Some artists strike a rich conceptual vein and stick to it for their entire careers: think Cindy Sherman and her many personae, or Louis Wain and his cats. Taking formal consistency into account, the paradigms are Bernd and Hilla Becher, who photographed the architectural variety of Europe and the United States—most notably industrial buildings—in a signature cool, gray, tightly cropped style for some fifty years. The German duo is the subject of an extensive retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first since the artists’ deaths, and the first since very early in their joint career.

The Met show isn’t one of those belated retrospectives that reveals game-changing new information about an artist’s practice. (Although with its hundred– plus objects—including lithographs, collages, sketches, and Polaroids—and a three-essay catalogue, it deepens what we already know.) But we might consider what exactly the Bechers’ work is doing at the Met. Is it art? Their contemporaries certainly thought so. Showing at Konrad Fischer Galerie in Düsseldorf and with Sonnabend Gallery in New York from the early 1970s, they were lumped together with conceptualists like Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre. The Bechers were themselves ambivalent about such labels; according to their son, Max, who helped organize the exhibition, they didn’t even really see themselves as photographers.

Bernd was born in 1931 in Siegen, Germany, about an hour east of Cologne. He grew up in the iron-rich and industrial valleys of the Siegerland. As an art student in Stuttgart, he made collages, and painted in a style suggesting Charles Sheeler, before realizing that for the verisimilitude he sought he’d better grab a camera. Hilla Wobeser was born in Potsdam in 1934, the daughter of a photographer. During her teenage years she apprenticed at a photography studio where, as Bechers expert Virginia Heckert writes in the catalogue, her instructor impressed upon her that “photography was a tool for scientific description rather than artistic expression.”

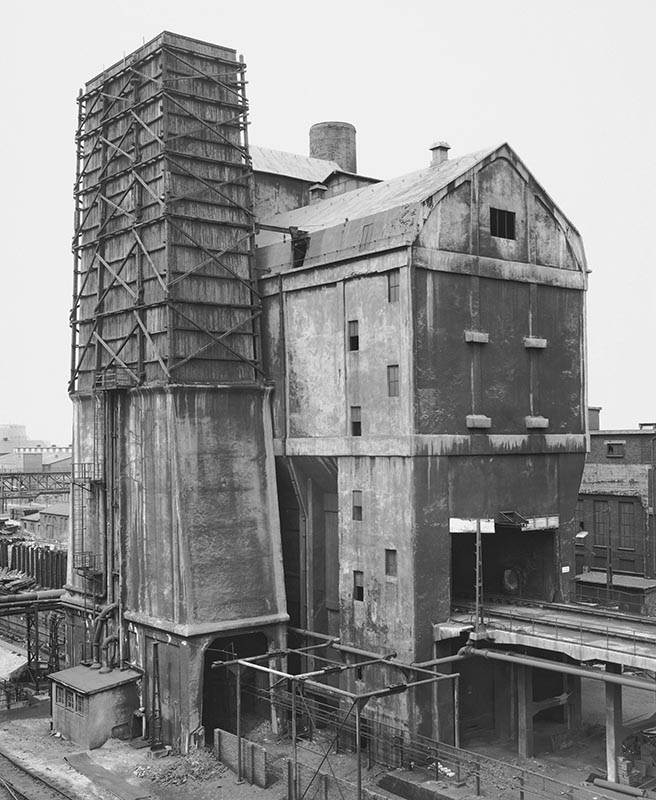

The two met while at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where in later years they would mentor some of today’s best-known contemporary photographers, including Thomas Struth, Candida Höffer, and Andreas Gursky. Bernd infected Hilla with his enthusiasm for Germany’s electrical pylons, coal breakers, lime kilns, and water towers, and the rest is history.

As anyone who’s ever operated a camera knows, the stillness of a photograph belies the painstaking nature, the “art,” of its making—whether that means getting kids to smile for a family photo, or simply making allowances for the weather. For the Bechers, the need to make pictures that appeared as if they all had been shot at the same time and under the same lighting conditions—even if, as in a superlative grouping that shows thirty blast furnaces, the project developed across decades—increased the difficulty by a power of ten.

Their approach was consistent. After identifying a suitable subject—it had to be a building type that had evolved over the course of the industrial revolution, and had to present at least one unobstructed view—the Bechers would begin the lengthy process of gaining access and surveying; lugging their unwieldy large-format field camera and suitcases of lenses through, around, and over the man-made and natural features of industrial parks; snapping the shutter up to four hundred times; and developing, printing, and editing what they’d captured. That they succeeded in the end, that their prints have an apparent sameness to them, is a triumph that barely registers in an age of digital cameras and Photoshop.

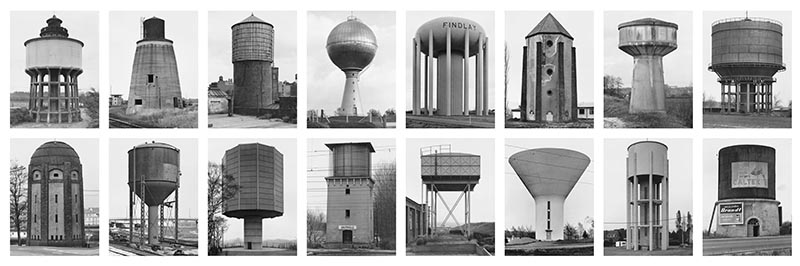

The closest parallel to the Bechers’ goals and methodology is the taxonomic work of evolutionary biologists. In fact, a copy of Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature was one of Hilla’s treasured possessions. A favorite display strategy for the Bechers was to arrange prints with systematic precision into the grids that they dubbed “typologies.” Each typology might showcase a single type of building—a gas tank, for instance, or a half-timbered house—or even different versions of a certain type of building. The viewer is invited to identify commonalities between the edifices, and to construct a mental image of the perfect form.

The Bechers’ main contention was that, photographed carefully, such “forms speak for themselves and become readable.” Which brings us back to art. Photographer Robert Adams has observed that “we take heart from form in art because in the last analysis it is a convincing metaphor for wholeness in life.” If so, it was perhaps the Bechers’ dogged, empathetic pursuit of meaning and understanding—through form—that accounts for the quiet passion of their oeuvre, and explains why it is unforgettable.

Bernd and Hilla Becher • Metropolitan Museum of Art • to November 6 • metmuseum.org