This time it’s your turn. For the last two months, we’ve asked listeners to post their curious objects on Instagram, tagging #mycuriousobject and @antiquesmag. You can see the results of that campaign by searching the hashtag on Instagram: more than seventy superb items from galleries, museums, and private collectors, including a scale model of a Wankel engine, a weathervane shaped like a 1909 Hupmobile (do its age and patina make it a jalopy?), and a man’s shirt collar scribbled with a message from a survivor of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. We had the unenviable task of deciding on just a handful to feature on this month’s episode of Curious Objects, but we finally decided on:

This time it’s your turn. For the last two months, we’ve asked listeners to post their curious objects on Instagram, tagging #mycuriousobject and @antiquesmag. You can see the results of that campaign by searching the hashtag on Instagram: more than seventy superb items from galleries, museums, and private collectors, including a scale model of a Wankel engine, a weathervane shaped like a 1909 Hupmobile (do its age and patina make it a jalopy?), and a man’s shirt collar scribbled with a message from a survivor of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. We had the unenviable task of deciding on just a handful to feature on this month’s episode of Curious Objects, but we finally decided on:

@jeremy.k.simien’s portrait miniature of a free Creole man

@museumofcityny’s transfer-printed teacup

@michaeldiazgriffith’s folk watercolor attributed to I. F. Zeidler

@thejewishmuseum owl-shaped spice container

@curatereynolda’s antique aviators goggles

@californiahistoricalsociety’s letter from the San Francisco earthquake of 1906

@americanantiquarian’s mummy linen

@sjshrubsole’s silver inkwell with ties to Shakespeare

Listen to the episode using the player below:

Benjamin Miller: Hello and welcome back to Curious Objects & the stories behind them, brought to you by The Magazine ANTIQUES. I’m your host, Ben Miller. Today’s episode is a little different. If you’ve been listening to the show, you’ve heard me logrolling for the #MyCuriousObject Instagram campaign. I’ve been asking you, dear listeners, to post images of your own objects that are fascinating or beautiful or rare or that have great stories behind them. Thank you so much to everyone who participated. If you use Instagram, I hope you’ll take a few minutes to browse through the objects—there’s a wealth of educational and eye-opening and just plain quirky pictures. And if you don’t use Instagram, this might actually be a good reason to start!

Anyway, I had wanted to feature one or two of these objects on the podcast, but, given how many fantastic posts you wonderful people have made, it became clear that I really needed a whole episode if I were even going to begin to do justice to them. So, today’s episode is the#MyCuriousObject episode! You’ll hear about just a handful of the objects that have been posted—and there are so many great ones that we just don’t have time for—but I’m truly impressed by all of the objects you’ve shared, and by the research and knowledge you’ve added to them, and I’m thrilled to be able to include some of you in the podcast.

As always, images of all the objects are available at themagazineantiques.com/podcast, and I also post more Curious Objects images on my Instagram, @objectiveinterest—even some behind-the-scenes stuff, if you’re into that!

Today’s episode is sponsored by Freeman’s America’s oldest auction house, located in Center City, Philadelphia. And we have another sponsor: Reynolda House Museum of American Art, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Jeremy K. Simien’s portrait miniature

Portrait miniature of a free Creole man by an unknown artist, c. 1840s. Watercolor on ivory and brass, 2 1/2 by 2 inches. Collection of Jeremy K. Simien.

“While all images of free people of color are rare, especially rare are these images of free men of color.”

Jeremy Simien: Hello, my name is Jeremy Simien. I’m thirty-three years old, I live in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and I’m a collector of antiques.

Benjamin Miller: We’re going to hop around today to a lot of different times and places, but I want to start with an object from antebellum Louisiana. This was posted by Jeremy Simien. It’s a miniature portrait. If you’ve been listening to Curious Objects for long enough, you might remember my conversation with Wade Lege about his Greek revival home, originally on the banks of the Mississippi River in Louisiana. Wade’s house tells an important story about the wealth and taste of the slaveholding elite; but while Jeremy’s curious object comes from the same era and region, it sheds a very different light on this culture. I’ll let Jeremy give you the story.

Jeremy Simien: This portrait is small but significant. Miniature portraits are, as the name suggests, quite small-scale. This piece measures only about two and a half inches tall and two inches wide. This watercolor on ivory is circa 1840 and depicts a man of African descent who is of medium to dark complexion, with a mustache. The gentleman appears to be about thirty years of age and is finely dressed, with a black jacket, white shirt, and a thinly-tied cravat. I acquired this piece from auction two years ago, and since then I have loaned it to two Louisiana museums for viewing. While the portrait has New Orleans provenance, sadly, the sitter is unidentified. However, when considering the time period, manner of dress, and the appearance of the sitter in the portrait, one can make the assertion that the gentleman is a member of les gens de couleur libres, as they were known, or “the free people of color,” as they are known today. During the antebellum period, New Orleans, Louisiana, had the largest population of free people of color. This group consisted of people of variant degrees of African descent who were either born free, had become free through manumission, through self-purchase, or even through military servitude. Free people of color accounted for one fifth of the population of New Orleans and owned a third of the properties in the French Quarter. Many were skilled artisans, developers, and builders. Others were doctors, lawyers, and even inventors. They did not only survive but thrive, and, in effect, contributed greatly to the culture and economy of Louisiana. And, in fact, their influence can still be found today. While there are many depictions of nineteenth-century African Americans and other people of African descent in the Americas, very few were commissioned and painted for the express benefit of this group. So, while all images of free people of color are rare, especially rare are these images of free men of color. Many of these portraits did not survive Jim Crow–era America as they were seen as a threat and challenge to the once-widely-held belief of white supremacy.

Benjamin Miller: A huge thank-you to Jeremy, who is on Instagram as @jeremy.k.simien, for that story. It’s not hard to argue that the loss and destruction of African-American material culture is the greatest tragedy in American antiques, so it’s a privilege to hear about an antebellum memento like this.

The Museum of the City of New York’s transfer-printed teacup

Teacup depicting temperance advocate Father Theobald Matthew made by William Adams & Sons, c. 1849–1851. Transfer-printed earthenware; height 2 ¼, diameter 4 inches. Museum of the City of New York, gift of the U.S. General Services Administration.

“This cup is one of the only surviving relics of nearly a million objects from the Five Points and African Burial Ground archaeological sites, which were stored in a basement in the World Trade Center and lost on September 11, 2001.”

Benjamin Miller: Let’s stick around in the 1840s for a little longer. But now we’re heading north from the bayou and the delta, over the Mason-Dixon line, to New York City. The Museum of the City of New York—they’re at @museumofcityny on Instagram—posted a curious object that I just have to tell you about. Their curator Steven H. Jaffe sent me some extra information—I just want to share a few excerpts with you. The object is a teacup called the Father Matthew cup, and it was found at no. 472 Pearl Street in lower Manhattan in 1990 or 91. Here’s what Steven wrote, as read by this podcast’s editor, Sammy Dalati:

This is a small earthenware cup decorated with brown transfer-printed images, made by the Staffordshire pottery firm of William Adams & Sons. The principal image on the cup depicts the Irish priest Father Theobald Matthew, pioneer of the Total Abstinence movement which exhorted men and women to “sign the pledge” promising to abandon all alcoholic beverages. Matthew toured the United States in 1849–1851, and the purchase of the cup by a tenant of 472 Pearl Street may well date from the period of this tour.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when this cup was owned and later thrown into a privy, this block of Pearl Street was part of the Five Points neighborhood, infamous among journalists and reformers of the day as a crowded and boisterous district of working-class shanties, early tenement houses, taverns, and brothels. When unearthed, the cup—along with other artifacts—helped archaeologists re-envision the neighborhood’s historic meaning and identity. The moralistic, pro-temperance message of the cup’s imagery flew in the face of inherited stereotypes of the Five Points as a den of vice.

This cup, along with seventeen other artifacts from the excavation are the only surviving relics of nearly a million objects from the Five Points and African Burial Ground archaeological sites that were stored in a basement in the World Trade Center and lost on September 11, 2001. The cup and its accompanying pieces were on loan to the South Street Seaport Museum at the time, thus escaping destruction. Donated by the US General Services Administration to the Museum of the City of New York in 2007, the cup is currently on display in our long-term exhibition, New York at Its Core.

Benjamin Miller: Many thanks to the museum for this object and story. A remarkable thing about studying antiques is how often you find pieces like this whose drama continues long past their original use, even to the present day, and which take on layer upon layer of additional meaning as their lives go on.

We’ll be back with more curious objects after this.

Detail of Teacup depicting temperance advocate Father Theobald Matthew. Museum of the City of New York, gift of the U.S. General Services Administration.

Benjamin Miller: Our first sponsor for this episode is Freeman’s auction house in Center City, Philadelphia. Whether you’re collecting or consigning, you want to deal with an auction house with a sterling reputation. Try Freeman’s! Freeman’s is the oldest auction house in America, dating to 1805. In my day job I deal in silver and jewelry, and we’ve bought dozens of pieces at Freeman’s, ranging in price from a few hundred to tens of thousands of dollars. But it’s not just silver and jewelry—their specialists offer one-on-one service and expertise across all areas. Freeman’s specialists have worked with generations of private collectors, institutions, advisors, estates, and museums. Their spring sale season this year offered fourteen successful auctions, including eight significant private collections and four auction world records. Upcoming fall and winter auctions include an impressive list of subjects: Asian Arts, Fine Jewelry, Books, Maps & Manuscripts, Americana, British & European Furniture and Decorative Arts, as well as 20th century Design, and American Art & Pennsylvania Impressionists. Freeman’s is inviting new consignments right now. Want to find out more? Go to freemansauction.com.

As usual, I want to take a minute to say thank you for listening. As grateful as I am to everyone who posted their curious objects, the whole reason behind this project is you, listening right now. If you enjoy the podcast and want to help us reach more people, the easiest thing to do is to leave a rating and review on the app that you’re using to listen right now. The second easiest thing to do is to suggest Curious Objects to a friend! Maybe this is obvious, but it’s true that the more people we can reach, the more interesting and ambitious subjects I can tackle. I’m also grateful for your feedback, and I’ve been receiving some really great, helpful comments lately. As always, you can email me at podcast@themagazineantiques.com, and you can also find me on Instagram with the handle @objectiveinterest. And, again, photos of all the objects you’re hearing about are posted at themagazineantiques.com/podcast.

Michael Diaz-Griffith’s folk watercolor

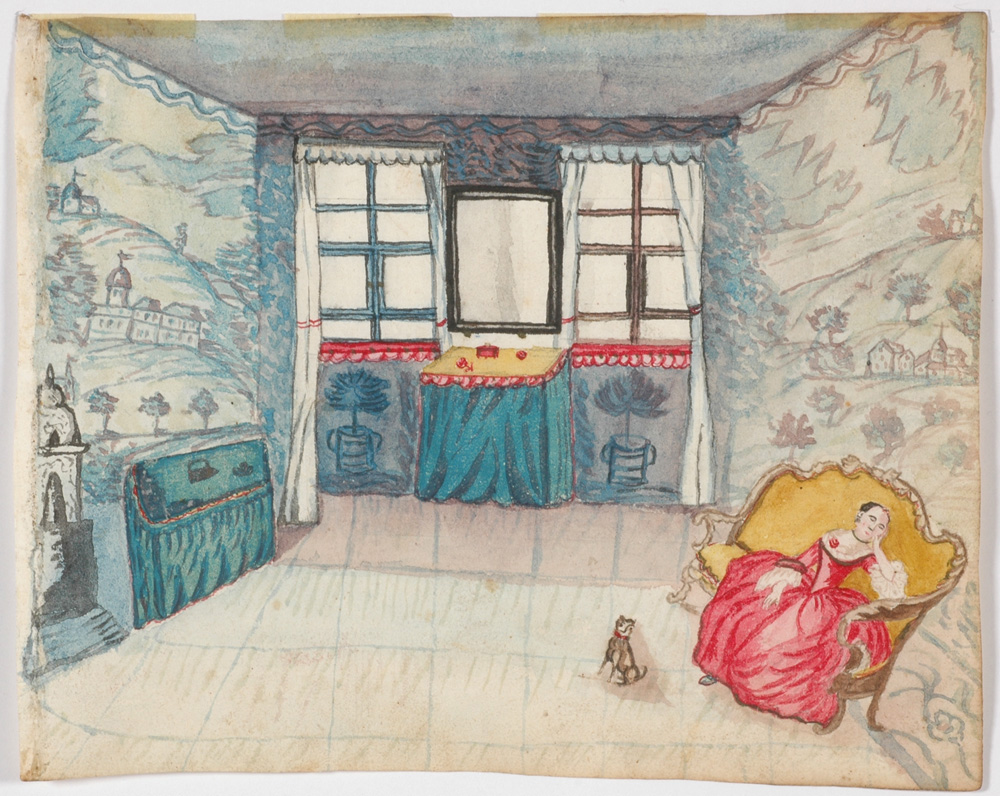

Rococo interior scene attributed to I. F. Zeidler, c. 1750. Watercolor on paper, 5 5/8 by 7 1/8 inches. Collection of Michael Diaz-Griffith.

“There’s reason to believe that this drawing was taken from the album of a young medical student named Christian G. Gross, who collected drawings and paintings at the University of Halle.”

Benjamin Miller: Now we’re going to hear from someone I’ve wanted to have on Curious Objects for a long time. Michael Diaz-Griffith is the associate executive director of the Winter Show. His Instagram handle is @michaeldiazgriffith. He’s a friend of mine and one of the most passionate evangelists for antiques that I know.

Like the teacup from before the break, Michael’s object has layers of meaning—its aesthetic context, its unique features and creativity, but also its history as part of a very curious collection. Here’s Michael with the full story:

Michael Diaz-Griffith: My curious object isn’t quite an object. Or, at least, many might not see it as such. It’s a watercolor drawing of an interior from mid-eighteenth-century Germany. I have reason to believe it was produced in Halle in the early 1750s by an artist named I. F. Zeidler, but I’ll return to that later. What I find compelling about the drawing is that it depicts a high-style interior with grisaille murals and a rococo settee, but it does so in a rather flat, folky manner that I find totally convincing and utterly charming. Watercolor interiors or interior portraits typically depict the contents of a room—their material culture—and I love them for that reason. But this one sort of ups the ante by also depicting a woman dressed in a high-style gown [who’s] engaged in romantic contemplation or fantasy, whiling away the day wistfully on that settee, with her faithful pup nearby. And the human dimension that she gives to the room gives it something special that made it rather irresistible to me as an object to acquire. So, both curious and—how shall I say?—tempting. And I’m also fascinated by the fact that another object stands behind this one. So, there’s reason to believe that—beyond being produced in the early 1750s in Halle by Zeidler—that this drawing was taken from the album of a young medical student named Christian G. Gross, who attended the University of Halle in the same period. And while not much is known about Christian Gross, we do know that he was a medical student who collected drawings and paintings and kept them in this album. I find that fascinating, partly because it speaks to a culture of collecting that’s different from our own—it’s fun to imagine the interests of this young student who had this work in his possession—but also because the object that hangs on my wall is connected to this family of objects that are spread all across the world. I know others who have encountered works from Gross’s album, and while it’s rather tragic that they’re separated, and that the example of material culture that they were collected in is no longer intact, it’s a kind of a fun puzzle to speak to others who have pages or works from that album and to sort of think about the culture of collecting that stemmed from that album. Everything about this work makes me feel curious, and that’s really the reason that I collect: to be stoked on to further questioning and thinking about objects.

The Jewish Museum’s spice container

Spice container by Firm of Neresheimer, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Repoussé, chased, and cast silver, glass, and coconut shell; height 10 ¾, width 4 1/8, depth 5 1/4 inches. The Jewish Museum, New York, The Rose and Benjamin Mintz Collection.

“The head, wings, feet, and base are made of silver, while the body is a coconut shell.”

Benjamin Miller: It’s odd to think about today, but antiques collecting isn’t all that old of a hobby. Of course, there have always been treasured and valued objects—and art enthusiasts like this Christian Gross that Michael just told us about—but the idea of scholarly study and accumulation of compelling pieces was not exactly mainstream until the Rockefellers, Morgans, and others started assembling their great collections in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Not coincidentally, around this time there was also a proliferation of reproductions and pastiches. Which makes this next object very interesting. This was posted by the Jewish Museum here in New York—that’s @thejewishmuseum. It’s a spice container from the early 1900s but made in a sixteenth century style. Now, if the Renaissance period makes you think of dismal paintings of tortured martyrs, don’t worry—this spice container takes on a downright adorable form. Here’s some of what the researchers at the museum told me about the piece, as read by Katherine Lanza:

Out of hundreds of objects on display in the Taxonomies gallery within the Jewish Museum’s exhibition Scenes from the Collection, one of the most curious might be this ceremonial spice container—made from a coconut in the shape of an owl. The head, wings, feet, and base are made of silver, while the body is the coconut shell. This work, created in Hanau, Germany, in the early twentieth century during a craze for older historical objects, imitates sixteenth century silver cups with bodies made of a nautilus shell or ostrich egg. Such objects were a staple of the collections of curiosities belonging to Renaissance nobility.

The spice container is used in a ritual conducted at the end of the Jewish Sabbath. The container holds aromatic spices like cloves or cinnamon, and all present smell the fragrance meant to bring the sweetness of the Sabbath into the rest of the week. The head of the owl can be removed in order to put the spices in the coconut shell and in order to smell the spices during the ritual.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art’s aviators goggles

Aviator goggles in original case, both by American Optical Company, c. 1931–1932. Case: aluminum, 4 by 9 inches. Goggles: metal frame, glass lenses, rubber eyepiece with elastic headband, 2 ½ by 8 inches. Reynolda Estate Archives, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

“Zachary Smith Reynolds wore these goggles during his greatest achievement in the air: a seventeen-thousand-mile solo journey from London to Hong Kong.”

Benjamin Miller: Our next curious object comes from an organization that I know you’re familiar with—it’s one of our beloved advertisers, Reynolda House. They’re on Instagram as @curatereynolda. Now, you’ll have to take my word for it that there was no nepotism involved here . . . actually, when you hear the story, I think you’ll understand why I had to include this one. Take it away!

Bari Helms: I’m Bari Helms, the Director of Archives and Library at Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. In our archives here we have a pair of aviator’s goggles that belonged to Zachary Smith Reynolds. Smith Reynolds was the youngest child of R. J. and Catherine Reynolds (R. J. being the founder of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company). These goggles are an early style of aviation goggles that have a metal frame with clear glass lenses. The have separate rubber eye cushion around the lenses that would help protect the pilot’s face from the frame, and would have been worn with an elastic headband. They come in an aluminum case that identifies them as aviator goggles made by the American Optical Company.

Smith Reynolds made a mark on early aviation. Aviation really captured the imaginations of the Reynolds children. Three of the four learned to fly, including the older sister, Mary. But it was Smith’s older brother Dick Reynolds that first took a business interest in aviation. He founded Reynolds Aviation, and in the summer of 1927, Smith was hanging out with his brother, working on the airfields in Long Island. He rubbed elbows with Charles Lindbergh, and by November of that year, kind of like a teenager asking for his first car, a sixteen-year-old Smith was writing his guardian and uncle Will Reynolds to use some of his funds to purchase his own plane. He earned his private pilot’s license, signed by Orville Wright, at the age of sixteen, and then by age seventeen he actually became the youngest licensed transport pilot in the country. When he was twenty, he married Broadway star Libby Holman who was twenty-eight at the time.

So, Smith had a lot going on before he even turned twenty-one, and by far his greatest achievement in the air was his seventeen-thousand-mile solo journey from London to Hong Kong. In the spring of 1931 he purchased an amphibian biplane, a Savoia-Marchetti S. 56C. It was customized for him to have a single seat with extra fuel capacity, and after several false starts Smith finally began his flight in London in December 1931, landing outside of Paris. He then flew south over Italy and the Mediterranean until he reached North Africa. From there he followed airline routes already established by British fliers, traveling across the Syrian desert from Gaza to Baghdad and on to India.

Smith wore this particular pair of aviator’s goggles during this flight. It would have been an open-cockpit plane, so these goggles really protected his eyes from the sandstorms, the cold, and they helped protect him from the sunlight.

Zachary Smith Reynolds (1911–1932) in a photograph of c. 1928. Reynolda Estate Archives, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

Smith’s accomplishments in the air were really overshadowed by his death that happened a few months later. On July 5 they hosted a birthday party for a friend on Reynolda’s grounds and reportedly Smith and Libby argued that night. Shortly after midnight, a shot was heard from the sleeping porch off the master bedroom. Smith died at the hospital in the early hours of July 6. The death was actually initially ruled as a suicide, but a coroner’s inquisition held a few days later at the house resulted in Libby and Ab Walker being indicted for murder. The sensational nature of the news coverage . . . it really captured the attention of the media and the public, happening so close to the Charles Lindbergh baby kidnapping, [and] the Reynolds family did not like the media pressure and attention and they requested that all charges be dropped, and their request was granted. And, so, the case—whether murder, suicide, or accidental death—still remains unsolved . . .

Benjamin Miller: Speaking of Reynolda, our second sponsor for this episode is Reynolda House Museum of American Art, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Reynolda House is more than just an elegant 1917 historic estate. It’s also home to a compelling and surprisingly wide-ranging collection of fine and decorative arts. Now, if you listen to this podcast, you probably already like house museums. But Reynolda House goes beyond the typical displays of period furniture and old portraits. When you visit, you’ll find thought-provoking objects like American artist Martin Johnson Heade’s most famous orchid and hummingbird painting, tobacco baron R. J. Reynolds’s mink coat, and century-old farm buildings now serving crepes and rose. For any other museums out there listening, let me just say that this is a great idea. They also have a brand-new app you can download called Reynolda Revealed, which takes you on a virtual tour of the museum and grounds. I downloaded that myself and had a lot of fun with it—I highly recommend checking it out at reynolda.org, and of course planning your visit to the house in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. That’s r-e-y-n-o-l-d-a.org.

The California Historical Society’s Frisco earthquake letter

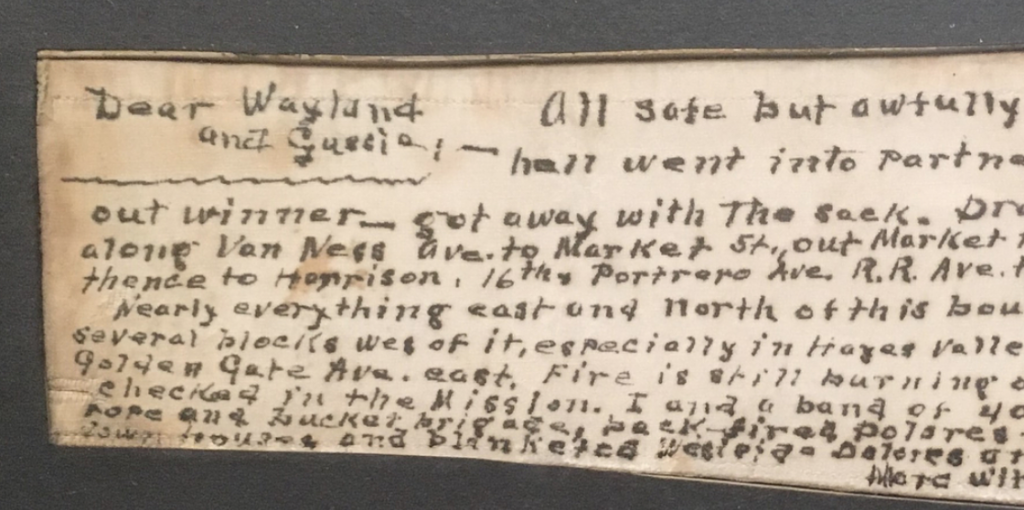

Men’s shirt collar inscribed with letter from James Graves Jones to Mr. and Mrs. Wayland Edgar Jones, 1906. Ink on linen; height 2 3/8, width 8 3/8, depth 1/8 inches. California Historical Society, gift of Alma Jones-Demski and Beverley Jones Bell on behalf of the Wayland E. and Augusta Jones family.

“Draw a line from Ft Mason along Van Ness Ave. to Market St., out Market to Dolores to Twentieth, thence to Harrison, 16th & Potrero Ave., R.R. Ave. to Channel St. and bay. Nearly everything east and north of this boundary line gone.”

Benjamin Miller: I want to mention briefly one especially touching object that was posted by the California Historical Society, conveniently on Instagram as @californiahistoricalsociety. This is a letter, but just as interesting as what’s written in it, is what it’s written on. Specifically, a shirt collar. This letter dates from April 21, 1906, just three days after the terrible earthquake and subsequent fires wrecked the city of San Francisco. Now, many of us know the frustration and anxiety of trying to get a text or cell phone call to go through during a major event—but in the aftermath of this earthquake, the bottleneck was the paper supply. So, when James Graves Jones needed to get in touch with his family in New York, he scrawled his message on a shirt collar instead. Here’s the text of the letter, as read by Benjamin Richmond of PRI’s Afropop Worldwide, and creator of the podcast New York Pacific:

“Dear Wayland and Gussie: All safe but awfully scared. Frisco and hell went into partnership and hell came out winner—got away with the sack. Draw a line from Ft Mason along Van Ness Ave. to Market St., out Market to Dolores to Twentieth, thence to Harrison, 16th & Potrero Ave., R.R. Ave. to Channel St. and bay. Nearly everything east and North of this boundary line gone, and several blocks west of it, especially in Hayes Valley as far as Octavia St. from Golden Gate Ave. east. Fire is still burning on the northside but is checked in the Mission. I and a band of 40 or 50 volunteers formed a rope and bucket brigade, back-fired Dolores from Market to 19th, pulled down houses and blanketed westside Dolores and won a great moral victory.

More with paper and stamps. James G. Jones

April 21st, 1906”

Benjamin Miller: I love the economy of language in this letter—if you go online and look at a picture of the shirt collar, you’ll see that the words are really crammed together. Necessity is the mother of invention. I’ll also say that I’m not sure I would sound so matter-of-fact and nonchalant after living through one of the worst natural disasters in American history. Well done, James Graves Jones.

The American Antiquarian Society’s mummy linen

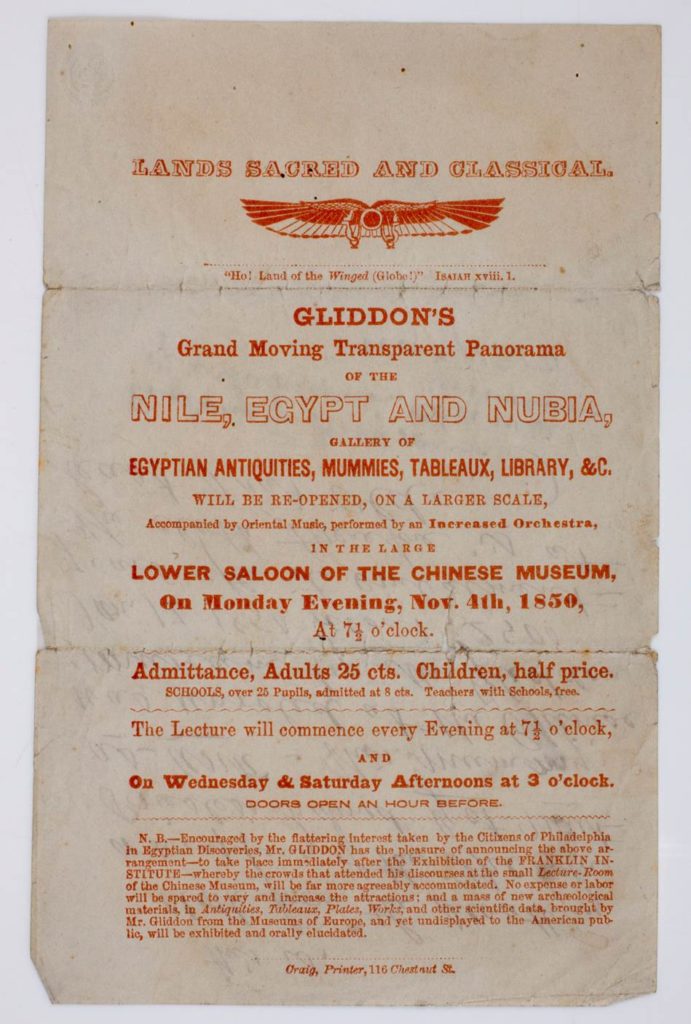

Lands Sacred and Classical handbill printed by Jared Craig, 1850. 7 by 5 inches. American Antiquarian Society.

“Mummy linen from around 800 BC is not what most visitors expect to see when visiting the American Antiquarian Society.”

Benjamin Miller: Next up, we’re going to travel back to the mid-nineteenth century, but this story actually concerns an object far, far older than that. So, join me in embracing your inner Egyptologist.

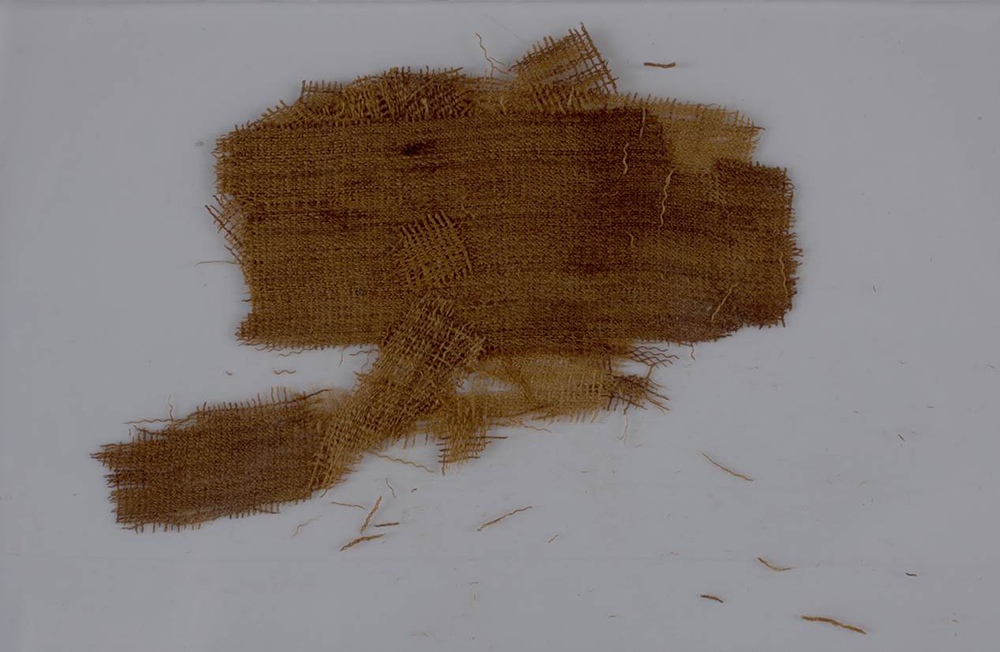

Lauren Hewes: This is Lauren Hewes, the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts at the American Antiquarian Society. When The Magazine ANTIQUES recently asked participating libraries and museums to share “curious objects” from our collections on Instagram, I immediately thought of this 1850 handbill in our collection. The seven-inch-by-five-inch piece was acquired in 2011 and was a reminder of the powerful stories that ephemera can tell us. Information about the wonders of ancient Egypt reached American in the early nineteenth century after European travelers and scientists began publishing narratives and exploration findings, including their work with the Rosetta Stone to crack the mysteries of hieroglyphics. Egyptian influences and motifs soon appeared in American architecture, furniture, and costume design. American authors like Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Louisa May Alcott all included mummies, pyramids, and sphinxes in their writings. In the middle of this Egyptomania, in 1850, George Glidden, former US vice-consul in Egypt traveled around America with four mummies and a rolling panorama of the Nile. He displayed the panorama and unwrapped a mummy before his audiences, all while lecturing on Ancient Egypt and discussing mummification. American audiences were fascinated by this spectacle and flocked to Glidden’s presentations. On November 23 in 1850, he was in Philadelphia where he unwrapped a female mummy and distributed the wrapping linen to his spectators. An anonymous audience member preserved a scrap of the linen from that mummy inside the handbill as a memento of the event. Mummy linen from around 800 BC is not what most visitors expect when visiting the American Antiquarian Society to do research on American history and culture. Combined with the handbill, however, this, “curious object” neatly encapsulates the nation’s nineteenth century fascination with Ancient Egypt.

Fragments from the wrappings of the Egyptian mummy of Got-Mut-As-Anch, c. 700 BC. Linen. American Antiquarian Society.

Benjamin Miller: Thanks so much to Lauren and to the American Antiquarian Society—@americanantiquarian on Instagram.

S. J. Shrubsole’s inkwell

Inkwell that belonged to Edward Capell and John Collins, editors of Shakespeare, by an unknown maker, 1781. Silver; height 1 ½, diameter 2 7/8 inches. Collection of Tim Martin.

“This was owned by two very important eighteenth-century editors of Shakespeare, Edward Capell and John Collins, who labored to restore Shakespeare’s texts from various bastardized versions.”

Benjamin Miller: I have one more segment for you, and this one, I’ll admit, does involve some nepotism. This is a very curious and very academic object posted by Tim Martin, the owner of the shop where I work, S. J. Shrubsole. We’re on Instagram as @sjshrubsole. Tim is one of the world’s top experts in antique silver, and he also happens to be an English major. So, when, as a dealer in his early twenties, he found a piece of eighteenth-century English silver with a connection to Shakespeare, it’s no surprise that he had to buy it. This is a small cylindrical box with an engraved inscription in Latin on its base. To my eye, this is a quintessential curious object—it’s a piece more rare than it is valuable, more perplexing than it is beautiful. It piques your curiosity and speaks to a strange and distant time, place, and people. Here’s Tim:

Tim Martin: So, I bought this ink stand at Tepper Galleries, a now-defunct auction house on 26th Street between Park and Lexington that I used to go to every Saturday morning to check their sales. They rarely had anything, but occasionally some oddity would turn up, and sometimes some lovely piece of commercial silver. This piece sort of mystified me at first because I had just started working at Shrubsole and I didn’t quite understand what it was. It had sort of an unusual form and didn’t look like an ordinary ink stand to me. The thing that caught me . . . caught my interest, of course, was the connection to Shakespeare. It was owned by—or passed from one to another of—these two very important eighteenth-century editors of Shakespeare, Edward Capell and John Collins, two people who labored to restore Shakespeare’s texts from various bastardized versions that had been . . . where the plays had been altered to make them more appealing to modern audiences. My Latin is terrible, so I didn’t know what the bottom inscription said, but I was sufficiently interested to buy it. And I had a friend who is a classicist who did translate it for me, but he had some trouble with it because I guess the Latin isn’t entirely . . . sort of . . . standard, classical Latin. But I don’t remember what my friend told me. I didn’t record it in any way. It was sort of pre-Internet, so I got it all, like, over the phone and wrote it down on a bit of paper that I subsequently misplaced. So, yeah. I mean, it’s a curious object and it’s still a curious object to me because, to be honest, I don’t really know what the inscription says. But I’ve always held on to it because I thought it was such a cool thing.

Benjamin Miller: Any Latin scholars out there looking for a little project? Maybe you can give Tim a hand.

An enormous, bottom-of-my-heart thank you to everyone who joined in this celebration of curious objects—those who were featured today and all the others who shared their fascinating objects and stories on Instagram. I’d like to thank our sponsors once more: Reynolda House Museum of American Art and Freeman’s Auction. And, of course, thanks to all of you listening right now, who make this whole project worth doing. Don’t forget to subscribe, rate, and review! Today’s episode was produced and edited by Sammy Dalati. Our music is by Trap Rabbit. And, until next time, I’m Ben Miller.

For more Curious Objects with Benjamin Miller, listen to us on iTunes or SoundCloud. If you have any questions or comments, send us an email at podcast@themagazineantiques.com.