Along with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston—which each had planned gala commemorations to mark the 150th anniversary of their founding—count Colonial Williamsburg among the cultural institutions that had to settle for much more muted celebrations this year thanks to the coronavirus pandemic. In Virginia, the festivities were to focus on a new expansion to Colonial Williamsburg’s two art museums—the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum (AARFAM) and the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. A three-year, nearly $42 million renovation added some sixty-five thousand square feet to the museums, augmenting exhibition spaces by 25 percent (encompassing seven new galleries) and supplementing visitor amenities to include wireless technology for interactive displays as well as expanding the museum café and store. While Colonial Williamsburg is open to visitors, capacity is limited in indoor spaces, and social distancing and face masks are required.

Bear with these minimal constraints, for there is much to see at the art museums. The work of one of the most beloved early American folk painters is on view at AARFAM—Edward Hicks of Pennsylvania. Trained as a decorative painter of coach bodies and trade signs, Hicks turned to making art after his conversion to Quakerism. Subject to suspicions of his own and of fellow members of the Society of Friends that his art was gaudy and superfluous, Hicks tried to impart a moral lesson in all he painted. He is best known for his many renditions of the Peaceable Kingdom—a prelapsarian world of innocence where the lion lies down with the ox and lamb, and children cavort among them.

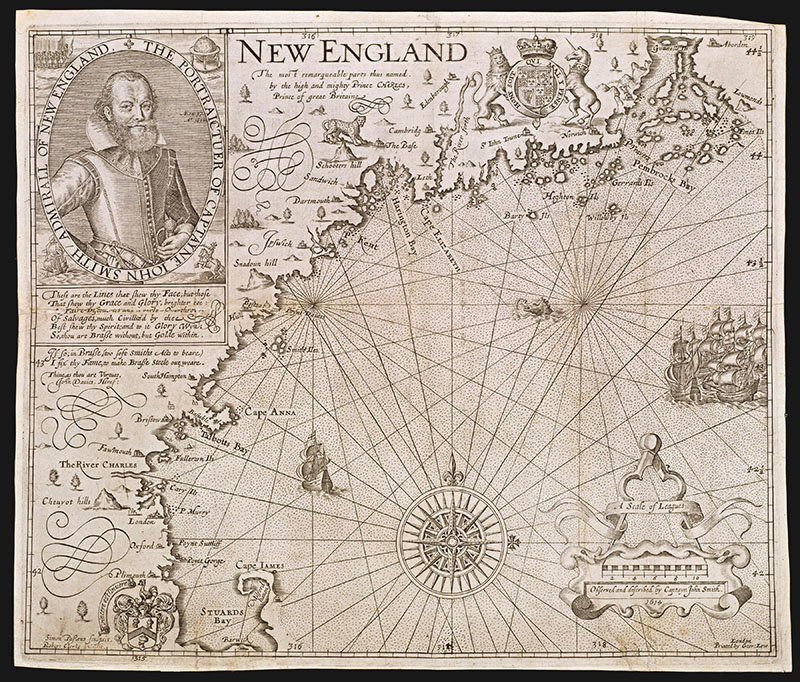

“NEW ENGLAND” by John Smith (1560–1631), cartographer, Williams Hold, engraver, and George Low and Robert Clerke, publishers, London, 1624 (originally published in 1616).

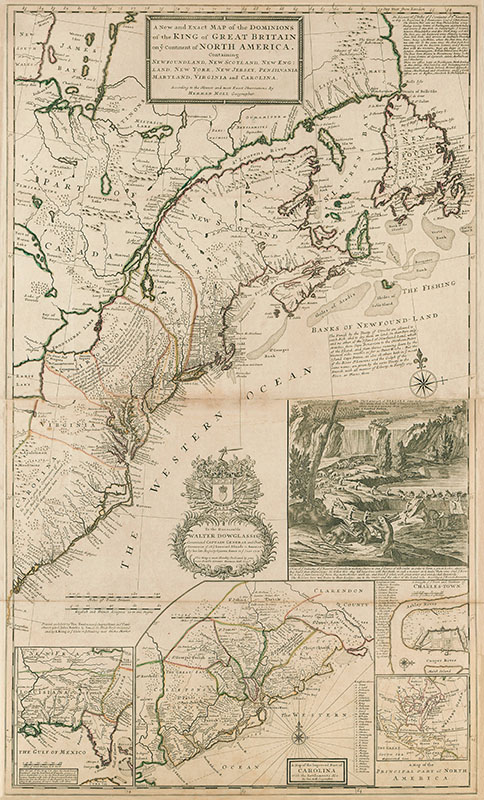

“A New and Exact MAP of the DOMINIONS of the KING of GREAT BRITAIN on ye Continent of NORTH AMERICA” by Herman Moll (c. 1654–1732), cartographer and engraver, and Thomas Bowles II, John Bowles and Son, and John King, publishers, London, after 1735 (originally published in 1715).

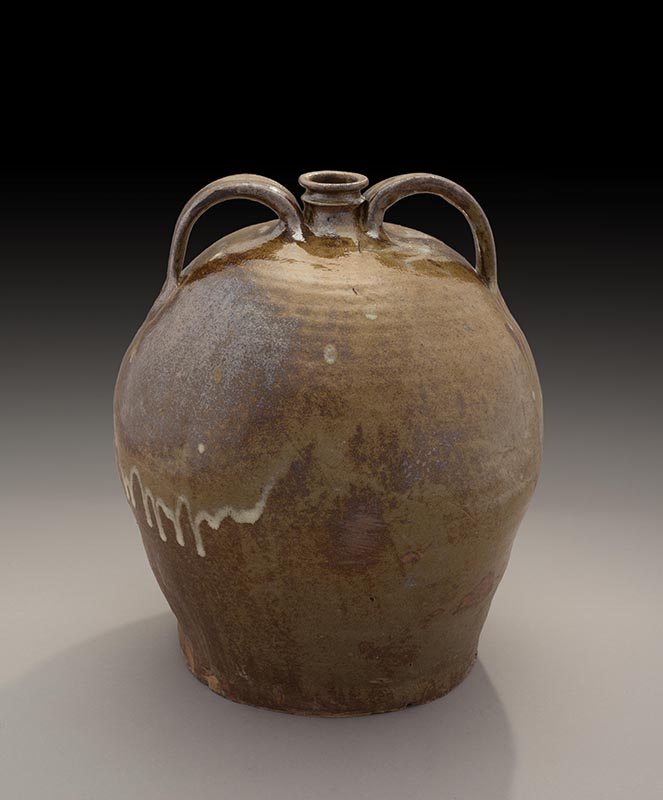

Another exhibition at AARFAM showcases some fifty examples of American folk pottery dating from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The pots come from across the United States and exemplify regional ceramic-making traditions, including those of German communities, the enslaved potters of the Edgefield District in South Carolina, and the Pueblo people of New Mexico.

Portraiture takes center stage at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. The exhibition Early American Faces demonstrates that demographic diversity was a keynote of the nation from the beginning. The show features portraits of men, women, and children; of statesmen—most notably Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of George Washington at the Battle of Princeton—merchants, farmers, and the enslaved; of Native Americans and European immigrants. The Virginia-British Connection: British Paintings with Virginia Ties is another current portraiture show at the Wallace Museum. It points up the close ties that the colony maintained with its mother country—and, not incidentally, offers a means to display the British art that Colonial Williamsburg has collected from its earliest years. That exhibition is a companion of sorts to British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg, a show that opened at the Wallace Museum shortly before the museums closed because of the pandemic. (We wrote about British Masterworks in the March/April issue of our magazine.)

The premise of an exhibition that opened in October, Promoting America: Maps of the Colonies and the New Nation, is that the early maps of North America not only provided geographical information, but also served as marketing devices and even tools of propaganda. A map of the New England coastline by Captain John Smith, published in 1616, was meant to attract participation in his proposed colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts. The map features an impressive portrait of Smith, presenting him as a sturdy, steady, and valiant man of discovery. A map of the American colonies by cartographer Herman Moll, first published in 1715, includes an illustration of the “Industry of ye Beavers” building dams. More than a lure to would-be fur traders, the illustration suggests that, in the New World, even nature sympathizes with the orderly settlement of the wilderness.

Last, an exhibition scheduled to open at the Wallace Museum in mid-November examines one of the most beautiful marriages of art and science. Keeping Time: Tall Case Clocks features nearly thirty such timekeeping devices, made both in England and in different American regions, all dating from 1700 to 1820. Tallcase clocks were, of course, the exclusive province of the wealthy of early America. Case forms followed furniture fashion trends, and customers could order special mechanical features—which Williamsburg furniture curator Tara Chicirda likes to compare to apps on today’s smartphones—to tell the day of the month, the phase of the moon, and the time of the local high tide. But for all the sophistication of the timepieces in the exhibition, the one that caught our eye was perhaps the humblest, its yellow pine case decorated in 1800 by Johannes Spitler of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia with images of hearts, birds, and a prancing deer.

The Art of Edward Hicks to December 31, 2022. • American Folk Pottery: Art and Tradition to December 31, 2022. • Early American Faces to December 31, 2022. • The Virginia-British Connection: British Paintings with Virginia Ties to December 31, 2022. • Promoting America: Maps of the Colonies and the New Republic to March 27, 2022. • Keeping Time: Tall Case Clocks November 14, 2020 to December 31, 2022. • Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, VA cwf.org