Clockwise from top left: Carleigh Queenth, Michael Diaz-Griffith, Emily Bode, Benjamin Miller

At the Winter Show’s 2019 sapphire jubilee, Curious Objects hosted a panel discussion with four young mavens of the antiques world—Michael Diaz-Griffith, associate executive director of the Winter Show; Emily Bode, designer and founder of fashion label Bode; Carleigh Queenth, vice president and specialist head of the European ceramics and glass department at Christie’s, New York; and Benjamin Miller, host of the podcast—in the Park Avenue Armory’s resplendent Herter Brothers–designed Board of Officers Room. They’d gathered to discuss the future of antiques, and to announce the birth of a community of interest called the New Antiquarians, which will champion antiques, historic art, and the material culture of the past.

Listen to the full episode above, or watch the discussion below.

Benjamin Miller: Hello and welcome to Curious Objects, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m Ben Miller. Today’s episode is something new for me—it’s a live special, recorded from the Park Avenue Armory in NYC. You’ll hear from a panel of young people in the world of antiques, including yours truly. We got together at the Winter Show, one of the foremost antique shows in the world, to talk about collecting, learning, research, craftsmanship, and the future of the decorative arts. We had a lot of ground to cover! This was also a launch event for a new group of young enthusiasts called the New Antiquarians. Stay tuned for more info about that.

On the panel are myself and my fellow organizer, Michael Diaz-Griffith, the associate executive director of the Winter Show; Carleigh Queenth, head of European glass and ceramics at Christie’s New York; and Emily Bode, designer and founder of the fashion label Bode, who repurposes vintage and antique textiles as contemporary menswear.

First a word from our sponsor.

Have you ever wondered who was the Master of the Embroidered Foliage or wanted to know what it was like to be at Andy Warhol’s factory? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, tells the stories of these and other curious objects. Discover Pennsylvania’s craft legacy, go behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, and uncover your passion for collecting. Visit freemansauction.com to sign up for their newsletter, and get these stories and more delivered straight to your inbox.

Michael would you please start us out by telling us a little bit about this group the New Antiquarians.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Sure. And first I’d like to welcome you all to the Winter Show. This is our sixty-fifth year. So you’re here thinking about the future of antiques with us during our sixty-fifth anniversary sapphire jubilee which I think is something very special. And you’re here because Ben and I began discussing an idea about a year ago. Right?

Benjamin Miller: I think it’s been at least a year.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Ok, two years ago. To try to convene young professionals in the arts and design around topics related to the antiques trade, the museum world—ll of the issues we face as young professionals in the field—in order to create a feeling of solidarity and a forum for a discussion about really the future of antiques, historic art, material culture—these fields that deal with history that we are really passionate about and that some think are on the decline. We don’t think they’re on the decline. We know from our experience that the future of antiques is bright and we kind of wanted a space to discuss topics around that future with other like-minded people. So that’s what we’re trying to kickoff.

Benjamin Miller: So here we are and this Herter Brothers’–designed room right in front of one of the great antique shows in the world. And I’m thrilled to see how many faces there are here. This is really just a delightful experience. Now, I want to kick-off by starting with the focus of what we’re all interested in, which is objects and that’s what all of this revolves around is the particular objects and the stories that can be told about them. And so just to start us off I wanted to ask each of the panelists here about an object that you have in your possession which is meaningful to you in some way. So, Carleigh, would you like to to start?

Carleigh Queenth: Thinking about the objects that are the most meaningful to me, personally . . . they seem to be objects that have been passed down through my family. So just the other day I was making cookies and I have a set of aluminum measuring spoons that belonged to my grandmother. And just using them now gives me a sense of generations past. Even though she was a terrible cook. I love things that have passed down through my family and those are the ones that I treasure the most.

Benjamin Miller: I’ve mentioned this on the podcast before but . . . I didn’t grow up in the antiques business I stumbled into it completely by accident. And so you know I wasn’t surrounded by antique objects as a kid. And I had to feel my way into what I like and what’s meaningful and important to me. And so one such object which I bought early after entering the business of antique silver, which is my day job, I bought a little teapot at auction which is just a little over 100 years old it’s not a particularly exciting or valuable thing. You know, it wouldn’t pass vetting at the Winter Show. I can’t hold you responsible for that, Michael.

Carleigh Queenth: It wasn’t ceramic?

Benjamin Miller: It’s silver. Yeah. So I do keep it polished and it’s . . . I wish . . . I should have brought it here, but it’s a bizarre combination of periods and styles and ideas. There are rococo elements there are deco elements. It was made by an American firm that never made hollowware they only made silver flatware. So this is far outside of their wheelhouse. They had no idea what they were doing and I just love the idea that somebody could, without any preconceptions, without any formalized training necessarily, come up with an idea for some new kind of object, something that hadn’t been in anybody’s life previously, and bring it into our lives. And now a hundred years later into my life.

Emily Bode: I feel like my object, I mean what comes to my mind right now is kind of a mashup between both of what you guys said. I’ve always wanted my family heirlooms . . . or, all of my heirlooms have been what I would have thought of, like my mother’s sweaters and my grandfather’s bowtie collection. But recently I bought my first quilt as part of my personal collection that I had read about. And it had been my iPhone background for I think about a year before I bought it. That act of buying something that I had loved for so long but it didn’t have necessarily like an heirloom quality in my own family kind of like sets it apart. It’s like the first time I cherished something that was not part of my family.

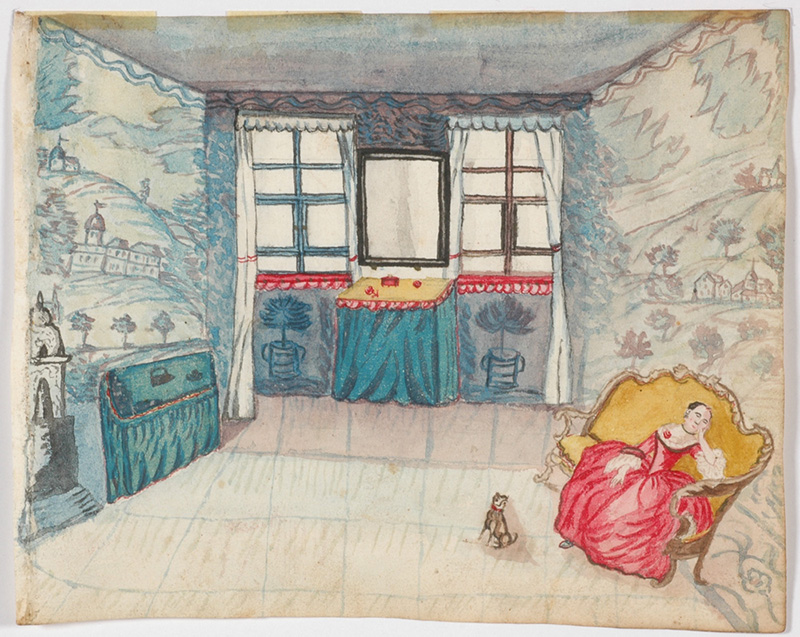

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Well I really connect to that because my mother’s mother was an antiques dealer and my mother hated her mother. So when she inherited a pink tractor trailer full of antiques from her she promptly sold them all. She hated that they smelled of smoke and they reminded her of her childhood. And so I grew up in houses that were filled filled with average suburban furniture. You know, things that my parents had gone out and bought because they were fashionable in Alabama in 1989 or 1994. So I didn’t have heirlooms because they had been cast . . . they’d been auctioned off, actually, and since I began collecting a few years ago I’ve been kind of constituting my own collection, something that I may pass on to my children or friends or family in the future. And one of my favorite objects I’ve spoken about on Curious Objects—it’s a watercolor.

Benjamin Miller: I love this picture.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: That I love. And it’s from a portfolio that was owned by a medical student in 18th century Germany. And what’s special about it . . . I mean, I just love the way it looks. And that really matters. You know, it gives me joy to look at it but it belongs to a family of watercolors that were spread across the globe from the same portfolio. And so I’m also a part of this kind of global family of people who’ve collected those sheets from the portfolio. And I just I love that . . . I love to think that while it would be lovely for that portfolio to be intact it’s kind of just as cool that all of these people share one piece of a greater puzzle.

Benjamin Miller: So, Michael, when you walk around the floor of an antique show like the Winter Show, what is it you’re looking for? What are you trying to find? Do you have galleries that you zero in on and go straight for, genres that you’re looking for? Do you wander aimlessly until something grabs your eye? How do you approach that?

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Well, I can’t be totally frank because we’re at the Winter Show, right? So I love all of the galleries equally. I love watercolors. They’re easy to collect. That’s something I’m focused on at the moment in my personal collecting but I just love that you go out onto the show floor and find decorative arts of the highest quality from 5000 years of human culture and history and one thing I’ve become really interested in as I attempt to speak to more and more young collectors to sort of find out what makes them tick is that while quality really matters—and it does and the Winter Show is a vetted show, so we care about quality, we think a lot about authenticity, date, condition at this fair—finding objects that just speak to you that are weird maybe or very, very particular to your sensibility and you know homing in on them, developing a relationship with the object and with the exhibitor who’s selling the object is kind of I think my focus increasingly and I think it’s the focus of other young collectors I speak to. There’s not a sense that, “ok I’ve started collecting one kind of material. Now I need to create a sequential collection where I build it in a particular way that someone else has told me is the right way.” Instead I find that if my eyes alight on one thing I begin learning about it, I begin listening to exhibitors tell me stories about it, and over time I develop my own kind of collecting narrative. And sometimes it’s really eclectic and it takes me from an object that was produced in Vienna in 1910 to a Biedermeier object that it was inspired by it and that’s what’s fun about the collecting journey.

Benjamin Miller: Yeah every object is a rabbit hole and you can dive down infinitely—sources of inspiration, materials, craftsmanship. Carleigh, what’s your experience? We were just walking around the floor and of course your area of specialty is ceramics. There are a few dealers at this show who specialize in ceramics and there are a lot of dealers who don’t. What is it . . . your professional life is completely full of antique porcelain and glass objects. Outside of work outside of your job, if there is such a thing, what do old objects mean for you? What niche do they fill in your life as you walk around the show floor here? What is it that draws your attention and what do you think about outside of Kangxi tankards and that sort of thing?

Carleigh Queenth: When I come to an antique show first I look for interesting objects. I love innovative displays and I really like the dealers to be friendly. I find that if you walk into a booth, especially for trying to get young people more engaged with these objects and find new collectors, and the dealers aren’t welcoming, it’s very off-putting. Whereas if you were taking the time to speak to them about something they were looking at and tried to show them what’s interesting or cool about it they might become a collector one day and you never know—somebody might have the money to spend now if you’d only taken the time. Outside of work, my poor husband has been dragged around the world. I feel like every holiday becomes a ceramic holiday, intentionally or not. I find a way to make it into a ceramic holiday. But it is because I really enjoy these objects and learning about them. So, yes, we’re traveling through Spain and “there’s a lot of historic houses that you can see” and “there is an amazing town museum in Lisbon” and there’s all sorts of other things that can really color a place. When I go someplace, I—

Benjamin Miller: And of course your Instagram followers are the beneficiaries of that because we get to see that.

Carleigh Queenth: Yeah. Yeah.

Benjamin Miller: I mean I feel like my . . . the boundaries of my exposure to your field expand any time you go on a trip because I see all the things that you’re looking at.

Carleigh Queenth: I love looking for the strange and unusual in ceramics and just pointing out things that people may not notice about more run-of-the-mill ceramics.

Benjamin Miller: Right. Emily, I don’t know, this is . . . you know, we’re talking a lot about objects and their histories. And aesthetics are clearly important and provenance is clearly important, but what you do with antiques is much more direct because you are actually a craftsman, if I can use that term . . . or you’re the one who’s taking the objects that we are all looking at and actually make making something new out of them. So I want to ask, Where did that idea come from? What was your inspiration for for working with these old materials as opposed to taking modern fabrics and trying to come up with designs that work for them?

Emily Bode: I feel like initially . . . I mean, I was raised going to antique shows and kind of having that connection started at a young age. My parents collected antiques, my grandparents collected antiques but it became more of like making from antique textiles probably in college. Every muslin, which is the first shape of a final garment, I was making out of fabrics that weren’t throwaways, essentially. So when I knew that I wanted to start my own brand I made a pair of trousers from a quilt top that I had saved—I had collected fabrics since I was little and I kind of had a collection already going—and when I made this first sample as a mockup I realized this is what got me most inspired. It’s creating a wardrobe for someone that has that intrinsic quality to it that you get from buying vintage or antique clothing or collecting antique objects but you can do it in a modern way. That’s kind of like initially where it came from. But my relationship to kind of what you were saying—a lot of what draws you to collecting are the people that are selling. It’s the dealers that I’ve known for years. And each collection that I do kind of is involved in one way or another with that relationship to another person.

Benjamin Miller: So let’s back up for a second, take a couple of those steps backwards, zoom out. Michael, tell us what what the definition of an antique is. Different people will obviously give you different answers, right? Legally it’s objects that are 100 years old or more. But I think colloquially that’s not really how most people use the term. So what does the word “antique” mean to you?

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Well, it’s funny you ask because today I was actually thinking about the word “vintage,” which we don’t discuss much around here because we’re dealing with material that is the best of the best to use the Winter Show’s old tagline. And traditionally that material has been antique material—100 years old or older—now that the shows dateline’s have expanded, our focus is on quality always and that means that we have to think about standards of authenticity of quality for material that may be 50 years old or 10 years old. And for me that’s really kind of . . . it’s opened up my way of thinking about objects because whereas before I thought about the disciplinary categories that the show works with—”porcelain has certain . . . the field has certain standards and are very important,” right, and we think if we’re thinking about silver we need to know our marks and there are very specific things we need to know about to comprehend that discipline. That’s what, you know, connoisseurship is, but as we look at objects on a more trans-historical timeline I think we can we can think about their intrinsic qualities in a slightly more creative way which is really what I think Emily is doing. So while I happen to love objects that are antique—I mean I’m passionate about the 18th and 19th centuries—I’m finding that over time my tastes are only becoming more and more open and eclectic and I think that that happens when you begin to really see objects and craftsmanship and artisanship for what it is and you begin to appreciate it in in all things no matter when they’re from. So the traditional definition of antiques still matters. We need to be able to think about why something is important because of the period in which it was produced because it has survived, because it has been valued over time. All of that is relevant. But I’m also interested in thinking about how a compelling object can matter whether it’s 10 years old or 50 years old a hundred years old or 5000 years old.

Benjamin Miller: It’s an interesting idea. Again, thinking about walking around the floor of the [Winter] Show, there are dealers who have a very clear specialty, who have deep expertise in one specific and well-defined area. And there are dealers who have two or three areas of expertise or specialty. There are also dealers whose inventory comprises objects of all different categories. And that to me is very intimidating. The notion that you can actually know enough about a wide variety of subfields to be able to buy and sell those pieces, to be able to identify fakes and forgeries, to be able to tell the difference between a B+ piece and an A+ piece. And yet sometimes those are also the most interesting stands to visit because you never know what you’re going to find and because you see objects juxtaposed that you would never have thought to put next to each other and after all that’s how we live, right? We don’t decorate our houses with just 18th century English silver. Maybe we should, but most of us don’t. And so to a certain extent we all—at least as collectors, I think—we have to have some notion of, at the very least, what we like across different fields and across different periods. And so I wonder, Carleigh, what are your thoughts about this? Because you are a person who has very deep expertise. And while I guess European ceramics and glass is actually a fairly wide range of objects . . . but you also of course see thousands of objects from outside that world every day. And so while I don’t know if you see thousands of those objects every day, you see plenty. Do you feel that your knowledge of these related disciplines or peripheral disciplines is enhanced by your study of your main field? Do you ever feel that you want to just leave the ceramics behind and go and learn about 18th century pictures or what . . . how do you relate to things that are outside of your your focus area?

Carleigh Queenth: Well I do love 18th century pictures, too. I think it’s nice to have . . . even if your focus is one thing—I love ceramics—I think it’s important to know the context in which those pieces were made. And so you can’t just know about the ceramics of the 18th century or the 19th century, you need to know about the social history of the period and about all the other decorative art that would have gone along with it. So you understand that, oh, you’re looking . . . you’d be looking at this plate and this chair by candlelight and this was going on in history and this is why the design is like that and all these sorts of things. So I don’t think you can look at it in a vacuum, I think you . . . I think even if you have a specialty you’re naturally curious about all the other subjects that surround it.

Benjamin Miller: Now . . . Sorry go ahead, Michael.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: I was just . . . I’ve been admiring on Emily’s Instagram feed—which is like my main way of knowing you until today—that your brand sells lassi cups, right? Like vintage lassi cups, and I was just wondering how . . . we know you for the way you’ve worked with quilts and textiles producing garments but your brand clearly encompasses, increasingly, a sort of broader world of objects. Can you speak to that at all?

Emily Bode: I feel like it’s . . . yeah, I mean that came from it was more so around the holidays and trying to have something that people could shop still in the world that we’re trying to evoke and create with Bode but not necessarily by a full garment. I think in terms of categories we’ve expanded in making other goods but it’s also I enjoy sharing those. Finding . . . that’s a dealer that I’ve bought from for awhile and I wanted to share those cups, which, they’re all engraved brass from like the 1940s. And to be able to share that story just as much as sharing maybe a story of fabrics is equally as important.

Benjamin Miller: Emily, how do . . . one of the interminable questions that we antiques and decorative arts people are constantly asked and constantly ask ourselves is “well, how are we going to make what we do appealing to new generations?” There’s a lot of talk of doom and gloom and there’s “we’re all going to go out of business,” right? And Michael and I don’t think that’s true. But I wonder how . . . we live in a in a fast-fashion world. Americans throw away enormous quantities of clothing every year. We don’t necessarily treasure our textiles in the way that people might have when textiles were much more expensive than they are today. And I think you could say the same about any number of types of objects that we have in our lives. I don’t need to mention Ikea. And so I’m curious the pieces that you make in some cases you can only make one, right? Right. Because you can’t just go order more of this 19th century quilt. So how is it that . . . how how does what you do sort of compare with that world or fight against or play alongside the world of fashion labels that are trying to turn over our wardrobes as quickly as we can?

Emily Bode: Yeah. Initially . . . I mean, the foundation of the brand was dealing with just antique textiles and I hadn’t realized that we don’t store domestic textiles like our parents or even our grandparents are. There are quite a bit of them you know there’s linen closets full of embroidered linens and bedsheets. And that’s . . . we continue to make the antique, one-of-a-kind pieces. But in terms of scaling our business we’ve begun to embroider them in India and make our own patchworks. And that’s one aspect of becoming a part of the fashion industry as a whole in that sort of sense. And then it’s, to me it’s more about making individual objects. That’s what was so attractive to me about these antique pieces and making one piece that people would buy into and pass along and save and keep it or call as heirlooms that are in a timeless shape. So it’s not necessarily following fast fashion and trends. It’s could be trendy, but it’s more about creating garments that you could put on a guy in the 1940s and not be able to tell if, like, what era it’s from still today. It’s kind of . . . the silhouettes are . . . speak more to like the timelessness.

Benjamin Miller: Right. I mean, I just love the idea of being comfortable with the daily use of old materials. And it’s something that, as a dealer, I can’t tell you the number of times someone comes into our shop or walks onto our stand at a show like this and says, “I could never use that tankard.” And I say, “Yes you could. And if you buy it I hope that you will.” Because after all that’s what it’s for. That’s what it was made for. That’s the whole point of it and . . . which is not to say there aren’t objects that belong behind glass and that are too rare or too delicate and too important and need special preservation and whatnot. But generally speaking the analogy I sometimes use is is that to put, say, a tankard behind glass and not use it is much like closing Notre Dame to worshippers because it’s too important as a historical monument which would just suck the soul out. The whole reason that building is interesting is that it’s been in use for 800 years. And similarly you take that tankard out from behind the glass you put some beer in it and suddenly you’re sharing in this 100 300 400 year lineage to be a part of that I think this is a really special thing and for you that’s what you’re bringing into people’s everyday lives.

Emily Bode: I mean, a lot of it is explaining to our customers you’re not supposed to buy something, wear it once, or to mend your clothing and to keep it. Same thing. You know you can’t be scared that you’re going to destroy something it’s . . . we have some people that buy it and store it. Or they hang it on their wall. They just love it as an object. But for the most part it’s kind of teaching people to buy clothes in a way that you mended and you can repair it and you can patch it if you have a stain or if there’s a tear you know it’s not finished. If you feel like it’s overused or something.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: I mean it’s in that sense it’s about sustainability as well as all of the sort of historic connections we’ve been making.

Benjamin Miller: I keep hearing about this bumper sticker that says “Go green—buy antiques.”

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Yes, yes.

Benjamin Miller: I don’t know how true that it is.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Depends on how many times you’ve shipped them.

Benjamin Miller: Let’s take a quick break. Before we hear again from our sponsor, I just want to thank everyone who’s reached out with comments and ideas about Curious Objects. The more you tell me about what you want, the more likely it is I’ll be able to make it happen. You can always email me at podcast@themagazineantiques.com, or find me on Instagram @objectiveinterest, where I also post pictures about the podcast—you might want to see the beautiful room where we had this panel, for instance. You can also help by leaving a review and a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening right now. Thanks so much! We’ll get back to the conversation in just a minute.

Would you like to learn how much the most expensive American looking glass ever sold at auction went for, or to find out if your collection is appropriate for sale? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, has the answers. Discover how Thomas Eakins’ Gross Clinic stayed in Philadelphia, delve into the work of Wayne Thiebaud, the great draftsman, and much more on their website, freemansauction.com. From modern masters to French furniture, Freeman’s takes you behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, delivering the latest in art market news, events, and stories. Subscribe to their biweekly magazine, and get it sent straight to your inbox. Visit Freeman’s at freemansauction.com to learn more.

Carleigh, you are . . . you’re in the fast and loose world of auctions. There are as we all know there are trends, there are things that become exciting to the public and to collectors and then there are things that seemed to die out. I’m not going to name any names but you know. Well, I’ll name a name. So. We all have heard tales of the demise of brown furniture. Now I think this is great news because I love brown furniture. And if it’s cheap that means I can afford to buy it. And in fact I’ve said that if I had a few million bucks to spare right now I would buy a warehouse and fill it with 18th century English furniture because I can’t really think of a better investment. And in the meantime I get mahogany sideboards and tables and things. But the market is depressed. On the other hand the market for contemporary American art is exploding. We could go through a list of a hundred different fields and each one has its own trends. Are these trends? Or is there a cycle to them or are they cyclical or was brown furniture going to be dormant and have a resurgence in the next decade? How do you think about those things?

Carleigh Queenth: I think it is a cyclical and I think it’s rising like a phoenix from the ashes.

Benjamin Miller: There are some hopeful signs.

Carleigh Queenth: There been very good signs. Brown furniture—and we’re talking about English furniture—did very, very well at our David Rockefeller sale last spring. We had a sale of the Lyall Collection last week and that did very well. I think some people just need a guiding hand on how you live with these things. And I think we’re coming back and I’m seeing more decorators using these types of objects. I love what Miles Redd and Alex Papachristidis and the other interior decorators are doing, mixing old with new. I love how at the show they have these fresh modern wallpapers with the English furniture against it and it really makes it come alive. And it’s not like you’re sitting in a stuffy period room—you could actually see it in your living room and looking really cool.

Benjamin Miller: And who are the tastemakers? I mean who decides what’s going to rise and what’s going to fall, aside from us in this room?

Carleigh Queenth: I think it’s interior decorator, design magazine, and people on Instagram.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: And this is where I plug our dealers again at the show because we’ve framed them as storytellers and experts and they are but one of one of the most compelling things about this year’s show is the dynamic way in which our exhibitors have presented the material, and I know that Carleigh was talking about this on the show floor and she has in this room . . . for someone who has the highest level of expertise in 19th century painted furniture or 18th century English furniture who really knows their stuff to also be able to say and look at it against this crazy Scalamandre wallpaper, look at how good it looks and look at how fun it is—is to me the most. I don’t know. There’s just nothing more compelling because you have all the weight of their scholarship and their knowledge. But all of the benefit of their eye and their taste which they’ve developed over the course of their careers while looking at the best material and also seeing the best interiors right. I mean it’s always at a show like ours about how you might live with the material even if museums are here buying, the majority of the buyers are still looking to incorporate this material into their own collections, into their homes. And In a funny way I feel like specialists have become some of the thought leaders in that in the world of design especially as it relates to how we might design with antiques.

Benjamin Miller: It is mostly the people in this room?

Michael Diaz-Griffith: And out on the show floor.

Benjamin Miller: And out on show floor. So, Michael, speaking of the people in this room what is . . . I’m going to ask sort of a double-sided question here: What is it that people of our generation don’t understand about the world of antiques that we should enjoy? The other side of that is what is something about our generation that the rest of the world of antiques doesn’t understand about us and should?

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Yeah, okay, so to take the first part I think it’s really simple. I think you can find high quality works that have fascinating provenance that are in great condition and that you’re in love with and I think you can you can buy them you can begin buying them now if you’d do your research and you talk to dealers and you’d go to museums and you learn the material you will be able to find buyable objects that you can begin bringing into your own life. And I think Carleigh works with a lot of material that you know any of us could begin collecting. And I love that about what you do. I know we could start talking about porcelain that I could probably . . . There’s a wide variety and I could lay it on my table next week. And I think that we have to begin thinking in that way. Right? In order to do what Emily is doing and to enfold these objects into our daily lives so that this is what we think about instead of Ikea or Crate & Barrel when we need new plates. And so that’s the first step.

Carleigh Queenth: And I don’t think people realize that what the price points are that you can have a 19th century dinner set for basically the same price as what you’re registering for at an upscale department store now or that you can have a very cool 19th century sofa at whatever interiors sales at the same price point as . . . I mean I don’t want to name names but like restoration hardware. We sell sofas for less than three thousand dollars and beautiful fabrics and 19th century woodcarving. And now I don’t think people realize that for the same price point you could have something meaningful and it could be a talking point in your home that is.

Benjamin Miller: And that will likely last.

Carleigh Queenth: And that is I guess you could say it’s green like you were saying. It’s a form of recycling. You’re a steward of a piece of furniture for a life and then it will move on to somebody else.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: And to answer the second part of your question and I’m going to try not to get into trouble here: I think that the greatest misconception about younger collectors were just you know younger people whom we hope become collectors is that they’re minimalists. False. 100 percent false. I think that the rising generation of aesthetes, people in the fashion world, people in the antiques world have a really . . . have an eclectic taste. I believe that in the depths of my soul and I think that we’re all a little bit traumatized by the Ikea wave by . . . I mean I love 90s minimalism OK and I love minimalist art. So this is an . . . I’m kind of using these terms in a loose way but to just use Ikea as kind of a base line. I think we’re all a bit traumatized by that look and about people sort of automatically moving to that 15 years ago as the baseline for an apartment.

Benjamin Miller: It’s college dorm rooms.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: It’s college dorm room and it’s over. And I I do think that there was a generation of people who rejected their parents antiques. I do. I’ve met so many people like my mother who just did not want to live with that material but to speak to what Carleigh said, I think that fashion is cyclical. I think knowledge is cyclical you know certain things are passed down some aren’t and they have to be rediscovered. And I think that you know not just the world of antiques but more complex aesthetic worlds and visual worlds are kind of being rediscovered right now by by younger people. And I think that that’s . . . we see that across music and fashion and the antiques world.

Benjamin Miller: Here, here.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: We’re not minimalists so. OK. Don’t be mad at me.

Benjamin Miller: Is anyone mad at Michael? I think that’s a good note to wrap up on. I want to open up in case there are any questions from the audience. Do you have a microphone or are we do . . . So if if there are any questions feel free to raise your hand and a microphone will be brought to you.

Audience 1: At the [risk] of being a martyr since I work in museum industry, do you think that museums have a part to play in our generation’s concept of antiques not being useful in the sort of do not touch philosophy that goes along with these historic objects?

Benjamin Miller: I think that’s a fascinating question and it’s actually a regret of both Michael and me that we don’t have a person from the museum world up here tonight. I do think that museums as with antique dealers are going through a period of readjustment right now where we try to figure out who our new audiences are and how to relate to them. And there is I think there is a sense in which previous generations might have been more comfortable approaching a museum with perhaps a more abstract kind of an eye. An eye to relating what they’re seeing to what they remember from their college art history courses and such that people of our cohort are . . . you know we want to know what these things mean to us. We want to know what the stories are. We want to be able to . . . and I don’t think that it’s about expecting us to know more than we know. In other words I don’t think that the problem is that we don’t . . . that young people aren’t sufficiently educated in art or art history or decorative art. I’ve been talking recently about this museum—some of you may know this—the Museum of Math which is down by Madison Square Garden. And they do this fantastic thing it’s organized as a children’s museum. But each little display which is usually some funky interesting kind of gadget has a little placard with a little description at a very basic level of what’s going on. But then you can move on to the more detailed version of that description. And if that’s not enough for you there’s an even more detailed version which if you have a PhD in math really tells you what’s going on behind the scenes and the the equations that are at play. And for me I find that a totally fascinating way of interacting with an exhibit because you can dive in as deep as you want. You can read the story in as much depth as you want, you can learn anything that you want to learn. It’s all there at your fingertips. And I’ve seen this at some art museums too. Not in exactly that way but, frankly, I love mobile apps where you can walk into a gallery and download information where if you forgot that art history lecture you know now you can actually do that deep dive. Gives you the context, gives you the story, it gives you something to relate to. So I don’t think that . . . I think that museums can certainly find and explore new ways of relating but I don’t think it’s a lost cause and I don’t think that there’s any reason not to forge ahead in those directions. What do you feel about this?

Michael Diaz-Griffith: I mean we’re at the Winter Show ok? So I would just say that one of the most exciting things about a fair like this is that you can see museum quality objects before they’re taken into private collections, whether they be the collections of collectors or museums and so not really looking at the big picture issues but just that what we can do today. I love that. If you go to the Winter Show or to Brimfield or to . . .

Carleigh Queenth: Auctions!

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Or to auctions because we’re all in this world together. You can touch objects you can feel them you can turn them over. You can engage with their material reality, with their surface in a very tactile way. And I think you know that our generation is interested in authentic stories. I think we’re also interested in tactility because we’re a digital generation that is kind of looking for other ways of experiencing reality. And that you know engaging with the art market allows one that kind of unmediated encounter with objecthood that museums have sometimes not allowed. I think increasingly they do. I think increasingly we’re on the same page. But in the meantime I definitely go to whatever venue will allow me to like turn things over and really get in there with the object.

Benjamin Miller: And make no mistake, as long as the Metropolitan Museum of Art occupies the most valuable real estate in New York City museums will always have a role as the focus of our cultural capital. So you know attendance is not exactly shabby at a lot of museums around New York City. So I you know similarly to the world of art and antiques there’s a lot of talking of doom and gloom about museums. I don’t know that that’s really the right attitude.

Carleigh Queenth: I think there are certain shows that really I don’t know brought 18th century objects or 19th century objects to life though at museums that have done a really nice job like this . . . a couple of years ago at the Met, I think it was a fashion show but it was in the 18th century galleries and there were like mannequins pushed up against each other like dangerously liaisons, smashed porcelain on the floor, and overturned chairs and it really sort of made the scene come alive versus when you just walk into a period room and everything is very staid. Sort of made you feel like you were in the 18th century. I also really loved the Dennis Severs museum for that reason. If you haven’t been in London it’s fantastic. You have to go through this historic house in silence at night by candlelight. And there’s remnants of punch in the punch bowl and there’s creaking floorboards and there’s an actual cat that lives in the house. It’s like lurking around and it really makes the period come alive and you feel like you’re moving through time in this house from the 18th century into the 19th century and you get this appreciation of what these things would have looked like by candlelight which you really can’t do in a museum or an auction house. It’s a really fantastic place and I think when you do make things come alive like that it makes more people interested and they want to know more. And I think there are ways that museums can make things come alive and be great and I think those are two good examples.

Benjamin Miller: We took a very long time to answer your question. Can we do one more question?

Audience 2: Hi, thank you so much. So my name is also Allison Vicenzi I’m a clothing designer and as of tonight I’m a New Antiquarian. Thank you. I’m excited to get a little bit more about exactly that means. I was wondering just touching upon the last point that you brought up in the conversation about how price accessible antiques are and how many people would be surprised to hear that. I’m just curious for those who maybe aren’t in this room and don’t or are overwhelmed by the thought of hunting for antiques, are there any specific resources that you recommend sharing both in person or online where you can find say homewares like just to narrow in on a focus like homewares where people could browse, shop, get it delivered maybe? Like even I’ve . . . because I’m trying to convert people basically friends and things like that. And I think even like an entry fee to a fair is sort of one barrier that may get in the way which is . . . seems foolish because in the end you’re getting a great deal on a unique item. But just curious if you’ve come across any resources that minimize the barrier to entry for those just getting started. Thank you.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: I feel like you have a really interesting shopping life.

Emily Bode: Definitely going to outdoor markets. I mean it’s weather . . . like in the summertime I’m going to Brimfield knowing kind of when to go takes a bit of time. Like a few times going. And I think when I first started going to auctions that changed my life. I didn’t know that I could just go to an auction. And also making appointments with people. To get yourself comfortable with reaching out to people on direct message that you like their collections and private people who you would otherwise be scared to talk to is important to share and say like everyone’s open to taking a meeting even if they’re not sure you know how much you can spend and it’ll help educate yourself and also most of my contacts have come through my network. So it’s once I meet with one dealer at an outdoor market he’ll give me a whole slew of contacts all over the nation or in Paris or just creating that community and communication I think is really important.

Benjamin Miller: Absolutely, yeah. I mean I think that many many auction houses are making it easier and easier to explore their collections. So I’m you know I spend a lot of time of course just in my professional life scouring the auction houses but I also spend time looking through auction listings for things that might be of interest to me. I might look at a thousand things before I find something that I actually want to bid on. But the other 999 are all teaching me something at the same time and it’s kind of fun.

Carleigh Queenth: And if you’re looking for something very specific too a lot of auction houses—Christie’s we do and also on Live Auctioneers—you can say what you’re interested in finding out and it will alert you if something comes up which is helpful if you’r looking for something specific.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: Right. I mean that matters right? If you can’t pay thirty thousand dollars for the set of plates that we were discussing earlier you can really narrowly specify what you are willing to pay.

Benjamin Miller: Although I would say you should probably look at the 30000 dollar plates to just see you where you are—

Michael Diaz-Griffith: And that’s where the Winter Show comes into the picture for younger buyers. We have this initiative on our Young Collectors Night now of marking objects at ten thousand and below 5000 and below 3000 and below. And for someone who’s maybe 40 or 45 or 35 who’s highly qualified that’s an entry point and that’s great. And we’re trying to point out to them that OK everything here isn’t a half million dollars or a million dollars. There’s an object over there that’s 2500 or 5000 and that’s one entry point. But for someone for whom that’s not an entry point the show is an education for the eye. Right. And it’s the sort of classic connoisseurship test of you know good better best. Right. So even if I’m collecting just at the good level from my own personal use at home I need to know what’s better and what’s best not from the perspective of taste but from the perspective of quality or craftsmanship. I need to know what’s out there in the market and what the range is and you know it means that whatever your budget is it’s never the wrong time to go to the Winter Show. It’s never the wrong time to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to learn about an area that you may be interested in collecting.

Benjamin Miller: And it’s worth thinking about what these objects might be worth to you. Because I think some you know one thing that I continually hear from people of previous generations. We call them . . . that is that young people want experiences they don’t want objects, they want to travel, they don’t want to clutter up their tiny little apartments. And that’s all well and good but for me that’s not how I experience antiques at all. Because for me they are experiences. They’re experiences that I have every day. And if I can spend the amount of money that I would spend to take a weekend trip to some little B&B somewhere and instead buy a silver teapot that I can use every day which every time I use it it means a little more to me because I’ve been building a relationship with it and an understanding of it then that’s a tradeoff that I think I’m very willing to make. And that I would make again and again and again.

Carleigh Queenth: I think even if you’re not trading vacations, even if you’re buying a dinner service from the 19th century that costs as much as wine that is new that’s an experience. And it’s sort of a travel back in time. Every time you use it and when you have guests or friends over you get to bring them into this experience as well and that creates a talking point when you get people over. It’s great.

Benjamin Miller: All right. Well thank you all so much for coming. This has been a lot of fun. Thank you to Michael for helping to organize this and for participating. Thank you to Carleigh and to Emily thank you to the Winter Show for hosting us in this beautiful room. Thank you to The Magazine ANTIQUES for making this whole thing possible. We will be milling about. I hope you will too. Have a good evening.

That’s it for this episode. Hope you enjoyed it. Today’s episode was edited and produced by Sammy Dalati, our music is by Trap Rabbit, and I’m Ben Miller. I’ll catch you next time.

Rococo interior scene attributed to I. F. Zeidler, c. 1750. Watercolor on paper, 5 5/8 by 7 1/8 inches. Collection of Michael Diaz-Griffith.

Michael Diaz-Griffith (@michaeldiazgriffith) is associate executive director of the Winter Show, and co-founder of the New Antiquarians. Involved with the Winter Show since 2014, when he served as staff coordinator, Diaz-Griffith is committed to introducing art and antiques to a younger generation of collectors and is focused on expanding the show’s audience. He received his bachelor’s degree at the College of the Atlantic in Maine, his master’s from King’s College London, and holds a graduate certificate in fine and decorative arts from Sotheby’s. He is a member of the American Young Georgians and of the Victorian Society in America.

Aluminum measuring spoons, American, 1950s. Collection of Carleigh Queenth.

Carleigh Queenth (@breakingisbad) is Vice President, Specialist Head of the European Ceramics and Glass department at Christie’s, New York. She began at Christie’s in 2004 and specializes in eighteenth and nineteenth century European ceramics and Chinese export art. During her tenure she has worked closely on the collection sales of María Félix, Benjamin F. Edwards, Robert Hatfield Ellsworth, Richard Melon Scaife, President Ronald Reagan, and David and Peggy Rockefeller among others. She is a board member of the American Ceramic Circle, the French Porcelain Society, the Majolica International Society, and is an Attingham Summer School alumna. Her Instagram account exclusively promotes historical and contemporary ceramics and has been featured in Vanity Fair (UK, November 2018) and Homes & Gardens (UK, March 2017).

Beaded Tab Jacket made from a mid-century wool blanket and adorned with 1950s children’s beads. Courtesy of Bode.

Emily Adams Bode (@bode) was born and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. After studying in Switzerland, she moved to New York and graduated from Parsons School of Design and Eugene Lang College with a BA/BFA dual-degree in menswear design and philosophy. After gaining inspiration while working for brands such as Ralph Lauren and Marc Jacobs, Bode launched her namesake brand Bode in July 2016 with a menswear collection made from globally-sourced antique fabrics.

Silver teapot by Howard Sterling Company, Providence, RI, c. 1886-1902. Collection of Benjamin Miller.