The traveling exhibition Calder–Picasso, which debuted at the Musée National Picasso-Paris in 2019 and arrives at the High Museum of Art this June, features more than one hundred works by the two twentieth-century masters. It is a testament to their fame that simply placing the names Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso in close proximity can evoke an immediate reaction—that is: run to the museum, reserve your ticket in advance. However, the pairing is not a particularly obvious one; their relationship, if the word is even to be used, is an aesthetic one—far from the complicated friendship-cum-rivalry of Picasso and, say, Diego Rivera. As the High’s curator of European art, Claudia Einecke, suggests, “we might think of the exhibition as a kind of non-verbal version of the artistic conversation that Calder and Picasso, by all accounts, did not have in person.”

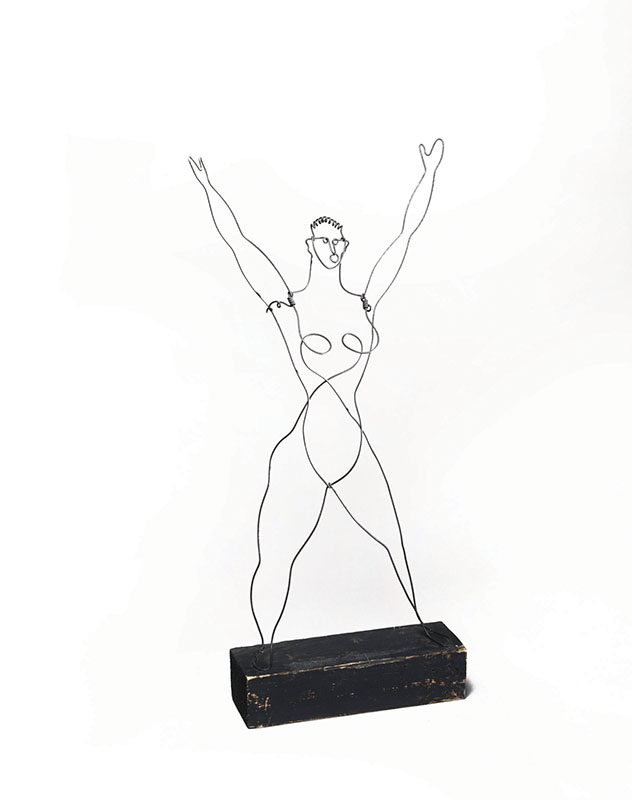

The curatorial through-line of the exhibition is the artists’ respective use of empty space—what Einecke calls the “void.” The theme manifests itself in Calder’s works as the absence of mass and the movement of his sculptural elements through space—shapes disappearing and reappearing as one walks around an artwork such as La Grande Vitesse, or the physical movement of his mobiles such as Croisière. Picasso’s approach was the reduction of figurative form, as in Bull’s Head (Tête de taureau), or Woman in an Armchair (Françoise Gilot). Einecke says of Calder’s Acrobat: “as an object, it consists of empty spaces (voids) that are minimally bounded by threads of wire. Together, wire and void form a convincing representation of a body moving in space.” By contrast, in Picasso’s Acrobat (Acrobate), it is the inclusion only of select masses—head, arm, legs—that creates the feeling of an ecstatic dance.

“Perhaps the most salient difference between the two artists (in the context of this exhibition) is that Calder, for most of his career, worked in abstract modes, whereas Picasso adhered to figuration, albeit in nonnaturalistic ways,” Einecke says. “This fundamental difference is obvious for anyone to see in the exhibition, without it being specifically addressed or deliberately emphasized in any of the groupings. The conceptual thrust of the exhibition is to show two artists exploring the void in their work, without necessarily comparing or contrasting their respective solutions.”

Before creating A Universe in 1934—a work similar in both form and function to Croisière—Calder is reported to have said, “Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.” Although this statement applies to his mobiles generally, it summarizes the experience of Calder–Picasso for a visitor to the show: your own movement around and between the works creates a conversation between Calder and Picasso. As museums begin to reopen in earnest after roughly a year of Covid-19 closures, dialogues created through curation remind us that museums are cultural composers.

Calder–Picasso • High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia • June 26 to September 19 • high.org