The term Harlem Renaissance, as it is used in a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a metaphor. Obviously, the show has much to do with the area of Manhattan just north of Central Park, where many of its some 160 objects—paintings and sculptures, as well as film, photography, and ephemera—were produced. But it ranges far beyond that designated geo- graphical boundary all the way to Paris, Berlin, and Cuba, among other destinations.

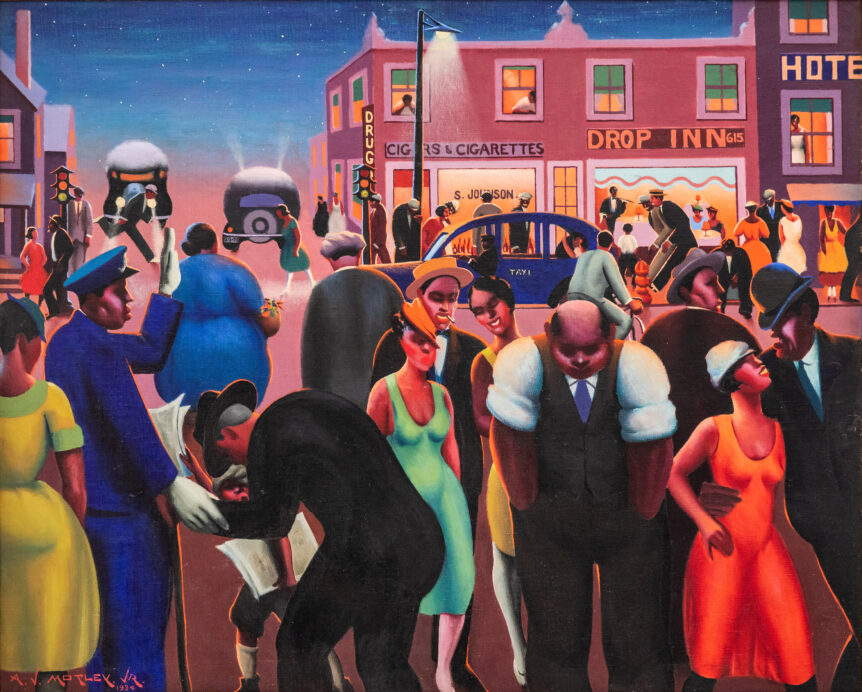

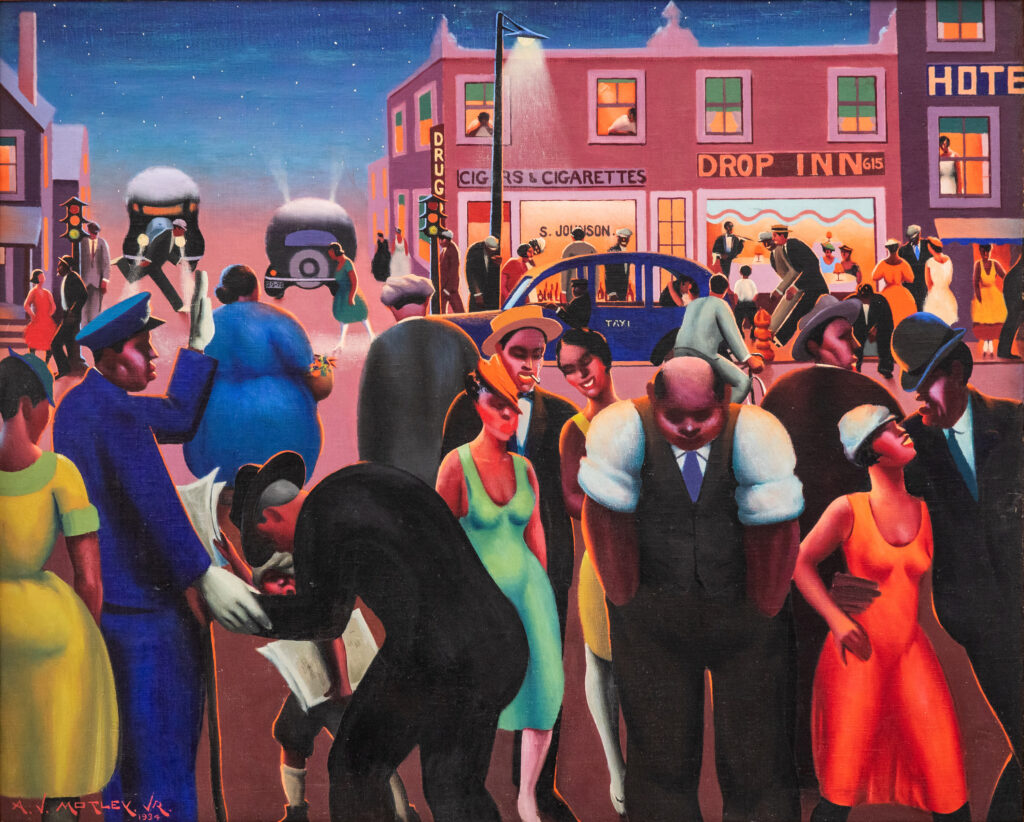

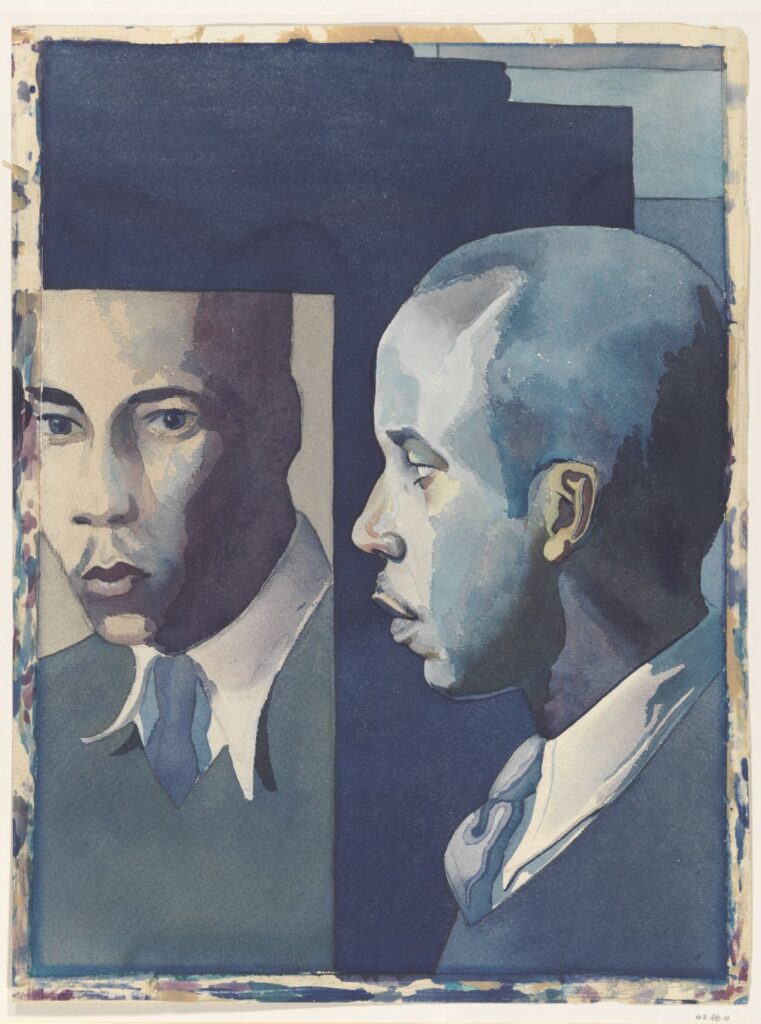

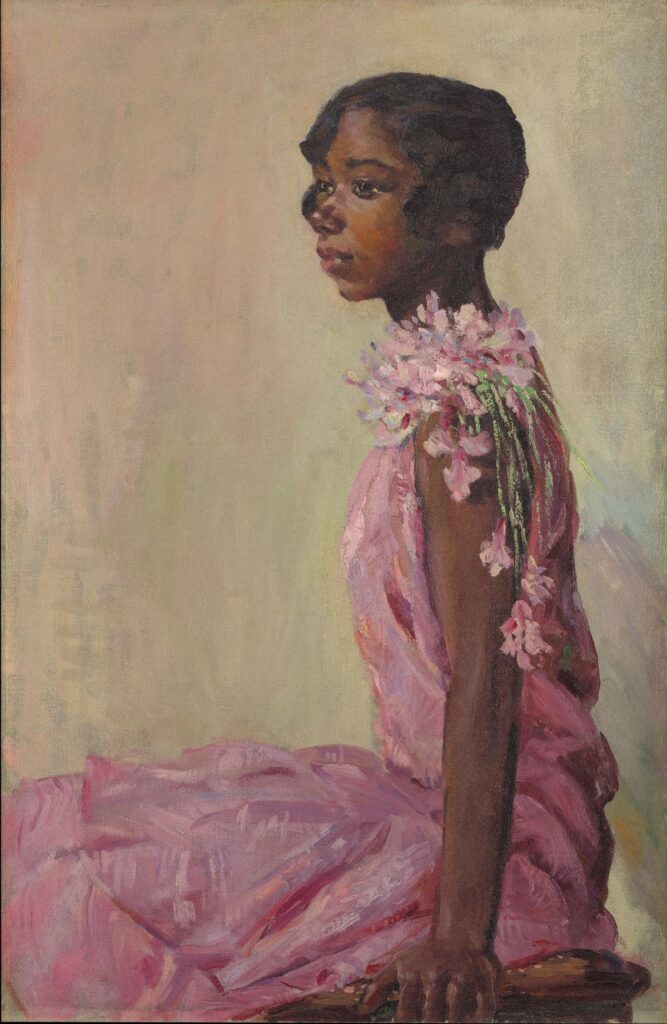

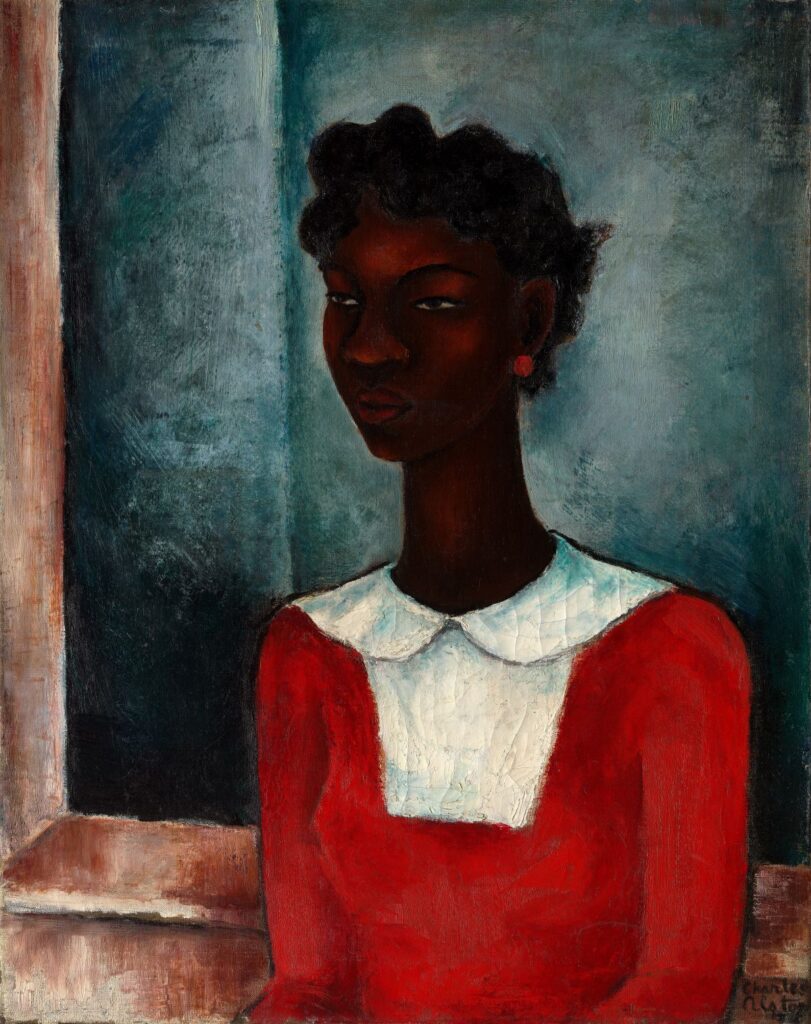

Harlem, of course, was the great cultural Mecca to which African Americans were drawn in the course of the so-called Great Migration, when, beginning in the early years of the twentieth century, they moved north from the southern United States to such cities as Chicago, Detroit, and, most of all, New York. Ezra Pound once wrote something to the effect that all it takes is five hundred gifted and committed people to found a civilization, and that seems to be borne out in the present context. In an area of scarcely one and a half square miles, an astonishing explosion of creativity occurred, not only in the visual arts, the focus of the present exhibition, but also in literature, music, and dance. Even more extraordinary is the fact that all that activity occurred in a period of scarcely twenty years, from the 1920s to a little beyond the outbreak of the Second World War. In addition to the writers Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen and the performing artists Paul Robeson and Duke Ellington, it included such visual artists as Charles Alston, Laura Wheeler Waring, Norman Lewis, and James Van Der Zee, not to mention the gifted portraitist Winold Reiss and the photographer Carl van Vechten, both of whom were white.

The Metropolitan Museum’s decision to consider this work within the context of international modernism seems accurate as far as that goes, but not as illuminating as perhaps one might wish. Because Black artists in America, no less than their white counterparts, still looked to Europe for models—as they would continue to do until the end of the Second World War—it is entirely to be expected that they should have found inspiration in Picasso, Matisse, and Otto Dix, as much as in the mass of American culture, visual and otherwise, that rose up around them. Like American art in general at that time, the art of the Harlem Renaissance was a complex product of cultural pluralism, in which, mercifully, a mainstream is neither to be sought nor likely to be found.

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism • Metropolitan Museum of Art • to July 28 • metmuseum.org