A view of the reception hall of Reynolda House takes in artwork that includes, on the second floor, from left, Sierra Nevada by Albert Bierstadt, 1871–1873, and In the Studio by William Merritt Chase, c. 1884, and, on the ground floor, Home in the Woods by Thomas Cole, 1847. All images courtesy of Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

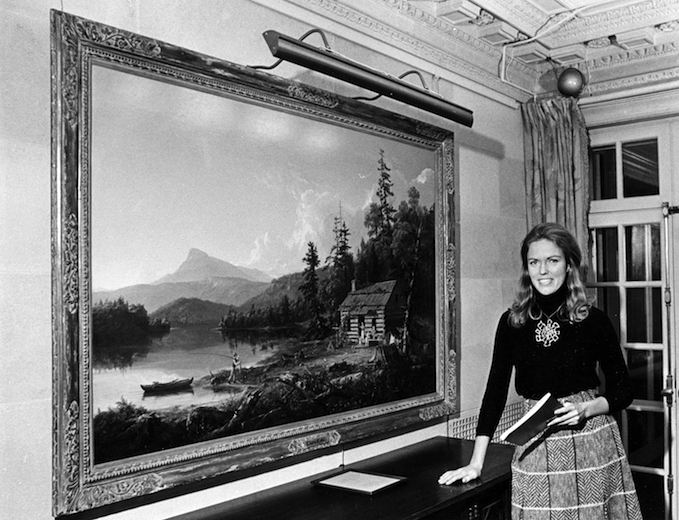

Barbara Babcock Millhouse.

One hundred years ago, Reynolda House—the sixty-four-room centerpiece of the 1,067-acre estate of tobacco magnate R. J. Reynolds on the outskirts of Winston-Salem, North Carolina—welcomed its first guests. Exactly fifty years later, Reynolda House opened its doors as an art museum, one with an exclusive focus on American painting, sculpture, and works on paper. Both projects—mansion and museum—were the work of women.

Katharine Smith Reynolds (1880–1924), R. J.’s wife, worked hand-in-hand with Philadelphia architect Charles Barton Keen to design the house. Described as an arts and crafts bungalow, the building’s unostentatious, low-slung profile and white stucco walls impart an easygoing warmth. The interior presents a more formal symmetry in a colonial revival center-hall plan. Katharine Reynolds and Keen chose furnishings from John Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia in a mix of historical revival styles, from Tudor and Louis XV to Italian Renaissance and Adamesque, to give the rooms a variety of specific looks. In all, Katharine Reynolds created a rare thing: an environment that is at once stately and cheerful.

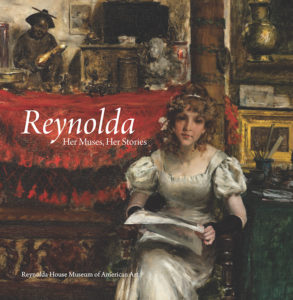

Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories is a new book about the museum.

Her granddaughter, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, made another rare thing: an art museum that is both erudite and accessible. What’s more, she made it from scratch and, if not singlehandedly, with a single-minded purpose. At its opening, the collection of the Reynolda House Museum of American Art consisted of nine canvases. They included works by Gilbert Stuart, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt, Martin Johnson Heade, and William Merritt Chase. Today, the collection has grown to nearly two hundred works that together comprise a survey of nearly every significant movement in the history of American art.

We visited Millhouse in the New York City apartment she shares with her husband, Nik Millhouse, a retired educator, to chat about the Reynolda House Museum of American Art’s past, present, and future.

The Magazine ANTIQUES: So by the mid-1960s, Reynolda was no longer a family home. Your father, Charles Babcock, had turned the estate into a nonprofit institution for the arts and education. Basically, it was open for home tours. How did you get involved?

Millhouse with Home in the Woods, soon after it was acquired in 1969.

Barbara Babcock Millhouse: It was because of a sofa. Reynolda House was being managed by an organization called the Piedmont University Center, which was supposed to make sure that the furniture looked ok because the public was coming through. A lot of people. One day, I noticed that the Piedmont University Center had reupholstered the sofa in R. J. Reynolds’s study. It was originally maroon leather and they had put on vinyl. I mean, between you and me, it was exactly the same color, but I had studied interior decorating for three years at the Parsons School of Design, and it really upset me a lot. I went to my father and said: “Look what they’ve done! They’ve put vinyl on the sofa, and I just don’t think we should let them reupholster anything more here. It’s just going to look like one big office.” And he looked at me and said, “Barbara, would you like to be president of the board of Reynolda House?” And I said: “Sure, Daddy.”

Spring Turning by Grant Wood, 1936, hangs in the Reynolda House library.

Did you realize what you were getting into?

I could take care of the house. I was a decorator. I knew how to do that. Or how to get people to do it. Never did I think that I was ever going to have to give a speech, or raise money, and do all the things that running a nonprofit requires. But it was incremental, so it wasn’t ever particularly stressful.

The garden-side facade of Reynolda House.

How did the Reynolda art collection come about?

I had done two or three little art exhibitions at the house. The idea of putting together a permanent collection sort of grew out of those borrowed paintings that we were showing at that time. I realized that you couldn’t really get good paintings by borrowing them. And then Stuart Feld showed up.

Our readers will know Stuart Feld as the head of the New York gallery Hirschl & Adler, but at that time he was a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stuart gave the most wonderful talk on John Singleton Copley. (There was a Copley show on at the National Gallery of Art in the fall of 1965.) I was an art history major at Smith, and we were taught to think that American art was second-rate, and I just remember watching the slides Stuart presented and thinking: these are fantastic paintings; why didn’t anyone tell me? You know, it was really kind of an epiphany. I suddenly saw what American art was all about.

Stuart and I went and talked after the lecture for about an hour. I don’t think it was any longer than that. And I’ve asked him if he remembers what he told me that time. And, of course, he doesn’t remember. But I’m sure I said we really want to start a collection at Reynolda, and I’m sure he said, “You should look at American art, do American.”

Frederic Edwin Church’s The Andes of Ecuador, 1855 on display in the reception hall.

As I understand it, you convinced the Reynolda board to start a collection, then persuaded the director of the Met, Thomas Hoving, to allow Stuart Feld to serve as your adviser.

Yes. We raised $300,000 to put a collection together from family foundations and some family members by December of ’66. Apart from Stuart’s advice, I must have twenty different answers for why we chose to collect American art. But one is: with $300,000 in those days we could buy one mediocre Monet—which is what everyone wanted then—or with $300,000 we could build a collection of American art.

Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis (Sally Foster) by Gilbert Stuart, 1809. Original Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth; Ramsey photograph.

One of the first works you bought was an amazing Frederic Church landscape, The Andes of Ecuador. At that time Church and the other members of the Hudson River school had been almost forgotten.

You know, Tom Hoving spoke at our opening and he said: “People touring the house are going to be struck repeatedly by certain paintings. The names of artists, in some cases, are not going to mean much to them. The quality of the work is.” The Church certainly fit that bill. But I try to explain to people that the only thing we were trying to do was to get artists who were important historically. And even if they hadn’t become so desirable today, people would still be able to learn something about the period by studying the painting. That’s what I was looking for. The fact that Frederic Church was so significant in his own period was something to contemplate, particularly before we began to rediscover the Hudson River school paintings. Why did all those people stand in line and pay twenty-five cents to see this by Frederic Church? What did it say to them that became lost for more than sixty years?

Sierra Nevada by Albert Bierstadt, 1871–1873. Original Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth; Photograph by David Ramsey.

What changed perceptions?

When Barbara Novak’s book [American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism, and the American Experience] came out in 1969, her scholarship got others interested in the field. Critics were no help; neither were most art teachers. [New York Times critic] Hilton Kramer called Church’s paintings “simply boring.” After we hung The Andes of Ecuador at Reynolda House, somebody—[not] the only person saying something like this—looked at it and got very indignant and said: “My art teacher told me that a new painting that has detail in it is a bad painting.” So there were a couple years there when I kind of wondered, where are we going from here?

Conversation Piece by Charles Sheeler, 1952. Museum Purchase; Ramsey photograph.

It’s funny how reputations change.

Take Charles Burchfield. My sister and I both loved Burchfield’s watercolors. I always sort of felt that way about nature, anthropomorphically, certainly when I was a child. No one paid any attention to him, and his work was very inexpensive. Then a few years ago the sculptor Robert Gober curated a Burchfield show that went all around the country, and now everyone thinks he’s fabulous.

One artist I’ve always loved, and I still love, is Walter Murch. Have you heard of him? We all thought in the sixties that Walter Murch was sort of the Vermeer of American art. No one’s ever heard of him today, but I still think somebody’s going to rediscover him.

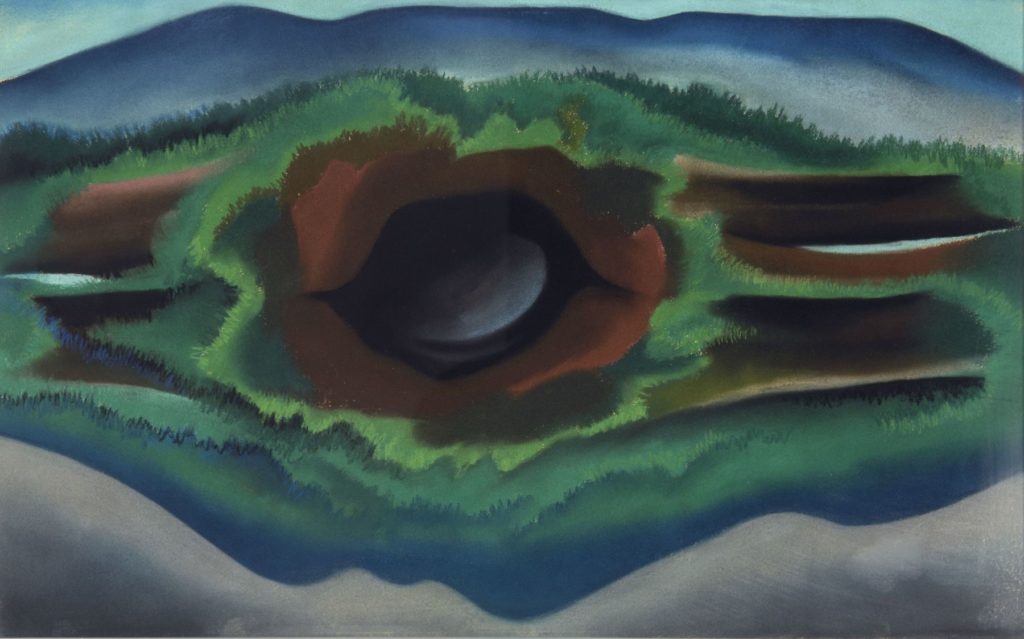

Pool in the Woods, Lake George by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1922. Gift of Barbara B. Millhouse in memory of E. Carter, Nancy Susan Reynolds, and Winifred Babcock; Ramsey photograph.

The shows Reynolda House has been presenting lately are pretty impressive. You have a Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition that traveled from the Brooklyn Museum; and next year you’ll have a Frederic Church show that’s coming from the Detroit Institute of Arts. That’s playing in the big leagues.

I asked [the museum’s executive director] Allison Perkins why they chose O’Keeffe and Church for our centennial year. She said they looked at the collection and felt that the two most iconic paintings in Reynolda are O’Keeffe’s Pool in the Woods, Lake George and the Church. It took a lot of negotiation to get those shows, but the timing was perfect and they thought it was only fitting that they have something with Church and O’Keeffe.

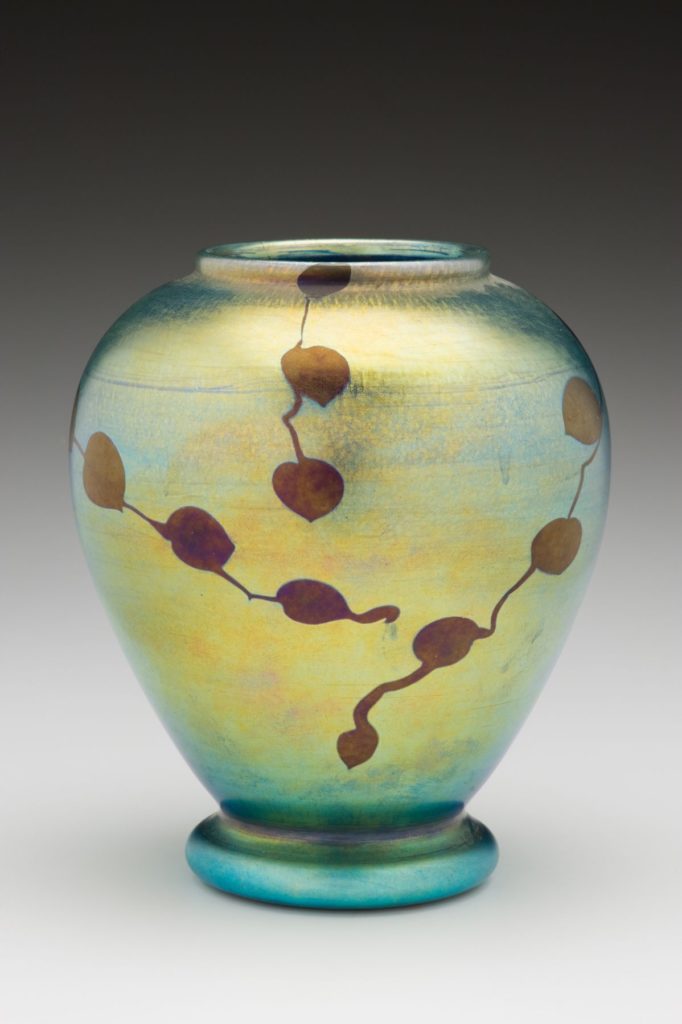

Tiffany favrile glass vase, 1910. Reynolda Estate.

Do you have any advice for art collectors?

I had been collecting for ten years before Reynolda started its collection. So I knew some of the pitfalls of the art market, particularly because I had bought some Old Masters that I might as well have thrown away, because, as it turned out, none of them were considered to be by the hand of the artist.

A Queen Anne–style settee, upholstered in blue silk damask, c. 1917. Reynolda Estate.

What I decided is that—unless you have an unlimited income—it’s better to buy a very good painting by a lesser artist than a bad painting by a great artist. So many museums buy bad paintings just because they have an important name on them. And I think it’s really curious because people will come in and they’ll look at that painting by, let’s say, Raphael. They have been taught that Raphael is a great artist, but looking at that painting they will not understand why.

Urn (& Lights) by Walter Tandy Murch, 1945. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, New York.

There’s an interesting tale behind each artwork, I imagine.

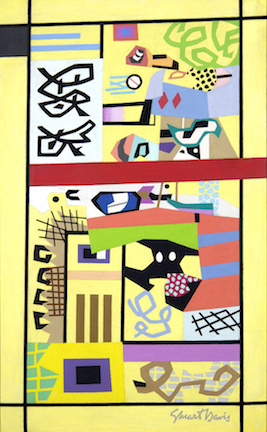

Do you know the spooky story about the Stuart Davis painting? I was at a cocktail party at an art dealer’s place in New York and for some reason I said to him that my favorite painting is Stuart Davis’s For Internal Use Only. He calls me up about two weeks later and says, “Barbara you know that painting is available. It’s for sale.” Well, it was the highest price I have ever paid for anything . . .

For Internal Use Only by Stuart Davis, 1945. Gift of Barbara B. Millhouse, Art, © Estate of Stuart Davis/Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York; Ramsey photograph.

Years later, the archivist studying the family papers telephoned and said, “Barbara you better come look. I’ve found something in your mother’s files.” And there was this Life magazine article from 1947 with a full-page color reproduction of that very Stuart Davis painting. There is no way I could have been sitting next to my mother when she was looking through Life magazine back then. You know, my mother died when I was only nineteen. She had studied art for a short time in Paris—I would think she had some interest in abstract art, probably. But who knows? It’s very weird. It gives me the heebie-jeebies.

For more memories and the backstories to other artworks in the collection, you can look to a new book published by the museum in commemoration of its 50th anniversary: Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories (264 pp.; more than 150 color and b/w illus.)