Is it possible that, by honoring paintings in our contemporary, almost idolatrous, fashion, we do them a disservice? That seems to be the subtext of a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits of the Renaissance, which is, when all is said, a foray into the very objecthood of a painting, especially one by an Old Master. Containing some sixty works of art, mostly paintings but also bronze medallions, the show makes a persuasive case for a fascinating and little-known subchapter of Western art: the frames, boxes and even curtains that often concealed early paintings.

When the modern museumgoer sees a work in a gallery, it is apt to seem transubstantiated, even dematerialized: it has become one with the flat surface that contains the image. Notwithstanding the thick impasto typical of the New York school abstractionists, the work’s material, tactile essence seems almost beside the point as we engage with it through the medium of sight alone.

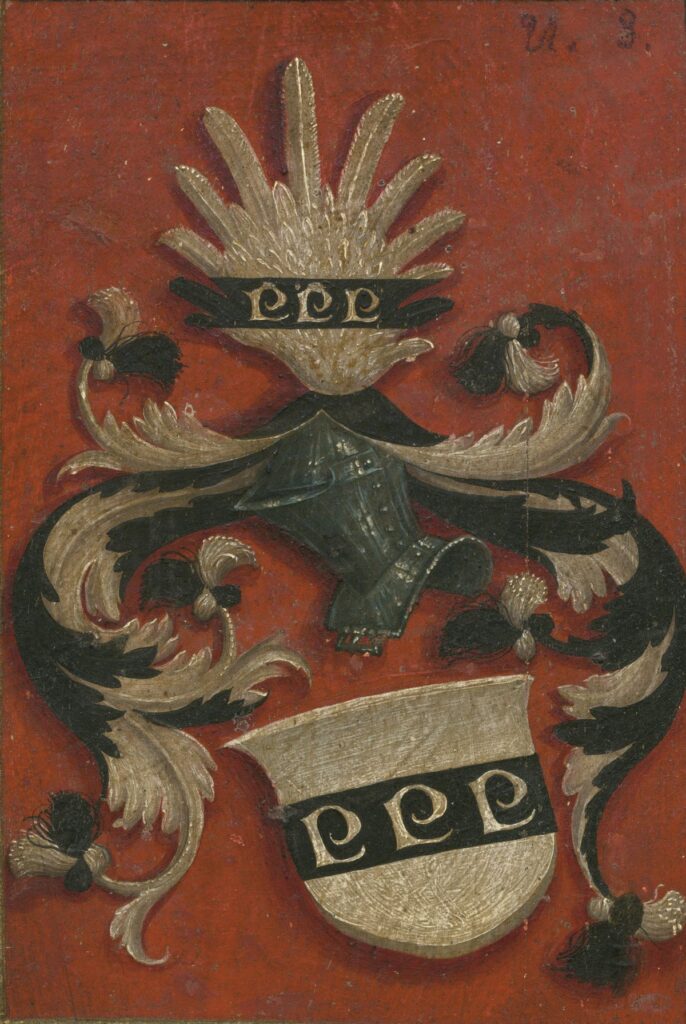

But for much of the history of Western art, the painting was also its material presence, whether that meant the painted frame that surrounded it or the wooden case or silk curtain that concealed it, or the wings that folded over a diptych, or the fact that the back of an image was apt to be painted, often very well indeed.

Undoubtedly the image facing the viewer, the image that lay within the frame, was the main event, while the various other elaborations were mere handmaids of its artistry. But that very fact enabled the artist, in those ancillary portions, to push beyond the severe strictures of the Old Masters and so to produce something startlingly new. The primary image, as in all Old Master paintings, obediently respects the established rules: the works on view at the Metropolitan are almost invariably fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian, German, and Netherlandish portraits; but in the secondary elements, the Old Masters have gone on holiday, allowing themselves liberties they would never countenance in a standard studio product.

Often the artist attempts trompe-l’oeil effects, especially by imitating marble or porphyry. At other times, the obverse of a painting is inscribed with a finely lettered Latin devise. But sometimes the artist proves to be far more ambitious. Perhaps the most consequential example at the Met is the obverse to Hans Memling’s fine but conventional Portrait of a Man from the 1480s. On the other side, the artist has depicted a brilliant still life of a vase with flowers. If this is not the first independent still life in Western painting it is very nearly so, and it is without parallel.

Often the secondary image was an allegory, like those that Lorenzo Lotto painted for his Portrait of Giovanna de’ Rossi and his Portrait of a Woman Inspired by Lucretia. Neither allegory would have been possible on its own, but the context of the portrait seems to have given the artist permission to follow his personal inspiration.

Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits of the Renaissance • Metropolitan Museum of Art • April 2 to July 7 • metmuseum.org