The painter Alma Thomas was eighty years old when she finally hit it big, receiving a small solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972—the first at that institution for a Black woman—and another exhibition later that same year at the Corcoran Gallery. Her name was made by this twilight efflorescence, but there was plenty of art packed into the eight decades that preceded it. The full story is told in a traveling retrospective now at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, which examines the long career arc of this noteworthy colorist through more than 150 objects.

Thomas was born in 1891 in Columbus, Georgia. Her mother, Amelia, was a seamstress who also painted on velvet, and it was young Thomas’s dream to be a costume designer. She enrolled at Howard University in Washington, DC, in the home-ec department, but her drawings caught the eye of artist and professor James Herring, who convinced her to enter the newly created art department. Herring also threw open the doors of his personal art library to Thomas. Her work from this period, such as an untitled still life from the early 1920s in the show, evokes Cézanne, but with a twist—the shockingly bright pastel colors that became her calling card. As she would tell the New York Times in 1972, “color for me is life.”

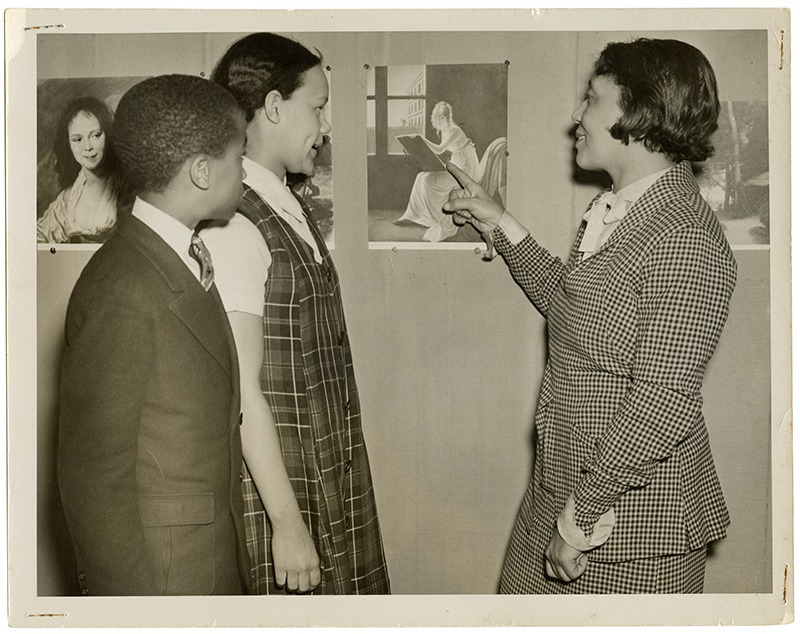

Settling in the capital’s Logan Circle neighborhood after graduation, Thomas found multiple avenues for engaging with the art and people of her community. She instructed generations of art students at Shaw Junior High School from 1925 to 1960, sometimes with the aid of marionettes that she fabricated herself, such as a clown of about 1935 with painted wooden shoes and face, clothed in bright orange and blue. In 1946 she became a member of the Little Paris Studio, a group of artists-teachers that met in the home of painter Loïs Mailou Jones, who’d spent time at the Académie Julian in Paris; from 1943 Thomas was vice-president as well as an exhibiting artist at Barnett Aden Gallery, one of the first art galleries in the United States owned by African Americans.

It was there that Thomas first noticed—and was noticed by—artists who would become known as the Washington Color School. In answer to New York’s abstract expressionist movement, in the 1950s members of this informal “school” began emphasizing optical effects over form and gesture, and became early adopters of acrylic paint. Notables such as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland were frequent visitors to Barnett Aden—which was the DC destination for artists interested in modern art currents from around the world— where they encountered Thomas and even exhibited with her, beginning in the mid-1950s.

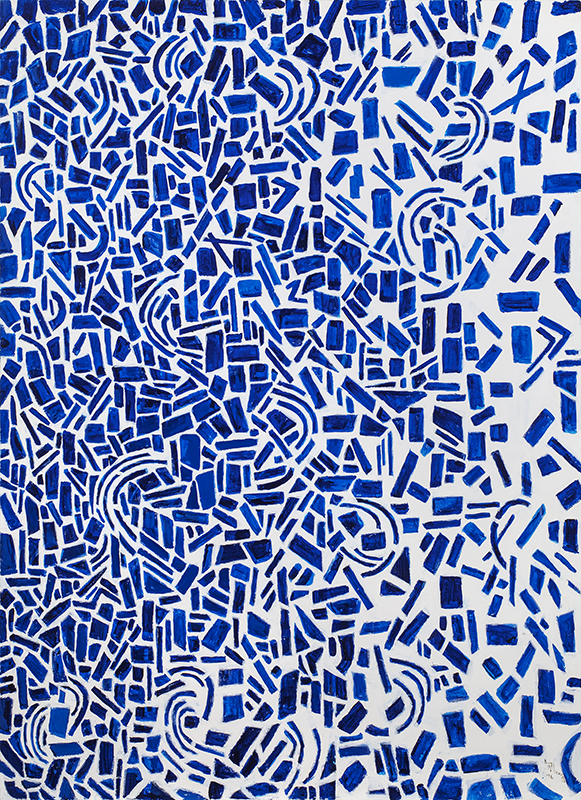

While taking graduate classes at American University between 1952 and 1957, Thomas herself converted to abstraction, and after her retirement from teaching in 1960 soon derived the mosaic-patterned style that marks her best-known work: the Earth series, inspired by the capital’s municipal plantings, and the Space or Snoopy series, whose shimmering, angular shapes evoke the NASA rocket launches of the time.

But lumping Thomas in with Noland, Louis, Gene Davis, and others of the Washington Color School, as has been done, might be doing her an injustice, at least according to Seth Feman, co-curator of the Chrysler’s exhibition along with Jonathan Frederick Walz of the Columbus Museum in Georgia. (The show will go on view at the Columbus Museum after stops at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC and the Frist Art Museum in Nashville.) “Her handling of paint is worlds apart. Her paintings are hard-edged; [the work of the Washington Color School painters] is insistently flat while she built up paint layer after layer.” That last item doesn’t translate well via print—all the more reason to see the paintings in person.

Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful • Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia • to October 3 • chrysler.org