Fig. 1. The Maloof Historic Home and Workshop stand on nearly six acres in Alta Loma, California, moved from the original site in the path of an interstate highway. Except as noted, photographs are courtesy of the Maloof Foundation.

Fig. 2. They are surrounded by a drought-tolerant garden in the foothills of Southern California’s San Gabriel Mountains.

The Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts is not where it should be. The six-acre compound in Alta Loma, just east of Los Angeles, showcases the remarkable art and life of one of the premier woodworkers of the twentieth century and occupies a remote site that enjoys a panoramic view of the San Gabriel Valley. Between 1953 and 2001, however, the house and workshop sat on a different site, in a lemon grove some three miles away. That location was in the path of the proposed 210 freeway, and the buildings would have been condemned to destruction or removal at the owner’s expense had they not been identified as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. In a monumental venture in historic preservation, the main house, several outbuildings, and some twenty large trees were moved to the present location. (The compound was formally listed on the National Register in 2010.) The Maloof Foundation, chartered in 1994 to oversee Sam’s legacy, mark its twenty-fifth anniversary this year.

Maloof belongs to the generation of American artists who returned from World War II and attended art school on the GI bill. By the end of the 1970s, he and other artists of his generation—including ceramists Peter Voulkos and Rudy Autio as well as the younger metalsmith Albert Paley and glassblower Dale Chihuly—had transformed the materials of craft into the stuff of sculpture. Even audiences uncomfortable with the abstract painting at the center of postwar art were drawn by the familiar materials and riffs on functional forms in their work. By the end of his life in 2009, Maloof’s renown was matched by that of a roster of clients that included Presidents Reagan and Carter (himself a woodworker.)

Like so many American success stories, Maloof’s was an unlikely one. The son of Lebanese immigrants, he was born in 1916 in Chino, a small town in the area of Southern California known as the Inland Empire. At that time, the IE resembled an orange-crate painting of sunny orchards and snow-covered peaks; it would remain Maloof’s home throughout his life. The area’s intellectual and artistic hub was the Claremont colleges, where his adult life unfolded. Maloof began his artistic career working as a studio assistant to Millard Sheets, the head of the art department of Scripps College and a multitalented artist and architect who seemed to know everyone in Southern California’s burgeoning postwar art scene. At Claremont, Maloof also met Alfreda Ward, a fellow ex-GI and an art student, who became his wife.

Prior to their marriage in 1948, Alfreda had worked at the Indian School in Santa Fe and brought a love of Native American art and artists into their life together. Examples of her paintings of Native subjects are displayed in the Maloof house, as is the extensive collection of Indian ceramics the couple collected. She gave up art making to run a household that would include a son and adopted daughter, and she played a central role in the founding and operation of Sam’s workshop.

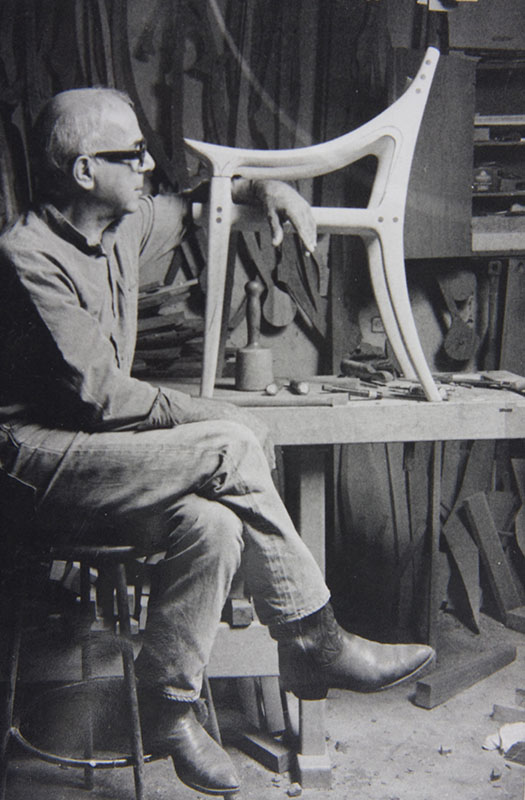

Self-taught, Maloof quickly displayed increasing skill in woodworking. With its architectural articulation and deceptive impression of simplicity, his curvilinear furniture of eastern black walnut couples the Japanese-inflected architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright with stripped-down mid-century Scandinavian furniture design. Its elegance reinforces the wisdom of his decision to eschew industrial fabrication in favor of the single, unique, artistic creation: it reminds us that the difference between art and mass-produced craft or design is the inherent characteristic of art as a vehicle for ongoing experimentation and refinement.

Maloof’s work reached a national audience when House Beautiful published it in 1954. The coverage brought him to the attention of the eminent industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, whose designs ranged from the Princess telephone to John Deere tractors. As James Rawitsch, executive director of the Maloof Foundation points out, “Sam’s connections with Millard Sheets is well known. But there is also a fascinating, untold story in his relationship with Henry Dreyfuss.” Newly arrived on the West Coast, Dreyfuss would commission furniture from Maloof for his South Pasadena home and introduce him to well-placed clients.

Maloof began building his house in 1953 and tinkered with it until his death in 2009. By then, what began as a small cottage had morphed into a two-story, ten-thousand-square-foot house with a dozen or so rooms—depending, that is, on how you define room. Additional spaces were added—often shotgun style, without hallways—as Maloof’s finances improved. With further additional income, he literally raised the roof of nearly every one of the initially flat-roofed additions he had made to the original house. The result is a colorful, snaggletooth roofline calling to mind the tents of a medieval “faire.” Among the handsomest rooms is the airy bedroom housing dozens of Indian pots and a set of pint-sized furniture for children. It also showcases Maloof’s first and last chairs—the former an angular, Bauhaus-inspired work with a seat and back fashioned from clothesline; the latter a gorgeously curvy rocker, his signature form, produced in the final months of his life.

Alfreda died in 1998, three years before the move to Alta Loma. Friends feared that her death and the demands of the move might prove fatal to Sam. Instead it seemed to energize him. He was instrumental in planning the relocation of the house and workshop—still functioning today under master woodworker Mike Johnson—as well as in designing a new residence and a handsome gallery for Maloof-related exhibitions and events related to the foundation’s increasing attention to environmental concerns. This last interest—which has resulted in such additions as the foundation’s drought-tolerant demonstration garden and wildlife habitat—derives from the influence of Beverly Wingate, whom Maloof married in 2001 and who was the principal landscape designer for the new site. An active member of the board, Wingate continues to live in the residence Maloof designed for the site.

In 2011 the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino mounted an exhibition of Maloof’s work affectionately titled The House that Sam Built. The show was suffused with the warm and embracing spirit that Maloof nurtured, and that gentle character of place is immediately felt when visiting the foundation.

Fig. 10. This 2011 rocker, made of zircote (height 45 1/2, width 23 1/2, depth 46 1/2 inches) is one of many produced after Maloof’s death by Sam Maloof Woodworker, Inc. which holds an exclusive manufacturing license. Photograph by Schenk and Schenk Photography.

Fig. 12. Maloof was still working in his nineties, designing the Curved Back chair in 2009. It is made of walnut with fabric by Jack Lenor Larsen; height 40, width 29, depth 35 inches. Schenk and Schenk photograph.

The Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts is located at 5131 Carnelian Street in Alta Loma, California, and is open to the public on Thursday and Saturday. Tour reservations advised. malooffoundation.org