By Ruth Davidson; Originally published in January 1971

For the enchantment of visitors to Asia House Gallery this month and next there will be on view byōbu, or Japanese painted screens, from twelve museums and private collections in New York. Arranged so as to suggest their appearance in a Japanese house, the twenty six screens will be shown in two groups, the first from January 14 through February 14 and the second from February 16 through March 14. (The address of Asia House is 112 East 64th street, New York, 10021).

Byōbu, decorative and useful pieces of household equipment that are at once art objects, like the framed pictures that hang on the walls of fine houses here, and architectural components that serve as temporary walls or partitions, make a direct appeal to Western eyes. Their clear and compelling design, their brilliant or, again, subtle and low keyed color schemes, and the poetry of their subjects can all be appreciated without one’s knowing anything about the history of screens or their relation to other forms of Oriental art. But the interest of these works increases as we learn about the various identified screen painters, their techniques, and the artistic traditions they upheld. The catalogue of the Asia House exhibition, prepared by Professor Miyeko Murase of Columbia University, who also chose the examples to be included, makes an excellent introduction. With a compact, scholarly, and readable text and detailed descriptions of all the screens, it is in fact the only brief, comprehensive account of Japanese screens in English to be recommended. (A large and sumptuously illustrated volume manufactured in Japan has appeared since Miss Murase completed her work: The Japanese Screen, by Elise Grilli, New York, 1970.)

Ancient scroll paintings and literary documents prove that screens were made and used in Japan almost from the beginning of the country’s history. The portable folding screens called byōbu had their remote origin in China under the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-221 A.D.) but it was in Japan that their aesthetic potentialities were fully realized. In 686 a byōbu was received as a gift at the Japanese court, and by the middle of the eighth century such screens were in common use in the houses of noblemen as well as in the imperial palace. One rare set of screens of this time is preserved at Nara, the ancient capital of Japan, near Osaka; together with a later (eleventh-century) example known as the Senzui byōbu, now in the Kyoto National Museum, it exemplifies the oldest method of construction, in which several panels of the screen, each surrounded by a border of silk or wood, were joined by silk or leather cords. In the mid-1300’s a new way, still in use, of joining the panels was found: by wrapping long strips of paper across the front of one panel and the back of the next, and then repeating the procedure in the opposite direction, thus forming an invisible hinge. The change made it possible to do away with the old borders and to mount the panels on frames of which the edges are visible only at top and bottom and on the outer sides of the end panels. The technical advance contributed to the development of a unified decorative scheme, since the several panels could now be treated as one.

Fig . 3. Irises and Bridge, one of a pair of six-fold screens painted on paper by Ogata Kōrin (1658-1716); Edo period. Height 70 ½ inches. A zigzag footbridge, cutting diagonally across the panels of the two screens, is bordered by clumps of irises with deep violet-blue flowers, gray-blue under-petals, and stalks and leaves of brilliant clear green. Even now, softened by time, the colors glow against the diapered gold background that catches the light in broken patterns. Kōrin, the painter of these famous screens, was the best known of a school or group of decorative painters that come into prominence in the early seventeenth century. His life, full of dramatic episodes, successes, and disappointments, is well documented by his papers and letters, carefully preserved in his prosperous, cultural merchant family. Metropolitan Museum of Art: Louisa E. McBurney gift fund.

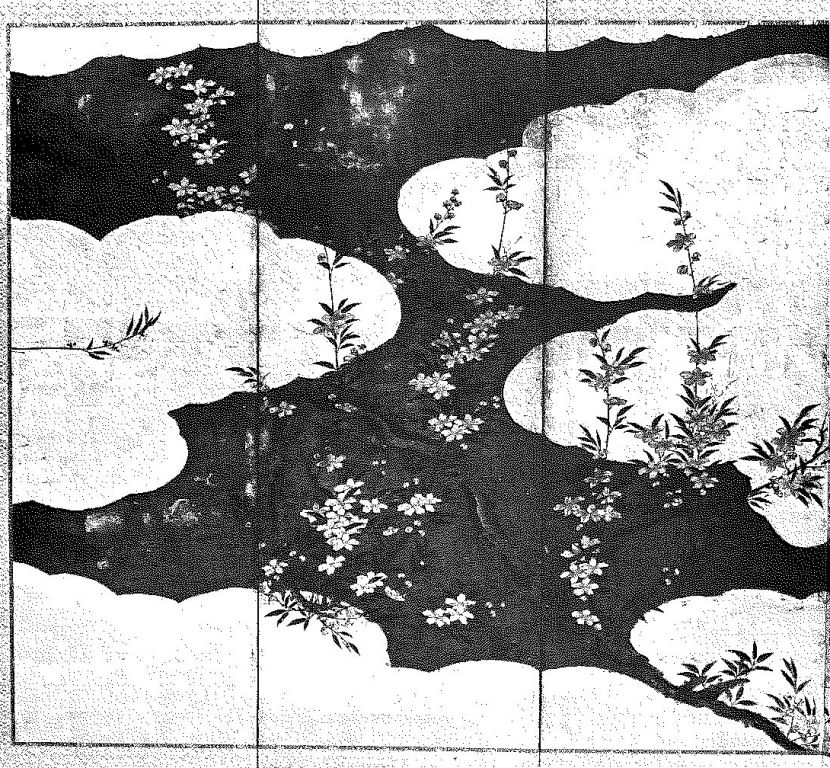

The precious and fragile early byōbu still to be seen in Japan today–and, on such rare occasions as the Asia House exhibition, in the Western world–were made from the late sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries. By this time a distinctive Japanese style had emerged in all the arts, including–as literary references and representations in scroll paintings indicate–the decoration of screens. In this style, called Yamato or Japanese painting, such subjects as Japanese scenery, poetry and stories of old Japan, and ceremonies marking the passage of the seasons were depicted in bright flat colors. In contrast to the lively Yamato decorative schemes was a more subdued, poetic type of painting in monochrome ink that had been introduced to china in the wake of Zen Buddhism. Idealized landscapes, often including views of celebrated sites in China or the personages of Chinese history and legend–scenes conducive to meditation and scholarly detachment–were rendered in this technique for the decoration of Zen monasteries and later, the homes of noblemen. Ink-painted screens of the later Muromachi period (1336-1573) survive in some numbers and the Asia House exhibition includes examples by Sōami (Fig. 4) and Motonobu (1476-1559).

The general composition of certain landscape paintings of this time, notably the work of the great landscape painter Shūbun, was to become standard in succeeding periods. The large picture space obtained by combining two screens with their several panels invisibly hinged was divided into three well-defined areas, one at the extreme right, one at the left, and the third occupying the adjoining halves of the two screens. In the right- and left-hand sections the various elements of the landscape are depicted as if seen at close range, while the central part of the scene is represented from a more distant viewpoint. (Like Oriental writing, such pictures are “read” from right to left.) This framework lends itself admirably to representation of the four seasons–one of the great themes of Japanese art of all epochs–or to subjects like the four accomplishments of a cultured man.

Fig. 4. Landscapes of Four Seasons, detail from one of a pair of six-fold screens decorated in ink on paper by Sōami (d. 1525); Muromachi period. Height 68 ¼ inches. The idealized landscape, an example of the technique of ink painting that combines soft, slightly blurred strokes and light washes, expresses the vision of a serene and noble Nature held by the Zen monks–and all the ink painters–of the time. It may have been Sōami, a member of a Buddhist sect that included many artists and artisans, who popularized this style of painting; the author of influential books on artists and decoration, he was a “taste maker” as well as one of the greatest artists of this early period. Metropolitan Museum of Art: gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Fig. 5. Landscape in Mi Style, one of a pair of six-fold screens painted in ink on paper by Yosa Buson (1716-1783); Edo period. Height 57 1/8 inches. The foliage of the trees, the low, thick growth of shrubs, and the shore line that defines the foreground in this view are rendered in the short, dotlike, horizontal strokes that characterize the Mi style (so called after Mi Fei, 1051-1107, the supposed inventor of this pointillistic technique). Buson was first famous for his haiku or short poems of a type that originated in the 1600’s. Turning to painting in his late thirties, he became one of the two greatest Nanga painters of Japan, who strove to grasp the principles of nature and of painting through travel and the study of the Chinese classics. Collection of Robert Ellsworth.

Apparently some of Shūbun’s contemporaries found the delicately nuanced but often somber ink paintings, which enjoyed the highest esteem at the time, somewhat unsatisfactory as decorations for screens. In the work of another–perhaps the greatest– landscape painter of this time, Sesshū (1420-1506), decorative quality was restored by the use of stronger, more emphatic brush strokes, the organization of the pictorial elements, and the successful introduction of color. The trend was continued in the work of Masanobu (c. 1434-c. 1530), chief court painter to the shogun, or military commander, of his day, and that of his son Motonobu. According to tradition, Masanobu was the founder of the Kanō school which dominated Japanese painting for almost two centuries (Kanō is a family name, adopted, if not inherited, by the leading proponents of this style).

The Momoyama period (1573-1614) may be called the golden age of painted screens for more reasons than once. Not only were works of the highest quality and most varied subject matter produced but actual gold was liberally used in their decoration. Gold leaf applied in large squares to the entire surface made the striking gold-ground screens of which the Metropolitan Museum’s Irises and Bridge (Fig. 3) is a famous example; small flakes of gold were sprinkled over painted areas; and gilt was used along with ink and colored paints. Already in demand by the mid-1400’s, when they were used both in temples and in homes, the gold screens were even more popular in the succeeding century, when fortified castles were being built in many parts of Japan as a defense against firearms, which came into Japan in 1543. The growing might and wealth of the war lords found an appropriate symbol in these splendid creations, which shone from the darkest corners of large audience halls in the daytime and reflected the light of hundreds of candles at night.

Fig. 7. Autumn Millet, detail from one of a pair of eight-fold screens in color on gilded paper attributed to Kanō Sanraku (1559-1635); Edo period. Height 38 ¾ inches. The rich, ripe heads and twisted leaves of the familiar, nutritious millet plant, painted in brown are relieved by sprays of wild aster and, here and there, a bit of ragwort “bursting into a tiny candelabrum of gossamer seed” (Alan Priest). Small birds– finch, sparrows, and quail?–flutter overhead in spite of the rattles, hung from ropes, that are meant to scare them away. These unusually short screens had always been in private collections in Japan; the Kanō painters worked not only for palaces and temples, but for the households of the rich as well. Metropolitan Museum of Art; Pulitzer bequest.

Fig. 7. Autumn Millet, detail from one of a pair of eight-fold screens in color on gilded paper attributed to Kanō Sanraku (1559-1635); Edo period. Height 38 ¾ inches. The rich, ripe heads and twisted leaves of the familiar, nutritious millet plant, painted in brown are relieved by sprays of wild aster and, here and there, a bit of ragwort “bursting into a tiny candelabrum of gossamer seed” (Alan Priest). Small birds– finch, sparrows, and quail?–flutter overhead in spite of the rattles, hung from ropes, that are meant to scare them away. These unusually short screens had always been in private collections in Japan; the Kanō painters worked not only for palaces and temples, but for the households of the rich as well. Metropolitan Museum of Art; Pulitzer bequest.

The Kanō painters and in fact most artists of this time decorated screens for temples, castles, palaces, and the houses of the wealthy in various styles. Using now ink, with the meticulous technique this medium imposes, and now brilliant colors in highly abstract designs, they treated the whole range of traditional subjects–historical, narrative, landscape, and genre. The young Kanō Eitoku (1543-1590), a grandson of Motonobu, for example, who was employed by the shogun Hideyoshi on the interior decoration of Nijo castle, a great walled and moated pile in Kyoto, is best remembered for his paintings of lions, hawks, and trees on a heroic scale. He also executed genre scenes, and his screens based on the Tale of Genji illustrate a classic of Japanese literature.

The screen painters of the succeeding, Edo period (1615-1867) continued to work in all the fields cultivated by their Momoyama predecessors. The names of numerous Edo painters are known, and their works well identified and classified. Sōtatsu and his followers–among them the great designer Ogata Kōrin (Fig. 3)–revitalized the old Yamato tradition; their works, often inspired by literary themes, have in common great beauty and an abstract quality that is highly effective. Nanga (Southern school painting), also known in Japan as Bunjinga, was inspired by the Chinese gentlemen painters of the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties. Yosa Buson’s Landscape in Mi Style (Fig. 5) is an example of Nanga work, of which a characteristic is the use of ink as the primary medium with–occasionally–light washes of color. Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) strove to represent nature objectively, from direct observation; Matsumura Goshun (Fig. 6) and the animal painter Sosen (1757-1821) were among his followers. Anonymous decorators of screens, forming a large class apart, are known as Machieshi, or town painters. Produced for the public of wealthy merchants and others who enjoyed genre scenes–viewing the cherry blossoms, the horse races, the archery contests, the Kabuki and Noh theaters, and the houses and beautiful women of the pleasure districts–their work gives a lively picture of urban life in a Japan as yet little modified by foreign influences.