Shaker box, probably northeastern United States, c. 1827. South Union Shaker Village, Auburn, Kentucky; except as noted, photographs are by Mack Cox.

Underside of the box’s top, showing the signature of Hannah Freehart (c. 1803–1893). South Union Shaker Community, Auburn, Kentucky.

The Shakers were already deeply rooted in the northeastern United States by the time they sent three missionaries to what was then known as the “West.” Leaving New York on January 1, 1805, the men arrived in Kentucky two months later, finding the religious environment associated with the Great Revival ripe for converts to the Shaker faith. Within two years the Shakers established communities in Ohio and Indiana, and two in Kentucky—Pleasant Hill in 1806 and South Union in 1807.

The Speed Art Museum in Louisville, recently opened an exhibition, Careful, Neat, and Decent: Arts of the Kentucky Shakers, examining the material culture of the Shakers at both South Union and Pleasant Hill. From the furniture and objects the Shakers created for themselves to the products they marketed to the public, the exhibition gives visitors a unique opportunity to view a juxtaposition between the design sensibilities of the two villages. (A related video presentation—Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly: When the Spirits Moved Them, They Moved—employs modern dance to interpret Shaker life and religious ecstasy.) The exhibition also illustrates the stark difference between a nineteenth century Kentuckian’s interpretation of Shaker simplicity and that of the Shakers in the Northeast.

The Shaker lifestyle was a paradox of bold restriction and revolutionary freedom. To belong to the sect, you had to give up your property for the communal cause, be willing to confess your sins openly, and vow to live a celibate life. At the same time, the Shakers saw men and women as equals, bestowing governing power on both sexes in spiritual and temporal roles. They believed in racial equality and offered freedom within their villages that was unavailable to African Americans in the antebellum South. The Shakers established living environments that were clean, efficient, and modern for their day. Technology was embraced, easing the drudgery of work. Trades were taught, education was provided, and three meals a day were served in the large communal dining rooms.

While others who dwelt on the frontier had a constant focus on mere survival, the Shakers of Kentucky enjoyed relative peace and plenty. That sense of calm bred a culture of creativity. Overriding all was the Shakers’ sacred initiative. For the Shakers, daily tasks were opportunities to worship, and their constant goal was spiritual and material perfection. It was in this balance of inspiration and ingenuity that Shaker material culture was born.

Both of Kentucky’s Shaker villages were primarily inhabited by southern converts—Pleasant Hill’s from Kentucky, Virginia, and North Carolina; South Union’s from Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Adult converts possessed cultural biases, conveying their customary methods of architectural construction, foodways, and music-writing traditions into the Shaker communities. Southerners also talked differently, worked differently, dressed differently, and created furniture differently.

People joining the Shakers often brought with them furniture and household goods that the communities absorbed into their living and working environments. By the mid-1810s, however, there arose a need to produce household furniture for the growing number of members in both villages. The earliest furniture created by the Kentucky Shakers reflected a simplified, vernacular version of Federal period design with strong regional influence and a propensity for being slightly behind the times stylistically. Simple bracketed or cut feet on case furniture eventually transitioned, by the 1830s, to turned legs and the use of decorative moldings and beadings.

This evolution in design did not take place in the Shaker villages in the Northeast to the degree that was evident in Kentucky. South Union craftsmen seemed particularly aware of the popular stylistic trends taking place in the region surrounding the village. By the 1850s they were making beds and tables that incorporated turnings typical of the Empire period. Pleasant Hill craftsmen were not. In fact, Pleasant Hill seemed to revert to simpler turnings by the 1850s, creating tables and case furniture with unadorned, cylindrically turned legs. During the same period, South Union chose to employ an even greater use of decorative turnings. It is possible that South Union’s geographic distance from Shaker leadership at Mount Lebanon, in upstate New York, enabled the community to utilize greater creative license.

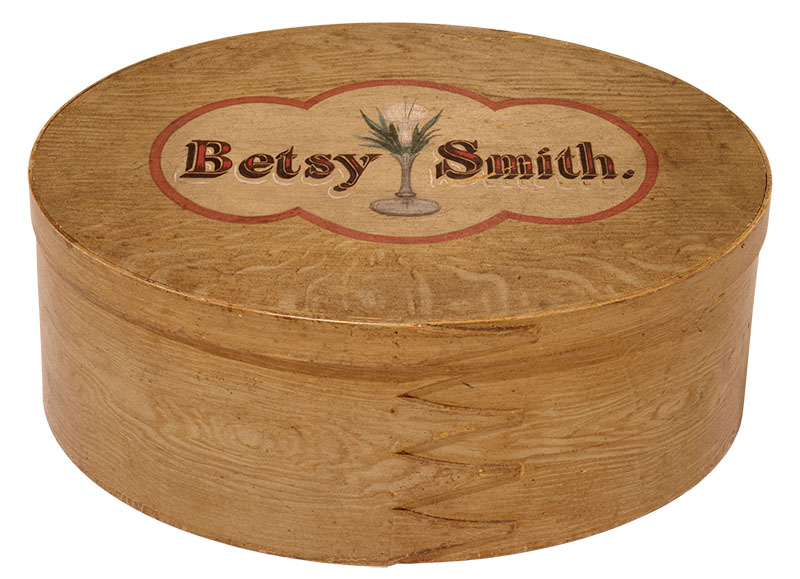

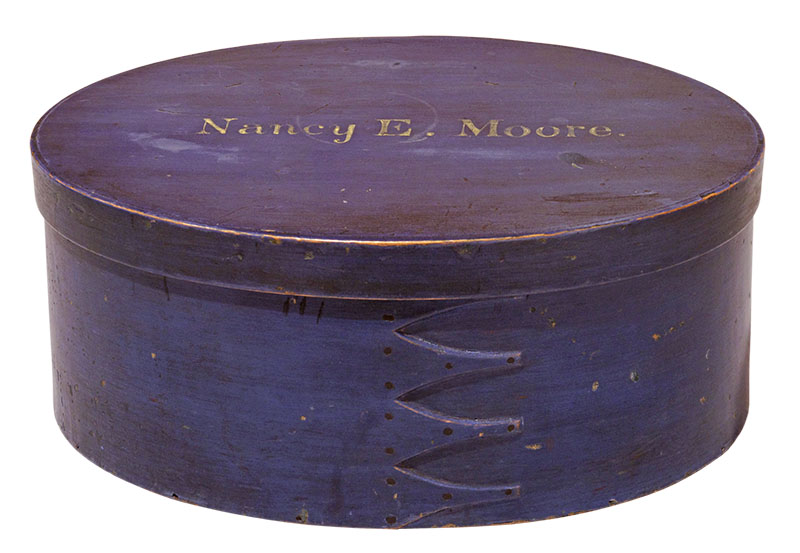

The use of color in America’s Shaker villages may surprise some who equate the sect with a prosaic existence. Brilliant silk kerchiefs, vivid woven coverlets, and brightly painted oval boxes and baskets are reminders that the Shakers did indeed often prefer vibrant color on the objects they used and within the buildings they inhabited. Two highly decorative oval boxes from South Union, one belonging to Eldress Betsy Smith and the other to Eldress Nancy E. Moore, are thought to have been gifts from a visit to the Northeast in July 1854. They are on view together at the Speed Art Museum for the first time.

By the early twentieth century, the Shaker movement in America was only a remnant of what it had been during the previous two centuries. Pleasant Hill closed in 1910 and South Union in 1922. Thankfully, a considerable amount of material culture from both villages has survived, exemplifying a distinctive subset of Shaker artistry and creativity. When Shaker leadership distributed the tract A General Statement of the Holy Laws of Zion in 1840, it stated: “Whatever is fashioned, let it be plain and simple, and . . . unembellished by any superfluities, which add nothing to its goodness or durability.” The Kentuckians obviously interpreted that rule differently from their counterparts in the Northeast, creating objects in an environment of relative isolation, with a slight sense of autonomy, and within the stronghold of regional tradition.

— Tommy Hines, director of the South Union Shaker Village in Auburn, Kentucky

Careful, Neat, and Decent: Arts of the Kentucky Shakers • Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky • to March 14, 2021 • speedmuseum.org