When Leonardo’s masterpiece Mona Lisa went on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1963, more than a million people lined up to see the painting in just one month’s time. While it’s unlikely that a single work of art will ever again be such a draw, there is a good chance that among the thousands who visit the Met’s current exhibition Manet/Degas, many will be there primarily to see one painting that has never traveled to the United States before: Olympia—Édouard Manet’s famed, scandal-making 1863 nude full-length portrait of a Paris courtesan, her maid, and her fidgety cat.

To be sure, there are many more great works of art to be seen in Manet/Degas, a show—comprising works brought together from the holdings of several museums, primarily the Met and the Musée d’Orsay, where it debuted earlier this year—that examines impressionism through the lens of the longtime friendship and rivalry between the two artists principally responsible for giving life to that art movement.

Manet and Edgar Degas were both products of wealthy, upper-class Parisian families, yet could not have been more different in personality and temperament. Manet was charming, gregarious, and liked by even those who did not appreciate his work. Degas was secretive, shy, and fussy. (Two self-portraits in the exhibition tell the story: Manet sports a dark yellow jacket and a hat set at a jaunty angle; Degas, dressed all in black, looks sullen and peevish.) Still, after the two met, as the story goes, at the Louvre while sketching the same painting, they formed a deep bond and a relationship that became an endless cycle of argument and reconciliation.

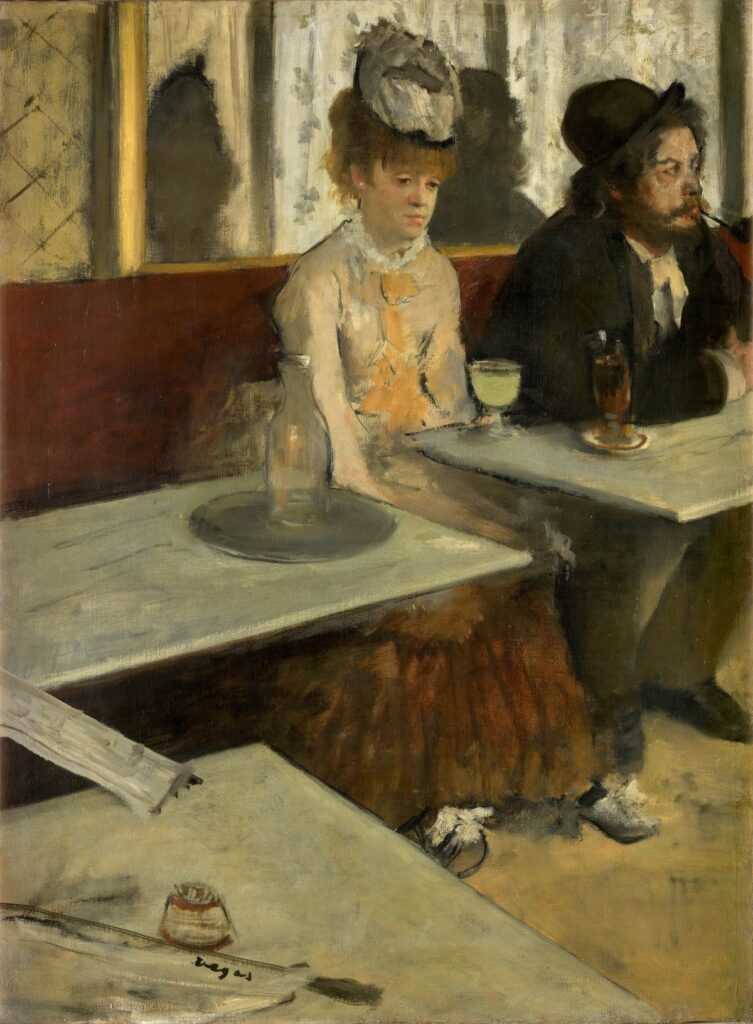

Manet/Degas seeks to demonstrate the ways the two influenced—and sought to one-up—each other through their respective treatments of the same subjects. These include portraits, racetrack scenes, depictions of women bathing, portrayals of alcoholic despair—Manet’s Plum Brandy and Degas’s superior, powerfully moving In a Café (The Absinthe Drinker)— and family group portraits. The artists’ contrasting personalities are most evident in the last set. The scene in Manet’s The Balcony is sunny and forthright, while the subjects of Degas’ Family Portrait (The Bellelli Family) seem uncomfortable and remote. And if something appears wrong with Degas’s Monsieur and Madame Édouard Manet, there is: Manet so disliked the depiction of his wife, Suzanne, that he sliced off most of her section of the canvas.

Incidentally, the nude woman in Olympia was not, as is generally thought, a prostitute herself. She was Victorine Meurent, a professional artist’s model and an artist herself, who won membership in the prestigious Société des Artistes Français and whose work was shown numerous times at the Paris Salon.

Manet/Degas • Metropolitan Museum of Art • to January 7, 2024 • metmuseum.org