts and Crafts,” Good Housekeeping, vol. 37, no. 1 (October 1903), p. 329. 4 Madeline Yale Wynne to Isadore Pratt Taylor, October 7, 1891, Taylor Family Papers, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library. 5 “A Gifted Chicago Woman: Versatile Madeline Yale Wynne,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 26, 1896. 6 Constitution of Arts and Crafts Society, Deerfield Industries Minutes Book I, 1901. Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library. 7 Society of Arts and Crafts Boston questionnaire, 1906. Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library. 8 Harriet Monroe, “An Easter Bride’s Chest,” House Beautiful, vol. 11, no. 6 (May 1902), pp. 365–366. 9 See “Chicago Women’s Wedding Chests,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 4, 1903. 10 Wynne, “The Influence of Arts and Crafts,” p. 329. 11 Elizabeth Head Gates, in In Memory of Madeline Yale Wynne (n.p., [1918]), pp. 22–23.

SUZANNE L. FLYNT was curator of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum for thirty-five years, and is the author of Poetry to the Earth: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Deerfield (2012). She is now a trustee at Historic Deerfield.

DANIEL S. SOUSA is assistant curator at Historic Deerfield with primary responsibility for the furniture collection. With Suzanne L. Flynt, he co-curated the exhibition Garden of Hearts: Madeline Yale Wynne and Deerfield’s Arts and Crafts Movement.