We’ve been here before . . . sort of. A century ago, from 1918 to 1919, an influenza pandemic swept across the globe. Doctors still had much to learn about infectious diseases, and the ongoing chaos of the Great War disrupted the epidemiological control measures that were put in place. All but unconstrained, the flu killed at least 50 million worldwide—675,000 in America alone.

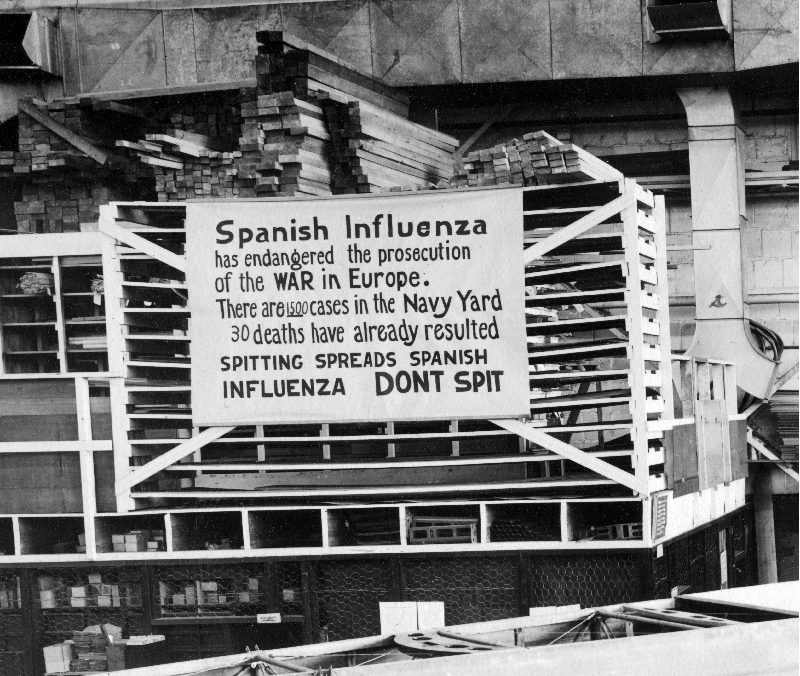

This cataclysm has been much on people’s minds recently, for obvious reasons; but in this case, historians were ahead of the curve. The centennial of the influenza pandemic was met by a flurry of new scholarly studies, as well as items in the popular press, and at least one exhibition: the forthrightly titled Spit Spreads Death, at the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. It opened in October 2019 and is still on view now—though like almost every other museum in America, the Mütter has had to close due to the coronavirus. Yet, if ever an exhibition acquired sudden relevance, this is it, so I decided to pay it a vicarious visit by making contact with Jane E. Boyd, who served as the project’s historical curator.

Spit Spreads Death focuses on what happened in Philadelphia in the autumn of 1918, in the wake of an infamous triggering event, the Liberty Loan Parade held on September 28 to raise funds for the ongoing war effort. The day itself seemed like a great success. Two hundred thousand people attended; John Philip Sousa and his band played. But only two days later, the city’s population began to fall ill. Schools and other institutions were swiftly closed down to halt the spread of the disease, but it was too late. In the first six weeks, almost fourteen thousand had died—one every five minutes. By six months after the parade, the city’s pandemic death toll had topped 17,500.

My first question to Boyd, as you might imagine, was what these long-ago experiences have to tell us about how to cope with the coronavirus. For her, it came down to one word: transparency. Partly due to wartime censor-ship, partly through a misplaced desire not to spread panic (or erode its own credibility), the government was loath to inform the population just how bad the problem was. Doctors’ early warnings were suppressed. Unsubstantiated rumors flew: the Germans had started it on purpose; you could self-medicate with whiskey. What we have now learned to call “social distancing” regulations, though they were implemented, met with only erratic compliance.

Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it, as the adage goes, and already we know that some of the mistakes made back then have happened again, first in China, and then elsewhere in the world. This being The Magazine ANTIQUES rather than the New Yorker, though, I wanted to ask Boyd about something else: how on earth do you make an exhibition about a pandemic? She told me—no surprise here—it was difficult. As part of its research, the team undertook an ambitious project to transcribe all the death certificates registered in Philadelphia during the period of the outbreak (an enormous archival effort, led by historical epidemiologist Nicholas E. Bonneau). This study yielded “a granular picture of the spread of the disease,” as Boyd puts it, which could be specified not only in relation to location, but also demographic information like race, immigration status, and occupation. Visitors and medical researchers alike have been fascinated by this statistical portrait of the calamity.

You don’t make a show out of numbers alone, though. The curators faced a unique challenge: as dramatic as the pandemic was for those who lived through it, it actually left very few identifiable artifacts in its wake. The initial onset was so sudden, so all-consuming, that the usual rites of legacy were disrupted. Cemeteries and casket makers were just as overwhelmed as hospitals; many victims were buried in temporary mass graves. Countless pieces of furniture, ceramics, silver, jewelry, and other items now floating around on eBay were owned by those unfortunate people, but the event left no mark on these objects, leaving them only silent witnesses.

It’s a sobering thought: the abyss that claimed so many lives also registers as an absence in the artifactual record. Historians have described the 1918 flu outbreak as a “forgotten epidemic.” People simply didn’t have the time, resources, or perhaps the emotional wherewithal to form an immediate response. Boyd notes that mourning tended to be “quiet and private, with no public memorials,” and that “many of those who lived through the disaster simply didn’t want to talk about it.” She and her colleagues have, however, been able to collect family stories from descendants and have also found just a few accidental object survivals, which help bring home the reality of what happened.

Boyd singled out for attention the story of Naomi Whitehead Ellis Ford, a resident of southern New Jersey. She was expecting a child that fateful autumn, and went into Philadelphia to do her Christmas shopping early—even writing out tags for the gifts to her family members. Then she died. The presents, never delivered, somehow made their way into an attic, and eventually to the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection at Drexel University. Today, these otherwise unremarkable objects—an embroidered handbag, a corset bag, celluloid hair combs—seem to perfectly embody what was lost in 1918. They don’t inform us in the way that statistics do, but they remind us of something just as important: what it was not to know what was about to happen.

In these difficult times we might pause to reflect on Naomi Ford, and the many others who shared her fate. (Boyd and her colleagues had the same instinct, working with the artists’ group Blast Theory to stage a public procession in honor of those killed in the influenza pandemic—drawing to a close the story that began, inadvertently, with a parade.) We should even be grateful to them; for had they not died so suddenly and so tragically, we would doubtless be in a far less prepared position today. As horrific as the coronavirus is, it is certain to be far less deadly than the flu was then; if we are wiser now, it’s only because we’ve learned from the past. Only time will tell how much.