On the bumpy road to the modern world, the impressionists, their post-impressionist descendants, and those artists who came to prominence in the first decade of the twentieth century oversaw the final break with artistic tradition, and the invention of new concerns and methods that persist to this day. Telling that story is a wide-ranging exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art, The Impressionist Revolution from Monet to Matisse, which includes some ninety canvases and sculptures drawn almost entirely from the museum’s holdings.

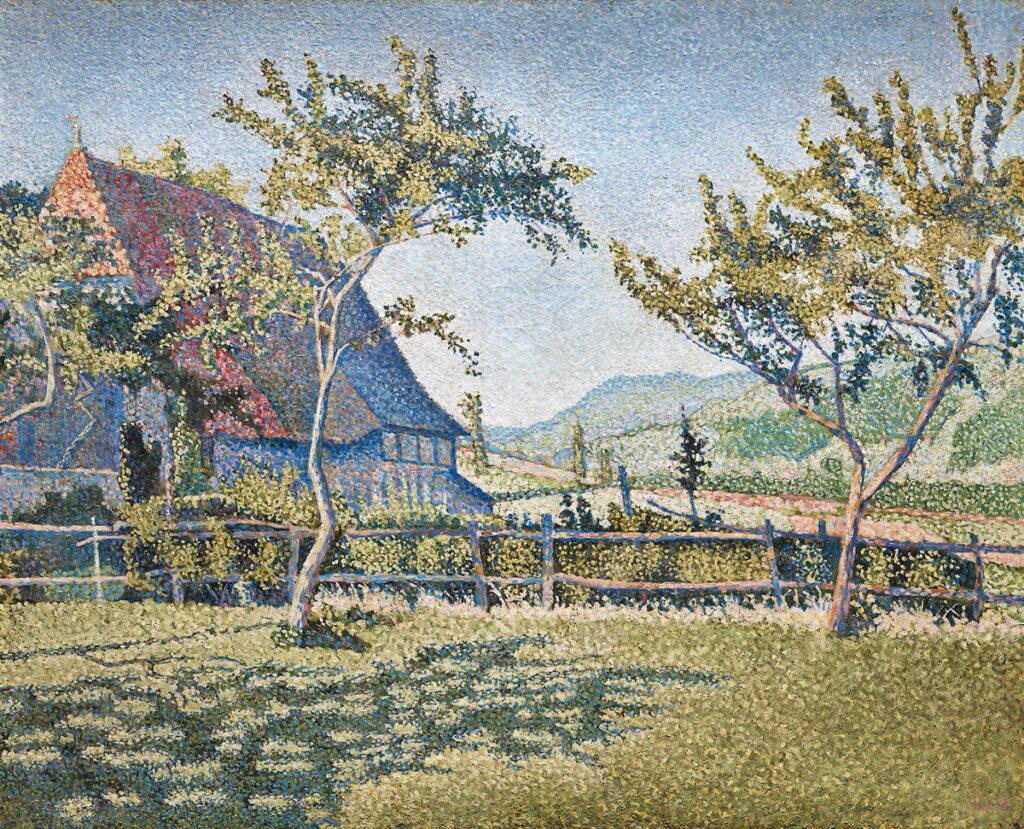

The nature of the impressionists’ innovations—seen here in conversation not only with the post-impressionists, but with the Parisian group Les Nabis, the best-known fauvists André Derain and Henri Matisse, and symbolists like Odilon Redon—was fourfold. Painters elevated the fleeting over the eternal, as is most evident in the work of Claude Monet, who insisted on finishing canvases en plein air; they relaxed the rules governing the representation of the physical world; and they established a new, more even-handed relationship between subject and background, or between what was meaningful and what wasn’t in each painted scene. And then, of course, there were those radiant, unmixed colors.

Though Manet, for example, began exhibiting his art in the 1860s, the critical response to his and others’ innovations from the entrenched establishment—which for decades had been under attack from painters of the realist school and was sent reeling (along with the rest of Paris) by the Franco-Prussian War and the Communard occupation of the capital—was swift, derisive, and persistent. It would take twenty-six years, from the first exhibition of the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. in 1874 to the inclusion of a sprawling display of canvases at the Universal Exposition of 1900, before the impressionists finally received the stamp of public and state approval.

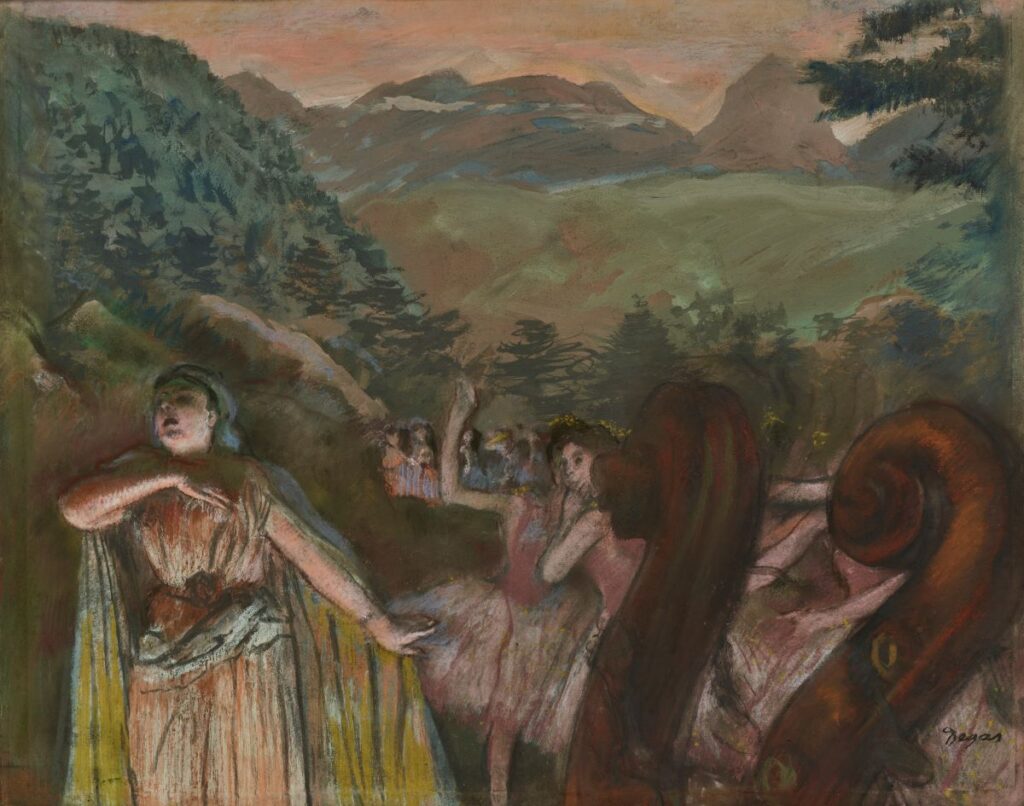

While the second and third waves of artists who followed the impressionists neither sought nor expected support through official channels, the same cannot be said for the impressionists themselves. They were almost uniformly well-to-do, some of them had been students at the École des Beaux-Arts, and when their work was occasionally selected for inclusion in the Salon they felt no qualms about skipping the impressionist exhibitions. Degas, casting a jaundiced eye on the changes he’d helped to usher in, would reflect that “two centuries ago, I would have been painting ‘Susannah Bathing,’ now I just paint ‘Woman in a Tub.’” With the termination of the Renaissance tradition, artists were now vanguards, on a lonely mission to enlighten the world from a position far in front of it.

Inc., bequest of Mrs. Eugene McDermott in honor of Nancy Hamon.

The Impressionist Revolution from Monet to Matisse • Dallas Museum of Art, Texas • to November 3 • dma.org