I was raised in a UU church. That’s one U for Unitarian, signifying belief in one God and a denial of the Trinity, and another U for Universalism, the conviction that all souls will ultimately be saved. By the time I came along, though, these theological points had faded into obscurity. The two Us had gotten together in 1961, two liberal pathways merging into a single Unitarian Universalist church, without doctrine or dogma. UU services retain the trappings of Protestantism—pews, hymns, and sermons— but the only real creed on offer is tolerance.

Given this generally open-minded stance, our Sunday School was a varied affair. Over the course of a year we might have a visit from a Jewish rabbi, a Catholic priest, a Protestant minister, and a Native American elder, each of whom explained their own belief system. It was meant to be enlightening, and it was. But it also had the effect, at least for me, of inoculating me against religion in general. To this day it is something I view, respectfully, from the outside.

I offer this personal history as a preface to a set of remarks on spirituality and material culture, a topic that is necessarily approached from the vantage of one’s own beliefs—or lack thereof. UUs are very few in number, especially outside New England. (It used to be said of Unitarians that they believed in “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Boston.”) We are, however, representative of a general trend. It’s often said that we live in an increasingly secular society, and in the United States at least, the statistics bear this out. Church attendance has steadily declined for decades. An increasing number of Americans profess no religious affiliation at all. To be sure, there are plenty of devout people in this country, but more and more of us are not. When we experience religious artifacts, it’s likely to be in a museum.

What happens when we do have that encounter? When a non-believer like myself is actually moved by a religious artwork, getting past questions of style or iconography, truly connecting with it as a profession of faith? Art historian James Elkins explores this question in the 2004 edition of his book Pictures and Tears, an idiosyncratic history of people who cry in front of paintings. Noting that this was once a common experience— often had in church—he wonders what we have lost by seeing art in intellectual and aesthetic terms, rather than as something sacred. Elkins comes to feel that the contemporary art viewer’s experience “is suffused with a lingering nostalgia for a time when religion could be named, and tears could be believed.” Though, he adds, “I can’t prove it, because the subject—even in this age of apparent freedom of speech—is proscribed.”

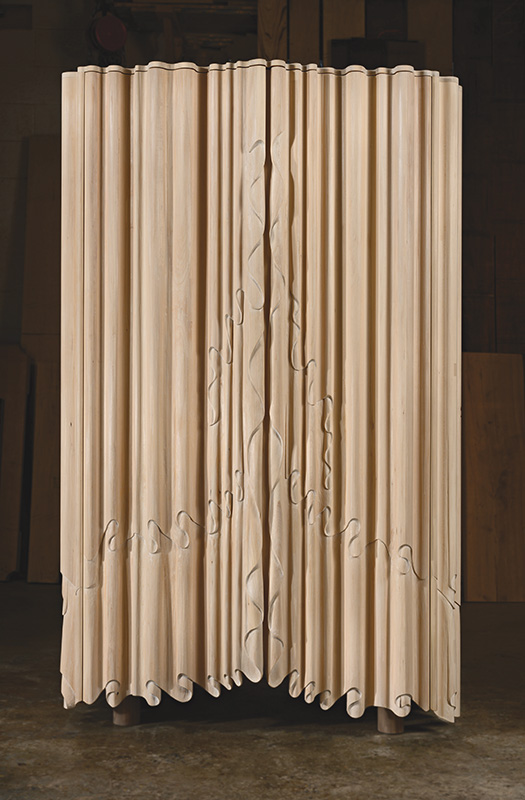

A designer of my acquaintance, Christopher Kurtz, has been thinking along similar lines. Like so many other creative spirits, he has been spending a lot of time alone in the studio over the past year, pouring himself into his work. His latest creation is an imposing 76-inch tall armoire carved in linden wood. It is replete with interesting features—the interior is sheathed in gold-hued milk paint, and the top, typically unseen of course, is veneered in walnut burl. The main event, though, is the object’s gorgeous, undulating facade.

The design is inspired by “linenfold” carving, the type that graced late medieval architectural paneling and furnishings. This idiom evolved through the inherent logic of chisel-work—long flutes capped by tightly orchestrated gouge cuts. It also clearly alludes to classical drapery, and has something of the abstraction that emerges unbidden in the whirling garments of antique sculpture, or the passages of drapery seen in contemporaneous paintings—motifs yearning to breathe free of the burden of representation.

Kurtz was interested to learn, while developing the idea for his armoire, that linenfold, and the Gothic, or “perpendicular” style more generally, reached their height in the wake of the Black Death of the fourteenth century. The relative austerity of the style reflected a shortage of available labor—so many craftspeople had died—but also, as Kurtz puts it, expressed a need for “pure expression of form, confronting the gravity of mortality and loss.” Seen from this perspective, the insistent verticality of linenfold is a diagram of apotheosis: a sheaf of vectors, all pointing up to heaven.

As Kurtz also notes—using a line attributed to Mark Twain— “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” At a time of plague, making the armoire has given him focus. “I’ve wrestled with the issue of how and why to make art,” he says, “when so much of the world population is sick, dying, or has lost their livelihoods and homes.” The magnificence of his carving, however implicitly, provides his response. And to my way of thinking, it’s deeply meaningful.

As I said, everyone speaks from their own point of view on these matters, and I am no doubt influenced by my UU upbringing. I may not “believe,” in the sense that a religiously observant person does, but I have utmost reverence for, well, unity and universalism—all that humans fired by faith have achieved, wherever their personal devotion has led them. So in my eyes, Kurtz’s transposition of Gothic ornament into an entirely secular context keeps its true significance intact. His carved folds, just like those of the fourteenth century, manifest the human impulse to render matter transcendent.

Kurtz made his armoire for Objects: USA 2020, an exhibition I’ve co-curated for the gallery R and Company in New York City. Our title refers to an important project of fifty years ago, which surveyed current craft activity across the nation. Back then, the studio craft movement was at its height, as was the counterculture; the handmade was “way in.” Today that vitality is back in force, partly as a reaction against digital technology, which has given us so much, but at a steep price, claiming our attention in return, and increasingly, displacing humans from their vocations. Artificial intelligence is often discussed in the hushed and awe-struck tones we reserve for the gods. But, actually, it is the ultimate secularism. Computers are gradually learning to outsmart us, but they’ll never learn what it is to feel wonder, or reverence.

The pandemic has been a grim reminder of how fragile we humans are. It also has shown our resilience and creativity. Right now, people all over America are in their garages, sewing rooms, and home workshops. Their private acts of making, devotional in spirit or not, are filling the days. At the same time, the detachment from spirituality that Elkins describes—the feeling of separation— has become all too literal. We can’t go to church even if we want to, for fear of contracting or spreading disease. Many art institutions are closed, for the same reason. When we are able to return, will we feel differently? Will we all, collectively, step into the nearest museum, and break down crying?