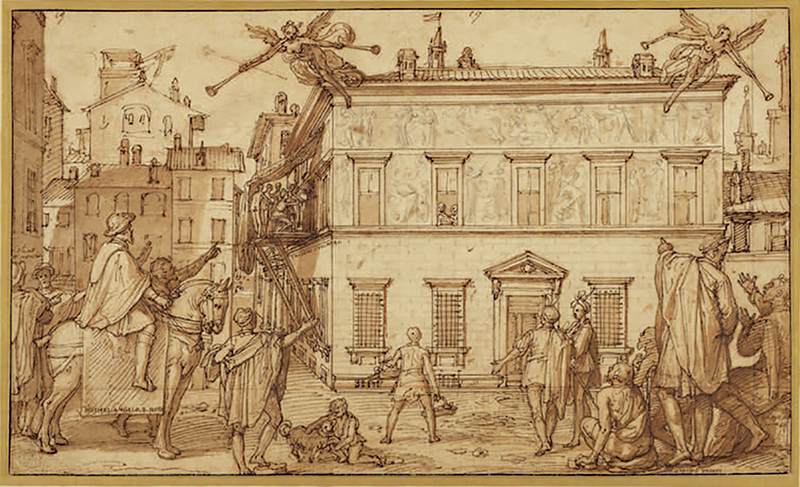

Right: Taddeo Drawing by Moonlight in Calabrese’s House by Zuccaro, c. 1595.

A forthcoming show of drawings at the Getty, The Lost Murals of Renaissance Rome, explores what was, in all likelihood, the biggest waste of time in the history of art. Few painters today adorn the facades of important public and private buildings for the excellent reason that—as you might expect—as soon as rain and sunlight hit the dazzling surface, the paint begins to fritter away, leaving only ghostly traces and then none at all.

But it took years, apparently, for the artists of the Renaissance, so wise in other respects, to awaken to this fundamental fact. In the meantime much was lost. Perhaps the most eminent example of such destruction is the frescoes completed around 1508 by Giorgione and Titian—who were roughly thirty and twenty years old, respectively, at the time–on the facade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice. In no time at all the damp and salinity went to work, ravaging the surface of the building, and thus largely depriving us of one of Titian’s earliest and Giorgione’s latest masterpieces.

Rome’s facades—the focus of the Getty show— fared somewhat better than Venice’s in the sense that, due to a slightly better climate, ruination could be put off a little longer. Indeed, a few surviving works offer some measure of reward—and a sense of what has been generally lost—to tourists willing to stray from the beaten path. The most significant figure in this line of work was Polidoro da Caravaggio, who, in collaboration with Maturino da Firenze, created the much faded but largely intact facade of the Palazzo Milesi in the Campo Marzio. Like many of the facades designed by Polidoro, this was based for the most part on friezelike processional scenes that reenact a typical Roman triumph. Polidoro used similar motifs on the facade of the Palazzo Ricci, although most of the painting has long since been effaced. In scarcely better shape is the so-called Palazzo Istoriato—part of the Palazzo Massimo complex off the Piazza Navona—whose artist, possibly a student of Daniele da Volterra, was clearly influenced by Polidoro.

But the new exhibition is mostly centered on a number of extraordinary drawings created around 1595 by Federico Zuccaro, perhaps the most successful artist in Rome, though not the best, in the final decades of the sixteenth century. In all of art history there may be no greater example of fraternal devotion than these images that Federico conceived to commemorate the life of his older brother Taddeo and that he hoped to bring forth on the walls of his sumptuous house on the Via Gregoriana.

That ambition was never realized. In tracing the ascent of his brother, a better painter than himself, from obscurity to success, Federico records Taddeo’s life with a specificity usually reserved for princes and popes, but never, before this, for painters. This glorification was in keeping with Federico’s lifelong mission to raise the status of painting to that of a liberal art. The titles well describe the drawings’ subjects: Taddeo Leaving Home Escorted by two Guardian Angels; Taddeo at the Entrance to Rome; Taddeo in the Sistine Chapel Drawing Michelangelo’s Last Judgment.

One of Federico’s drawings is of particular interest for the larger theme of the show: Taddeo Decorating the Facade of the Palazzo Mattei. This was the commission that established Taddeo, all of eighteen at the time, as a leading Roman painter. Unfortunately, although the palazzo still stands, Taddeo’s frescoes have been entirely destroyed and the facade covered over in plaster. A better fate awaited the faded but still largely intact facade of the Palazzo di Tizio da Spoleto in Piazza Sant’Eustachio—thought to be a collaboration between Taddeo and Federico. Better than any other building in Rome, this diminutive structure gives us a vivid sense of the colors and forms that once animated the misbegotten genre of the painted facade.

The Lost Murals of Renaissance Rome • Getty Center, Los Angeles • May 31 to September 4 • getty.edu