The newly opened Cooper Hewitt points the way for the immersive, participatory, digitally enhanced museum of the twenty-first century

If there’s one thing that is emblematic of the revolution that has just occurred in the old Andrew Carnegie mansion on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, it’s the heavily patinated, exquisitely restored, oak-paneled wall in the Great Hall that swings open to reveal an industrial-scale freight elevator. The Carnegie mansion is still home to what was once known as the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, an outpost of the Smithsonian that has now banished its hyphen, flung open its doors, and reinvented itself as a twenty-first-century digitally enhanced experience. Like that pivoting wall, this new Cooper Hewitt-which opened in December after a three-year period of reinvention and reconstruction-displays an unexpected utility while revealing activities that normally transpire behind the scenes.

Another thing about Cooper Hewitt: Like that wall, it’s not intended to stand still. “Everything at Cooper Hewitt right now is an experiment,” says Caroline Baumann, the museum’s director since June 2013, as workers were preparing the place for its first regular visitors since she took the job. “Design is all about experimentation. It’s about improving our world.” It isn’t a thing, in other words; it’s an act, and needs to be presented as such. “The last thing we want to do is focus on pretty objects. We want to focus on design’s power to change.”

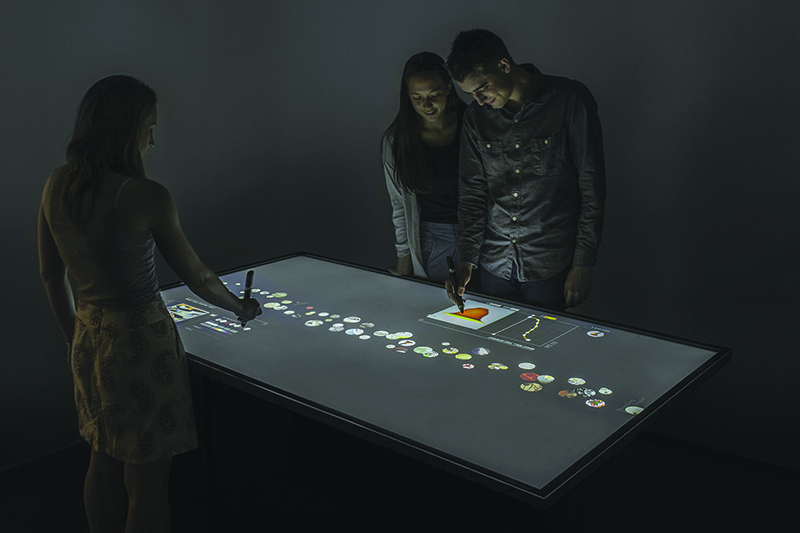

This becomes apparent when you walk through the Great Hall, a seventy-foot-long expanse of Scotch oak and teak, and through a small antechamber to the museum’s new Process Lab. There, in an oak-paneled corner room that once served as Carnegie’s private library, stands a pair of stark gray slabs that have approximately the same relationship to their surroundings as the mysterious monoliths in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. These are interactive tables, equipped with eighty-four-inch, ultra-high-definition touch screens that are designed to work with an electronic “pen” that’s intended to be central to the museum’s visitor experience. Long, rather thick, and cylindrical, the pen creates a record of your visit, storing information about any object you want, while at the same time serving as a tool for learning the history of design and even for designing things yourself.

Draw a shape on one of the interactive tables, for instance, and the table will automatically display an object in the collection that matches that shape-or a whole sequence of objects, providing a history of that shape through the ages. Alternatively, you can use the pen to create your own design, which with a bit of digital enhancement can be tidied up, replicated, and transformed into a pattern that can be printed on a length of fabric, or maybe a tote bag. “It’s a whole new philosophy-getting away from observation and jumping into participation,” Baumann says. “We’re saying, ‘Take the Pen. Write on the table. Have a ball. Learn about design.’ It’s the opposite of the usual museum policy.”

This is a philosophy that’s increasingly appealing-particularly to the generation born between about 1980 and 2000. In recent years experiences that involve participation and immersion have proven hugely popular-so much so that the JWT advertising agency recently named “immersive experiences” number one among its top ten trends. This has led to such unlikely developments as a revival of performance and installation art, with people standing in line for hours outside the Museum of Modern Art to sit opposite Marina Abramović, silent and motionless, or outside a Chelsea gallery to spend forty-five seconds in a mirrored room that was designed by the eighty-five-year-old Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama to provide a suggestion of infinity.

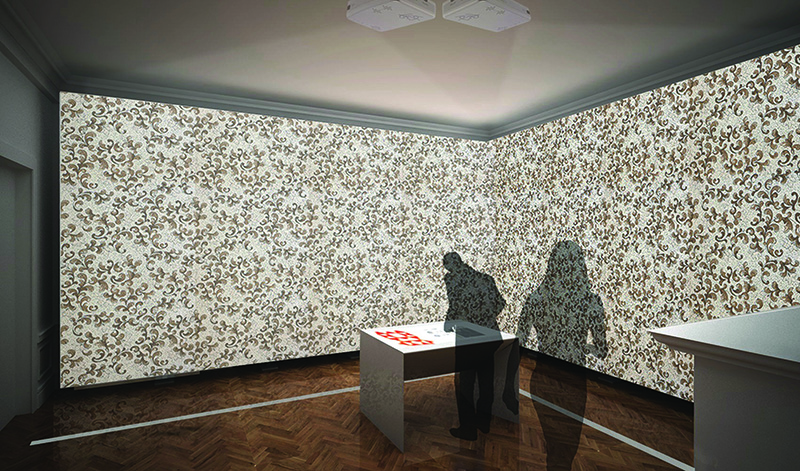

Such enthusiasms help explain Cooper Hewitt’s Immersion Room, an upstairs chamber that’s been given over to the museum’s extensive collection of wallpapers. Viewers won’t see any actual wallpaper; it would be impossible to show more than a handful of swatches at a time, and a display like that would hardly be immersive. Instead, they’ll be able to electronically project some three hundred of the museum’s more than ten thousand wallpapers onto the four walls of the room that was previously the director’s office. “I love the metaphor,” said Baumann. “What used to be a private space will probably become one of the most popular spaces in the museum.”

All this puts Cooper Hewitt at the forefront of current museum thinking. Sir Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate, recently described the ideal museum as “a forum as much as a treasure box.” That is quite a contrast with the attitude of a century ago, when Benjamin Ives Gilman, secretary of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, decreed that a work of art should be considered “a pure object of contemplation” that exists to “be seen in its perfection”-and that the function of a museum was to present it as such. Thus we have the Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrating its reconstruction of a fifteenth-century Adam-a six-foot marble reduced to bits when it tumbled from its pedestal twelve years ago-by posting a video online that details its reconstruction. “We live in a time when the public wants to look behind the scenes,” the New York Times was told by Emilie Gordenker, director of The Hague’s Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis-which will soon stage a major exhibition on a high-tech forensic investigation of a painting once thought to be a Rembrandt masterpiece.

What’s most intriguing about the reimagining of Cooper Hewitt, however, is not that it is in line with current trends but that it actually fits in with a long tradition of people seeking something more than connoisseurship for its own sake. Even Gilman made a distinction between a fine-art museum, which he described as “in essence a temple,” and a museum of science, “in essence a school.”

Design rests somewhat uneasily between art and science, but Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt, the sisters who founded Cooper Hewitt in 1897, left no doubt where they stood on the issue. Granddaughters of the inventor and industrialist Peter Cooper, who had established New York’s Cooper Union forty-four years earlier as a free school for the practical education of men and women alike, they regarded their museum as a place to learn. “Restrictions are eliminated, except the few necessary to protect the objects,” Eleanor wrote in a 1919 pamphlet entitled The Making of a Modern Museum. The sisters had begun collecting rare textiles before they were sixteen; with the help of wealthy benefactors like J.P. Morgan, they amassed a stunning collection of prints, carpets, jewelry, and the like. But protecting the objects was not their paramount concern. “Naturally constant use will have a tendency to damage, even destroy certain objects,” Eleanor continued, “but irreparable damage could not be accomplished under a hundred years, and if in that time an artistic tradition passed on from father to son…has been created, the existence or non-existence of these objects will not seriously matter, and during all that time the Museum will have been fulfilling its destiny.”

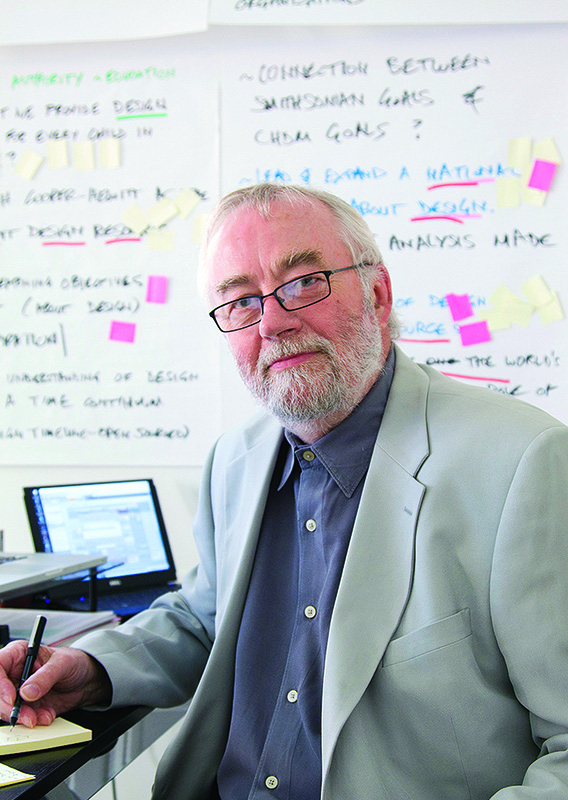

“That’s kind of awesome, right?” asks Sebastian Chan, the museum’s digital and emerging media director, who came to Cooper Hewitt three years ago from the Powerhouse Museum, a science and technology institution in Sydney, Australia. “Art museums can talk about the finished piece,” he continues. “But we’re interested in how it got to be a finished piece and what choices were made-political, economic, not always aesthetic. I like to think that if the Hewitt sisters were alive now, they would kind of enjoy this.”

Learning has changed since their day, however. The challenge Chan presented to Diller Scofidio and Renfro, the architecture firm that designed Cooper Hewitt’s new display systems, and Local Projects, the media design firm that developed the concept for the pen, was one the Hewitt sisters might have found liberating: Give visitors permission to play. Audio guides and museum apps offer information galore, but nowadays you can get information online; what you can’t get is hands-on experience with design itself. “We had a whole series of crazy ideas,” says Jake Barton, Local Projects’ founder. “They picked probably the craziest one-to invite visitors to be designers by drawing on the wall.”

Switching its focus from object to experience was only one part of the trial Cooper Hewitt faced in reinventing itself. The other part had to do with design itself. In 1963, when the museum was evicted from its original home-the top floor of the Cooper Union building in lower Manhattan-it looked as if it would have to shut down forever. Instead, after much hue and cry, it was acquired by the Smithsonian and installed in the Carnegie mansion, which had been leased since 1949 to the Columbia University School of Social Work. The rescue worked, but the museum has faced a formidable design challenge ever since: How to accommodate itself to a building that is more an historical example of design than a natural setting for it.

The Carnegie mansion-completed in 1902, shortly after Andrew Carnegie sold his steel empire to J.P. Morgan and began a new life as a New York philanthropist-is hardly a neutral backdrop. Looming within its imposing Georgian revival exterior is an idiosyncratic collection of rooms more suited to a Gilded Age industrialist than to a contemporary museum, festooned as they are with carved wood, decorative plasterwork, even actual gilding. Into this grand, faux-baronial setting the young architectural firm of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates-later renowned for sensitive renovations of such New York landmarks as Radio City Music Hall and the New Amsterdam Theater on Forty-second Street-dropped a clumsy assemblage of bland display cabinets illuminated by 1970s track lighting. Not only were the contemporary elements clichéd; they fought actively with their surroundings. “It wasn’t taking best advantage of the spaces,” says Richard Southwick of Beyer Blinder Belle, the firm that handled the just-completed interior renovations, choosing his words carefully. “And the spaces themselves were not very conducive to showing modern design.”

With Gluckman Mayner Architects as the lead firm for the renovation, Beyer Blinder Belle undertook a detailed inventory of the mansion and a neighboring pair of 1902 town houses that complete the museum complex. By this time the bulk of the museum’s holdings had been relocated from the town houses to a storage facility in New Jersey, and its administrative offices and extensive National Design Library had been moved from the third floor to the town houses. This meant the architects were able to open up almost all of the mansion for exhibits. The main rooms on the first and second floors-about twenty of them-were restored to their original condition, give or take the occasional pivoting wall. Most of the third floor, where library stacks had been installed in what had originally been a series of guest rooms, has been opened up and converted into a white-box gallery-at six thousand square feet, the museum’s first.

That space is currently given over to an exhibition on tools, one that focuses on their role as extensions of the human body. But it’s a couple of smaller exhibits downstairs that speak more directly to the past and future of Cooper Hewitt. In the second-floor Teak Room-so-called because it was paneled in Indian teak by Lockwood de Forest, a protégé of Frederic Church and guiding light of the nineteenth-century aesthetic movement-is an exhibit on de Forest himself. Down the hall, in the Carnegies’ bedroom wing, is the first show ever devoted to the Hewitt sisters and their collection. And on the first floor, in a suite of period rooms expertly redefined as exhibition space by Diller Scofidio and Renfro, is an exhibition called Beautiful Users-a show that more than any other defines the museum’s new attitude.

Organized by Ellen Lupton, a longtime Cooper Hewitt curator whose credits include a show about skin, Beautiful Users is dedicated to the memory of Bill Moggridge, the man most responsible for setting the museum on its current course. Moggridge was a cofounder of the pioneering design firm IDEO and the inventor of the 1982 GRiD Compass, the first portable computer to resemble the laptops we use today. In 2010 he was named director of the museum; two years later, at the age of sixty-nine, he died of cancer.

Beautiful Users is about the ever-evolving relationship between humans and the things they design for one another. Among other things it features a succession of telephones by the eminent twentieth-century designer Henry Dreyfuss, who in contrast to contemporaries like Norman Bel Geddes and Raymond Loewy believed in the primacy of function over style. Dreyfuss’s 1937 Western Electric Model 302 is a classic high-shouldered rotary-dial phone; unfortunately, its handle has a ridge because no one imagined at the time that people would want to cradle the receiver between their shoulder and their ear. Twelve years later, after extensive testing, he introduced the more ergonomic Model 500, which became the standard desk phone of the 1950s. Then, after realizing that women in particular liked to lie in bed and talk while resting the phone on their chest, he developed the Princess, a lightweight model that was intimate and fun and kind of sexy.

The point of this show is that, thanks to people like Dreyfuss and Moggridge, design has progressed from an industry that thinks of people as consumers to one that sees them as users-as active and unique rather than passive and fungible. This kind of advance is what the new Cooper Hewitt aims to celebrate and encourage. But there’s nothing new about that aim: In her 1919 pamphlet, Eleanor Hewitt wrote that she and her sister “were trying to create a practical working laboratory” in their grandfather’s memory. Nearly a hundred years later, their successors are working to complete it.