The German artist Käthe Kollwitz was born in Prussia at the moment when Bismarck was beginning the series of campaigns that would bring Europe to its knees; she would die near burned-out Dresden little more than a week before Hitler breathed his last, but not before she’d lost a son, a grandson, and her own house, and with it much of her work. She is the subject of an exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, which opened this week.

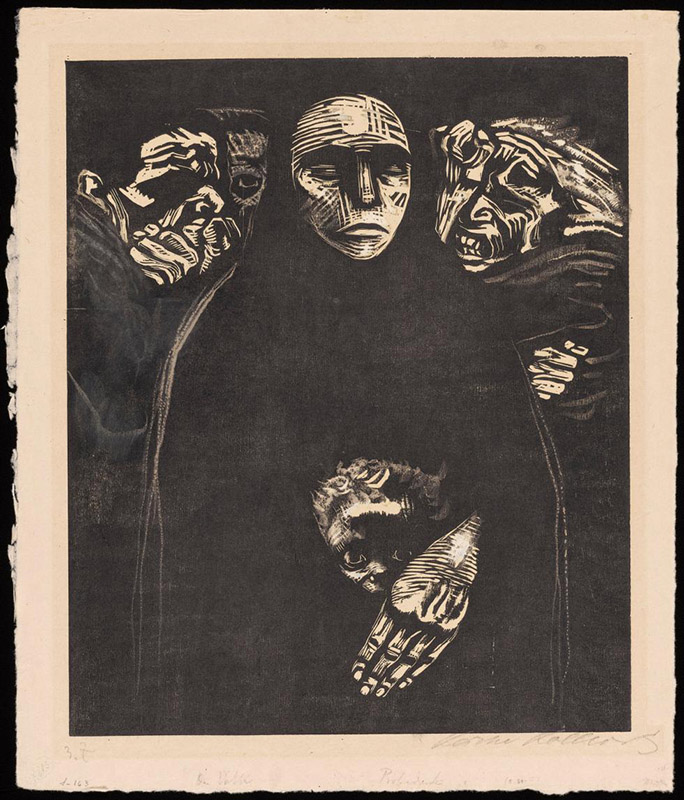

One wishes that, if only for the sake of her trifecta of artistic gifts—a keen eye, steady hand, and an emotional honesty that grabs viewers by the viscera—happier days had been hers to depict. Alas, violence, terror, and despair—in stark black-and-white detail—stare out of picture after picture with names like Hunger, Battlefield, and In Memoriam . . . And though she was raised by a family of socialists, for her, there seems to be no reassuringly simple dichotomy between oppressors and oppressed, and no guarantee of a brighter future on the other side of struggle. The faces in the crowd in Charge, a sheet from her epic etching series Peasants’ War, which depicts a sixteenth century class uprising, are like those of frenzied animals—all starting eyes and gnashing teeth. Whatever the outcome of the battle, they’ve already lost the fight against their passions, and there’s a special place in Hell reserved for people with that misfortune.

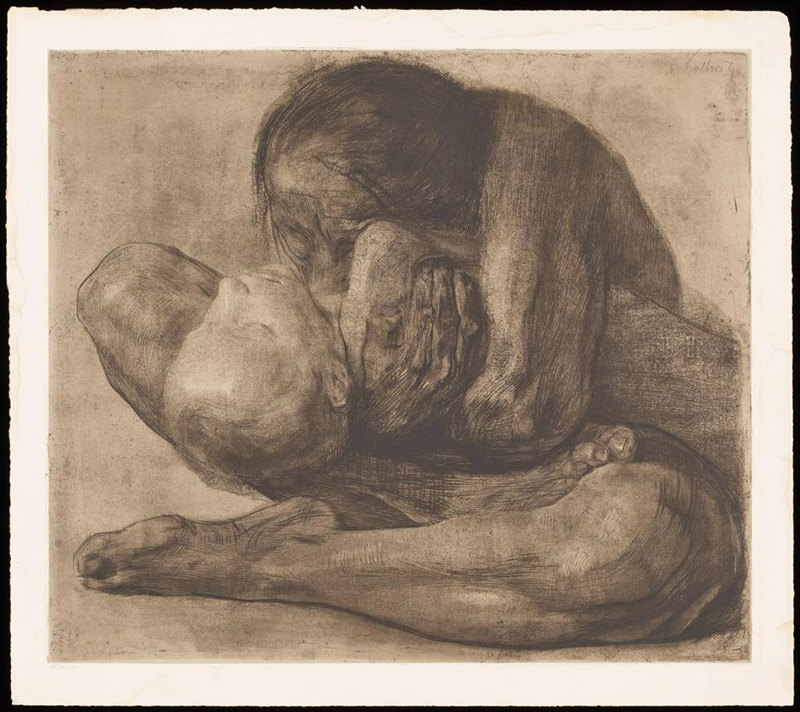

In the most devastating work on view, a bereaved woman clutches the dead body of her child. The scene is etched in vigorous, swirling lines, which seem carved like self-harm marks into the paper. You can picture the artist obsessing over the cognitive puzzle that is death, lovingly massaging a scene that’s veritably unthinkable, veritably impossible to depict, except maybe by war photographers and religious devotees (but then, in a very different way). Not one but two versions of this piece, a drawing as well as an etching, are on view at the Getty. And when she completed them, in 1903, Kollwitz had not even lost a child of her own yet. “Everywhere beneath the surface are tears and bleeding wounds,” Kollwitz wrote to her remaining son, near the end of the Great War. “And yet the war goes on and cannot stop. It follows other laws.”