In 1912, Walter Lippmann proclaimed: “Instead of a world once and for all fixed . . . we have a world bursting with new ideas, new plans, and new hope. The world was never so young as it is today, so impatient of old and crusty things.”1 Far from just the overenthusiastic ravings of a twenty-three-year-old aspiring journalist and critic, Lippmann’s optimism seemed to capture something essential about the spirit of the day. The revolutions that had propelled much of the world into the Industrial Age and altered every aspect of daily life—in communications, engineering, manufacturing, transportation—had in turn sparked concomitant revolutions in nearly every aspect of human endeavor. The era saw seismic developments that ranged from Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity to Sigmund Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, and in the United States as in Europe, the fever seized artists as well, who rejected academic realism in favor of styles that expressed their subjective responses to the dynamism of the modern age. As painter William Zorach recalled, “We entered a whole New World of form and color that opened up before us.”2

No country epitomized the modern era more than the United States, with its headlong embrace of everything new, from skyscrapers to subways. Yet as a relatively young nation, it was still something of a cultural backwater in the decade prior to World War I. To experience the latest avant-garde trends firsthand, American artists with progressive ambitions went to Paris.

But among the country’s emerging avant-garde who remained at home, many found inspiration in the ideas of the Massachusetts-born Arthur Wesley Dow, either by studying directly with him at the various institutions he taught at in New York from 1896 until 1922 or through his widely distributed book of art exercises Composition, first published in 1899.

Dow taught that art’s purpose was not to copy nature but to create harmonious designs that expressed the individual’s understanding of the world, and while he did not formally endorse abstraction, his focus on formal qualities over mimesis laid the groundwork for it. Artists already predisposed toward abstraction could see advanced American and European art at Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” gallery in New York. Stieglitz’s messianic insistence on the regenerative power of modern art and his impassioned support of vanguard artists in the face of public hostility made him the single most important force for modern art in America until 1913, when the International Exhibition of Modern Art opened in New York. Popularly known as the Armory Show for its hulking venue, the sprawling display organized by a collective of American artists scandalized scores of viewers with their first taste of the most advanced trends, from Henri Matisse’s fauvism to Marcel Duchamp’s cubist/futurist mélange. Yet for many American artists, the exhibition “blew everything wide open,” as artist Kenneth Hayes Miller observed.3 By expanding the definition of what was considered radical, the show offered artists an unlimited license to experiment: many who had previously been unaware of European vanguard styles suddenly embraced them; others who had already converted were empowered to become even more adventurous. No less significant to sustaining this fledgling avant-garde, new collectors emerged who supported modern art and new galleries opened to promote it.

The burgeoning of artistic talent that followed was far more diverse and exciting than often recounted by histories of this period, which have typically focused on the careers of a few individuals. A wider view of the work of America’s first wave of modernists provides a dazzling kaleidoscope that captures the delirious, combustible energy of a country possessed of youthful ebullience and an unshakeable belief in progress. The exhibition At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism examines this heady era. While the show brings together the work of celebrated artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, Oscar Bluemner, and Arthur Dove, the presentation devotes equal attention to their groundbreaking peers who are less well known today. Here are the stories of a few of them:

Albert Bloch

Albert Bloch began his career as an illustrator and caricaturist for the St. Louis satirical weekly The Mirror. In 1909 the journal’s editor financed his extended trip to Munich, home to the legendary illustrated magazines Simplicissimus and Jugend. A visit to Paris the following year whetted his enthusiasm for modern art; by 1911 he was painting circus scenes and performers with a van Gogh-inspired thick impasto. Seeing reproductions of Wassily Kandinsky’s work inspired him to adopt high-keyed, prismatic color for symbolic purposes. The work caught the attention of both Kandinsky and Franz Marc, who were organizing a group of German and Russian expressionist painters in Munich under the name Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Bloch’s work allied perfectly with the two artists’ dedication to making art that expressed spiritual values, and they invited him to exhibit six paintings in the group’s debut exhibition at Munich’s Galerie Thannhauser in December 1911. Bloch participated in subsequent major exhibitions of modern art in Germany until the onset of World War I. By then, his reputation as the only American member of Der Blaue Reiter had reached America. The Chicago-based collector and writer Arthur Jerome Eddy began buying Bloch works at the recommendation of Kandinsky, and he arranged to exhibit twenty-five of them in a solo-artist show at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1915. The fame proved fleeting. When Bloch finally returned to the United States in 1921 after more than a decade abroad, he found a country uninterested in his spiritually inclined art. To support his family, he took a job teaching at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, where he remained until his death in 1961.

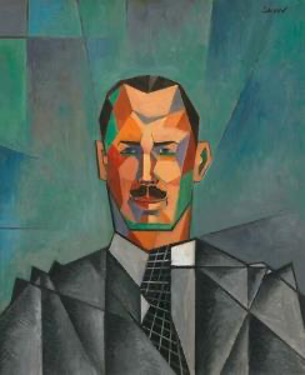

Yun Gee

At age fifteen, Yun Gee emigrated from China to San Francisco to join his Chinese merchant father, who had obtained US citizenship by convincing authorities that his birth records had been lost in the city’s massive 1906 earthquake and fire. Three years after arriving, Gee began studying at the California School of Fine Art under Otis Oldfield, who had just returned from a thirteen-year sojourn in Paris. From Oldfield, Gee learned to use quasi-geometric shapes of contrasting warm and cool colors to create three-dimensional rhythms across the surface of his compositions. Asked once why he did not paint using traditional Chinese techniques, he replied, “Because I am living in a modern industrial society.”4 He established a balance between his Chinese and American identities not only by painting images of San Francisco’s Chinatown in a Western style and by co-founding the cooperative Modern Gallery with Oldfield in 1926, but also as the founder of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists Club, where he taught classes in advanced painting techniques and color theory to young immigrants.

Gee left San Francisco in 1927 for Paris and found acclaim for his modernist depictions of Asian subjects. The onset of the Depression precipitated relocation to New York. There he exhibited in important venues, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, while also participating in demonstrations for victims of a horrific 1931 flood in China and making political cartoons for Chinese-language newspapers following Japan’s invasion of Manchuria that same year. Struggling financially despite critical success, he returned to Paris in 1936 only to retreat again to New York with the outbreak of World War II. After receiving modest recognition for the expressionist figurative style he adopted, his career began to fade, with only infrequent exhibitions of his art. Not until the 1980s would he be celebrated for his distinct contributions to American modernism as the leading Chinese American artist of the first half of the twentieth century.

Agnes Pelton

Agnes Pelton was born in Germany to American parents. A shy, emotionally fragile child, she studied as a teenager with Arthur Wesley Dow at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. Her artistic breakthrough came in the mid-1920s in a series of abstract paintings depicting intangible subject matter such as air, light, water, and sound. In the decades that followed, as she began to immerse herself in the study of esoteric religions and occult philosophy, her subjects and imagery evolved. She typically paired the emotive power of ethereal abstract forms with mystical symbols such as stars, mountains, and fire to portray her experience of attaining union with what she called “divine reality” through dreams and meditation.

As did a number of her artistic peers, Pelton believed color could speak directly to the soul. To further its emotional power, and suggest the relinquishing of ego that she felt was necessary for spiritual growth, she constructed her compositions out of multiple layers of smooth, thin glazes of paint that created delicate, shimmering veils of color. Living apart from the mainstream art world for most of her career, first in the relatively secluded East End of Long Island and later in the Southern California desert, Pelton received little encouragement. Her greatest support came between 1938 and 1942 from artists in the short-lived Transcendental Painting Group of New Mexico, who shared her belief that abstract art was a vehicle for enlightenment. Not until the 1980s did her efforts to depict “windows of illumination” onto the spiritual world receive the wider art world’s attention.

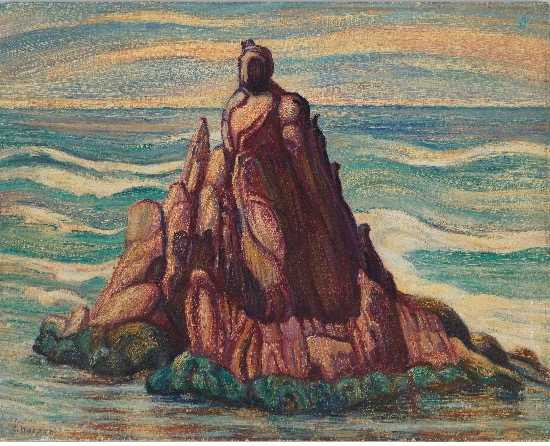

Henrietta Shore

Canadian-born Henrietta Shore moved to New York and in 1902 began to study with Robert Henri, the influential leader of the Ashcan movement in art, who called her one of his most important students. She moved to Los Angeles in 1913 but returned frequently to New York for extended periods. Her experience of East Coast avant-garde trends, combined with the modernity of her portraits and genre scenes, made her a key figure in the Los Angeles art world throughout the second decade of the twentieth century.

Back in New York in 1920, Shore radically shifted her style to boldly simplified distillations of organic forms infused with symbolic meaning. Layers of thin, transparent glazes of color endowed her abstractions with an extraordinary luminosity, as if light were emanating from within the canvas itself. The paintings debuted to great acclaim in 1923 in mid-career retrospectives at New York’s Ehrich Gallery and the Worcester Art Museum. Success followed upon success.

One of her greatest champions was modernist photographer Edward Weston, who credited a 1927 visit to her studio with influencing all of his subsequent work. After he moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, in 1929, Shore relocated there a year later. During the next few years, she transformed the craggy coastline of Point Lobos into anthropomorphic landscapes replete with metaphoric allusions. She remained in Carmel the rest of her life, but found herself increasingly isolated. Although her work was the subject of several retrospectives in the early 1930s, few sales resulted, and Shore’s primary income during the decade came from New Deal mural commissions. In 1937 she apparently stopped painting entirely. The last two decades of her life were spent in obscurity.

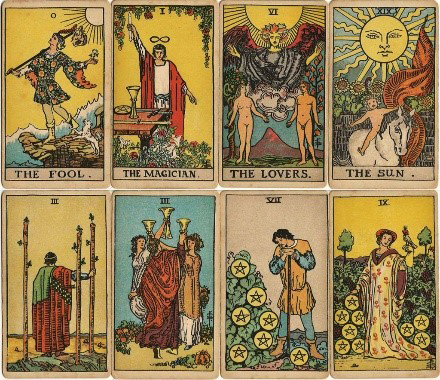

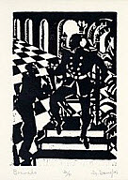

Pamela Colman Smith

Born in London to American parents, Pamela Colman Smith spent most of her early life moving between London, New York, and Jamaica. She began her art studies at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute with Arthur Wesley Dow, from whom she learned to work with flat chromatic shapes and decorative patterns of lights and darks. Merging Dow’s view that art was a form of personal expression with her own predilection for fantasy and magic, Smith became a successful book illustrator of folktales and children’s stories. She used these same narrative skills when designing costumes and sets for London’s Lyceum Theatre and performing Jamaican folktales for friends in the miniature wood-and-cardboard theater she constructed.

Through the Lyceum, she met Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who in 1901 introduced her to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society devoted to metaphysics and the occult. In 1909 fellow Golden Dawn member Arthur Edward Waite commissioned her to design a deck of tarot cards. Smith created fully illustrated, archetypal images for the entire deck, including minor arcana that previously had been decorated only with abstract symbols. Uniting the sinuous, flowing patterns of Japanese prints and art nouveau with the symbolic, lush imagery of English Pre-Raphaelite painting, Smith created a body of dreamlike images evocative of a spiritual realm.

In January 1907 she brought the work to Alfred Stieglitz at “291.” Up until then, he had only exhibited photographs, but Smith’s explanation that her images originated in her subconscious and had been liberated while listening to music aligned with Stieglitz’s interest in synesthesia and valorization of art as personal expression. He immediately hung her drawings in a one-person show, inaugurating a series of exhibitions at the gallery that would introduce US audiences to American and European vanguard fine art. Smith’s show was a critical and financial success, leading Stieglitz to exhibit her work twice more, in 1908 and 1909. By then, however, his attention had shifted to a new group of modernists, and she struggled to replicate the early success elsewhere. Discouraged, Smith abandoned art soon thereafter. She died in England in 1951, and though her tarot card designs have become iconic, her identity as their artist has often remained obscure.

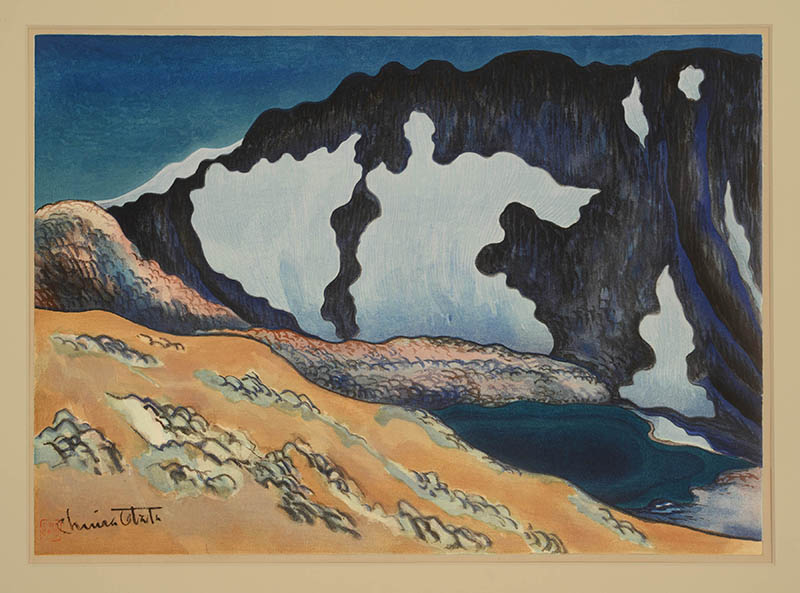

Chiura Obata

Eighteen-year-old Chiura Obata arrived in San Francisco from Japan in 1903, having studied sumi-e, the classical art of Japanese ink-and-bush painting, since the age of seven. Rather than abandon his heritage, he married the techniques and traditions of Asia and the West by fusing the fluid brushwork of sumi-e and the Zen-based principles of selflessness, calmness of mind, and reverence for nature with the naturalism of Western art.

Obata had been depicting the California landscape for over a decade when he took a six-week camping trip to Yosemite and the High Sierras in the summer of 1927. The trip yielded more than a hundred watercolors and drawings that were the basis of the portfolio of thirty-five color woodblock prints he made in Japan during an eighteen month visit there following his father’s death in 1928. Known as The World Landscape Series—“America,” they embodied Obata’s faith in the timeless, resilient forces of “great nature” as a source of spiritual sustenance.

Art, for Obata, was more than picture-making. His belief in its ability to transcend sociocultural differences and to give meaning to life led him to co-found the East West Art Society in San Francisco in 1921 and, in 1932, to begin teaching sumi-e painting and its underlying Buddhist philosophy to students at the University of California at Berkeley. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Obata became one of the thousands of Japanese Americans of the West Coast who were forced into internment camps. Obata responded by establishing art schools in the camps to help fellow inmates cope with displacement and loss. After the war, he resumed teaching sumi-e painting at the university and promoting Japanese art and culture in books, articles, and lectures.

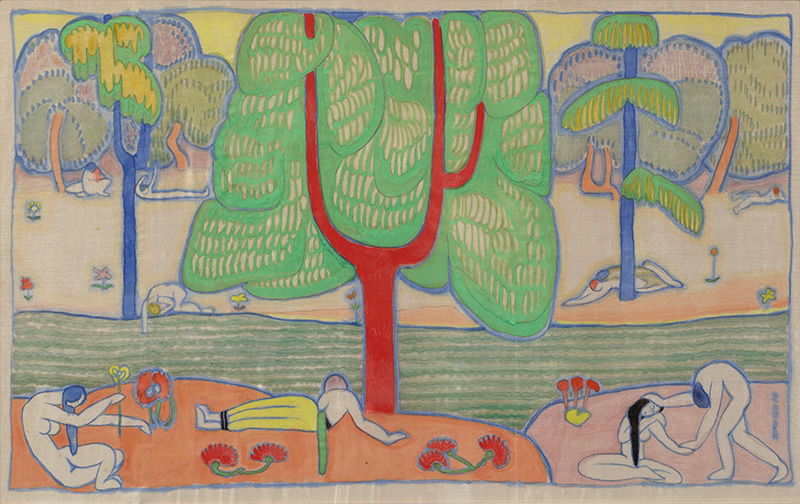

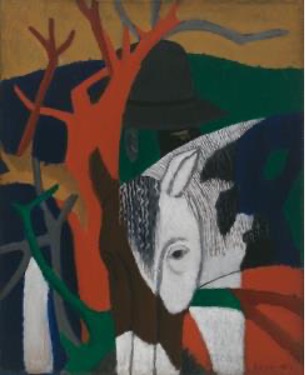

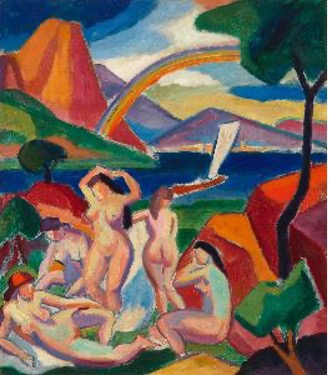

Marguerite Zorach

Marguerite Zorach (née Thompson) had just entered Stanford University in the fall of 1908 when she accepted her aunt’s invitation to join her in Paris. On her first day, she visited the Salon d’Automne, with its large display of fauvist paintings and soon thereafter met a childhood friend of her aunt: Gertrude Stein. Already by late 1908 Zorach was uniting fauvist color and compressed space with the cloisonnisme technique of delineating areas of color with dark outlines that Paul Gauguin had pioneered.

The boldness of her art caught the attention of American painter William Finkelstein in 1911 while the two were studying at the Académie de la Palette. The couple married in New York in December the following year, choosing the last name “Zorach,” which had been William’s given first name prior to his family’s emigration from Lithuania. The Armory Show opened a few months after their arrival in the city and included work by each of them. Marguerite, inspired in particular by the thirteen Matisse paintings on view, inaugurated a series of sinuous, brilliantly colored Arcadian landscapes that recalled the French artist’s nudes of 1906–07. She retained this style and subject matter through 1916, when the predominance of cubism in New York that followed the arrival of French cubists Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia led her to adopt a more somber palette, fractured vocabulary, and densely packed pictorial space.

By then, the mother of two young children increasingly devoted her energies to making what she called “tapestry paintings,” which she could work on sporadically. The dyed wool, she thought, yielded richer color than was possible with oil paint. These works, along with commissions for hooked rugs and embroidered bedspreads, generated crucial financial support for the family but clouded the art establishment’s view of her. When she actively resumed painting in the 1940s, it was in a figurative style associated with American scene painting.

Ben Benn

Born in Ukraine, Benjamin Rosenberg emigrated with his family to New York when he was fifteen and changed his name to Ben Benn. A chance visit to the Museum of National History in 1902 inspired him to become an artist. He trained for four years at the conservative National Academy of Design but quickly converted to modern art after seeing the Armory Show. His successful assimilation of Cubism and Fauvism was confirmed by his inclusion three years later in the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters, the ambitious survey at the Anderson Galleries in New York of the work of seventeen of America’s foremost modernists that was meant to refute the impression left by the Armory Show that American art was provincial and insular. In the 1920s, the shallow space and flattened geometric forms of Benn’s modernist work gave way to calligraphic, gestural flourishes and a sensuous application of paint that recalled the work of El Greco, whose 1915 exhibition at New York’s Knoedler Gallery had deeply impressed him. What remained constant during Benn’s sixty-year career was his commitment to painting the world around him, his work anchored in representational subject matter even as it enthused in elements of abstraction. “One must start with the facts,” he once said. The painterly joy and vigor with which he did so earned him a prominent place in the art world, with retrospective exhibitions at the Jewish Museum, Walker Art Center, and the Hirshhorn Museum.

Oscar Bluemner

German-born Oscar Bluemner arrived in the United States in 1892 at age twenty-five as an architect. By 1908, he had turned to fine art and become a member of the circle of modernist painters surrounding Alfred Stieglitz and his “291” gallery. Like others in the circle, Bluemner rejected pictorial realism in favor of art that communicated emotions. For him, color was key. His first group of modernist paintings employed flat, geometric planes of high-key color to depict the industrial landscape of New Jersey, yet when they were exhibited at “291” in November 1915, not even their bold, arresting aesthetic could withstand the rising tide of anti-German sentiment. Critics denounced Bluemner’s work as “alien” and “malevolent,” with the result that nothing sold. Undeterred, Bluemnerfocused on depicting what he called “the life movement of the spirit” by densely layering arabesques and rounded forms beneath glossy, jewellike surfaces that he created by adding banana varnish and formaldehyde to his oil point so the end result resembled lacquer. Bluemner had long linked individual colors with specific emotional qualities. In 1930, he began to associate shapes as well with psychological states in order to depict archetypal human dramas. A critically successful exhibition of these works in 1935 at New York’s Marie Harriman Gallery seemed to signal a change in Bluemner’s financial fortunes, which previously had teetered on the edge of poverty. Tragically, just after the show opened, he was hit by a car and soon suffered a cascade of health issues: stomach ulcers, liver damage, leg inflammation, and most debilitating, eye cancer, which left him unable to read or paint. Bluemner had never doubted his gifts as an artist, but unable to do anything other than lie in bed, he committed suicide in January 1938.

Patrick Henry Bruce

Patrick Henry Bruce was born into an old Virginia family that included among its forebears his namesake, American founding father Patrick Henry. Bruce studied in New York with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri before moving in 1904 to Paris, where he became friends with key members of the French capital’s avant-garde, in particular Henri Matisse, whose school he joined upon its founding in 1908, and the Orphist painters Sonia and Robert Delaunay. By 1912, he was joining the vivid colors in their work with the flat, geometric planes of Synthetic Cubism to create tabletop still lifes whose components he rendered as crisply delineated cylinders, cubes, and wedges seen from different perspectives. Bruce often included a vertical bar on the left side of his compositions to assert the flatness of the canvas surface while simultaneously creating the illusion that the depicted objects existed in deep space. The resulting pictorial tension evoked modernity’s pulsating energy. Despite positive response to his art from his French peers, Bruce became increasingly depressed and isolated. He destroyed most of his paintings, and in July 1936, after more than three decades abroad, he returned to New York to live with his sister, only to take his own life four month later.

E. E. Cummings

E. E. Cummings was committed throughout his career to what he called his “twin obsessions,” painting and poetry, though he undeniably became best known for his work in the latter. Yet when he arrived in New York in 1917 after graduating from Harvard, he set out to establish himself as a modernist in both fields. His Harvard connections gained him entrée at the influential literary magazine The Dial where he began publishing line drawing and caricatures as he absorbed the latest trends in painting at shows around the city. Inspired by the theories of Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, whose Synchromist style posited parallels between color and music, Cummings began using spiraling color planes to create visual equivalents of sound. Included in exhibitions at the Society of Independent Artists, his Sound and Noise paintings as he called them were favorably received. Nevertheless, shortly after returning to New York in December 1924 from a three-year sojourn in Paris and painting Noise Number 13, he adopted a more representational style. He continued to divide his time between painting and writing for the remainder of his life, but his paintings that followed were rarely exhibited and his renown as a poet came to overshadow recognition of his visual art, which was seen as merely a footnote to his writing career.

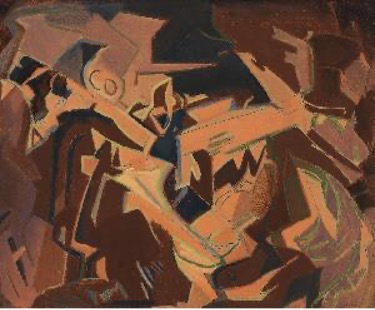

Manierre Dawson

As a high-school student in Chicago, Manierre Dawson was introduced to Arthur Wesley Dow’s influential instruction manual of 1899, Composition, which exhorted young artists not to imitate nature but to strive for harmonious arrangements of line, color, and mass. These lessons stayed with Dawson even after he began his studies in civil engineering at what is today the Illinois Institute of Technology and joined the Chicago architectural firm of Holabird and Roche. During his spare time, he painted a suite of completely nonrepresentational works composed of boldly colored lines, grids, and parabolas that many consider the first completely abstract paintings to have been made anywhere. In June 1910, after a year at the firm, Dawson left on a six-month sabbatical to Europe, whereupon returning to Chicago, he extended his painting experiments in a series of works that consist of angular, interlocking, brown-hued geometric shapes that create the sensation of movement across the two-dimensional plane of the canvas. The inclusion of one of these paintings in the Chicago presentation of the Armory Show inspired Dawson to quit his job at Holabird and Roche and devote himself entirely to his art. Convinced that he could best do that without the financial burdens of city life, he borrowed money from his family in 1914 and bought a fruit farm in Ludington, Michigan. At first, he successfully divided his time between art and farming, but eventually, the demands of farming prevailed. His last dated painting is 1920.

Aaron Douglas

A native Kansan and graduate of the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Aaron Douglas was a high-school art teacher in Kansas City, Missouri when he decided in 1925 to move to Harlem so he could “try to be what I believe I can be, where I can achieve free from the petty irritations of color restrictions,” as he put it. Douglas had been keeping abreast of the cultural renaissance happening in Harlem through the pages of The Crisis, published by the NAACP, and the National Urban League’s Opportunity, but it was the special 1925 issue of Survey Graphic entitled “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” which chronicled the mass migration to Harlem of African American intellectuals, writers, artists and musicians, that cemented decision to move there and become part of the movement of artists and writers who were giving powerful new expression to the experience of being Black in America. Upon arriving in Harlem, Douglas won a two-year scholarship to study with Winold Reiss, the German émigré artist who had illustrated Survey Graphic’s Harlem issue. Reiss introduced Douglas to European modernism while also encouraging him to draw on jazz and his African heritage. The distinct two-dimensional, angular silhouettes that Douglas created through a synthesis of German folk cutouts, Art Deco, Cubism, and Egyptian wall painting soon became a visual trademark of the Harlem Renaissance.

Douglas’s initial success was as an illustrator. Following the inclusion of his work in The New Negro: An Interpretation, the expanded edition of Survey Graphic’sHarlem issue, numerous commissions followed from the editors of The Crisis and Opportunity, as well as from writers of the Harlem Renaissance to illustrate publications of their work, including major commissions from Langston Hughes and James Weldon Johnson. In the 1930s, Douglas shifted his focus to easel paintings and to murals that monumentalized the Black experience in America, from its roots in Africa through enslavement, the struggle for emancipation to freedom. . Throughout these decades, Douglas actively supported the Harlem art community, cofounding the short-lived Fire!! A Quarterly Journal Devoted to the Young Negro Artists in 1926 and, in 1935, helping to form the Harlem Artists Guild. In 1939, Douglas joined the faculty of Nashville’s Fisk University, the historically Black university whose art department he led for nearly three decades.

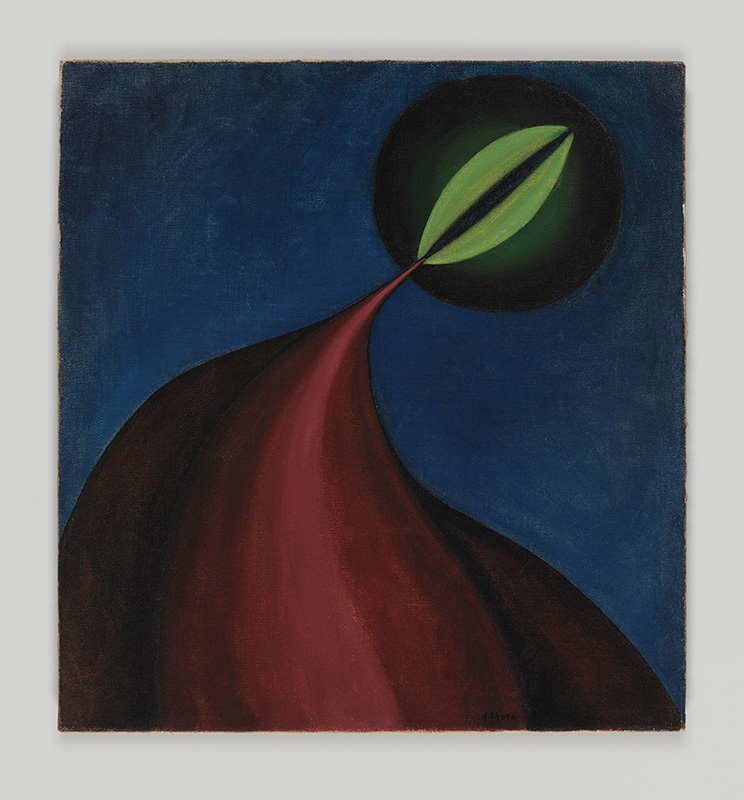

Arthur Dove

Arthur Dove began his career as an illustrator and urban realist but turned to nonrepresentational art during a two-year stay in Paris, where he exhibited in the Salon d’Automne. When he returned to New York in 1909, artist Alfred Maurer arranged an introduction with Alfred Stieglitz, who had recently decided to expand beyond photography to exhibit vanguard fine art at his “291” gallery. Stieglitz included Dove’s work in the gallery’s 1910 Younger American Painters exhibition, initiating a relationship that Dove would call central to his development as an artist. In 1911, Dove began a series of pastels that are among the first abstract paintings made in America. Using a vocabulary of swelling organic forms that radiate outward in pulsing halos of modulated color, he portrayed the universal rhythms and life force he believed animated all living things. For the rest of his career, whether he was on Long Island or back in his hometown of Geneva, New York, Dove deployed overlapping and interpenetrating circular shapes, graduated in concentric bands of color, to express his sense of oneness with nature. After a heart attack in 1939, he turned to flatter, more geometric planes of color to depict the underlying essences of reality.

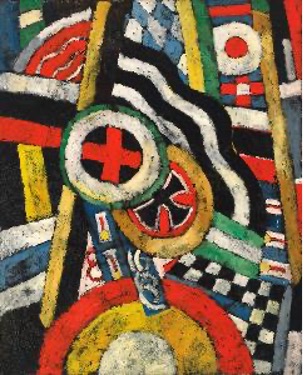

Marsden Hartley

Marsden Hartley traveled to Paris in 1912, where he quickly assimilated the fractured forms of Cubism, the vivid colors of Fauvism, and the spiritual content of German Expressionism. A year later, he relocated to Berlin, whose crowds, gay subculture, and military pageantry enthralled him. Shortly after World War I broke out, Karl von Freyburg, a German officer in the Royal Guards who Hartley loved, was killed. Devastated by his loss, Hartley juxtaposed images he associated with Freyburg, including German imperial flags, military emblems, fragments of the Royal Guards’ uniforms, and a chessboard, to create abstract portraits of him. Hartley returned to New York to find a country mobilizing to join the Allies. Forced to abandon his German military subject matter, he spent the next two decades moving from place to place in search of an equally compelling subject. Finally, in 1937, he returned to his home state of Maine, where he created a series of expressive landscapes and figure paintings imbued with a transcendent spirituality and haunting longing.

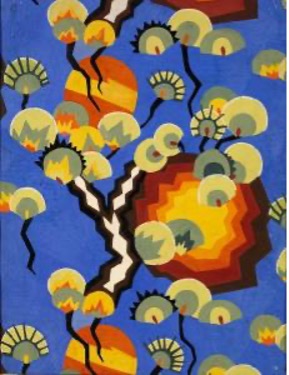

Loïs Mailou Jones

Born to middle-class Black parents in Boston, Loïs Mailou Jones attended the city’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, yet upon graduation opted to become a textile designer because she felt the anonymity of most designers would mitigate gender and racial discrimination. The commercial designs she created for the upholstery fabric cretonne beginning in 1926 were inspired by the art and aesthetics of a wide variety of non-Western cultures, including those of Asia, Africa, and Indigenous North America. Eventually, however, lack of recognition proved unsatisfactory. As Jones recalled, “I realized I would have to think seriously about changing my profession if I were to be known by name.” In 1930, Alain Locke, the Black theorist and intellectual godfather of the Harlem Renaissance, hired her to teach at Howard University. Encouraged by Locke to look to Africa for aesthetic inspiration, Jones incorporated African motifs and subjects into her art while retaining the dramatic, decorative patterning and high-keyed color she had used in her textile designs. Following her marriage in 1953 to Haitian artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel and her subsequent trips to Haiti and Africa, her paintings became more geometric and even more colorful.

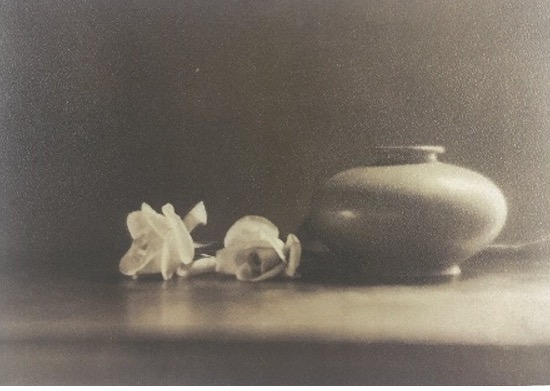

Taizo Kato

Taizo Kato immigrated to the United States from Japan in 1906 at the age of nineteen, eventually settling in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo with his domestic partner, Kamejiro Sawa. There, the men opened a series of shops, each called The Korin, where they processed and printed photographs and sold cameras, photographs, ceramics, stationery, frames, and paintings. As one of the area’s early Japanese art photographers, Kato joined the soft-focus, atmospheric qualities of pictorial photography with an appreciation for the transitory nature of life. Whether the subjects of his photographs were landscapes, still lifes, or people, his suppression of detail and emphasis on voids engendered a mood of reverie and mystery that accorded with the absolute stillness and “emptiness of mind” he associated with Zen Buddhism. He was not alone in his ambition to marry aspects of Western modern art with Japanese traditions and sensibility. The goal was shared by members of Shaku-do-sha, a club founded by Japanese painters, poets, and photographers in Little Tokyo who regularly met to exchange ideas and exhibit their art. Kato was an active member, participating in programs and writing reviews for the club’s shows. One of his last reviews was for a 1923 exhibition of paintings by seven of the club’s members. Kato died suddenly in January 1924 of unknown causes, at the age of thirty-six.

Blanche Lazzell

Born in a small farming community in West Virginia, Blanche Lazzell studied in New York and Paris, then spent the summer of 1915 in Provincetown, Massachusetts, along with other American artists who were unable to go to Europe because of World War I. Among them was a group of women printmakers who were experimenting with the white-line woodcut. Lazzell quickly became a leading exponent of the process, which involved cutting a design into a single block of wood, then applying a water-based paint to one of the raised areas and pressing paper onto that area with the hand or a spoon. Repeating the process for each raised area resulted in white embossed lines between forms in the finished print. Each block could yield multiple prints, each having the same design but different colors. Between 1923 and 1925, Lazzell returned to Paris and studied with Cubist painters Albert Gleizes, André Lhote, and Fernand Léger. The group of abstract woodblock prints she made in response are among the earliest examples of nonrepresentational prints in the United States. Mostly, however, she employed Cubism’s flat, geometric planes of color to depict Provincetown’s houses, rooftops, wharves, and gardens. Using French watercolor pigments and exploiting the grain of the woodblock to create striated patterns, she transformed her landscape and still-life subjects into rhythmic interplays of flat, softly hued shapes whose overall impact was that of a watercolor.

Stanton Macdonald-Wright

Stanton Macdonald-Wright grew up in Los Angeles and, at seventeen, set off for Paris to encounter modern art firsthand, arriving in late summer 1907. Four year later, in a painting class taught by color theorist Percyval Tudor-Hart, he met Morgan Russell, a fellow American, and the two set out to formulate a new art movement predicated on the properties of color to visually advance or recede and thus create the impression of sculptural volumes on the two-dimensional canvas surface. Calling themselves Synchromists, they proposed that color was analogous to music and could similarly induce psychological and emotional responses without the need for narrative or literal representation. They debuted their movement in an exhibition at Munich’s Der Neue Kunstsalon in June 1913 and at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in Paris several months later. Not surprisingly given Synchromism’s desire to emulate sculpture, Macdonald-Wright produced very few pure abstractions, preferring instead to embed figurative elements into his compositions, overlapping transparent planes of luminous color to create the illusion of twisting, spiraling sculptural forms. In 1916, he moved to New York to participate in the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters and, a year later, had a one-person exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” gallery. Struggling financially, he returned to his hometown of Los Angeles in 1918, where for decades he was the leading force for modernism in the city, teaching, writing, organizing exhibitions, and serving as director of the Los Angeles Art Students League and director of the New Deal–era Federal Arts Project for Southern California.

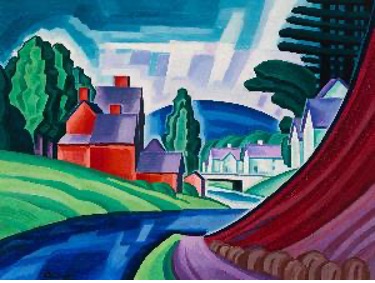

Carl Newman

Carl Newman was a fifty-two-year-old Pennsylvania Academy–trained figure painter when he spent the summer of 1910 in Paris with Henry Lyman Saÿen, his close friend and fellow Philadelphia artist who had been living in Paris for seven years and had converted to Fauvism. Working alongside Saÿen that summer, Newman loosened his brushwork and brightened his palette. After Saÿen returned to Philadelphia in 1914, the two artists began spending almost every weekend together north of the city in Bethayres, where Newman had built a large house and studio. In 1915, Newman commissioned Saÿen to decorate the studio’s eighteen-foot-high ceiling. Working with Saÿen’s Fauvist kaleidoscope of color overhead, Newman inaugurated a series of brightly colored landscapes that recall Matisse’s 1905 Joy of Life, which he would have seen in Paris while attending Gertrude Stein’s salon in 1910 with Saÿen. As his work evolved during the next decade, it came to be dominated by large-scale nude female figures. Unabashed in their voluptuousness, they shocked American audiences to such an extent that one of the paintings was removed once from an exhibition because of viewer complaints. In a misguided effort to salvage her husband’s reputation, Newman’s wife destroyed many of these later figure paintings after the artist’s death.

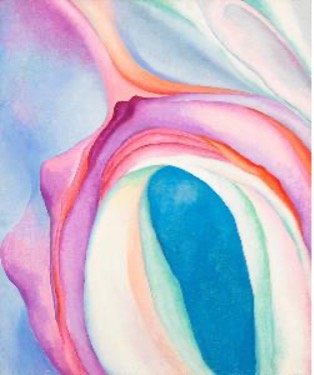

Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe attended the school of the Art Institute of Chicago and New York’s Art Students League, but it was the ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow that she encountered at the University of Virginia during the summers of 1912 through 1914 that were pivotal to her development as an artist. Inspired by Dow’s belief that an artist’s purpose was not to copy nature but to create harmonious designs that expressed her subjective experience of the world, O’Keeffe enrolled in Dow’s class at Columbia University for the 1914–15 term and began to visit Alfred Stieglitz’s “291” gallery to absorb contemporaneous currents in modern art. That fall, while teaching at Columbia College in South Carolina, she produced a group of charcoal abstractions that a friend showed to Stieglitz. His exhibition of them in a three-person show in 1916 initiated a professional and romantic relationship between the two that lasted until Stieglitz’s death in 1946. Between 1916 and 1918, while teaching art in Canyon, Texas, O’Keeffe created boldly colored, abstract watercolors inspired by the West Texas landscape. Even after she moved to New York in 1918 and adopted oil as her primary medium, she continued to work abstractly, using a vocabulary of undulating, biomorphic forms to suggest the flowing rhythms of the natural world. In the early 1920s, distraught that her abstractions were being interpreted as sexual, O’Keeffe adopted a more representational vocabulary to depict subjects ranging from New York skyscrapers and flowers, to the natural environs of the Stieglitz summer house in Lake George. In 1929, O’Keeffe visited New Mexico for the first time, and settled permanently there in 1949. For the next twenty years, she continued to synthesize abstraction and representation to produce work that made visible her ineffable emotions.

Nancy Prophet

Nancy Prophet (née Proffitt) graduated in 1918 as a portrait painter from the Rhode Island School of Design, the sole African American among the predominantly white student population. Unable to obtain gallery representation and facing racial discrimination, she left for Paris in 1922 to study sculpture. She stayed for twelve years, sculpting busts and standing figures primarily in wood or plaster that conveyed a mixture of melancholy and stoicism. Although er work was included in the Salon d’Automne and exhibited at the Société des Artistes Français, few works ever sold, and Prophet’s frequent lack of food and proper lodging led to an extremely small output. She existed with the support of a few patrons, including American expatriate painter Henry Ossawa Tanner and writer and civil rights activist W. E. B. DuBois, both of whom encouraged her to return to the United States to promote her art. Her visit in 1932 led to multiple exhibitions of her work, her receipt of the Otto Kahn sculpture prize from the Harmon Foundation, and laudatory articles in The Crisis and Opportunity. For the next four years, Prophet moved between New York and Paris, returning permanently to the United States in 1934. Still unable to support herself from her sculpture, she took a job teaching art at Spelman College, the historically Black college for women in Atlanta. She remained there for ten years before retiring in 1944 to her hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, where she spent her final years in poverty and obscurity.

Charles G. Shaw

Born into a wealthy New York family linked to the Woolworth fortune, Charles Shaw spent the Roaring Twenties using his entrée into elite social circles to interview literary and show-business celebrities and to chronicle the nightlife of the well-to-do for The New Yorker, Smart Set, and Vanity Fair. Not until he was almost forty did he become serious about visual art. He studied for two years with Thomas Hart Benton as well as George Luks before leaving in September 1929 for Paris and London. By the time he returned to America in 1932, he was fluent in both geometric and biomorphic abstraction. Shaw was uncommonly gifted in a variety of aesthetic styles and media, including photography and collage, but his most original contribution was his series of Plastic Polygons whose rectangular motifs derived from Manhattan’s skyline. Often painted on shaped canvases with overlapping three-dimensional forms that evoke the heterogeneous massing of the city’s skyscrapers, the works are “solely of America,” as Shaw put it. Along with Suzy Frelinghuysen, Albert Gallatin, and George L. K. Morris, Shaw was one of the wealthy abstract artists known as the “Park Avenue Cubists.” In 1936, he became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group, the first association of its kind in the country. While primarily focused on visual art, Shaw continued to employ his literary talents to write novels, articles, poems, and children’s books and to advocate for abstract art, which he argued could “express life without using life’s images” and thereby deliver “the individual accent of our time.”

Adele Watson

Adele Watson was born into a prominent Toledo, Ohio family, yet as did any number of others during the late nineteenth century, she responded to the secular materialism of the Industrial Age by embracing spirituality. The paintings of Arthur B. Davies, which she saw in New York while studying at the Art Students League, provided the springboard for her early work. The introspective mystery and mythological allusions evoked by his dreamlike female nudes dancing in pastoral landscapes became central to her art after she relocated to Pasadena, California in 1917. She had known the city ever since the early 1890s when her family began wintering there for the health of her brother. The area was home to countless cults and exotic religions. Although she did not join any of them, their ubiquity liberated her to imbue her paintings of nymph-like female figures floating over Arcadian landscapes with an aura of otherworldly spirituality. Trips to Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks beginning in 1930 reoriented her sense of the spiritual structure of the universe. Rather than depicting woman and nature as distinct, as she had done previously, she pictured them as mystically united. Using expressive brushstrokes and a palette of earth tones, she created primeval anthropomorphic landscapes steeped with spiritual and mythological symbolism.

1 Walter Lippmann, quoted in Arthur Frank Wertheim, The New York Little Renaissance (New York: New York University Press, 1976), p. 6.

2 William Zorach, “Where is Sculpture Today?” typed lecture notes, 1931, p. 48, Zorach Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, microfilm, NY59-3.

3 Kenneth Hayes Miller to Rockwell Kent, March 23, 1913, reproduced in “The Armory Show: A Selection of Primary Documents,” Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 27, no. 2 (1987), p 31.

4 Yun Gee, quoted in Jane C. Ju, “In Search of Yun Gee, the Chinese American, and Modernist Painter,” in The Art of Yun Gee (Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 1992), p. 55.

At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through February 26, 2023.

Barbara Haskell has been a curator at the Whitney Museum since 1975 and is the curator of At the Dawn of a New Age.