Americans are growing more fascinated with Aboriginal art, which John and Barbara Wilkerson have been collecting since 1994.

The passion for collecting settles on folks in myriad ways. A certain form catches the eye, or a special object from an eventful time in one’s life emerges to become a kind of talisman, and if one of such a thing brings a singular joy, how much pleasure will multiples generate? Over time collectors may shift their focus, selling off their art deco material, perhaps, and moving on to mid-century modern. And while it’s possible to surround oneself with, say, Charles Dana Gibson images and the photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe, the variety within most collections expresses a kinship. The fanciful simplicity of the vernacular, the highly personal need for expression manifested by the marginalized, and an articulation of origins and existence beyond the immediate grasp of Western viewers are the unifying aspects of the diverse collection assembled by New Yorkers John and Barbara Wilkerson.

When the Wilkersons were young and newly wed, they needed things to set up housekeeping in the old farmhouse they called home in Ithaca, New York. “John’s an excellent woodworker, and Ithaca was a gold mine for collecting derelict furniture,” Barbara says, so the couple had no trouble assembling the requisite tables and chairs. But Barbara had an eye for something more: American folk art. “Our first purchase was a weathervane, and it took off from there,” she shares.

The couple went on to amass a substantial collection of nineteenth-century weathervanes made by one of the country’s earliest manufacturers—J. Howard and Company of West Bridgewater, Massachusetts—as well as painted chests, shop signs, barber poles, and more. In time, the Wilkersons became great champions of the American Folk Art Museum, where John served as board president from 1999 to 2004. In 1995 the Wilkersons ventured into self-taught/ outsider art, acquiring work by Bill Traylor (c. 1853–1949), a formerly enslaved artist, whose first pencil drawings date to 1939, and Martín Ramírez (1895–1963), who spent the last fifteen years of his life confined to the DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, California, where he created hundreds of intricate illustrations.

But the arc of their collecting took a major defining swing in 1994, when they traveled to Australia to visit their son, who was spending a year abroad studying at the University of Sydney. While there, the Wilkersons visited the Museum and Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin, where the collection features significant holdings of Aboriginal art, including work by Albert Namatjira, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, George Tjungurrayi, and Minnie Pwerle.

Completely unfamiliar with this material, the couple were astounded by what they saw. “The museum is circular, and John went one way and I went the other,” Barbara recalls, “and when we met up, I said, ‘John, I don’t like this, I love it’ and he said he felt the same way. We were hooked.”

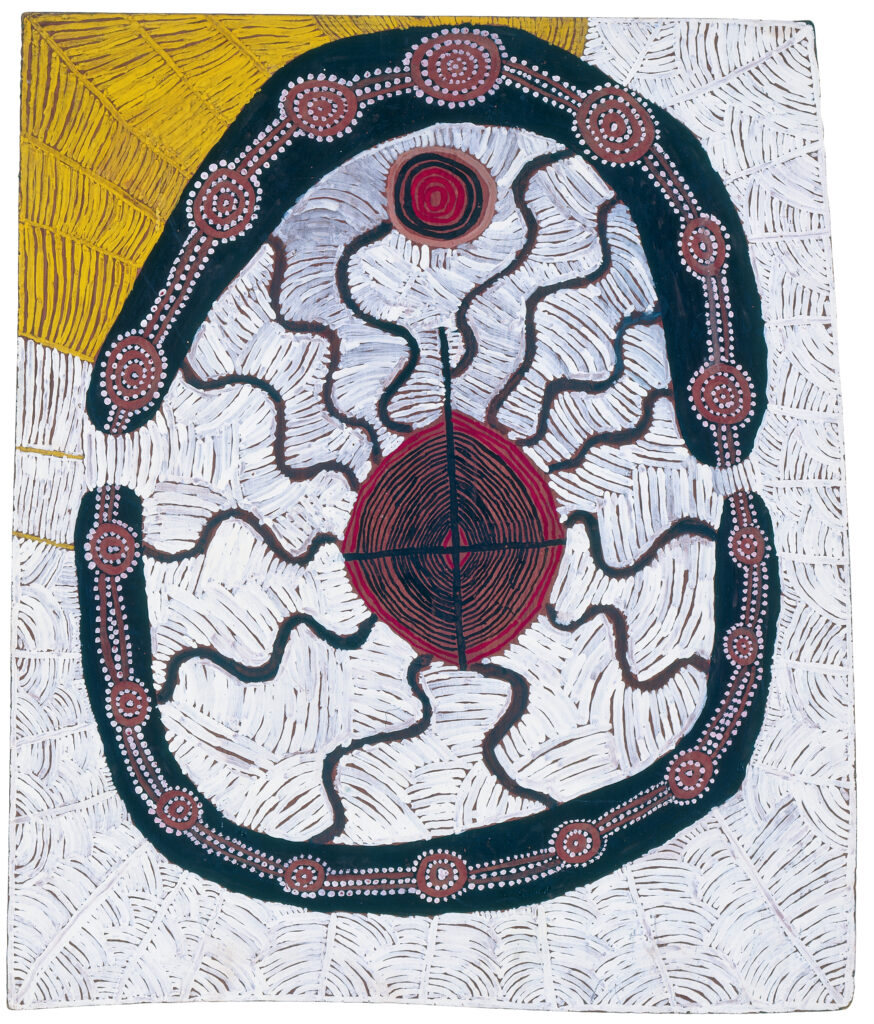

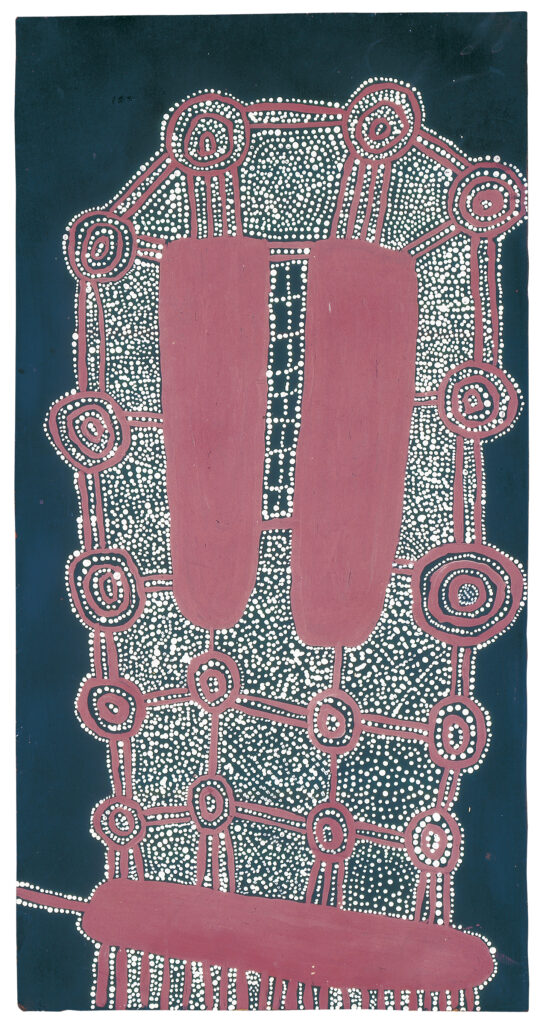

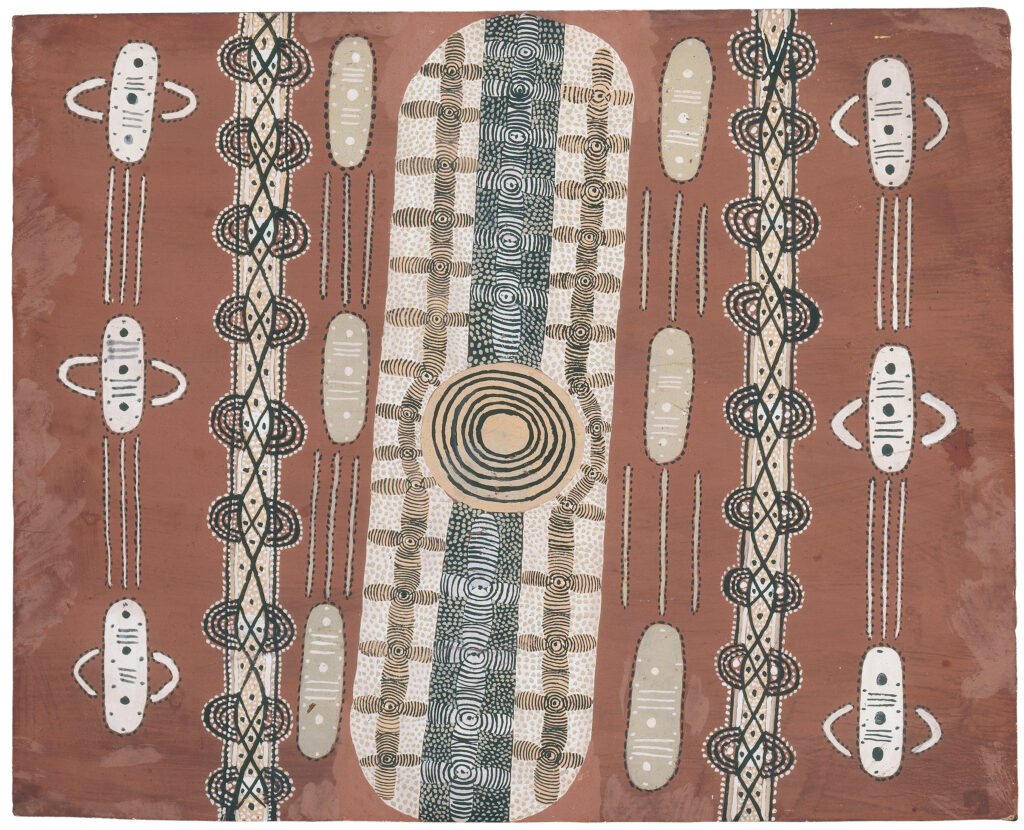

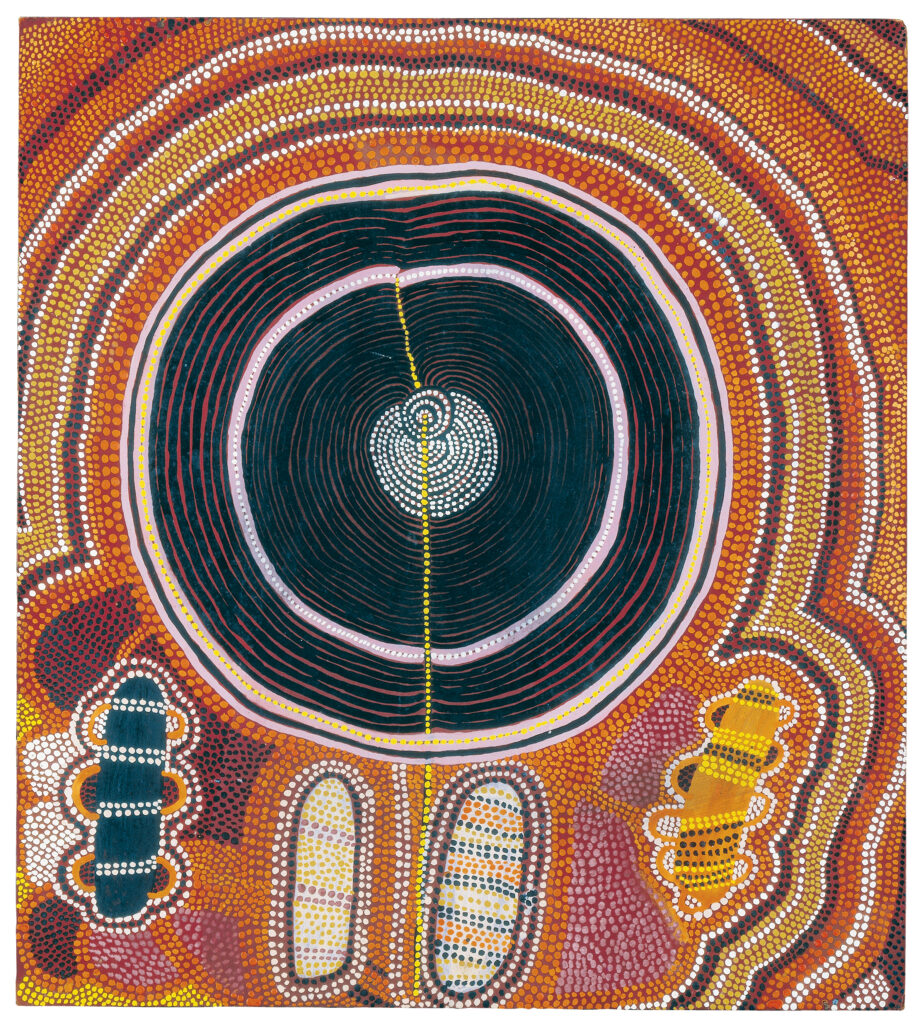

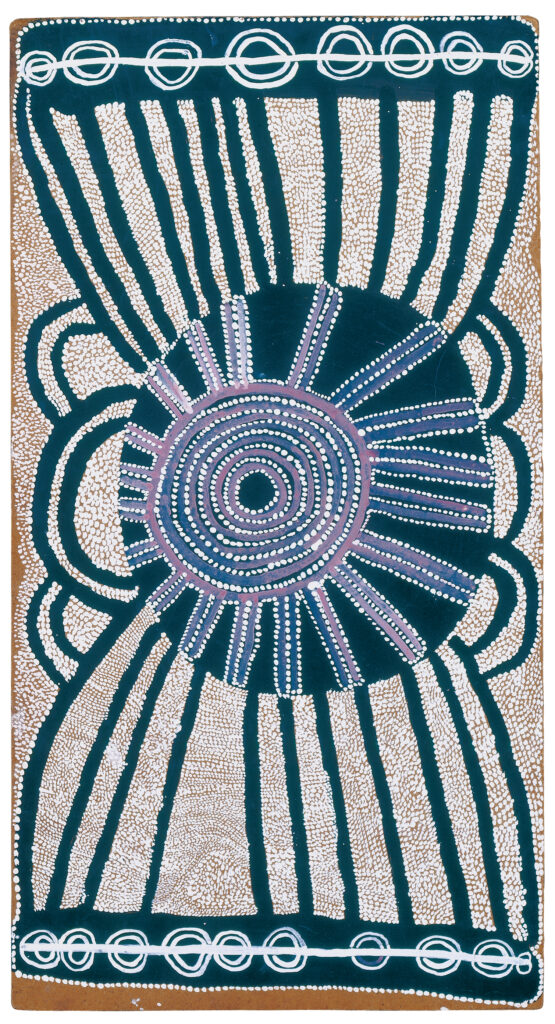

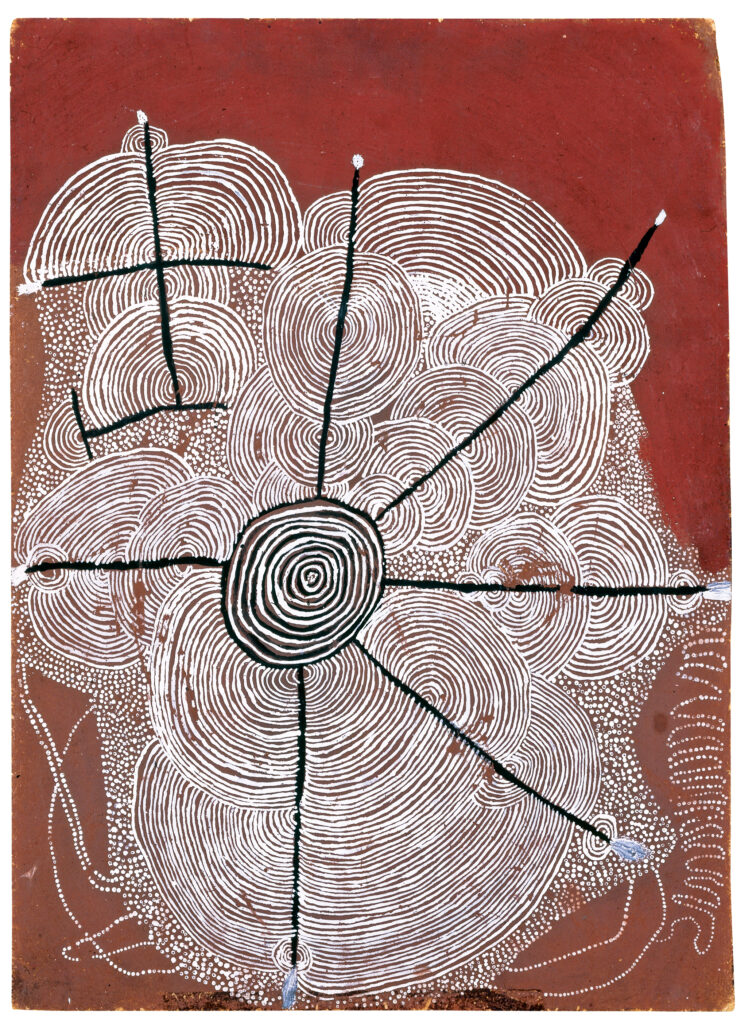

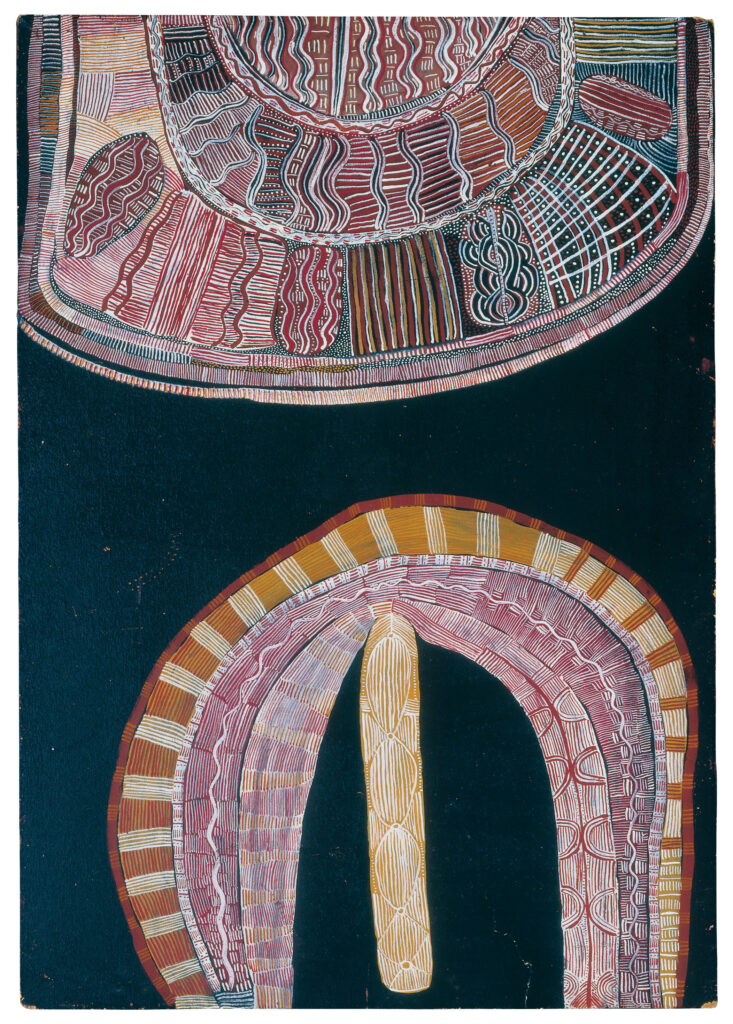

As with non-Western work generally, the art of Australia—that of mainland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—was historically viewed through the lens of ethnography and the narrative of primitivism. In the 1970s, scholars, academics, curators, and artists themselves began to break down that compartmentalization, situating these creative efforts more firmly within the context of visual art, while acknowledging the distinct values and cultural traditions embedded in the work. Playing a part in this perceptual evolution was the impoverished Western Desert community of Papunya, where, in 1971, an art teacher from Sydney encouraged senior male elders to create murals on the local school’s wall. The men then moved on to working with acrylic on Masonite. Within a year, hundreds of pieces were produced and many were marketed. The images created were spun from the profound Aboriginal attachment to the landscape, to place, to the ongoingness of past and present, a belief system known as “The Dreaming.”

This work helped propel the country’s growing interest in Aboriginal art (an appetite supported by the formation in 1973 of the Aboriginal Arts Board), and by the 1980s, thanks, in part, to acquisitions by Australian institutions, growing recognition abroad, and the marketing efforts of the artist-founded Papunya Tula Arts cooperative (which encouraged women to participate in art-making), the paintings achieved an appreciable profile, and some of the artists were able to make something of a living from their efforts.

In 1988 the paintings of Papunya artists, which came to include works on canvas, were included in the landmark exhibition Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. The show, which opened at the Asia Society in New York before traveling to the David and Alfred Smart Gallery of the University of Chicago, cast a wide net and featured acrylic work by Western Desert artists Judy Nampijinpa Granites, Theo Brown Jakamarra, Uta Uta Tjangala, and Tim Leura Japaljarri. The curatorial integrity of Dreamings did much to elevate the status of Aboriginal art. Inspired by the show, media mogul John Kluge went to Australia and bought or commissioned hundreds of works.

In 1993 he acquired the collection of University of Kansas professor Edward L. Ruhe, who had pursued Aboriginal art since 1965. Kluge donated his combined holdings—which includes significant Papunya Tula pieces—to the University of Virginia, where the Kluge-Ruhe Collection opened to the public in 1999. The legitimacy of Aboriginal art in the marketplace got a boost in 1996, when, under the guidance of Tim Klingender, Sotheby’s, Australia established its Aboriginal Art Department. Later, Klingender’s own firm—Tim Klingender Fine Art—was named Indigenous Art Consultantto Sotheby’s internationally, and oversaw auctions of Aboriginal material in London and New York.

The Wilkersons—who bought eight pieces on that first trip to Australia and later acquired a number of pieces at the Sotheby’s auctions—have focused primarily on the early years of the Papunya artists. “When we started collecting there were about twenty-five artists in this Papunya group,” notes John, a venture capitalist in the medical field who sits on the board of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. “Then over the years, the Australian government wanted people to develop a pride of authorship and they started funding art teachers to work with the Indigenous communities and so there was quite an outpouring of art and not much of a market. The Papunya artists have been consistent, but there have been what the Australians call carpetbaggers—people who saw an opportunity—who gave individuals canvas and paint and they just started pumping out art.

Today, you still have what might be called airport art, but you also have dealers, such as D’Lan Contemporary in Sydney, Melbourne, and New York and Salon 94 in New York that are committed to issues of provenance and connoisseurship and have created a very high-end position for the art.”

In 2009, a selection of the Wilkersons’ material went on view at Cornell University’s Herbert F. Johnson Art Museum (John earned his PhD at Big Red in 1970). Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya was curated by Roger Benjamin, Chair of Art History at the University of Sydney. Comprising forty-nine pieces, including works by leading Papunya artists Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, and Mick Namararri Tjapaltjarri, the show traveled to the Fowler Museum at the University of California, and the Grey Art Museum at New York University. A highlight of the exhibition was Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, an original member of the Papunya group.

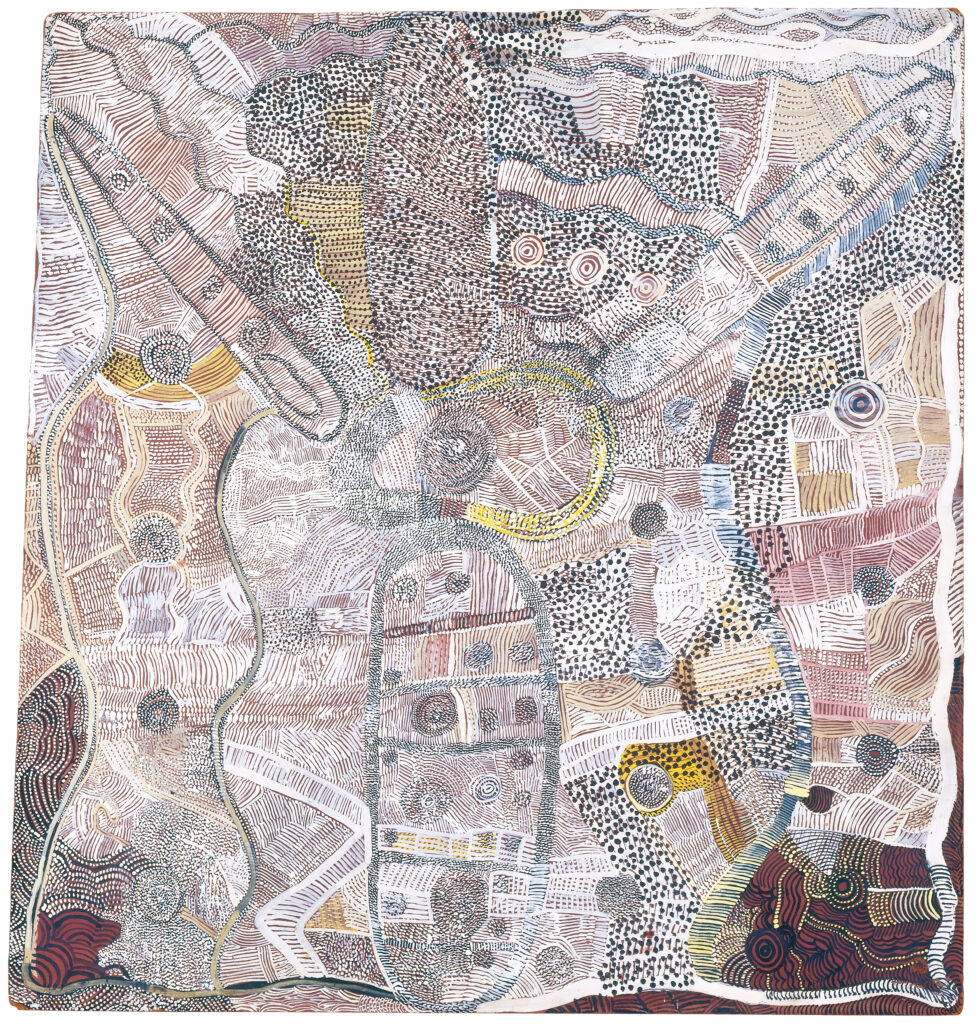

Executed in a synthetic polymer powder paint on composition board and measuring 313/4 inches by 293/4 inches, the work is a densely packed composition of dots, crosshatching, and undulating lines that reference a recent deluge, the ancestor that conjured it, and the uptick in plant and animal life that appeared in its wake. As the Wilkersons noted in the exhibition catalogue, “These artists were not just producing art to make a living, nor were they influenced by the art market fashion of their day; they were moved instead by a compelling need for creative expression.”

Internationally, Aboriginal art has certainly benefited from the more global outlook that has reshaped both the institutional world and the marketplace in recent years. In 2021 London’s Tate Modern presented A Year in Art: Australia 1992. The title referred to the year in which the High Court of Australia overturned a centuries-old ruling asserting that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples did not own the land they occupied. The exhibition contrasted the Western notion of possession with the Indigenous belief in the land as a living entity, not an asset.

Now, on this side of the pond, the National Gallery of Art in Washington is gearing up to present The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art (October 18, 2025–March 1, 2026). Curated by Myles Russell-Cook, former senior curator of Australian and First Nations art at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and current artistic director and CEO of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, it features over two hundred works by more than 130 artists drawn exclusively from the National Gallery of Victoria. The exhibition will travel to the Denver Art Museum, the Portland Art Museum, the Peabody Essex Museum, and the Royal Ontario Museum, all of which are participating in its organization.

Actor and comedian Steve Martin, a lifelong collector of modern and contemporary art had his own epiphany with Aboriginal art in 2015, when Salon 94 on New York’s Upper East Side gave artist Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri his first solo show in the US. Martin was taken with what he saw and bought. Since then, he and his wife, Anne Stringfield, have amassed an impressive collection of Aboriginal work. Along the way, they were introduced to the Wilkersons and in 2023, the couples drew from their respective collections for a by-appointment show at Uovo in Long Island City.

Combining the early work that centers the Wilkersons’ collection with the more contemporary pieces Martin has gathered, the exhibition offered a fifty-year overview of Indigenous art of the Western Desert. In a foreword for the Icons of the Desert catalogue, the Wilkersons wrote: “The three facets of our collecting philosophy have always been connoisseurship, scholarship, and education—we seek to bring together the finest examples available, to support original research to advance understanding of this art and the artists’ culture, and finally, to promote education by sharing the works with the public.”

Martin, who readily acknowledges the challenge of coming to a full understanding of Aboriginal iconography and the cultural underpinnings of Indigenous work, shares that conviction and is working with the Wilkersons to create a website—Two Collections—built on that triad. “The Wilkersons and I thought a thorough show of Indigenous Australian art would be powerful,” he relates. “But, logistics, cost, venue, and circumstances persuaded us that an online resource would accomplish the same thing, yet have a worldwide reach. Our site will be a place for scholars, collectors, dealers, museums—and fans—to compare and contrast these remarkable artworks.”