From the bullfighting ring to the atelier, Portuguese photographic pioneer Carlos Relvas constructed an early studio every bit as eccentric as his life.

5 1/8 by 7 1/8 inches. All photographs by Pieter Estersohn.

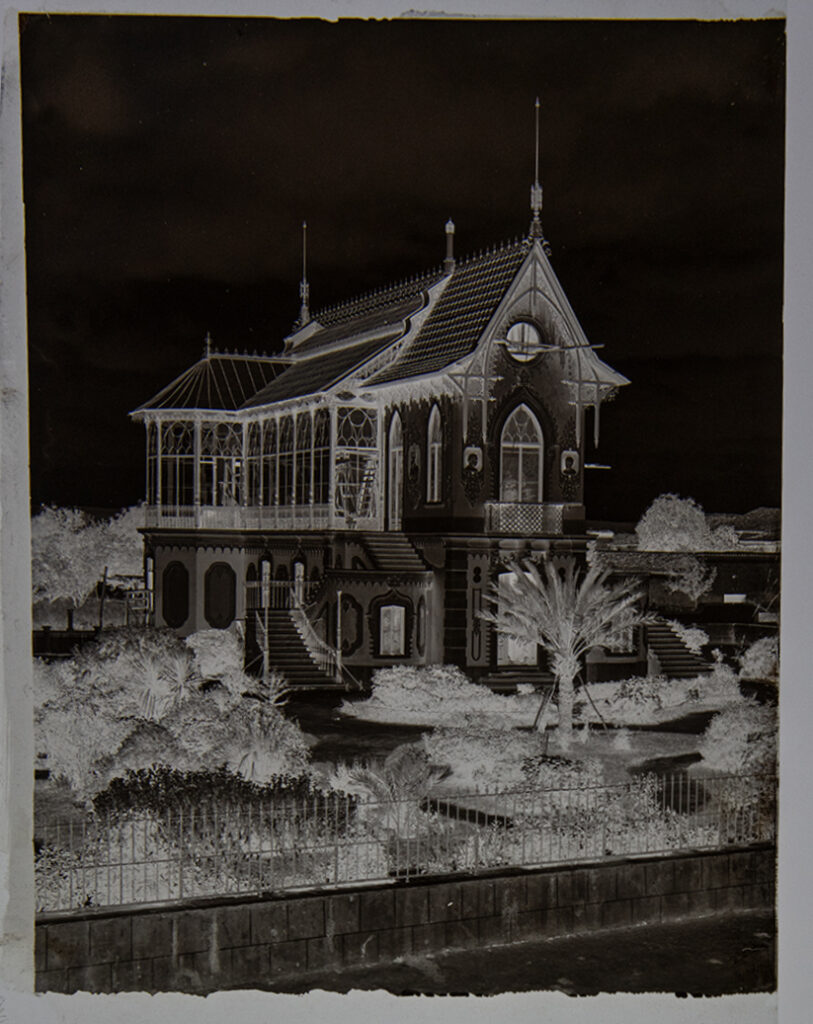

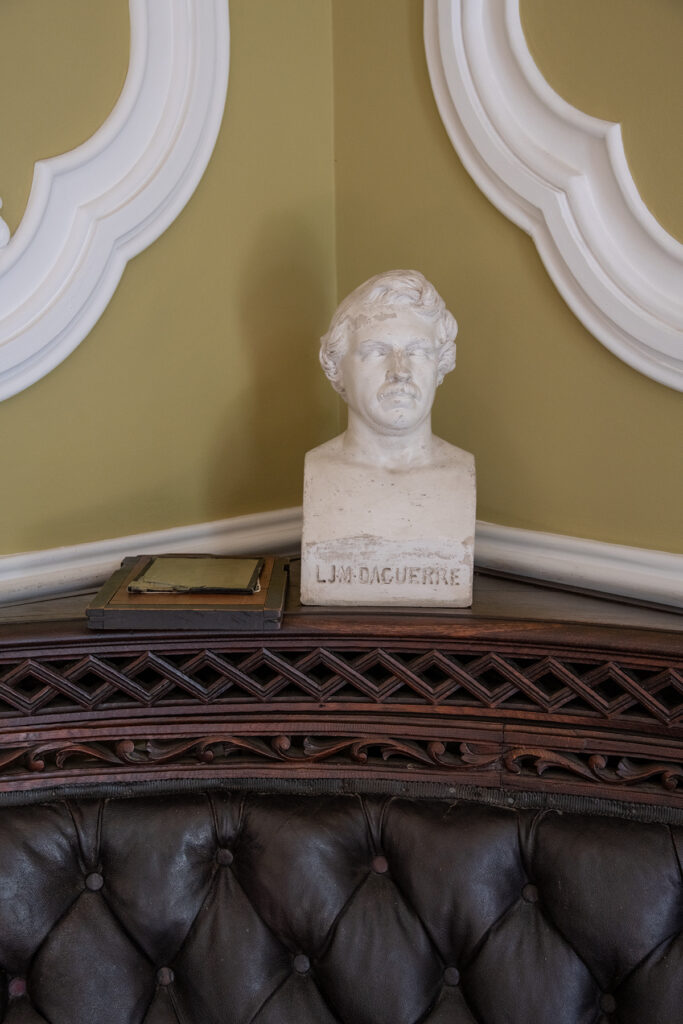

In 1872 Carlos Relvas initiated the construction of his magnificent Gothic revival photographic studio in Golegã, a small, isolated village that one can drive to in under two hours from Lisbon, passing through the rich agricultural Ribatejo region of Portugal. When I recently visited to photograph this story, the temperature was well past a hundred degrees Fahrenheit, which heightened the poetic, almost Lampedusian nineteenth-century slumber that enveloped the surrounding neighborhood. With cartoon-sized beads of sweat ejecting themselves from my body while shooting in the Grand Palais–scaled studio, I reflected on the inability of his sitters, Portugal’s Italian-born Queen Maria Pia of Savoy included, to “swing by” for a quick portrait toward the end of the nineteenth century, when lengthy and dusty carriage travel would certainly have impeded a prolific and profitable business model. Following the initial chapters of the history of the medium in the 1830s and ‘40s, photographers invariably placed their workspaces in the epicenter of capital cities in order to profit from the convenience offered to their clientele. Golegã is most definitely not in the center of anything except magnificent countryside.

Standing in front of this unprecedented Gothic cathedral of photography and eventually seeing with my own eyes the masterful negatives and prints that Relvas created there, I came to understand why royals and commoners alike made the pilgrimage, just as I was doing, to visit this very early master photographer. I’m not sure the Portuguese parliament had funding this type of sojourn in mind while discussing Queen Maria Pia’s expenses in the 1870s, or that they had anticipated her response, “If you want a queen, you have to pay for her.” But perhaps presciently, she

had realized that strong, dignified portraiture in this increasingly popular medium could solidify the native Portuguese perception of the foreign-born queen as a branding and marketing tool, and that Relvas was just the man to produce this for her.

Carlos Augusto de Mascarenhas Relvas de Campos was born and grew up in the Outeiro Palace in this sleepy town in 1838, just in time to be alive when photography was invented several months later in England and France. He came from a family with vast land holdings in the area and was a renowned amateur bullfighter, both on horseback, as a cavaleiro, and off, as a bandarilheiro, the person who thrusts the banderillas, or darts into the bull’s neck and shoulders. He donated a bullring to Golegã, a town known since the eighteenth century as the “Capital do Cavalo,” or Horse Capital of Portugal. At fifteen, he married Margarita Amália Mendes de Azevedo e Vasconcelos, a Portuguese aristocrat from a neighboring town, and they quickly had four children.

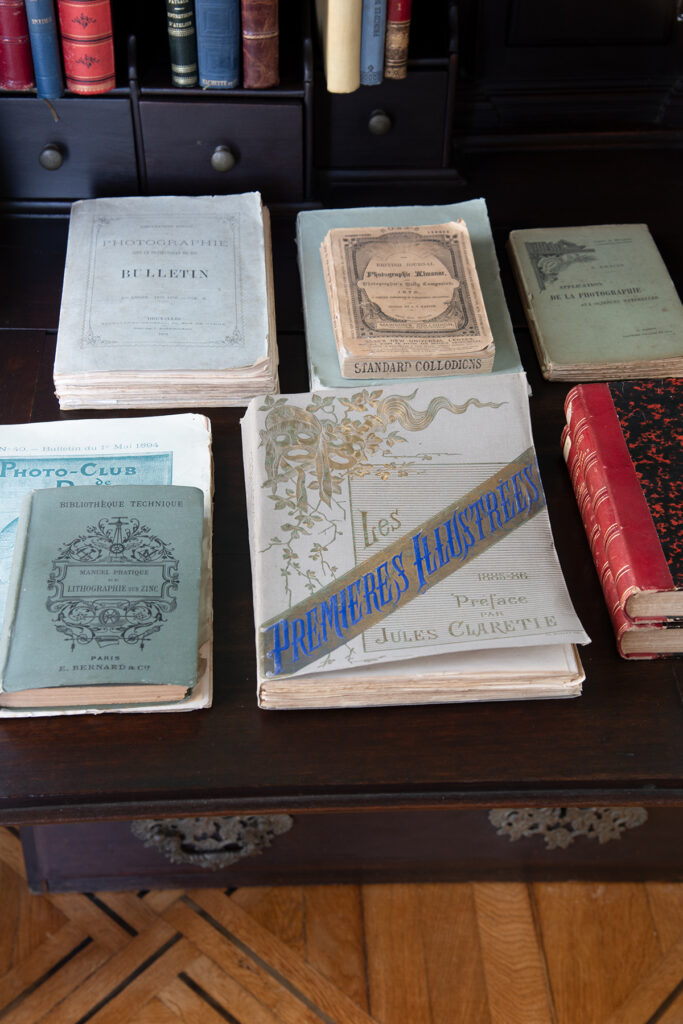

Relvas’s first exhibition was in 1868 at the Sociedede Promotora das Bellas Artes in Lisbon. As his interest in the medium developed in the 1860s, Relvas amassed a large collection of early photographic equipment while traveling throughout Europe, slowly satisfying his curiosity by experimenting with the different techniques developed by his predecessors, including both the wet-and dry-plate collodion processes, the collotype, and gum, carbon, and gelatin silver prints. He would continue to tinker and refine his photographic process throughout the 1870s and until his death in 1894 from sepsis following a horse-riding accident.

The Casa-Estúdio is an architectural anomaly. Except for Henry Fox Talbot, with his studio at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, England, and Irish aristocrat Lady Mary Rosse, whose digs were in Birr Castle, most early practitioners of photography worked in quite humble environments. When Relvas built his studio, the Gothic revival style was taking hold in Portugal, with many aristocratic houses in nearby Sintra designed in the style, which offered a counterpoint to the classicism that had preceded it there since the 1790s.

Expressing the esteem in which he held his space, Relvas photographed the entire construction of his atelier, documenting each stage as the Gothic traceries and iron rib vaults were crafted and installed. Inside, there is a room dedicated to the mixing of chemicals, a beautifully designed darkroom, multiple reception rooms for royal and noble clientele, and the studio itself, which, in its Gothic exuberance, directs the eye toward heaven, or, in this case the sun. Relvas developed a complex system of curtains that could be manipulated to address the lighting he thought would best serve each picture. Most daylight studios at the time, and for years to come, were lit solely by a northern skylight, which provided a soft, even light.

In his cleverly designed workspace, Relvas conceived of a multiplex studio, capable of housing several set-ups and unlimited lighting options. His sitters included sportsmen and commoners, as well as the queen and other aristocrats. In addition, he completed a comprehensive series of self-portraits (some displaying his wicked sense of humor) in an abundance rivalling those of Cindy Sherman. Like Sherman, Relvas dressed himself (or sometimes undressed himself completely) in costumes, appearing as a shepherd, a bullfighter, or on horseback in a jockey’s silks.

The obsessive focus that certain photographers have trained on themselves since the first selfie that Robert Cornelius captured in 1839 speaks to the relative ease and rapidity that the medium offered. It also speaks, perhaps, to the analytic nature of the medium and the immediacy of witnessing these self-examining results compared with painting. Henri Cartier-Bresson coined the phrase “The Decisive Moment” with the publication of his book of the same title, further explaining later that “Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera.” How better to train one’s eye, explore diverse personae, and achieve success in this arena than to use oneself as the model and photographer, providing immediate feedback?

Relvas also traveled extensively, photographing landscapes in Paris, Switzerland, and all over the Iberian Peninsula. But it was in this shrine to photography in which he preferred to work and where he eventually moved to spend the last years of his life.

In 2018–19 the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporanea do Chiado hosted an exhibition of his work. Despite a major exhibition, Carlos Relvas and the House of Photography, held in Lisbon at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in 2003 and showcasing around 350 works, as well as a 2018 exhibition at the Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea, Relvas’s spectacular photographic legacy has remained little known to the general public. Mark Haworth-Booth, then curator of photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London wrote for the catalogue that accompanied the exhibition, noting that “Relvas’s pictures were very good for his time . . . he created some of the most remarkable pictures of the nineteenth century. There is nothing similar in the world.”

Are we to assume that mock humility motivated him to inscribe all his images with “Carlos Relvas, Amateur Photographer, Golegã Portugal”? He knew his worth certainly, but perhaps he didn’t know that his place at the table would be resurrected in the twenty-first century. Happily, again, his eccentric grinning face is once more becoming a part of the history of the medium.

MARIO DE CASTRO is editor in chief of Soon magazine and has written several books including Seaside Style (Taschen).