A member of the first group of Japanese who, starting in the late nineteenth century, immigrated to the United States—known as the Issei generation—Takuichi Fujii left his childhood home in Hiroshima for Seattle in 1906 at age fifteen and eventually started a business as a fish seller. At some point and apparently without training—beyond the tutelage in ink-and-brushwork that most every Japanese grade schooler receives—Fujii took up painting and drawing. His artwork first appeared in public in 1930 as an entry in the Seattle Art Museum’s juried Northwest Annual exhibition. Fujii painted in the loose realist style associated with the artists of the American regionalist school, in watercolor mainly and occasionally oil. His work appeared regularly in the SAM shows throughout the 1930s and in group exhibitions as far afield as San Francisco, Chicago, and New York. In the middle of the decade, SAM’s director even considered giving Fujii a solo show.

Fujii’s work appeared in the Northwest Annual of 1941, which closed in November. A month later came Pearl Harbor, and soon after followed Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, directing all those of Japanese descent living on the West Coast to report for relocation as a wartime security measure. Fujii and his family would eventually end up among some thirteen thousand people held at a camp in Minidoka, Idaho. (Another internee at Minidoka was architect and future studio furniture master George Nakashima, who learned traditional woodworking while there.)

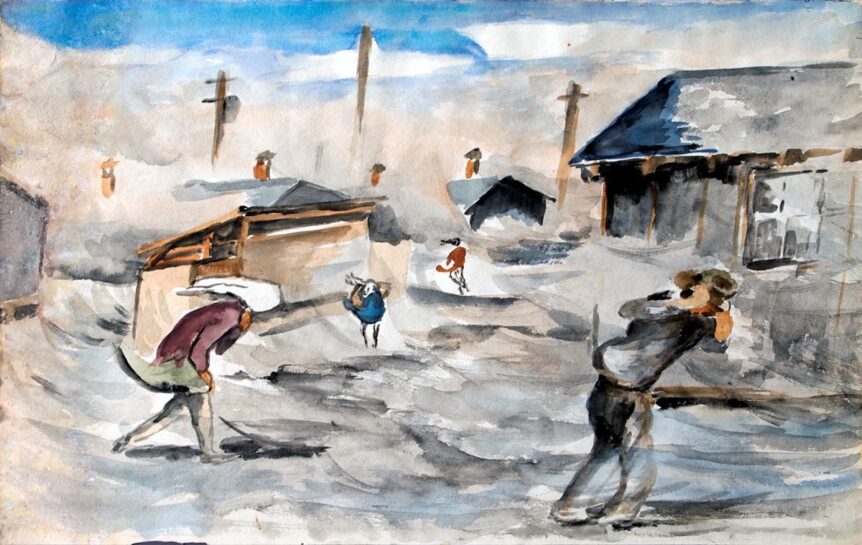

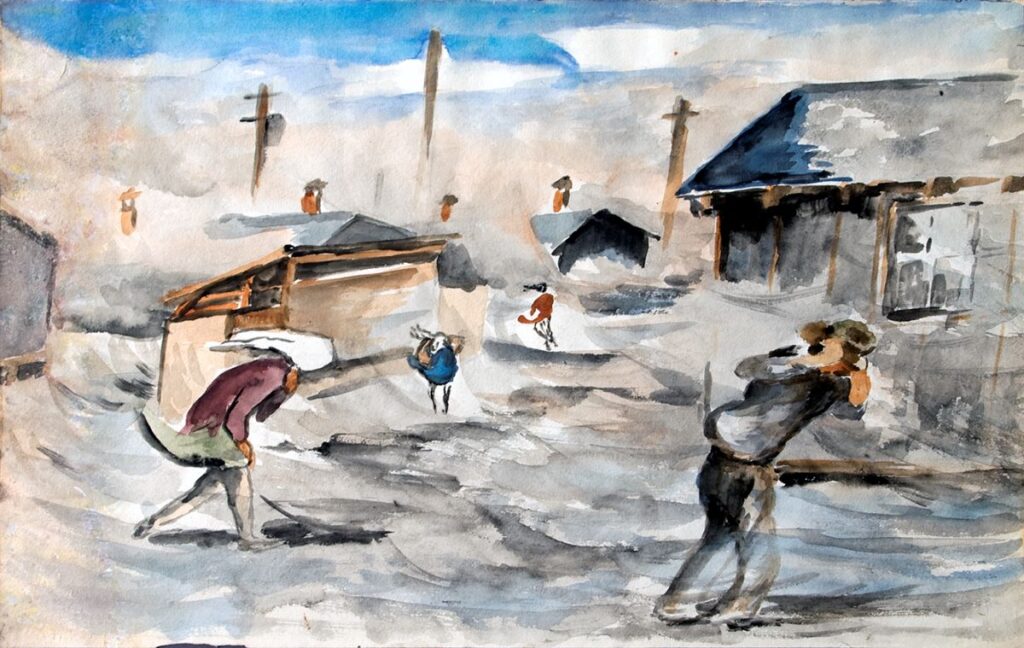

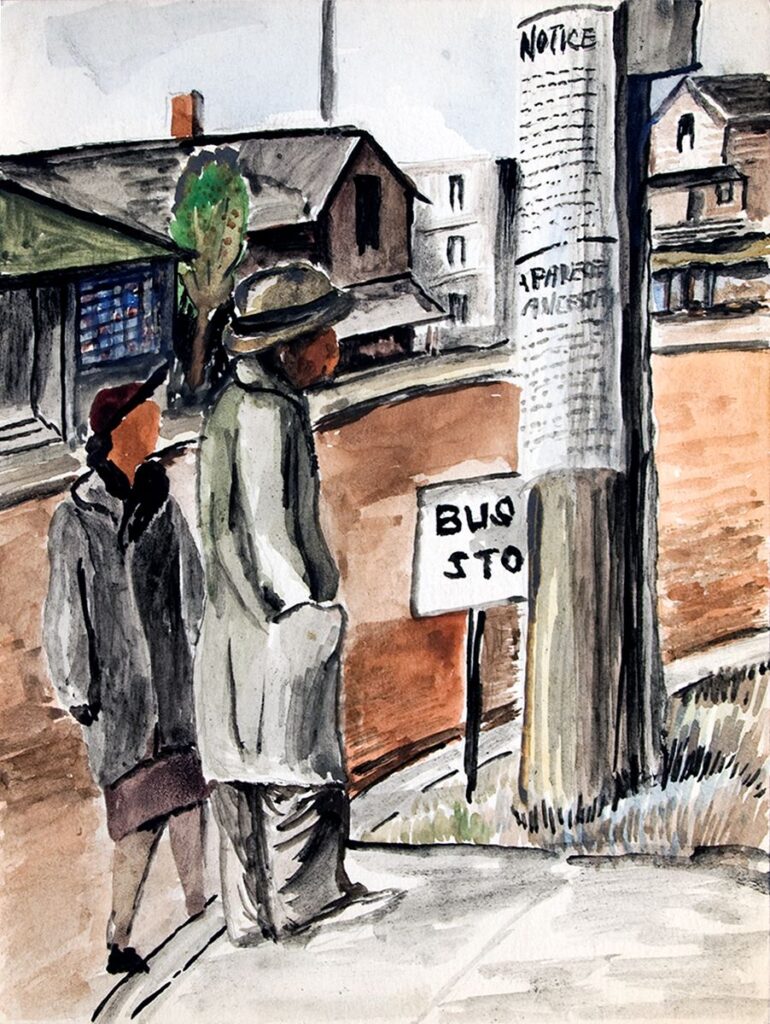

While incarcerated, Fujii began to keep an illustrated diary, which would end up nearly four hundred pages in length by the time the camp closed in 1945. Along with it, Fujii painted some 130 watercolors—a visual record of a dark period in American history that still has resonance today. These begin with the depiction of Japanese in Seattle staring at a copy of Order 9066 pasted to a telephone pole, and move on to include scenes of life in the dusty, windblown encampment, as well as wistful views of the world beyond the barbed wire.

The internment camp watercolors form the bulk of the eighty-two artworks on view in the traveling exhibition Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii, curated by Barbara Johns, the author of The Hope of Another Spring: Takuichi Fujii, Artist and Wartime Witness. The show is now on view at the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, located a few miles inland from downtown Delray Beach, Florida—a contemplative oasis of culture amid the surrounding landscape of strip malls and retirement communities.

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii • Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, Delray Beach, Florida • to October 6 • morikami.org