Select one of the images to learn more.

In this episode of Curious Objects & the stories behind them, part one of a special two-part series, Benjamin Miller speaks with nine dealers who exhibited this past January at the antiques world’s marquee event: the Winter Antiques Show. Staged under the vertiginous barrel-vault ceiling of the Park Avenue Armory on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, the Winter Antiques Show is an annual showcase of some of the most interesting objects and artworks in the world, and Ben got the goods on such curios as a Pennsylvanian sideboard inlaid with 150 thousand minute pieces of wood; a diamond-headed, ruby-eyed serpent bracelet by Ernesto Pierret that looks poised to slither up your arm; and a spray brooch from the Russian crown jewels that’s big enough to grab attention even if you’re bundled like a Cossack about to brave the depths of a Siberian winter.

Listen to the full episode on iTunes, SoundCloud, or right here, using the SoundCloud plugin below. Don’t have time to listen to the complete episode? Pick an object that piques your interest from the grid above to listen to the segment of the podcast relating only to that particular piece.

Stay tuned: Next month we’ll be back with part two, which means many more curious objects when Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Nathan Liverant and Son, Stephen and Carol Huber, James Robinson, and Ben Miller’s very own S. J. Shrubsole, among others, bust out their mace-like molinets, Nantucket baskets, highboys, and five-legged card tables. You won’t want to miss it.

Benjamin Miller: Welcome back to Curious Objects & the stories behind them, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m your host, Ben Miller. Before we start, I’d like to draw your attention to America’s oldest auction house, Freeman’s. Located in Center City, Philadelphia, Freeman’s has been telling the story of valued objects and collections since 1805. Today, Freeman’s believes in a unique standard of one-on-one service, and their tradition of excellence has benefitted generations of private collectors, institutions, advisors, estates, and museums. Freeman’s is always inviting consignments, across all collecting categories. With furniture from Pennsylvania makers such as George Nakashima, Wharton Esherick and Paul Evans, and paintings of the idyllic Bucks County landscape by Pennsylvania Impressionists like Daniel Garber, Fern Isabel Coppedge, and Edward Willis Redfield, their Spring 2018 sales will celebrate Pennsylvania as a center for antiques, fine art, craft, and design. Let Freeman’s help tell your story; for more information or to set up a complimentary and confidential auction valuation, please visit Freeman’s online at www.freemansauction.com

Now, fasten your seatbelts. So far I’ve been talking with one expert per episode. Today’s show has not one, not two, but NINE different specialists. And there will be even more in the next episode. That’s because I’m bringing you on a whirlwind tour of one of the greatest antique shows in America: the Winter Antiques Show, at the Park Avenue Armory in Manhattan. This is a show that draws together, under one roof, some of the best antiques dealers there are, and once a year, in January, they bring with them the most rare, fascinating, and beautiful pieces in the world. So I had this incredible opportunity to interview some of the greatest antiques dealers in the world about some of the most curious objects that exist. They range from imperial jewels to Tiffany glass, to the finest American folk art and even a very political quilt. I’m so excited to share these stories with you. We’re going to be moving pretty fast, and if one of these objects really speaks to you, go take a look at its picture at themagazineantiques.com/podcast/. I don’t want to take any more time away from these experts, but don’t forget to subscribe to the podcast, leave a rating on iTunes, and send me your feedback and suggestions at podcast@themagazineantiques.com. Without further ado, here’s Patrick Bell with Olde Hope Antiques.

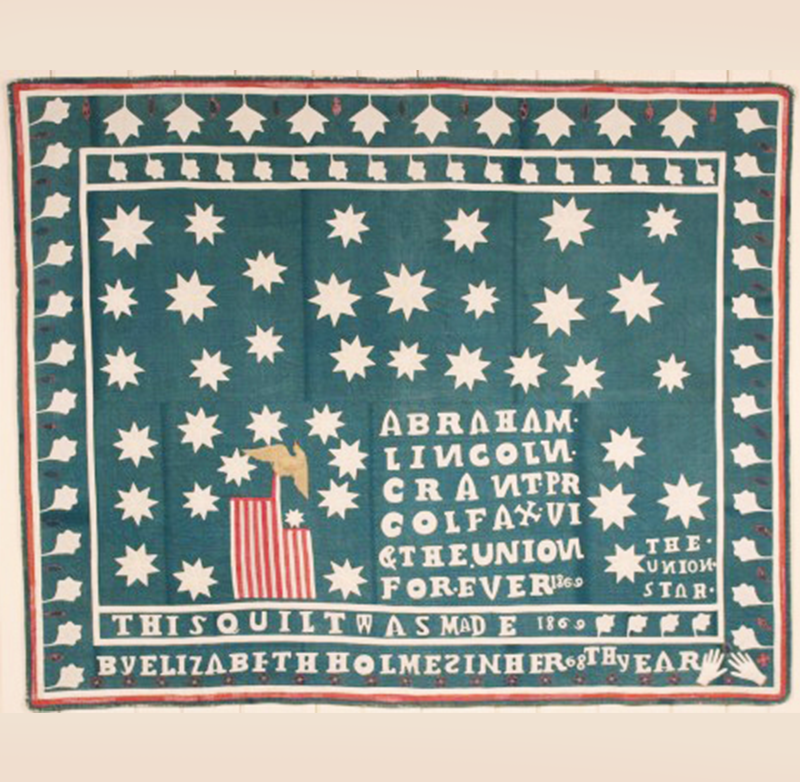

Olde Hope Antiques’s Union Star quilt

The Union Star quilt by Elizabeth Holmes, 1869. Pieced, appliqued, and stuffed-work cotton.

“She’s making a statement about America and the fact that the Union stayed together and she’s making an artistic statement in her use of this beautiful combination of blue and white set off by the red and white stripes of the flag.”

Patrick Bell: Well, we’ve been in business since July 4, 1976. We’re based out of New Hope, Pennsylvania, and now also maintain a location by appointment in New York City. And we’ve been dealing American painted furniture and folk art for that entire period of time. And we have been at the Winter Antiques Show now for twenty-two years.

Benjamin Miller: That’s a lot of years.

Patrick Bell: It’s aging me.

Benjamin Miller: And you’re back for more punishment?

Patrick Bell: We are here for the duration.

Benjamin Miller: And one thing that you’ve brought with you this time around is a quilt. Tell me about this quilt.

Patrick Bell: We have really quite an extraordinary quilt with us this year, both historically and graphically. It’s called the Union Star Quilt, it has been published in a couple of books on various topics of American folk art, but a number of things make this quilt special. First of all, it’s not a pattern quilt, meaning it’s not a log cabin or flying geese, or a quilt that you see in multiple examples. This is an individual effort and individual design, and we also know who it was done by and when it was executed because the quilt consists of thirty-nine stars on a blue background. The stars are in white, it’s bordered by white oak leaves and little red leaves and red flowers, and in the center, lower left, is a dove raising a deconstructed American flag with red and white stripes and a single star. And then she has cut out letters that read “ABRAHAM/ LINCOLN/ GRANT PR/” (for “president”), “COLFAX VI” (for “vice president,”) and “THE UNION/ FOREVER 1869” and the Union Star. Then below that it says “THIS QUILT WAS MADE/” in “1869/ BY ELIZABETH HOLMES IN HER 68TH YEAR.” Elizabeth Holmes was a Quaker lady living in Loudoun County, Virginia. So, she would have been below the Mason-Dixon line and in a part of the country that would have been torn apart by the Civil War. She is expressing herself in the only way she was able to, politically. The election of 1868 saw Grant and Colfax come into the White House and she’s first of all giving credit to Abraham Lincoln, then Grant and Colfax as president and vice president, at a time when there still would have been a lot of division and hard feelings about the Civil War, obviously.

Benjamin Miller: So, what would her motivation have been? Was this really a political poster or the equivalent of what we would call a political poster?

Patrick Bell: One can’t help but think that she was making a political statement. It’s just too bold and too obvious. So, she is definitely making a statement about that but I think even more so than the political angle she’s making a statement about America and the fact that the Union stayed together, because she says twice . . . “the Union Star” and “the Union forever,” and I think that really is her statement. She’s also making an artistic statement in her use of this beautiful combination of blue and white set off by the red and white stripes of the flag. It’s really quite a magnificent piece.

Benjamin Miller: Now I think of a quilt as being a private object—you use it in your bedroom—but it’s making quite a public statement in this case. Is that a common occurrence or is that unusual?

Patrick Bell: Generally, I believe quilts that were unique and really showed off the skill of the maker were used as adornments where there was company or guests in the house and, as I understand it, they were often used in guestrooms and laid out just for observation and appreciation, and not for daily use. I have no doubt that this quilt was not used on a daily basis. It would never have survived like this. And so the pièce de résistance of this quilt is in the very lower right hand corner where it says “BY ELIZABETH HOLMES IN HER 68TH YEAR,” that’s followed by a pair of hands that are done in stuffed work, which means that the hands were cut out of white cotton and they were sewn down then left open at one end and stuffed with cotton. And, so, they are dimensional, there’s a three-dimensional affect. As is the dove, the dove is stuffed, as well. So, that is another technique that is found in this piece.

Benjamin Miller: Those really do pop out from the quilt. Well, it’s a very impressive object. Thanks for telling me about it.

Patrick Bell: Thank you for your interest.

Aronson Antiquairs’s bottle vases

Pair of blue and manganese bottle vases by Delft Potteries, c. 1680.

“The trade lines to Europe dried up and the Dutch potters who were making ceramics until that time started to imitate the Chinese porcelain. But it wasn’t porcelain at all, it was earthenware: Delftware.”

Benjamin Miller: Let’s travel back in time . . . from 1869 to 1680. And back to the old country. This is Robert Aronson, the fifth-generation owner of the Amsterdam firm Aronson Antiques. They specialize in Dutch Delftware, that is, ceramics produced in Dutch city of Delft. This city was the home of Vermeer, the origin of delftware, and, well, what else do you need to know? I asked Robert about a pair of vases.

Robert Aronson: They are a pair of pear-shaped vases. They were produced toward the end of the seventeenth century, around 1680, and where until that time most of the objects that we we’re looking at were simply blue and white, this has an added color of purple, a manganese color. And we see on the vases a group of Chinese figures seated under a tree. The tree is blooming, and the entire decoration is within beautiful bands that enclose the entire decoration. Now, Chinese figures on Dutch Delftware—we see that more often because the Dutch East India traders were bringing in Chinese porcelain from around sixteen hundred and it was very much in fashion not only in the Netherlands but all over Europe, and it was traded through the Netherlands through the ships that came in to Holland and from there it was spread over Europe. In the middle of the seventeenth century—so, around 1650—there were civil unrests in China: the end of the Ming era, beginning of the Qing era. And at that time the area where they were producing porcelain got part of the unrest, of the civil unrest, and part of it was burned down. So, the production level, the amount of pieces that they could produce went down significantly and the emperor said, “You know what? Let’s only produce for our home market and let’s not produce any more for export. So, the trade lines to Europe dried up and the Dutch potters who were making ceramics until that time—on a much simpler scale—started to imitate the Chinese porcelain, and this is where—

Benjamin Miller: Oh, right! Out of necessity.

Robert Aronson: Yes, exactly. So, there was a demand in the market and they were supplying the demand with items that very much look like Chinese porcelain but it wasn’t in fact . . . it wasn’t porcelain at all, it was earthenware.

Benjamin Miller: And what’s the significance of the added third color? Was that technically difficult to achieve?

Robert Aronson: That was very difficult and it was produced by a gentleman called van Eenhoorn. Samuel van Eenhoorn was a factory owner. He introduced the third color, so he did quite a lot for ceramics and for the production of ceramics. He also meant a lot for the city of Delft, so, actually, this pair of vases produced at the Greek A factory around 1680 were produced by a very important man who played an important role for both the ceramics and the city. Just to explain a little bit more of why he was so important for the city is that the King of England at that time saw how Delft was expanding and what the quality was of the products that came from Delft. He put out an embargo on anything painted from the Netherlands, meaning the Dutch Delftware.

Benjamin Miller: Really! This was Charles II?

Robert Aronson: Yeah, I think you’re right, I think that was Charles II. And he said, “Well, you’re not allowed to bring in any earthenware anymore from the Netherlands. We want to protect our own market.” Samuel van Eenhoorn together with two other people from Delft traveled to the King of England the year before he died, in 1685, and asked the King of England to lift the embargo. The embargo wasn’t officially lifted, but a year later the Greek A factory was selling quite a lot of pieces to England, so—

Benjamin Miller: I seeee.

Robert Aronson: He did a good job.

Benjamin Miller: Well a little mercantilism goes a long way, doesn’t it?

Robert Aronson: Absolutely. Really. And the blood of the Dutch.

Benjamin Miller: Well, Robert, thanks so much for talking to me!

Robert Aronson: Ben, it’s my pleasure.

Peter Eaton Antiques’s desk-and-bookcase

Desk-and-bookcase, maker unknown, c. 1815–1820. Mahogany and pine. Photography by Rob Day/Zeno Design.

“The house it was built for burned to the ground. Fortunately, this piece had been taken out just a couple of years ahead of that.”

Benjamin Miller: Now we’re going to go from a Chinese-inspired Dutch piece to an English-inspired American piece. Next up is Peter Eaton, of the creatively named firm Peter Eaton Antiques. Peter and I talked about a real monster of an object, a secretary bookcase.

Benjamin Miller: And its quite a tall piece. What is this, eight feet?

Peter Eaton: It’s exactly eight feet tall to the top of the finial, and exactly six feet wide at its widest. One drawer pulls out and is a desk and the two big doors are for file cabinets and then the entire top section is glazed for ledgers or books.

Benjamin Miller: And the doors in the upper section have a kind of a gothic arch shape to them.

Peter Eaton: Right, right. Some of the interesting points about this are what remains of its history. I have photos of the house that it was made for and then pictures of the house with the secretary in place. The house was built between 1804 and 1808 in a small town called New Braintree, Mass., which is just south of Worchester. And the house stayed in the Penniman family until 1917 when it burned to the ground. Fortunately, this piece and some of the other pieces of furniture had been taken out just a couple of years ahead of that.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, wow, a close shave.

Peter Eaton: It was a close shave. Then it stayed in the Penniman family until 1913, when it was sold to a collector from North Andover, Mass., a man named George Stevens. He was the second owner, and the Stevens family kept it for three generations and then donated it to a museum on the North Shore. I purchased it from the museum when they deaccessioned it several years ago.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, I see.

Peter Eaton: But we have the pictures of the house, we have pictures of it in the house, we have the bill of sale from 1913, the history of the house and the history of the Penniman family, all included with it.

Benjamin Miller: How unusual is it to have that level of documentation for an early American piece of furniture?

Peter Eaton: It is very unusual, very unusual, yes. This was made probably about 1815 in Salem, just for the Penniman family. So, it’s nice to know that something was made specifically for someone else and has survived intact that long.

Benjamin Miller: Has is attracted some attention at the show?

Peter Eaton: It has attracted a lot of attention, most positive, although most people say, I wish I had a place to put it, because it is pretty large.

Benjamin Miller: We are in Manhattan, after all.

Peter Eaton: Well, that’s what I thought, and there are a lot of buildings with high ceilings that I thought could perhaps fit it in, so we’ll see.

Benjamin Miller: I’ll see if I can squeeze it into my closet.

Peter Eaton: Excellent idea.

Benjamin Miller: Peter Eaton, thanks very much.

Peter Eaton: Yup, thank you very much.

Benjamin Miller: I have to report that this piece has been sold but you’ll find plenty of other fine pieces in his Newbury, MA shop.

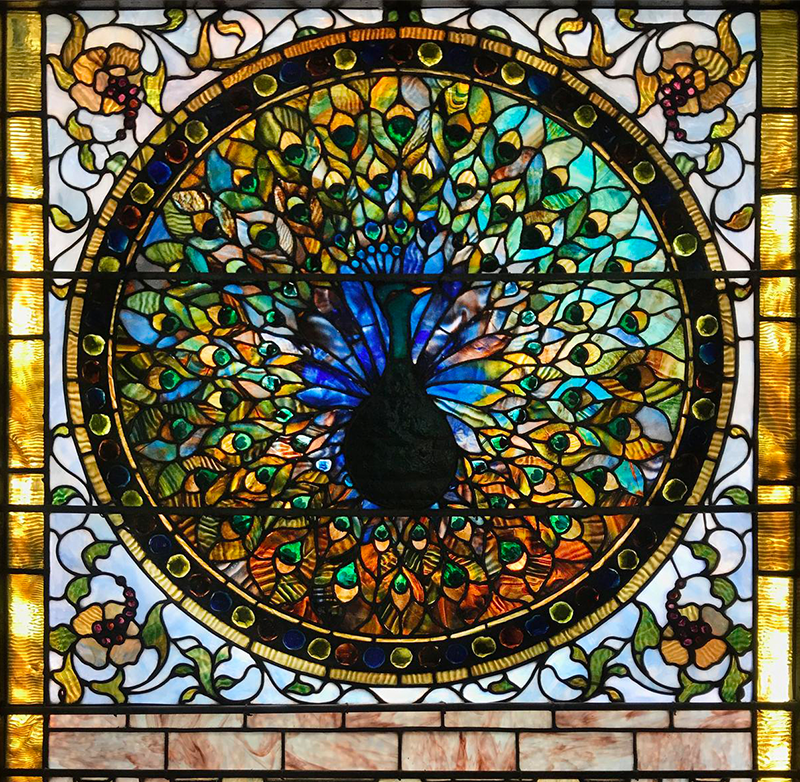

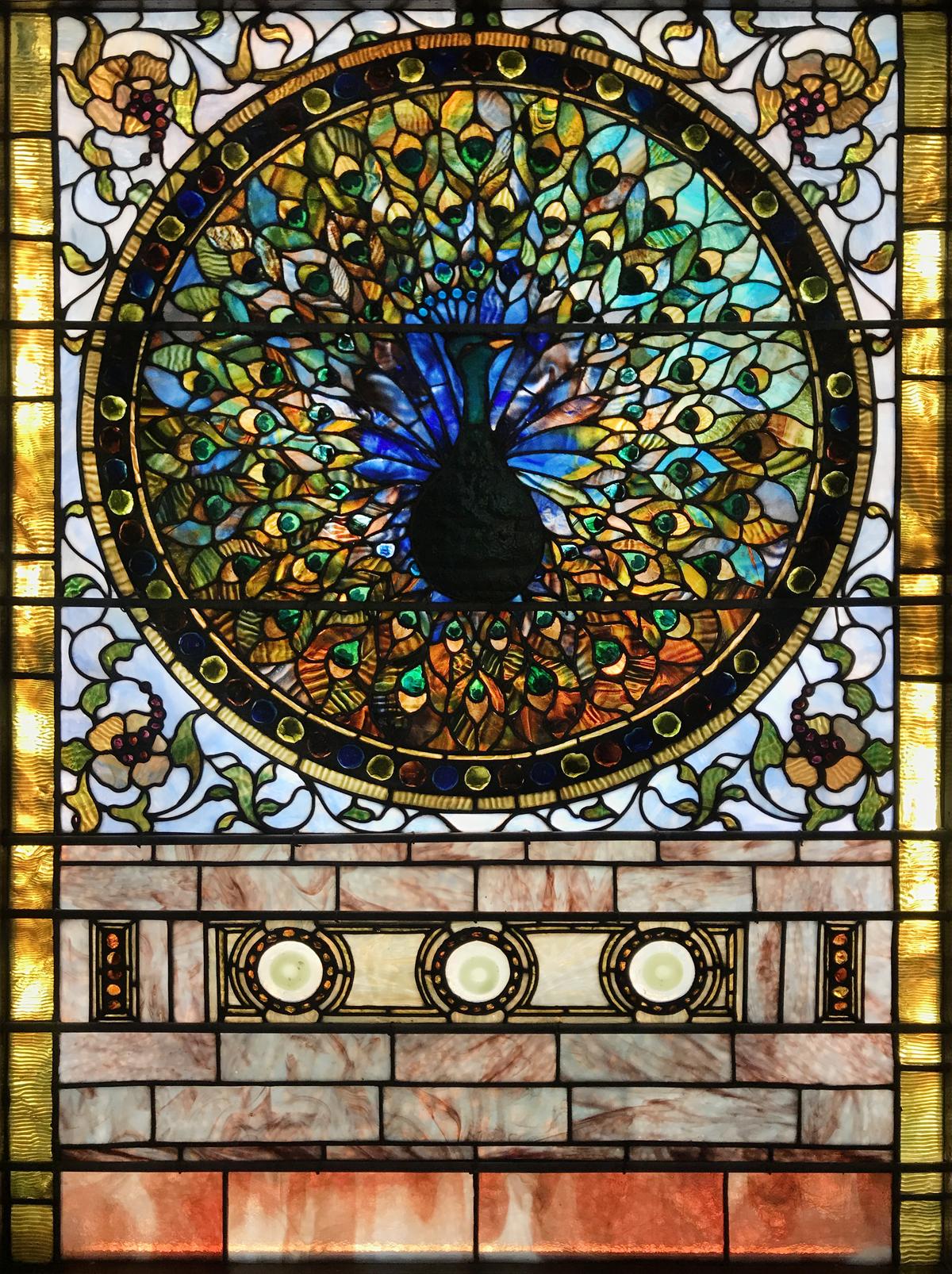

Lillian Nassau’s Tiffany Peacock window

Early Peacock window by Tiffany Glass & Decorating Co., c. 1890–1895. Leaded glass, bronze support rods in wooden frame.

“There are multiple layers of glass and the peacock eyes are green but there’s also a little acid-etched heart of blue.”

Benjamin Miller: We all know the name Tiffany. But they make more than diamond engagement rings. And they used to make some of the finest stained glass in the world. My next guest is Arlie Sulka, of the seventy-year-old New York City firm Lillian Nassau–and also, I should mention, the Antiques Roadshow. I asked her about a flamboyant Tiffany stained glass window.

Arlie Sulka: We’re looking at an early Tiffany window from the 1890s.

Benjamin Miller: And this piece, this window, is about, what, three by five feet, give or take?

Arlie Sulka: I’m gonna say yes, that sounds pretty good . . . by sight.

Benjamin Miller: And it features a peacock . . .

Arlie Sulka: Yes, a peacock medallion. And it is floating over a balcony. And it’s actually very architectural, in spirit . . . no, in design, I should say. And I wanted to say we actually owned this window several years ago and I didn’t know much . . . as much about Tiffany windows back then as I do now. Since we have now gotten this window back I have made some fabulous discoveries.

Benjamin Miller: What have you found out about it?

Arlie Sulka: Well, we never knew how this window was used and we got behind it when it came back into the gallery and discovered that there are two original frames on this window. The interior original frame on one side has three cutouts for hinges and on the other side there’s a cutout for a latch and behind that frame is another frame that has very old weather proofing on it.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, wow. Is there also a Declaration of Independence somewhere in there?

Arlie Sulka: No, no . . . but this is still very good. Another thing that we learned about this beautiful piece is the plumage on this peacock is just absolutely amazing. The glass in it, there is rippled glass, there are multi-layers of glass, and the peacock eyes themselves, they’re green but there’s also a little heart shape of blue. We had thought probably the first time that that was just one piece of glass, but when we examined it from behind . . . we realized that the little heart was acid-etched.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, wow.

Arlie Sulka: So, there was another layer of glass over the green initially, then, with acid etching, they made it into that little heart and that forms the peacock eyes.

Benjamin Miller: Great attention to detail.

Arlie Sulka: Beautiful. It’s a technique that was used all the way through the window making. But this . . . in style alone, one of the reasons we also decided that this was made between 1890 and 1895 is because it has more of an aesthetic nature to it. It’s not super art nouveau, it’s not . . . it’s not like . . . it doesn’t show a peacock it the style that you’ll see in the later windows. Usually that peacock would be perched on a balustrade with this beautiful landscape behind it and with the tail flowing beneath the body of the peacock rather than having the fan of the peacock making up the majority of this roundel.

Benjamin Miller: Well, it’s a beautiful and memorable piece. Thanks so much for telling me about it.

Arlie Sulka: Oh, you’re welcome. I’m always excited to talk about it.

Benjamin Miller: It’s time for another word from our sponsor, America’s oldest auction house, Freeman’s. Located in Center City Philadelphia, Freeman’s has been telling the story of valued objects and collections since 1805. Today, Freeman’s believes in a unique standard of one-on-one service, and their tradition of excellence has benefitted generations of private collectors, institutions, advisors, estates, and museums. Freeman’s holds more than two dozen auctions a year, across all collecting categories, from American Furniture and Decorative Arts to Modern & Contemporary Art. With international experience and comprehensive knowledge of market conditions, the specialists at Freeman’s work closely with consignors and collectors to offer unparalleled assistance in the sale and purchase of fine art, furniture, decorative arts, jewelry, books, and more. All of Freeman’s auctions and catalogues are published online. Their app, Freeman’s Live, is a complimentary service that allows users to bid in real-time from any mobile device or desktop. Freeman’s is currently inviting consignments for their Spring 2018 auction season. For those clients outside the Philadelphia area, Freeman’s regional representatives in the New England, Southeast, and West Coast areas are available to assist you with every step of the consignment process. Let Freeman’s help tell your story; for more information or to set up a complimentary and confidential auction valuation of a single object or an entire collection, please visit Freeman’s online at www.freemansauction.com

Hirschl & Adler’s Valencia Oranges by William McCloskey

Valencia Oranges by William McCloskey, 1889.

Valencia Oranges by William McCloskey, 1889.

“Paintings like these were very attractive to the upper middle–class buyer in late-nineteenth century America. They appealed to people who had nice but modest homes.”

Benjamin Miller: If you’ve listened to Curious Objects before, you may remember my interview with Stuart Feld, president of the New York firm Hirschl and Adler, about a Boston linen press. Well, at the Winter Antiques Show, I got to talk with one of Stuart’s colleagues, Eric Baumgartner. And we spoke about something completely different.

Eric Baumgartner: That’s right, we’re going to be talking about flat art, as opposed to furniture or decorative arts, that I’m sure that Stuart spoke with you about.

Benjamin Miller: And, so, what’s this painting that we’re looking at?

Eric Baumgartner: It’s a work by an artist named William McCloskey, who was an American still life painter active in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Our painting is a painting of Valencia oranges, and what is distinctive about these oranges is that some of them are wrapped in white, waxy tissue. McCloskey in the early 1880’s lived in Los Angeles, right around the time that the citrus industry was beginning to take off. Part of the reason it was doing so well was because the citrus growers were able to ship their product to the east by railroad, with the oranges being wrapped in this protective tissue.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, right.

Eric Baumgartner: And McCloskey thought it would make a great subject for a still life. He did a series of still life paintings of oranges, lemons—many of them wrapped in this very dry, very tactile tissue. It created, I think, as a body of work, a very abstract type of still life that really is his signature subject.

Benjamin Miller: So, this is really a very commercial subject?

Eric Baumgartner: It is, actually, yes. And McCloskey latched on to it at just the right time because the citrus growers started to ship the product to the east wrapped in this white tissue. But then about ten years later, in the late 1890’s, they discovered that . . . Why not print our advertising on the tissue? So instead of it being just plain white, it might say “Sunkist Growers,” and that would have changed the whole tenor of McCloskey’s abstraction, by having these words or colors or whatever on the white tissue instead of just plain white.

Benjamin Miller: Was he good at self-promotion? Was he popular during his life?

Eric Baumgartner: He actually was relatively popular. He painted our painting and worked in New York City after living in Los Angeles for a few years. And his wife, Alberta McCloskey, was also an artist. They were good self-promoters. Maybe not great self-promoters, but good. And paintings like the oranges painting that we have in our booth are . . . were very attractive to the upper middle–class buyer in late nineteenth century America. They’re not big paintings, generally, though this one is a little larger than most. So, they appealed to people who had more modest . . . nice, but modest, homes. And they were great paintings for a dining room setting or parlor setting. They were sized for that.

Benjamin Miller: I don’t think of late nineteenth century California as being a center of creative arts. Is that a misperception on my part? Were there other artists active?

Eric Baumgartner: Well, there actually were and a few of the others were still life painters, but as time went on, of course, and it became more populated and, I think, wealthier, I think a lot of artists went there for all the reasons that you could imagine today. For the weather, for the great, great light, and, I think, in McCloskey’s case, he went there and discovered that he loved painting citrus fruit.

Benjamin Miller: And, I assume, eating them.

Eric Baumgartner: And probably eating them as well.

Benjamin Miller: Thanks very much, Eric.

Eric Baumgartner: My pleasure.

A La Vieille Russie’s Russian-crown-jewel spray brooch

Pearl and diamond spray brooch made for Empress Elizabeth, maker unidentified, c. 1760.

“You’ve got to remember that Russia is very cold and in the winter time they wore very heavy clothing. So, they needed big jewelry or else you wouldn’t see it.”

Benjamin Miller: There’s an old Russian saying: “It’s not gods who make pots.” But maybe it could be gods who make diamonds. Next I’m speaking with Peter Shaffer of A La Vieille Russie—wait, let me try that with the proper accent: A La Vieille Russie. My apologies. Anyway, I asked Peter about a very special piece of diamond jewelry. You guys deal in jewelry and this is not just any jewel—it has a hell of a provenance.

Peter Schaffer: It’s not any jewelry at all. It’s one of two that we know of from the Russian crown jewels. There is a slightly larger version that is still in Russia.

Benjamin Miller: So, give me a little bit of context here. When was it made and for which of the—

Peter Schaffer: It’s late eighteenth century so it would be the period of Catherine the Great. Most of the jewelry from the Russian crown jewels were made for Elizabeth, which was before Catherine.

Benjamin Miller: How many of the Russian crown jewels are in private hands now?

Peter Schaffer: Now you’re asking me a question that I don’t think I can answer. But quite a lot because in 1923, I think it was, they sold a whole bunch of them and . . . uh, no, I think it was 1926.

Benjamin Miller: Either way.

Peter Schaffer: Either way, either way. And they sold some things and also—can’t remember his first name—Kunz, who was the stone man for Tiffany—

Benjamin Miller: A quick note for listeners—Peter is talking about George Frederick Kunz, the great gemologist who traveled the world seeking out gemstones for Tiffany.

Peter Schaffer: —I think it’s in the archives in Washington . . . they have some things that he acquired at the time of the crown jewels which didn’t make it into the official book, but that they are official pieces.

Benjamin Miller: So, this piece is predominantly diamonds and it also has pearls and it’s in the form of leaves with the pearls serving as fruits dangling from the branches. Is that right?

Peter Schaffer: That’s a good . . . as good a description as anything. I think it’s a floral spray, and this type of thing might have been originally worn as a hair ornament.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, I see. And it’s very large. It’s three or four inches high.

Peter Schaffer: Yeah, yeah.

Benjamin Miller: And it has a lot of diamonds in it.

Peter Schaffer: Yeah, it has a lot of diamonds in it. No, you’ve got to remember that Russia is very cold and in the winter time they wore very heavy clothing. So, they needed big jewelry because if they wore what a lot of people wear in this country, you wouldn’t see it.

Benjamin Miller: I see. So, this was merely a practical ornament.

Peter Schaffer: Yeah, purely practical. Big diamonds.

Benjamin Miller: Wow. And, so, was this actually worn and was it used by the royals or . . . ?

Peter Schaffer: We don’t know. We believe so.

Benjamin Miller: It’s an amazing piece to look at. Thanks so much for talking to me, Peter.

Peter Schaffer: Thank you.

Spencer Marks’s Japanese Work Gorham tea set

Gorham Japanese Work tea set chased by Subero Yamamoto, 1906.

“There is a mistaken thinking amongst American decorative arts people that after the Japan craze in the 1870s Japan went out of style.”

Benjamin Miller: I hope you’re having as much fun as I am. We have three more to go for today’s episode. My next guest is, like me, a silver dealer, and while I’ve known the firm for years, this is their first time exhibiting at the Winter Antiques Show. They brought an all-star cast for their debut. I’m here with Spencer Gordon. And you’re in business with . . . ?

Spencer Gordon: Mark McHugh.

Benjamin Miller: And your company is named . . . ?

Spencer Gordon: Spencer Marks.

Benjamin Miller: I don’t know how I’m possibly going to remember that.

Spencer Gordon: (Laughter)

Benjamin Miller: And what are we looking at today?

Spencer Gordon: Well, I was going to show you what Gorham called a Japanese Work tea set. There is a mistaken thinking amongst American decorative arts people that after the Japan craze in the 1870s Japan went out of style. The truth is that people continued to be interested in Japan and Japanese arts and Gorham did Japanese work silver—what they called Japanese Work silver—in the 1890s and in the early 1900s.

Benjamin Miller: So, this piece is a . . . it looks to be a six-piece tea set on a tray, all made in silver, with ivory insulators, gilt interiors. And it’s decorated very elaborately with chasing—sorry, I’m a silver dealer, too—

Spencer Gordon: (Laughter)

Benjamin Miller: So, I hope we’re not alienating our audience here but I like to geek out a little bit over this stuff. But tell me, When did Gorham make this? And they were based in Providence, right?

Spencer Gordon: Right, right. The remarkable thing about this is that Gorham hired a Japanese chaser to come to Providence and make a very, very special and rare line of silver they call Japanese work. And this was chased by—and his American name is Subero Yamamoto, and Americans always mess up foreigners’ names—

Benjamin Miller: I’m not even going to try that.

Spencer Gordon: —so that’s close to his Japanese name. But he spent about 850 hours doing the decoration on this—

Benjamin Miller: Whew!

Spencer Gordon: —on this tea and coffee service. That’s roughly three months of the time he spent at Gorham (he was there for three years). It’s the most important and impressive thing that he was involved in making.

Benjamin Miller: Wow.

Spencer Gordon: It is encrusted with chrysanthemums in high relief and then there are these lovely low-relief leaves in the background, and that goes all over the tray and the teapot, the coffee pot, kettle, etc. The bodies were all hand-raised before he did his chasing. It had a retail cost of $1800 or $1900 in 1906 when it was made, and back then that would have bought you four or five cars.

Benjamin Miller: Wow!

Spencer Gordon: Yeah, it’s a ton of money.

Benjamin Miller: So, each one of these pieces is a Model T, more or less.

Spencer Gordon: More or less, yeah (laughter). Although they came in more than just black.

Benjamin Miller: Well, any color as long as it’s silver!

Spencer Gordon: (Laughter)

Kentshire Galleries’s Ernesto Pierret serpent bracelet

“It’s the verisimilitude to an actual snake that makes it so dynamic . . . as opposed to coiling a snake around your wrist and saying ‘Look, this is in the ancient taste.’”

“It’s the verisimilitude to an actual snake that makes it so dynamic . . . as opposed to coiling a snake around your wrist and saying ‘Look, this is in the ancient taste.’”

Matthew Imberman: I’m Matthew Imberman, I’m co-owner of Kentshire along with my sister, Carrie Imberman. And we’re the third generation of the family to run the business and we deal in antique and estate jewelry.

Benjamin Miller: Ok, I was going to let Matthew go ahead without an introduction, but, do you remember your Shakespeare? All that glisters is not gold? I’m sure that’s very wise, but…well, this next piece is. Gold. Ok, sorry. Back to Matthew from Kentshire.

Benjamin Miller: And you’re located . . .

Matthew Imberman: We’re located in Bergdorf Goodman on the seventh floor next to the restaurant, and then we have private offices in Rockefeller Center.

Benjamin Miller: Today we’re talking about a bracelet by Pierret.

Matthew Imberman: It’s by Ernesto Pierret. It dates to the last quarter of the nineteenth century before his son Luigi took over, we think. It’s a really interesting sculptural snake bracelet, and obviously the nineteenth century has a lot of different snake bracelets and this one is entirely gold granulation and then has a lovely large diamond set into the head. But it’s constructed in such a way . . . it’s almost like it’s two pieces that are fit together and coil around each other so it seems almost perfectly seamless. And it’s really kind of a marvel of construction from the time period, at least in our opinion. We’ve owned a lot of lovely, you know, antique, you know, archaeological revival pieces. For us this is just a step above most things we see.

Benjamin Miller: And before we started you were drawing a comparison between Pierret and Castellani, who is a jeweler maybe more people are familiar with.

Matthew Imberman: Yeah, so, Castellani, obviously, you know . . . that’s one of the, let’s say, “blue chip names” from, you know, late nineteenth century jewelry. Pierret was a native Frenchmen but moved to Rome and at some point apprenticed with Castellani or worked in his shop—some people say maybe actually taught Castellani. There’s a little bit of back and forth about the relationship, but we do know that he was working within the studio then went off onto his own and ended up marrying the daughter of a papal lawyer, if my memory serves me correctly. So, [he] kind of came into money or “married up,” let’s say, to the point where he was able to start producing on his own, have his own studios, and live in quite a nice area. So, when I look at Castellani jewelry, which is obviously such beautiful, let’s say, reinterpretations of what you might find in some of the archaeological digs that were being done in that time and this just general kind of Grand Tour fascination with making things in the antique taste as accurately as you could, Pierret, to my eye, tends to look a little bit more as if he was trying to imagine what somebody would have made for people at the time but that hadn’t just been dug up. It’s really pared down, it’s not overworked, it’s not overwrought with ornament, and this bracelet to me is that. It’s striking in that it’s the coil of the serpent, the angle of it, and the verisimilitude to an actual snake that makes it so dynamic . . . as opposed to coiling a snake around your wrist and saying “look, this is in the ancient taste.”

Benjamin Miller: It strikes me as maybe a little bit more wearable than some Castellani pieces.

Matthew Imberman: Yes, very much so. And, I mean, it’s an academic piece if you want it to be, only because Ernesto Pierret didn’t have huge output, the pieces tend to be, for collectors, you know, a prized possession. They are rarer. But, also, I do . . . just having seen people try this on a number of times—it sits beautifully on the wrist, and it’s real jewelry meant to be worn.

Benjamin Miller: Have people been looking at it at the show?

Matthew Imberman: Yeah, they have! We’ve been fortunate to have a few people who’ve been intrepid enough to try it on. I think people sometimes shy away from trying on pieces, especially antique ones. Obviously, there is . . . they are old and they’re worried about the condition. This one is crafted so beautifully that it goes on and off very well. And that’s a sign of good jewelry in general, as you know: if it’s meant to be worn it shouldn’t be so difficult to put on.

Benjamin Miller: Absolutely. Well, that’s great to hear. Thanks for joining me.

Matthew Imberman: Thanks for coming by.

Kelly Kinzle Antiques’s inlaid sideboard

Inlaid sideboard by Harrison Webber, c. 1900.

“There are 150 thousand individual pieces inlaid into the entire piece. . . . in a comparison of the execution, the detail, everything, this is a stand-alone object.”

Benjamin Miller: One more to go today. And—although it’s dangerous for me to say it—this is maybe the most visually striking of them all. It’s not the oldest or flashiest or even the most valuable piece we’ve looked at, but the sheer intricacy of craftsmanship is hard to compare. I’m with Kelly Kinzle. You’re up from Pennsylvania and you’ve brought with you a very interesting piece of furniture, which, I have to say is . . . visually, it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen before because of the incredible amount of inlay. So, tell me a little bit about this piece and where it comes from.

Kelly Kinzle: Well, this piece was made in Reading, Pennsylvania and it was made by a man named Harrison Webber. He spent twelve years making this inlaid sideboard and—

Benjamin Miller: Twelve years?

Kelly Kinzle: Twelve years and he estimates there are 150 thousand individual pieces inlaid into the entire piece.

Benjamin Miller: Holy cow.

Kelly Kinzle: It has four American flags on it and when he completed it, right around the period of 1900—he started in 1890 and he completed it just about . . . probably, really, if you read his paperwork, 1902—he then took it to the St. Louis Exposition and tried to sell it for $6,000.

Benjamin Miller: That doesn’t sound like a lot of payoff for twelve years work.

Kelly Kinzle: No, but in 1904, $6,000 was a tremendous amount of money.

Benjamin Miller: And did he get $6,000?

Kelly Kinzle: No, it remained in his family until the 1990s.

Benjamin Miller: Oh, my gosh.

Kelly Kinzle: And he sold it . . . the family sold it and a collector in Allentown bought it and it remained in his collection until I bought it about six months ago and it’s an ideal piece for this New York show.

Benjamin Miller: So, give me some context here, is there anything like this in the world?

Kelly Kinzle: There are no comparables to this piece. There are other pieces of folk art inlaid furniture that have sold, that people collect—tramp art and other lower . . . lower quality things—but in a comparison of the execution, the detail, everything, this is a stand-alone object.

Benjamin Miller: So, this brings new meaning to the idea of a singular work of art.

Kelly Kinzle: Yes, yes. And a piece that is just so . . . the cabinetmakers that came through and looked at this piece were absolutely amazed at the execution and could not imagine how some of it was even done.

Benjamin Miller: Well, I have to encourage listeners to look at the picture of this online because its really hard to describe how intricate it is. But it’s an incredibly impressive piece of craftsmanship. Thanks so much for talking to me about it.

Kelly Kinzle: Sure, thank you!

Benjamin Miller: And that wraps up today’s tour. I want to say a huge thank you to all the experts who took the time to talk with me. I hope you’ll take a minute to look them up, because the objects you’ve heard about are just the tip of the iceberg as far as what they have to offer. Next episode I’ll have even more conversations with dealers from the Winter Antiques Show—including, frighteningly for me, one with my own employer—so I hope you’ll come back for that one. As always, look for pictures of all these objects at themagazineantiques.com/podcast. Today’s episode was produced and edited by Sammy Dalati. Our music is by Trap Rabbit. And I’m your host, Ben Miller. Thanks for listening.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com.