Friedrich Hayek’s Nobel Prize medal. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The weighty thoughts and worldly goods of Austrian-born economist Friedrich Hayek are the subject of this episode of Curious Objects. A polarizing figure throughout much of the twentieth century, Hayek published critiques of the welfare-embracing macroeconomics of his English contemporary John Maynard Keynes, which endeared him to free marketeers like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan while earning him opprobrium from their left-leaning opponents. Now, Hayek’s 1974 Nobel Prize medal in economics and his personal dog-eared copy of The Wealth of Nations have come up for auction at Sotheby’s. Ben Miller calls on the expertise of Duke University professor Bruce Caldwell and Sotheby’s specialist Gabriel Heaton to put these and other items in historical context.

Benjamin Miller: Have you ever wondered who was the Master of the Embroidered Foliage or wanted to know what it was like to be at Andy Warhol’s factory? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, tells the stories of these and other curious objects. Discover Pennsylvania’s craft legacy, go behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, and uncover your passion for collecting. Visit freemansauction.com to sign up for their newsletter, and get these stories and more delivered straight to your inbox.

All right. Hello. Welcome to Curious Objects. Our subject today is Friedrich Hayek, born in 1899, died in 1992. He was an economist whose theory that market prices are an efficient mechanism for individuals to communicate information is a cornerstone of modern economics and led to Hayek receiving the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974. He was born in Vienna and split his career between London, Chicago, and Freiburg. In 1947 he organized the Mont Pelerin Society group of classical liberal economists who developed arguments against socialism. Although he once wrote an essay titled “Why I am Not a Conservative,” Hayek’s ideas about self-regulating markets have deeply influenced economic policymakers like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. He is often described as a countervailing force to the ideas of John Maynard Keynes. And there’s even I don’t know if you know this. There’s a YouTube rap battle between the two of them which is very entertaining. Hayek is one of the most widely cited economists of all time and now his personal effects are being offered for sale at Sotheby’s in London. To mark the occasion, I’m speaking with Gabriel Heaton a specialist at Sotheby’s who has organized the sale and Bruce Caldwell professor of economics at Duke University and the general editor of The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek. Gabriel why are these items coming up for sale now?

Gabriel Heaton: They’re coming from the family. And it is for personal reasons it’s an appropriate time for them to be to be disposing of them. But it’s all coming directly from them from the families from his descendants. One thing that we did that we did bear in mind and that has—and it did affect our timing here, somewhat—is that it’s the seventy-fifth anniversary of the publication of The Road to Serfdom in March of this year.

Benjamin Miller: Could you tell us a little bit about the marquee items of this sale? What is that object?

Gabriel Heaton: It is the key item in our sale is the original Nobel Prize, the medal awarded to Hayek in 1974. And like all of these prizes it’s a gold medal. Also there are a couple of other items that come with it. So they always have have a bespoke box and then they come they come with a citation with a telegraphic documents and then also color as well by a Swedish artist. Obviously, the key item is the metal but then you know there’s a small package of items.

Benjamin Miller: Now for those of us who have never received the Nobel Prize, how large how large is this piece and how much does it weigh?

Gabriel Heaton: It is about three and a half inches long. Solid gold. And it is engraved on both sides with the distinctive manner of the Nobel Memorial Prize for economics.

Benjamin Miller: Now we—

Gabriel Heaton: Each of the prizes have different engravings on them.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, I see. The value of this object . . . I would imagine is significantly higher than the value of the gold that makes it up. Tell us what you think this is worth.

Gabriel Heaton: We’re putting at estimate of £400,000 to £600,000 on the on the Nobel medal. Now that is very significantly more than the material content.

Benjamin Miller: Bruce, what was the key insight that the Nobel Prize was recognizing?

Bruce Caldwell: Well they recognized him for two contributions. Early in his career, he made contributions to monetary economics. This was during the period when he and John Maynard Keynes engaged in the battles that are represented in the rap video that you mentioned and the other contributions that the Nobel committee identified was his contribution to social theory. He got the Nobel Prize together with Gunnar Myrdal who was a much more left-leaning. So they had one Nobel winner who was a free market advocate, the other one who is an advocate of the planning of various sorts and government intervention of various sorts. But both of them in addition to being economists had written in areas outside of economics. Hayek had contributed to political philosophy with books like the Constitution of Liberty or Law, Legislation, and Liberty. He contributed to social science methodology. He actually even had a book called The Sensory Order. That was on theoretical psychology. So they were recognizing the Nobel committee was recognizing the fact that here are two economists but they were economists who did something more than economics, that they tried to study social and cultural and political aspects of society in a way that a straight economist who’s simply building models of the economy . . . going beyond that sort of contribution.

Benjamin Miller: Gabriel, how do you determine the value of an object like this? You said £400,000 to £600,000—where does that number come from?

Gabriel Heaton: Well, the value of Nobel Prizes is very much in the in the recipient and really where the recipient sits in our culture today and how much he or she means to people. They do vary enormously in value and they are—it is quite hard to predict how they will how they will perform at auction. But Hayek is someone who has been so key to a kind of economic and political force in recent decades and is cited so much. By a range of people. And this is very much at the heart of the end of a kind of economic and fiscal movement that has been hugely influential. So. That’s why we think that he is someone who will be really treasured by people so that there will be strong competition for what is really the ultimate public accolade for his thoughts.

Benjamin Miller: If it does sell in the range of your estimate is that, will that be a record for a Nobel Prize or are there others that have gone for even more?

Gabriel Heaton: There are others that have gone for even more. The the record is the James Watson Nobel Prize which sold for I think it was around $3 million. They’re not very easily comparable.

Benjamin Miller: Now, Bruce, as Gabriel insinuated earlier, Hayek is a politically-charged figure and is sometimes associated with various political controversies. His career, I think it’s fair to say, was defined, at least as we see it, by intellectual debates. What was the nature of those debates? Could we dive into that a little bit deeper? What are the controversies that define Hayek as an ideological figure today?

Bruce Caldwell: Sure. I’ll do a little self-promotion and let you know that if there are people who want to know more about Hayek in a very painless . . . I gave a talk that was taped at Clemson University and it’s on my website at Duke University about the life and times and ideas—contributions of Hayek. But you’re exactly right. This is a person who is of interest to me as a historical figure because he seemed to be at the right place at the right time, but he was always fighting with the people that he was around. So in the early 1930s he had the debate with John Maynard Keynes about what the appropriate policy should be in terms of dealing with what would be called macroeconomics, the macro economy today. He also engaged in debates with people who were favoring socialism. There has been an increased interest today in democratic socialism. Well, he was debating people at the London School of Economics and elsewhere on the merits of socialism in the 1930s. It was in the process of those debates that he came up with the idea of how a market system within an appropriate set of other social/juridical/political institutions is a remarkable device for coordinating economic activity in a world in which knowledge is dispersed. That would be a phrase that could be used to describe it. He also talked about what he called spontaneous borders. These are complex phenomena—theory of complex phenomena is something that he wrote about—and this is something that goes indeed far beyond economics. His work in psychology was also looking at how the interaction of individual agents can sometimes create structures that are much greater than—and unintended structures—that contribute to whatever phenomena you’re looking at. So, for example, within the brain we have individual neurons that are firing. They’re not trying to accomplish anything but the end result of all that is is human consciousness. In in a like manner, the working of individual agents in a market—nobody intends to feed Paris every day, you’ve got millions of people, though, whose work, either from directly feeding people through restaurants but also people who are bringing food to market are growing the food who are miners whose end products end up being silverware—all of these people are contributing to feeding Paris every day although no one plans to do it. Those are the sorts of things that he was examining and it’s why actually his contributions are viewed as . . . although there’re, as you say, obviously there are political elements that are tied to this. But his understanding of how a market system works and what to do when it fails to work I think are quite insightful. Among the other Nobel Prize winners in economics I saw one paper one time by a scholar named David Skarbek that said of all of the Nobel Prize winners in economics the ones who cite other Nobel Prize winners in economics in their Nobel addresses, Hayek was at the top of the list of people who other people cited. So that gives you some sense that he is not really just an ideological figure although he’s been embraced by certain groups in various ways. He’s a real scientist contributing to the science of economics.

Benjamin Miller: For someone like Gabriel or I who is not a professional economic historian, where might we look to see the effect of Hayek’s work and ideas in today’s politics and economy.

Bruce Caldwell: So as you’ve pointed out he has a paper that said why I’m not a conservative. So he is somebody who believes in free trade, so those who would argue for protectionism he would oppose that. And indeed, in 1945, he had written his most famous book, The Road to Serfdom, and he came to the United States thinking he was going to give a few lectures at universities and because the book went into a reader’s digest condensation they turned over the whole tour to a professional touring company. They worked them to death. He was going for a full month with multiple presentations. But he kept saying “look, I’m not a Republican.” The Republicans seemed to love him, the Democrats seemed to hate him, there was all of the same sort of political focus that we might have today and he would appear before a Republican audience and just say “look I just want to make sure you understand that this is not a partisan message. I’m for free trade for free borders.” The sorts of things that he would be for is the free movement of ideas, people, capital, goods. Throughout a country and across borders. At one point when he gave a talk before some . . . a Republican senator got in front of some of his constituents and the person who reported on the talks said “the temperature in the room went down 10 degrees” when Hayek started to talk about free trade because they were like “we like free trade but not for our industries. We want protection for our industries, but not free trade in general.” In very many ways he’s a mainstream economist in terms of his policy views, I would say.

Benjamin Miller: Now Gabriel, there are some other items in this sale. Could you run us through some of the more interesting pieces that are going to be available?

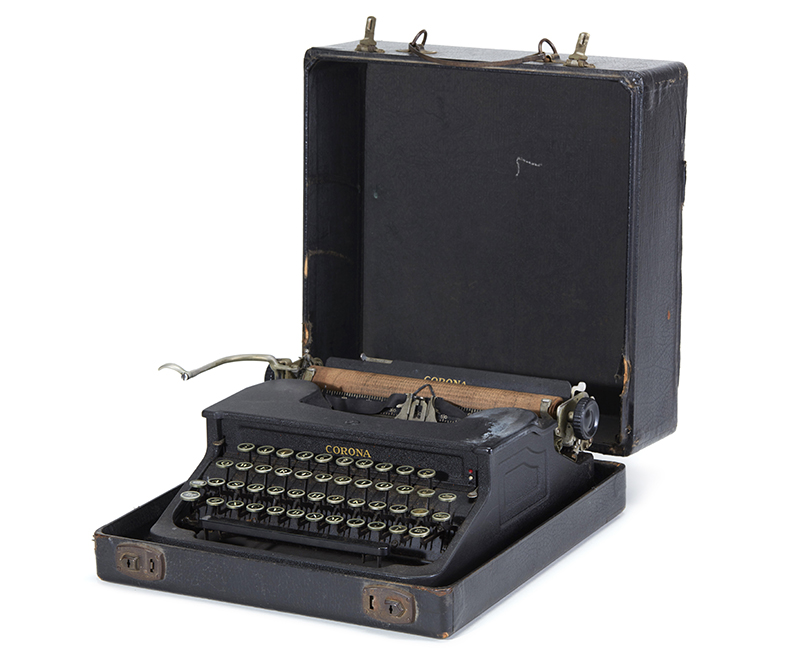

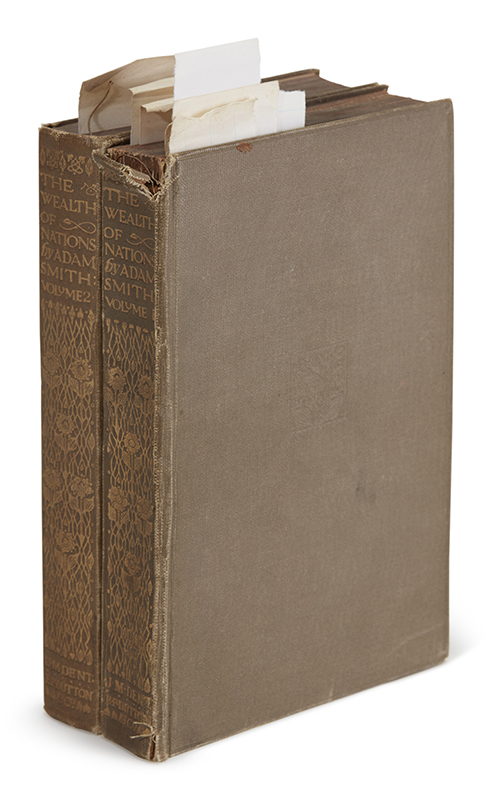

Gabriel Heaton: Well, I think my personal favorite would be Hayek’s own copy of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, which is a lovely. It’s everyman edition published in 1911. It’s not it’s not a . . . it’s not a valuable antiquarian book, but this is Hayek’s copy with his underlinings and the occasional marginal notes in there. It’s such an evocative object bringing these two great economists together. But there are other things as well. There are things like his his writing desk and typewriter, both from the 1930s, both almost certainly what he would have been writing The Road to Serfdom on. These are things from his LSE times. And we have . . . oh there was a lovely item you mentioned. Again, very very—in terms of individual value—very slight. But we have these gold coins that were stamped in the late 1970s as as a currency that did not have government backing very much that Bruce was talking about earlier. But these are Hayek’s. So it had his say face on them. And of course this is all very topical today because it’s basically a precursor of Bitcoin. So all sorts of treasures. And a few other books from his library. This sort of things. It’s a nice grouping of things; enough to give a flavor of the man. Actually another thing which of course does that would be photograph albums. So we have [unintelligible] albums of his which really they trace his traces life right through his . . . I mean, this is a man who grew up in . . . his childhood was spent in Vienna under the Austro-Hungarian Empire when it was one of the great cultural centers of the world. He then fought in the Austrian army in the First World War. He’s he’s in you know he leaves mainland Europe in the early thirties just before the rise of the Nazis. He spent the war the war in Britain. You know it’s really a pretty extraordinary life. And then in his old age he becomes this incredibly fêted public figure meeting presidents and the Pope and Margaret Thatcher’s favorite economist, famously said that There’s a long journey that gets into that place and items which trace that journey are really quite special.

Benjamin Miller: I wonder if you can say another word about valuing these objects. Let’s take his copy of The Wealth of Nations, for example. You mention that it’s the book that’s not particularly valuable from a collector’s standpoint outside of its association with Hayek. But of course it is associated with Hayek. Now as you as an auctioneer, how do you come up with an estimate for an item like that? It’s different from the Nobel Prize where there are at least comparables, other medals that have been awarded to other people and you can sort of go back and forth about who’s more important, but this is different, right?

Gabriel Heaton: Well, actually, the comparables to Nobel Prizes . . . they’re not really hugely helpful. I mean, they’re helpful in that there’s clearly—there are benchmarks there which show that there is no reason why a Nobel Prize cannot fetch really quite substantial sums at auction. But beyond that. They’re not. The comparables are not terribly helpful because they’re such. Different people who are interested in them and they’re interested in each of these Nobel Prize winners for different reasons. So, actually. Yeah comps don’t take you that far. And you’ve quite quite right with The Wealth of Nations. There are two ways of going about it. I mean you can value it simply as a book. And you say “OK, as a book this is worth”—actually in this case it wouldn’t even be this, but you say—”it’s worth a couple hundred pounds.” Put it in at that and then obviously you would expect it to go for significantly more than that because you let the market decide the value of the association. You can begin to think “well what do people pay for really good association books that kind of relating to economics and political theory.” And you reach an estimate that way. But you always want to be on the conservative side for these for these sorts of items. You do want to allow the market to operate and especially you want you want any auctioneer, you want competition. Because that’s what really gets you the best prices in the end is the strong competition between real bidders.

Benjamin Miller: What is the number that you put on The Wealth of Nations?

Gabriel Heaton: Sorry, it’s £3,000–£5,000.

Benjamin Miller: Let’s take a quick break. First, I want to remind you that as always, there are images of the objects we’re talking about on the web at themagazineantiques.com/podcast, and also on my Instagram, @objectiveinterest. And you can get in touch with by emailing podcast@themagazineantiques.com. I’d love to hear your comments and suggestions for future guests. Thanks so much for your feedback! If you like the podcast, leave a rating and a review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening. We’ll get back to Gabriel and Bruce right after this.

Would you like to learn how much the most expensive American looking glass ever sold at auction went for, or to find out if your collection is appropriate for sale? Freeman’s, America’s oldest auction house, has the answers. Discover how Thomas Eakins’ Gross Clinic stayed in Philadelphia, delve into the work of Wayne Thiebaud, the great draftsman, and much more on their website, freemansauction.com. From modern masters to French furniture, Freeman’s takes you behind the scenes at auctions and exhibitions, delivering the latest in art market news, events, and stories. Subscribe to their biweekly magazine, and get it sent straight to your inbox. Visit Freeman’s at freemansauction.com to learn more.

Benjamin Miller: Now there are other items in the sale and I mentioned the Mont Pelerin [Society]. Gabriel, there’s a piece commemorating that [society] in the sale, is there not?

Gabriel Heaton: There is. There’s a small gold ingot that was presented to Hayek in 1972 on the 25th anniversary of the of the conference which is a lovely memento actually of this key moment in postwar economic and political thinking and a nice, a really lovely gesture to Hayek.

Benjamin Miller: Bruce, can you give a little context around Mont Pelerin? What was it and why did it matter?

Bruce Caldwell: Sure. The Mont Pelerin Society was a meeting that took place in Switzerland in 1947. Hayek was the person who organized the conference. It attracted people who in later years would become famous, people like Milton Friedman, George Stigler. So these are members of the University of Chicago economics department, so the Chicago School of economics, as it were. And the way Hayek described the meeting was that he would go around to each country after World War II and there was such enthusiasm for building a welfare state. The Beveridge Report in England in the 40s that outlined the way forward. He said there was very few people who, like him, embraced classical liberalism, that were more in favor of a free market approach. So he gathered people from different countries all over Europe. This is postwar Europe. He had a few people from Germany but mostly the States, England, other places. And he saw it as a place where people who had similar views, although they disagreed with each other about the way forward, they agreed on certain basic principles—rule of law, trying to create a society where people have maximum liberty but also within a government framework as well. So they weren’t they weren’t anarcho-libertarians by any means, but they were going against the grain of their times. And it was it was in a sense that an intellectual discussion. And it was actually quite successful in a number of ways in providing an intellectual framework for developing some of the ideas that Hayek, for example, would express in books like Constitution of Liberty.

Benjamin Miller: So would you say it was influential in terms of, shall we say, the mainstream of economic thought in the latter half of the 20th century.

Bruce Caldwell: So it was interesting in the way that it was influential. It was quietly influential. A lot of people don’t know anything about the Mont Pelerin Society. It’s not like they put out discussion papers or anything like that. It’s a meeting of individuals. But the ideas that they generated certainly did enter into the mainstream. Particularly after the 1970s. You know, if you take a look at the economic history of that period you’ve got stagflation, that is to say, simultaneously high levels of inflation and unemployment, low growth, and this was following the tone of the rise of Keynesian economics where the idea was that government could manage the economy, have full employment with low inflation and exactly the opposite is what was taking place. So in England, in the United States, in other places these ideas suddenly had a resonance that they might not have had during the immediate postwar period. So it’s in that way that these ideas started to spread and then they had political representatives who would engage them. Often the theories and the politics weren’t always in line exactly. But certainly in terms of the general influence in favor of less government intervention of deregulation, that certainly caught on. And it is obviously part of an ongoing debate. Let me just point out that this was in 1972 so this was just when stagflation was actually starting to ramp up. So although Hayek early in his career favored a gold standard, later he did not and indeed later in the 1970s he wrote a book on the denationalization of money, competing currencies. But the idea of, remembering his contributions, the founding of the society by giving him this piece of gold was to say, “well we need to have a secure currency and the gold standard was something that at least at one time seemed to have worked pretty well.”

Benjamin Miller: Have you studied economic history at all before or was this a brand-new subject for you?

Gabriel Heaton: It was it was pretty much brand brand new. I mean you know obviously I was as I say, I was aware of him but I was aware of him really more from a . . . in terms of what I did know about political philosophy rather than rather than economics.

Benjamin Miller: Right.

Gabriel Heaton: But it’s one of the great pleasures of my job is to discover new writers, new thinkers, and to just try and understand what it is about them that makes them so compelling.

Benjamin Miller: And when the gears started turning and the sale started to come together, what sort of work were you doing to prepare for that and to . . . what sort of research were you conducting?

Gabriel Heaton: Well, it was a combination of things. So I needed to understand more about Hayek and what would draw people to Hayek, really, because I knew the politics with which he was associated, but what I didn’t know was how his . . . was about his thinking and how he reached the conclusions that he did. And what really struck me, what made me realize this is what draws people to Hayek is his questioning nature. It’s the way that he poses questions, really profound questions about the nature of society, the nature of economic transactions, he looks at these questions and that’s what takes him to the to the to the economic and the politics that we’re maybe more familiar with. That was the key thing to me. And then the other side of it was to look at the items that the family had and to sift through if you like to work out what would be what would be appropriate for auction, and that’s very much a collaborative business with the sellers.

Benjamin Miller: I want to step back from Hayek for a second and ask you about that can you give an example or two of other areas that you’ve been thrust into maybe without prior training or knowledge, and that you had to sort through.

Gabriel Heaton: Yes, it does vary a lot. I mean, what I do quite a lot of these very distinctive association objects, so items where the real, the value there is not in the in the object itself but that story that the object tells and so whether that could be Last September I was dealing with a copy of the novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover that was used in a very very famous trial, an obscenity trial here in England in the beginning of the 1960s, and this is one of the things that triggered the permissive society. I mean I’ve dealt with other Nobel prizes including the biologist Hans Kretz who discovered something called the citric acid cycle which is certainly something that I didn’t know anything about before.

Benjamin Miller: I thought everyone knew about the citric acid cycle.

Gabriel Heaton: I mean, it’s a wonderful pleasure to be to have that opportunity to find out about these very diverse subjects matters. And as I say it’s you know it’s not about becoming a great specialist in that area obviously, but it is, you know, it’s about understanding why people care.

Benjamin Miller: Who do you think—not specifically, but what sort of buyer or collector do you think is likely to buy the Nobel medal and what do you think that the piece is going to mean to that person?

Gabriel Heaton: I think it is very hard to imagine that it wouldn’t be bought by someone who is deeply interested in Hayek and for whom Hayek’s thinking does not mean a great deal. That’s really the key. That’s really key. That’s really the key point. It’s not about sort of someone who is a collector of Nobel Prizes you know. That is, it will be it’ll be someone who for whom Hayek chimes. It really, really means something to them. That’ll be the thing that sells the sells the Nobel. Who that would be we will you know we will have to wait and see. But what you can say is that there are a lot of people out there for whom Hayek does mean a great deal. Including people with substantial funds.

Benjamin Miller: Well Gabriel Heaton and Bruce Caldwell, thank you very much for joining me. I hope you had some fun.

Bruce Caldwell: I wish I had £3000 for the Adam Smith book. I’d love to see what Hayek underlined.

Gabriel Heaton: Yeah. Yes, it’s a lovely thing, isn’t it? Yeah, I think it will probably do very well.

Benjamin Miller: There you have it. Hope you enjoyed the conversation and maybe took something away from it. Once again, you can see images at themagazineantiques.com/podcast, or on Instagram @objectiveinterest. Today’s episode was edited and produced by Sammy Dalati, and our music is by Trap Rabbit. I’m Ben Miller. See you next time.

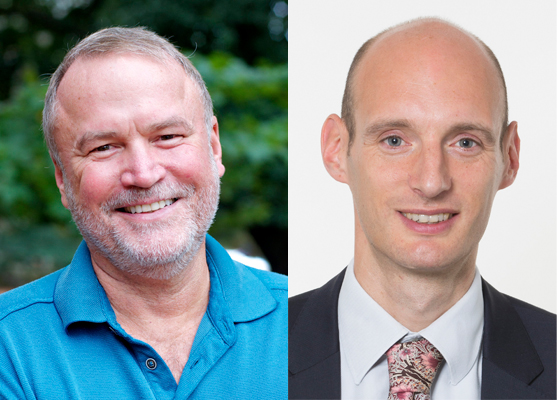

Bruce Caldwell (left) and Gabriel Heaton (right).

Bruce Caldwell is a research professor of economics and the director of the Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University. He is the author of Beyond Positivism: Economic Methodology in the Twentieth Century (1982), and of Hayek’s Challenge: An Intellectual Biography of F. A. Hayek (2004). Since 2002 he has served as the general editor of The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek. A past president of the History of Economics Society and the Southern Economic Association, Caldwell has held research fellowships at New York University, Cambridge University, and the London School of Economics. He is currently working on a full biography of Hayek.

Gabriel Heaton is a director and specialist in the Department of Books and Manuscripts at Sotheby’s, London. He was educated at the Universities of Durham and Cambridge and has worked at Sotheby’s since 2005, where he has handled major literary manuscripts by John Donne, Jane Austen, and Samuel Beckett; leaves from The Origin of Species and the nonsense poems of John Lennon; historical documents by figures from Elizabeth I to Mahatma Gandhi; and more unusual items such as an Elizabethan book of spells and Oliver Cromwell’s coffin plate. He has sold four Nobel Prizes in the past and is the lead specialist on Sotheby’s auction of Friedrich von Hayek: His Nobel Prize and Family Collection.

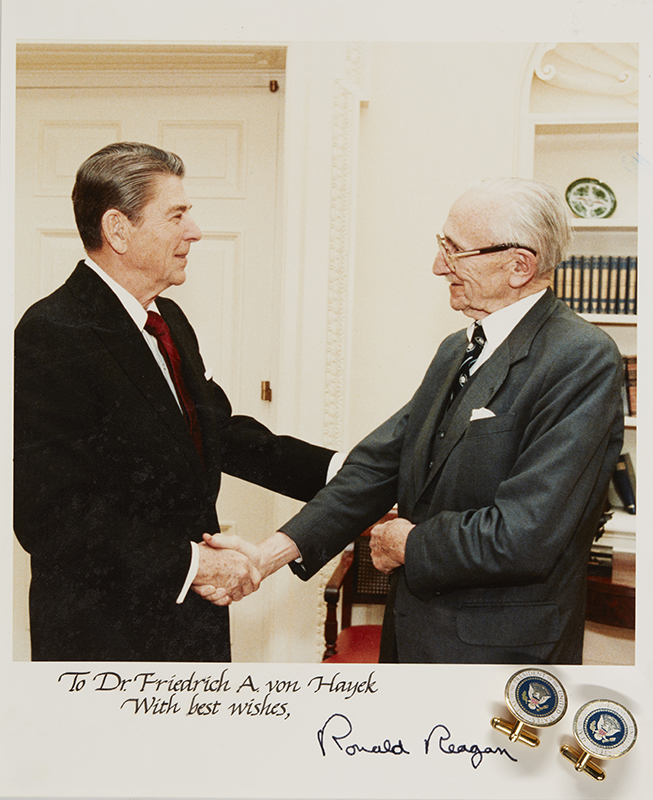

A signed photograph of Friedrich Hayek meeting President Ronald Reagan, and a set of presentation presidential cufflinks, from Reagan, with the Seal of the President on the front and signature engraved on the reverse. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Desktop ephemera and personal effects including 3 passports, a driver’s license, two compasses, one diary dated 1976, a Churchill Toby Jug, a bust of Adam Smith, and various other items. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Friedrick Hayek’s Smith-Corona Model S typewriter, manufactured c. 1933–1934. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The Wealth of Nations volumes 1 and 2 by Adam Smith, published by J. M. Dent, E.P. Dutton & Co., 1912. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.