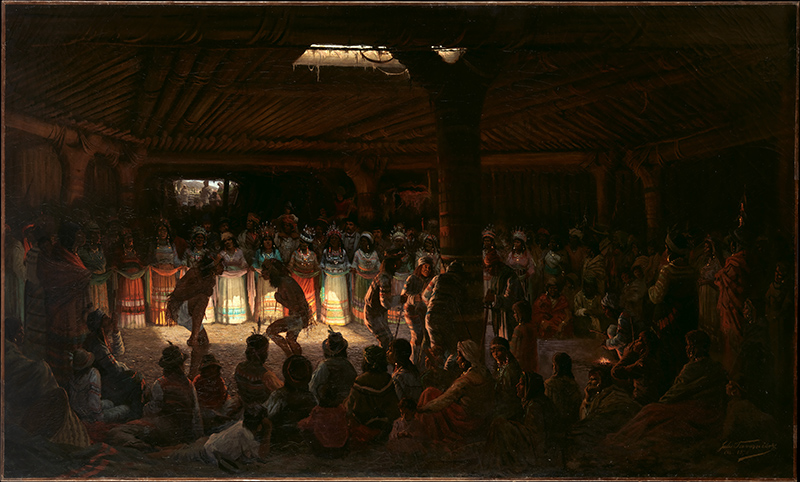

In 1876 San Francisco’s leading banker, Tiburcio Parrott, gave the French-born and -trained American artist Jules Tavernier the most important commission of his career. The resulting painting— Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California— commemorates an extraordinary experience Parrott shared with Parisian business associate Baron Edmond de Rothschild (Fig. 1). Earlier that year, both men were privileged to witness a ceremonial mfom Xe, or “people dance,” of the Elem Pomo, an Indigenous community on the southeastern shore of Clear Lake in northern California. While Tavernier’s work celebrates the rich vitality of Elem Pomo culture, it also exposes the threat posed by white settlers such as Parrott, who was then operating a toxic mercury mine on the community’s homelands. Designated a superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1990, the mine continues to have a negative impact on the lives of the sovereign people of the present-day Elem Indian Colony.

Presented in collaboration with Elem Pomo cultural leader and regalia maker Robert Joseph Geary and Dry Creek Pomo/Bodega Miwok scholar Sherrie Smith-Ferri, the new traveling exhibition Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo is anchored by Tavernier’s Roundhouse painting, which upon its completion was hailed in a San Francisco newspaper as “by far the most remarkable picture ever painted on the Pacific Coast.”1 Despite the public’s strong desire to see it, the work was never publicly exhibited in the United States. Instead, Parrott had it immediately shipped to Paris and presented as a gift to de Rothschild. For more than a century, it remained in private hands and was presumed lost until it was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2016. The following year, the Met received a landmark gift from collectors Charles and Valerie Diker of works of Native American art, including significant holdings of historic California basketry. These two momentous acquisitions inspired this exhibition, which features major works by Tavernier shown alongside historical and contemporary Pomo basketry and regalia to celebrate the resiliency of Indigenous Pomo peoples and highlight their continued cultural presence.

The rediscovery of Tavernier’s Roundhouse in recent times has inspired this new analysis of the artist’s career. As an aspiring painter, he spent four years (1861–1864) in the Paris studio of Félix-Joseph Barrias, a French academic artist known for his neoclassical history paintings.2 Tavernier took life drawing classes and exhibited his paintings at the Paris Salon in the later 1860s, where he was introduced to paintings of the American West and Indigenous peoples by European and American artists. He arrived in New York in 1871, initially showcasing his skills as an illustrator with scenes of daily life and the American wilderness. Following the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the American public clamored for images of the West. Tavernier’s talent was recognized by Harper’s Weekly, which hired him, along with fellow French artist Paul Frenzeny, to travel across the country, providing the magazine’s readers with tantalizing pictures. The men filled their sketchbooks with field studies of the conflicts they witnessed—a result of the rapid expansion of white settlement and the US government’s forced relocation of Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands (Fig. 3).

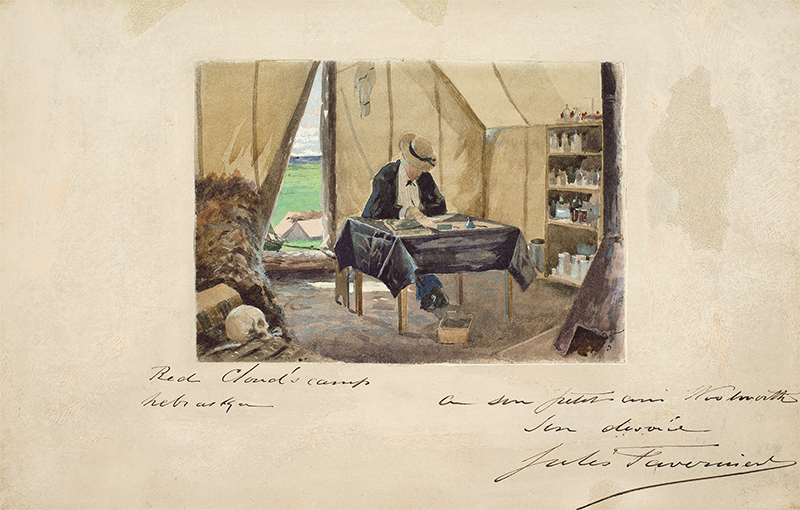

In May 1874, under the escort of an armed US cavalry unit, Tavernier began a month-long journey to the government-run Red Cloud Agency on the Platte River, downstream from Fort Laramie, Wyoming. The artist wrote to his mother, “I will be crossing one of the wildest areas around here, no artist has ever been. . . . I will meet [Red Cloud], one of the most important Indian Chiefs . . . I will see the real wild life.”3 He would capture the provisional nature of the camp in a series of field sketches (Fig. 2). Tavernier sought out direct interactions with Native Americans, taking portraits of Plains Indians and witnessing the Sun Dance ceremony, a weeklong gathering of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, where he met Red Cloud (Fig. 4). Our understanding of Tavernier’s work has been greatly enhanced by contemporary Indigenous voices and perspectives, and the exhibition features interpretations of his ceremonial Sun Dance pictures by Oglala Lakota artist, historian, and educator Arthur Amiotte.

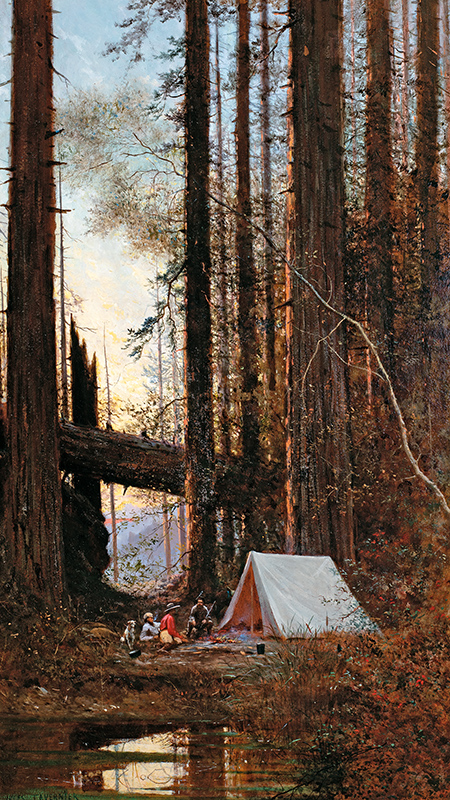

Tavernier eventually arrived by train in San Francisco by July 1874, and would become the region’s leading artist for the next decade. He served as a prominent member of the Bohemian Club and was a founder of the Monterey Peninsula Art Colony. He maintained a free-spirited lifestyle even as he explored the unique landscape of northern California, adapting a distinctive vertical format to capture the grandeur of the redwood forests in his landscapes (Fig. 5). Tavernier, who had painted in the famed artist colonies near the French village of Barbizon, was drawn to the Monterey Peninsula on the Pacific coast—an area that came to be known as a veritable Fontainebleau after the forest near Barbizon. In an enigmatic self-portrait, filled with anthropomorphic forms, including a female muse and Native American figures, he captured the eerie quality of the Monterey landscape (Fig. 6).

Many of his paintings directly address intercultural encounters, often violent, between Indigenous peoples and white settlers. In A Disputed Passage (In the Days of ’46) (Fig. 7), the artist chose to celebrate the US centennial of 1876 with a scene from the earlier Gold Rush era, which had disrupted, in devastating ways, the lives of Native Californians. The artist would complete at least thirty paintings of Indigenous people over the course of his brief career, culminating with his commission from Tiburcio Parrott. Tavernier spent two years working on this tour de force with nearly one hundred figures, including Elem Pomo dancers and musicians as well as non-Native onlookers, notably Parrott, de Rothschild, and their traveling companion Comte Gabriel Louis de Turenne d’Aynac, who wrote an extensive description of the experience in his journal. The artist rendered the dimly lit interior with brilliant technical finesse, meticulously depicting the architectural framework of the circular underground roundhouse, its shape symbolic of the life-sustaining form of a basket.

In his essay in the exhibition’s accompanying publication, Geary explains that the mfom Xe is “a newer ceremony that was introduced to our community in the post-contact period by a prophet from a neighboring village northeast of Elem. It was decided that the world-renewal process that had been prophesied, and which is the subject of the dance, needed to be practiced immediately because at the time the oomthimfo, or ‘native people,’ were dying in record numbers from destruction and diseases brought by new settlers.”4 In fact, by the time Tavernier arrived in California in 1874, Pomo peoples had already suffered for decades from the catastrophic consequences of white settlement, including genocidal violence, disease, land theft, forced relocation, environmental degradation, and cultural transformation. Yet, in the face of this devastation, Pomo communities developed strategies of resistance and survival that persist today. This includes both the roundhouse and the mfom Xe dance, which, Geary writes, “serve to protect both the people and the land.”5 Geary continues to lead ceremonies at Elem, and the exhibition features examples of regalia he created, including two ceremonial headpieces that demonstrate the continuum of Elem Pomo culture and the ongoing importance of the mfom Xe within the community today.

Fig. 8. Diagonally twined carrying basket by a Pomo artist, northern California, c. 1900. Willow shoot foundation, sedge root warp, redbud shoot weft, coiled-on oak rim rod, and split grapevine rim wrap; length 20, diameter 18 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Charles and Valerie Diker; photograph by Bruce Schwarz, © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 9. Twined basket and clay balls by Susana Bucknell Graves (c. 1866–1929) and Penn Graves (c. 1860– 1919), Habematolel Pomo of Upper Lake, California, 1908. Basket: tule foundation and weft; height 5, diameter 8 ½ inches. Balls: baked clay mixed with plant fiber; diameter of each 1 ½ inches. Brooklyn Museum.

In addition to examples of both historical and contemporary regalia, the exhibition features a selection of nineteenth- to twenty-first-century baskets— the art form for which the Pomo peoples are best known. Although baskets would not have been present inside the roundhouse during the mfom Xe ceremony, they were used above ground in the presentation of food. Nevertheless, Tavernier included two baskets in the roundhouse—at left, a large bell-shaped carrying basket, and, at right, a basket tray, similar in style to those in Figures 8 and 11, respectively. This artistic liberty speaks to Tavernier’s awareness of the significance of basketry in Elem Pomo life, as well as to the growing non-Native craze for collecting Pomo baskets at the end of the nineteenth century.

The baskets featured in the show were selected in close consultation with Smith-Ferri, who also wrote all the texts on basketry in the exhibition. As Smith- Ferri explains, “Baskets were the main tools of life: they were used to catch, gather, store, winnow, sift, cook, and serve these foodstuffs. In addition, baskets were central to individual and community events, serving as everything from a baby’s cradle to a part of ritualized marriage exchanges or celebrations of seasonal abundance.”6 Highlighting the diversity of weaving techniques employed by Pomo makers, the show includes twined and coiled pieces, such as those used for hunting (Fig. 9) and feasting (Fig. 10), as well as for storage (Fig. 14). Woven about 1900 by master Yokayo Pomo weaver Mary Knight Benson, the latter basket—known as a “boat” or “canoe” basket because of its elongated oval shape—was a type used by Indigenous healers to store items of power, and by others to keep items of value, such as strings of clamshell disc beads. Although the shape predates the art market, the basket’s size indicates that it was likely an aestheticized version made for sale to a white collector—an important means by which many weavers supported themselves and kept basketmaking practices alive within their communities.

Following sustained contact with white settler culture, Pomo peoples replaced many functional baskets with readily available manufactured products. The introduction of new, commercially made household goods had a profound impact on Pomo basketry over the next several decades, as makers began to produce fewer utilitarian works, focusing instead on pieces made for sale to non-Native collectors. For instance, when creating a feathered, coiled basket around 1900 (Fig. 12), Elem Pomo weaver Ethel Jamison Bogus incorporated multicolored mallard, woodpecker, and western meadowlark feathers as well as decorative clamshell disc beads and abalone pendants to enhance the value and collectability of the work. The finished basket reveals both her intimate knowledge of plant and animal species and her keen awareness of the art market, where small, colorful, and elaborately decorated baskets proved most popular. Emblematic of a long and enduring history of Indigenous innovation and adaptation, baskets such as these reveal the resiliency of Pomo weavers, who adapted long-held forms and techniques to meet the growing demands of the art market.

Basketmaking continues to be an important part of contemporary Pomo life and the exhibition also features a selection of recently made baskets by Dry Creek Pomo/Wappo/Wintun weaver Clint McKay. McKay learned basketmaking from his aunts, master weavers Laura Somersal and Mabel McKay. Both excelled at weaving miniatures—a practice with its origins in the Pomo tradition of making tiny baskets to hang from the rim of a baby’s cradle. McKay carries forth these practices today, creating exquisite pieces such as a miniature coiled basket (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Miniature three-rod coiled basket by Clint McKay (Dry Creek Pomo/ Wappo/Wintun, 1965–), c. 2010. Willow shoot foundation, sedge root weft, dyed bulrush root weft, California valley quail topknot feathers; height 2 ¼ inches. Collection of the artist.

Fig. 14. One-rod coiled boat basket by Mary Knight Benson (Yokayo Pomo, 1878–1930), c. 1905. Willow shoot foundation, sedge root weft, and dyed bulrush root weft; height 4 ½, width 22 ½, depth 10 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller; photograph by Peter Zeray, © Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition includes a small section dedicated to the end of Tavernier’s life in Hawai’i. Following the success of his masterful work, the artist’s bohemian ways—notably, many unpaid bills—prompted him to seek fresh horizons and new subjects for his art. He arrived in Hawai’i in 1884, where he painted a series of landscapes of the islands’ active volcanoes (Fig. 15). Healoha Johnston, curator of Asian Pacific American Women’s Cultural History at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, provided new interpretations of these late Hawaiian landscapes in gallery labels on the importance of Pele, the powerful female deity who embodies the many manifestations of volcanism, and who is revered by the islands’ Indigenous communities. Enriched by the art and stories of contemporary Native communities, the exhibition aims to amplify Indigenous voices and histories, drawing connections between settler and Indigenous artists, past and present, in order to develop a more inclusive history of American art.

Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to November 28, 2021, and at the de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco from December 18 to April 17, 2022. It is the subject of the current issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin.

1 “An Indian Sweat House,” San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser, June 8, 1878. 2 The exhibition benefitted greatly from previous scholars’ work on Tavernier, in particular, Joseph Baillio, Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake: The Masterpiece of the Franco-American Painter Jules Tavernier (1844–1889) (New York: Wildenstein, 2014); Claudine Chalmers, et al., Jules Tavernier: Artist and Adventurer (Portland, OR: Pomegrante/Sacramento, CA: Crocker Art Museum, 2014); and Claudine Chalmers, Chronicling the West for Harper’s: Coast to Coast with Frenzeny and Tavernier in 1873–1874 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013). 3 Jules Tavernier to Marie-Louise Rosalie Wolillome, May 7, 1874, collection of the artist’s grandniece Elaine Dumay. 4 Robert Joseph Geary, “Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 79, no. 1 (2021), p. 4. 5 Ibid. 6 Sherrie Smith-Ferri, “Pomo Basketmaking,” gallery text panel in Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo.

ELIZABETH KORNHAUSER, Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Painting and Sculpture at the Met and SHANNON VITTORIA, senior research associate, co-curated the exhibition in partnership with Christina Hellmich, Curator in Charge, Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the de Young Museum.