Impressionism was somewhat slow to gain a hold on the American consciousness, among both the public and most artists. Manet, Cézanne, and Pissarro were displaying their work in the 1860s; the first official impressionist exhibition in Paris took place in 1874. But it was not until 1886 that the impressionists had an exhibition in the United States, in a show in New York City organized by a French art dealer. But once impressionism took root in American culture, it proved to be not only the most popular—and enduring— artistic style ever to captivate the nation’s art lovers, but also a style that was uniquely adaptable to the American scene.

A newly opened traveling exhibition currently on view at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee, titled America’s Impressionism: Echoes of a Revolution, demonstrates that, while they certainly learned from and were inspired by their French peers, American artists developed a style of impressionism that was entirely their own.

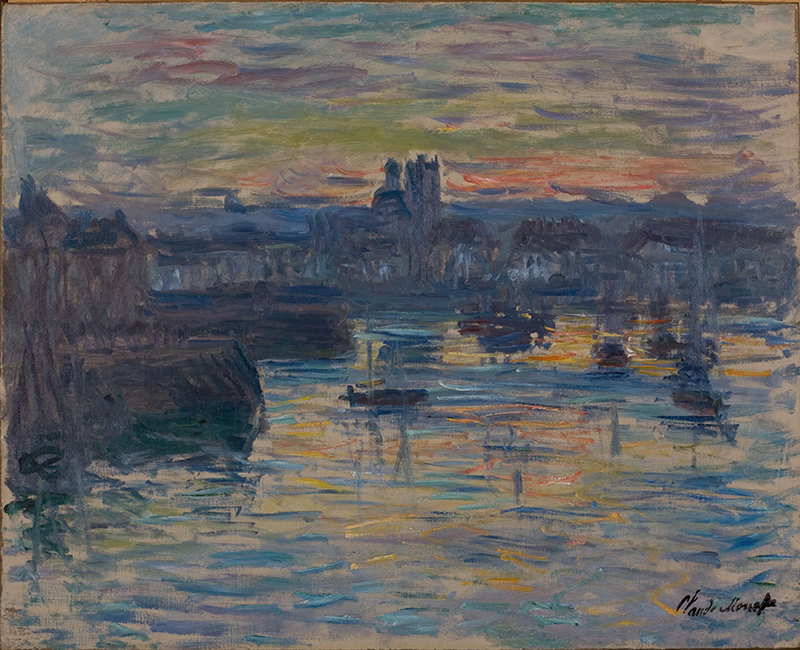

In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, foreign study and travel had become standard practice for Americans with artistic aspirations. The experience left them open to new ideas and techniques and, in the case of women—who were allowed to enroll at few American art schools, and even then with restrictions—studying in the for-profit ateliers of Paris was the only avenue to an artistic education at all. Claude Monet became a kind of patron saint for the Americans, and many made pilgrimages to his home in the country village of Giverny, hoping some of the French artist’s greatness would rub off.

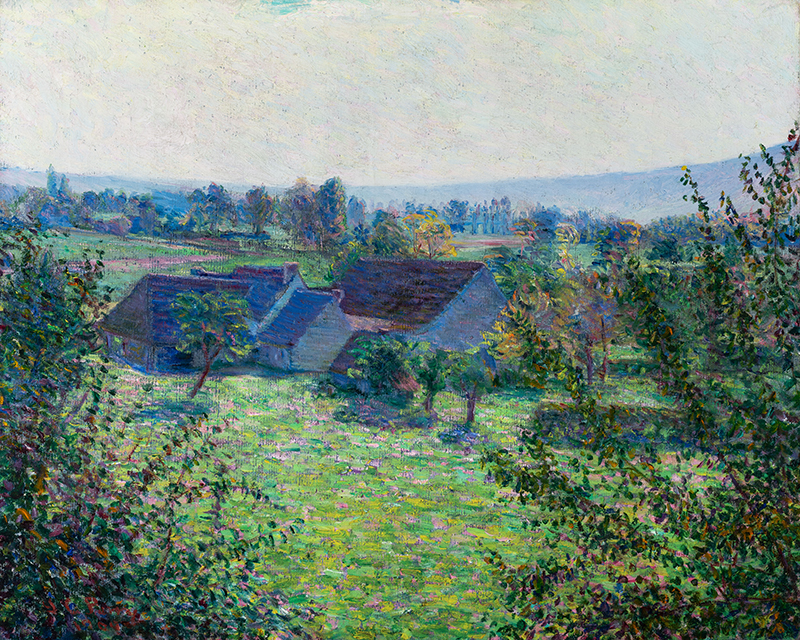

No doubt it had also not escaped their notice that Monet won an early following among American collectors. Rather than their urban scenes, it was the plein air landscapes of the French impressionists that first found favor among American aesthetes. From the dramatic and allegorical vistas of the Hudson River school painters to the moody views of the tonalists, by the later nineteenth century, landscapes had become the predominant and most popular genre in American art. Connoisseurs in this nation were primed to appreciate impressionist landscapes, and, what’s more, the style traveled well. Artists’ colonies sprung up in New England and on Long Island, and from them came pastel-colored visions of wildflower-filled fields, rolling surf on the shore, and mountainside meadows. There would be impressionist artists in Texas and the Southwest, painting prairie scenes and cattle drives. Impressionists in California created nostalgic views of Spanish mission towns, and the beauty of the rugged coastline around the Monterey Peninsula lured artists from the East, such as Childe Hassam.

Above all, the exhibition’s curators argue, what made impressionism such a popular and enduring style in America was its inherent sentimentality—by which they mean not a syrupy or maudlin sensibility, but that the paintings were easy to understand and appreciate. A viewer need not be schooled in classical mythology, nor arcane Biblical stories to comprehend what was depicted. Impressionist paintings romanticized quiet moments in everyday life; these artworks were gentle, soothing, and comforting. Even when the realities of labor and industry intrude on the impressionist landscape—as in J. Alden Weir’s Factory Village (1897), which depicts a thread-making mill in a Connecticut town—they are rendered serene and even picturesque. American impression was, perhaps, a form of escapism.

This exhibition will travel to the San Antonio Museum of Art and the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Please consult the websites of those institutions for show dates. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog—the lead author is Amanda C. Burdan, curator at the Brandywine—distributed by Yale University Press.

America’s Impressionism: Echoes of a Revolution • Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tennessee • to May 9 • dixon.org