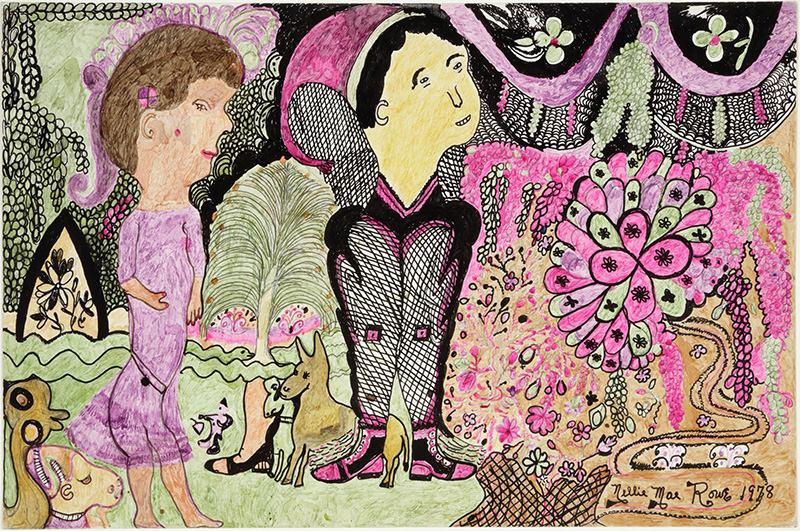

In the aptly titled exhibition Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe at the High Museum of Art, joy takes center stage. The nearly sixty works by Nellie Mae Rowe in the show—drawn from the museum’s collection—are jubilant, both in color and form. The playfulness of the works comes largely from the last fifteen years of Rowe’s life, when the self-taught artist, who lived just outside of Atlanta, Georgia, created her “Playhouse”—her home and studio space—which she decorated with found-object installations, handmade dolls, chewing-gum sculptures, and hundreds of drawings.

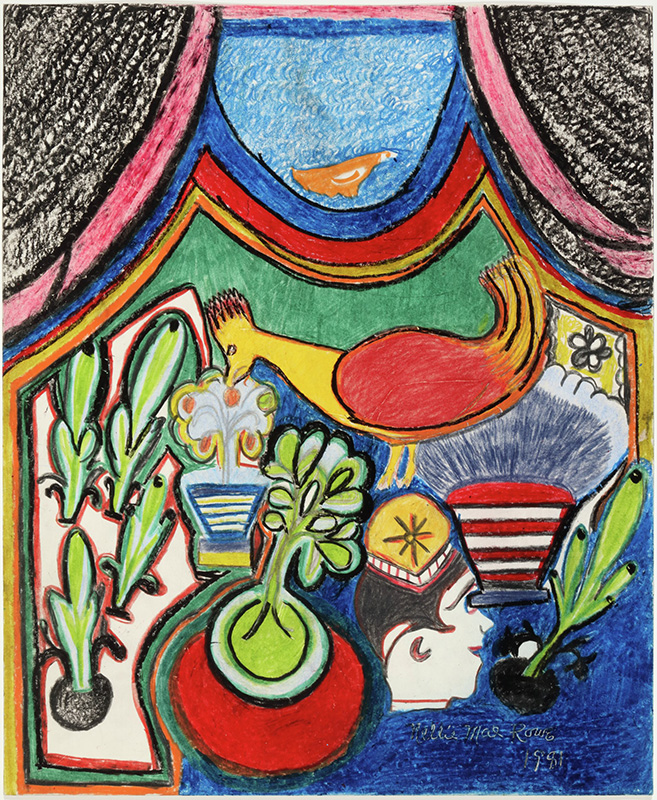

Rowe’s works are unabashedly bold and range in stylistic complexity. Untitled (Pecking Rooster), for instance, with its brilliant colors and whimsical central figure would make any viewer smile. Its straightforward but abstracted use of form comfortably rivals Picasso’s Le Coq and might be even more delightful. Untitled (Pig on Expressway) and Happy Days are more compositionally dense but equally enjoyable abstractions of familiar animal companions.

Katherine Jentleson, the High’s Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art, notes that Rowe made a decision “in the late 1960s, after she was widowed twice and her employers died, to not be in service to anyone else but herself. After spending her whole life caring for her husbands and white families, that was a radical choice in itself, but what she did next was really courageous—filling her home and yard with art in ways that were very visible and inviting hundreds of people, most of them white, into her home to enjoy her art. . . The way that she demanded respect and visibility through her art and the generosity she showed to the people who came to her doorstep to meet her, that was truly radical.”

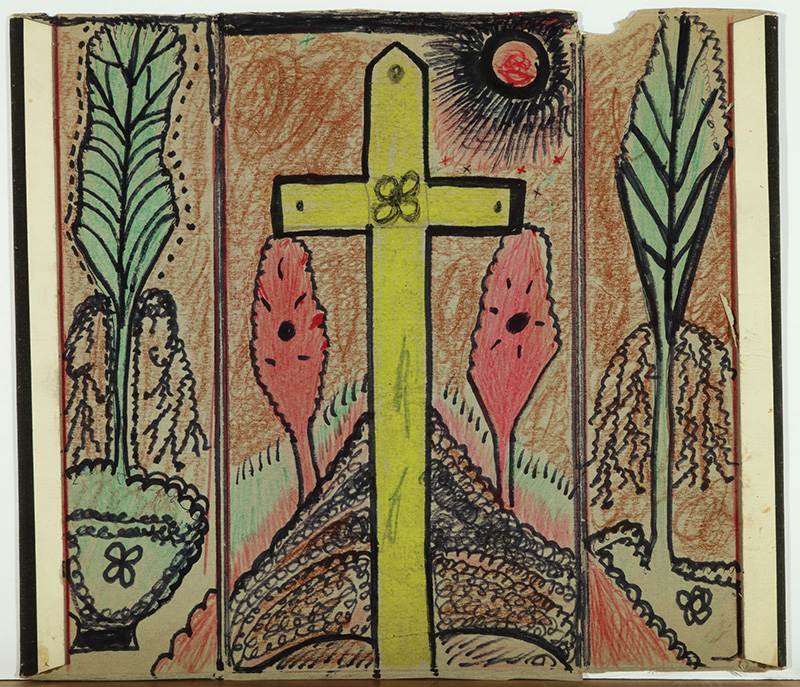

Rowe was a confident and inspired artist; in a 1982 interview with the late Atlanta gallerist and patron Judith Alexander, Rowe said: “I don’t know why He [God] put me here but He has me here for something because I don’t draw like anyone else; I don’t try to draw like anyone else. I see what I draw in my mind late at night and I don’t care how crazy it is, I’ll probably draw it.” Works such as Untitled (The Angel and the Devil’s Boot) and Untitled (Cross and Trees) demonstrate this determined and divinely driven call to create. As the interview ends, Rowe says, “All my dolls, chewing gum sculptures, everything will be something to remember Nellie. If you will remember me I will be glad and happy to know that people have something to remember me by when I’m gone to rest.” There is no shortage of happiness in Rowe’s work, and exhibition viewers will come away not only glad to remember her, but grateful to know her—and as we continue to work toward equity, let us not only work fervently to confront anti-Black racism but celebrate Black joy, too.

Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe • High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia • from September 3 to January 9, 2022 • high.org