When the two chairs are seen side by side, they appear to be speaking different languages. Metal tubing clashes with delicate silver-gray birch; green upholstery and coral-pink paint face-off from opposing sides of the color wheel. Yet Eero Saarinen designed them both, at the same time, for adjacent spaces in the same building—the Kingswood School for Girls, part of the Cranbrook Educational Community in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Between 1929 and 1931, starting when he was just nineteen, Saarinen designed some thirty-five pieces of furniture for Kingswood. He was the son of architect Eliel Saarinen, who designed the Cranbrook campus. His mother, Loja Saarinen designed textiles, and his sister Pipsan was a colorist and interior designer. The family was an all-in-one design machine. From the silverware on the tables to the tables themselves, to the rugs on the floor to the ceilings and walls, the Saarinens created an aesthetic that was uniquely their own. For three years, Kingswood was their shared canvas.

Eliel and Loja were well-respected leaders of the Finnish arts and crafts movement when they moved to the American Midwest between the World Wars. There they built a relationship with George Gough Booth, a newspaper magnate and the founder of Cranbrook, who envisioned the place as a transformative cultural institution. In 1925, the year Eero turned fifteen, the family settled in Bloomfield Hills and began turning Booth’s project into a hub of arts and architectural achievement—designing, in addition to Kingswood, a boys’ school called simply Cranbrook School, the Cranbrook Academy of Art, and museums of science and art.

For the Saarinen family, life, work, and art were seamlessly intertwined—a “holy trinity” in the words of Kevin Adkisson, curatorial associate at the Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research. Working together, the family wrought an entire world at Cranbrook. The work was herculean in scale and monumental in cost. In the end, Booth gave Eero an unexpected bonus — the rights to his creations. Eero’s father would never be able to reproduce his own designs for Cranbrook, but Booth wanted Eero to use the Kingswood project as a launching pad. “It’s very telling,” Adkisson says, “that George Booth would share that with this young man.”

Those who see in black and white would likely emphasize one of Eero Saarinen’s chairs for Kingswood and disregard the other as a misstep. And yet, to hold both chairs in mind at the same time, and to see them as part of a unified whole, is to look beyond the singular. Perhaps that is what is so unique about the Saarinen family: this vision. They could see a past, imagine a future, and then bring the two together in a fully realized present. For Adkisson, the Kingswood chairs illustrate a notion of architect Robert A. M. Stern’s: the concept of parallel modernisms. Eero absorbed a range of developments in design—the lushness of the art deco style and Bauhaus functionalism—and created pieces that responded to and built upon both.

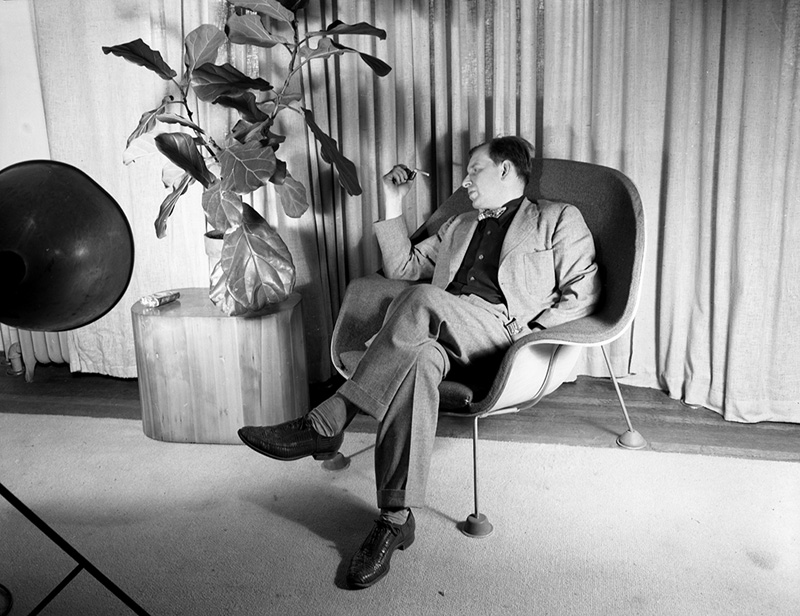

Eero worked under his father in the decades to come, but Eliel’s slowing pace in the 1940s gave his son greater opportunity to explore, incorporating new materials and manufacturing styles into his work. In 1948 Eero joined forces with Florence Knoll—a former Kingswood and Cranbrook Academy student and an unofficial member of the Saarinen family—and her husband, Hans, to design for their eponymous furniture company. One goal was to devise a chair that would be comfortable for all body types. The result was Saarinen’s Womb chair (1948)—to Adkisson’s mind, the high point in Eero’s furniture design career. One of the first plastic chairs to be mass-produced, it is still manufactured today—a remarkable feat for any design.

Yet for Saarinen the Womb chair had a problem, four of them: legs—the chief culprits of what he called the “ugly, confusing, unrestful world” below seats and tabletops. “We have chairs with four legs, with three and even with two, but no one has made one with just one leg, so that’s what we’ll do.” His solution emerged in 1957 when his Pedestal group—also known as the Tulip series—of chairs and tables that rise from “a single stem” debuted. They, too, are still in production.

Just four years later, Saarinen died at the age of fifty-one, having spent only eleven years outside his father’s shadow. His technical curiosity and adventurousness in materials may have only just begun to reveal itself. Today, his Kingswood designs remain cherished pieces of the Cranbrook collection. But there is a robust market in other vintage Saarinen work. Expect to see early Pedestal series pieces starting at $1,000, with vintage Womb chairs and ottomans ranging from less than $1,000 to more than $5,000. The latter high price notwithstanding, current Knoll production pieces are often much more expensive than their older counterparts.

To those, like us, who love brown wood and the skip of a craftsman’s chisel, one may well ask what wonders we find in molded plastic and chrome plating. We have come to believe that far more than silver-gray birch, or reinforced resin, or more than any particular style or form, it’s the stories behind the pieces that bring them to life.