Often overlooked and frequently misunderstood, women artists have often gotten less than fully informed treatment from critics and scholars. For every instant star like a Georgia O’Keeffe, there’s an Alice Neel, who painted for decades before her genius was appreciated.

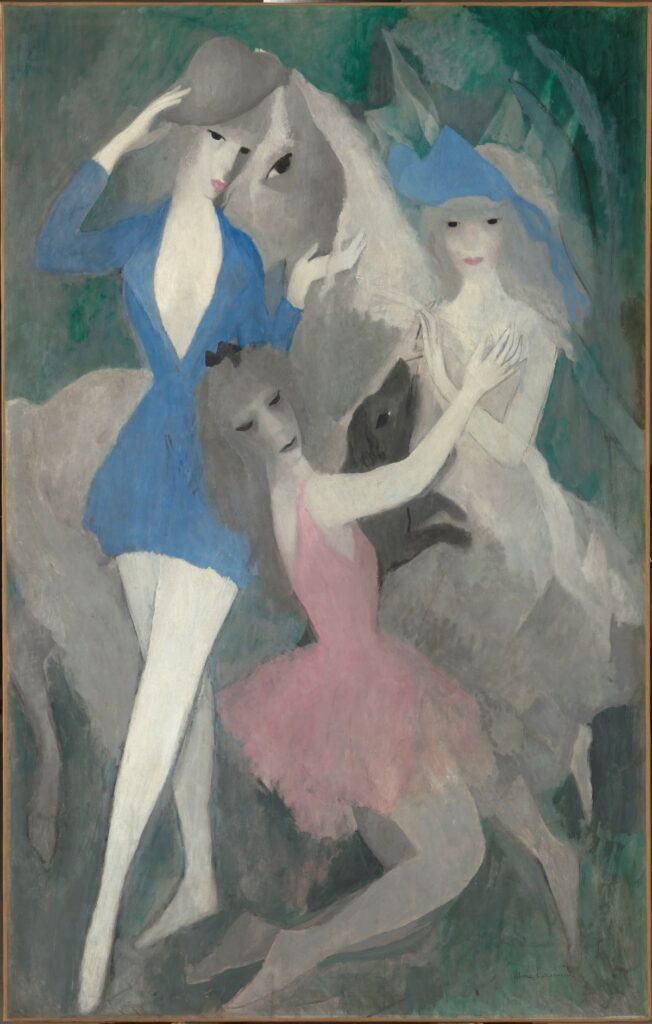

The French artist Marie Laurencin enjoyed a full and highly visible career, but still remains something of an unknown quantity. Raised in Paris by a single, working-class mother, Laurencin studied at the Académie Humbert, where she met artists Georges Braques and Francis Picabia. She ran in their circle, along with those of Pablo Picasso and other members of the cubist crowd in Paris in the early decades of the twentieth century, although her own artistic style diverged considerably from theirs. She exhibited her work regularly. Gertrude Stein was an early collector and her work was included in the 1913 Armory Show. (Picasso had pitched her to the exhibition’s co-organizer, painter Walter Kuhn.) Laurencin also illustrated several books (including a 1930 edition of Alice in Wonderland) and designed decor for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and the Comédie-Française.

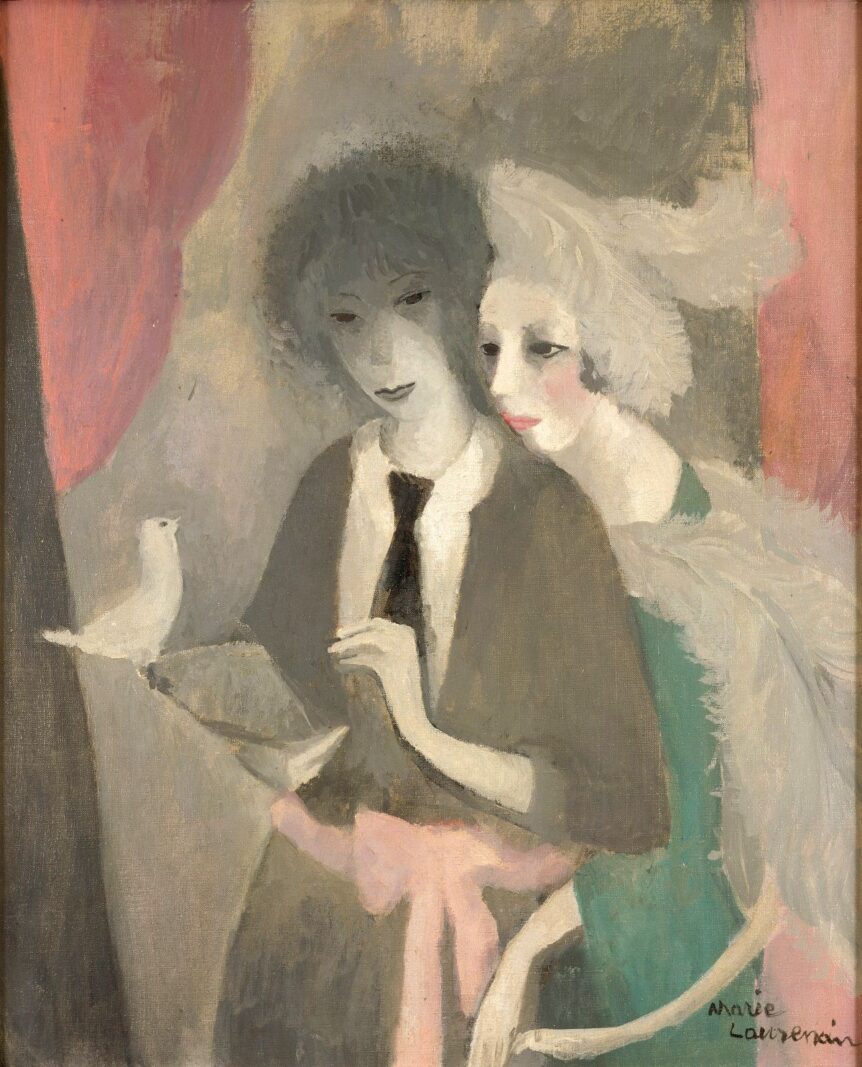

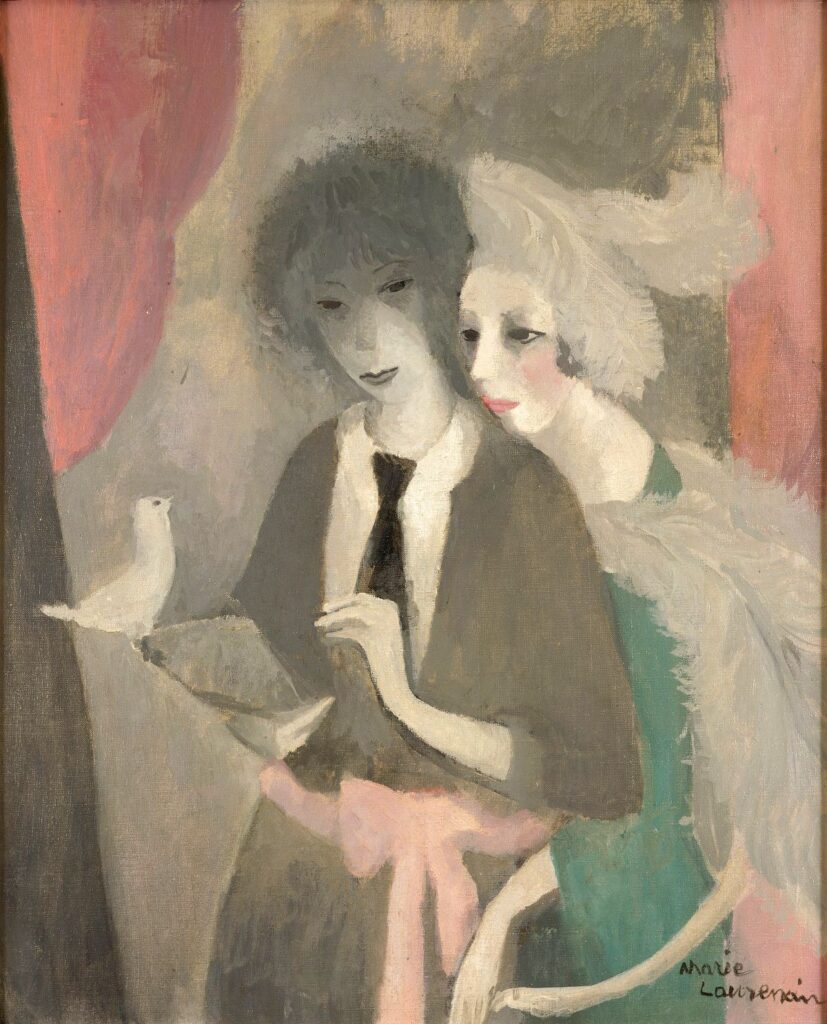

Her paintings—diaphanously rendered images of women executed in pastel hues, many of them dark-eyed figures in loosely defined landscapes and interiors—are not easily situated in a standard reading of modernism. Laurencin’s sexual ambidexterity undoubtedly influenced her choice of primary subjects. She had relationships with both women and men. A lover and muse of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, Laurecin was also a regular at the literary salon hosted by expatriate American heiress and writer Natalie Clifford Barney, who had moved to Paris so she could live openly as a lesbian. Laurencin’s focus on women, and the “feminine” manner in which she rendered her subjects, can be seen as a subversive strategy that allowed the artist to penetrate the male-dominated art world while giving full expression to her interest in the autonomy and intimacy of female relationships.

With the exhibition Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris, the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia does a deep dive into the artist’s oeuvre and the world in which she operated. The first major show since Marie Laurencin: Artist and Muse at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama in 1989, Sapphic Paris was organized by Barnes curator Cindy Kang and consultant Simonetta Fraquelli. It is the latest in a series of exhibitions at the Barnes devoted to under-recognized women artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Previous outings focused on Suzanne Valadon, Marie Cuttoli, and Berthe Morisot.

“Marie Laurencin, like other historical female artists that have benefited from recent reassessments, has turned out to be much more fascinating and important than traditional art historical accounts have suggested,” Kang says. “She has conventionally been understood as a secondary figure within the narrative of cubism and the avant-garde, however our project seeks to incorporate the perspectives of queer studies and highlight the context of the sapphic circles she frequented. Her artistic contributions to this alternative vision of modernism are significant.”

Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris • Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia • to January 21, 2024 • barnesfoundation.org