Small but mighty. That’s how you might describe Kevin D. Murphy’s The Cathedral of Notre-Dame of Paris: A Quick Immersion, published late last year by Tibidabo. In fewer than two hundred five-by-eight-inch pages, Murphy, the Andrew W. Mellon Chair in the Humanities and professor and chair of the art history department at Vanderbilt University, brings to life the entire story of the renowned cathedral, including the devastating fire of April 2019. We asked him to update us on the current state of its restoration and to remind our readers of the place in American art of what is not only a landmark of French history and the Christian faith, but most importantly, Murphy says, is a “symbol of humanity.” He writes:

On April 15, 2019, the world watched, horrified, as Notre-Dame of Paris was engulfed in flames, its medieval wood roof structure reduced to cinders, and its landmark spire toppled. Soon, news images appeared of the stone vaults that had been damaged when the burned roof structure crashed down on them. The floor of the nave was heaped with the charred remains of the massive timbers.

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, public agencies and private groups and corporations from around the world rushed to offer financial support for a restoration and together committed hundreds of millions of Euros. President Emmanuel Macron of France declared that Notre-Dame would be restored quickly, hopefully by the time Paris hosts the 2024 Olympic Games.

It was one thing to resolve to restore the building; it was another to decide exactly how to do so. While much of the building is original to the twelfth century when the Gothic structure was begun on the site of an earlier church, some parts reflect later alterations or the major restoration that was begun in the mid-1840s under the direction of architects Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste Lassus. The spire that fell in 2019 was part of that restoration and had been completed around 1860 to replace the original, demolished spire. After the fire, various proposals for rebuilding in a contemporary form were made, including one by the designer Mathieu Lehanneur, who conceived of the spire as a three-hundred-foot gilt flame made of carbon fiber. Eventually, however, President Macron decreed that the new spire will re-create the one designed by Viollet-le-Duc.

The spire was but one of the parts of the cathedral that captured the eyes of artists from around the world, including the United States. An early American arrival at Notre-Dame following the completion of its restoration was Winslow Homer, who painted the cathedral during his nearly yearlong stay in Paris in 1867. Most of Homer’s known paintings from this French period were of rural subjects that reflected his interest in plein-air painting; his Gargoyles of Notre Dame is an exception. It shows some of the chimeras (sculpted grotesques, like gargoyles, but that do not serve as downspouts for rainwater) that were part of the restoration.

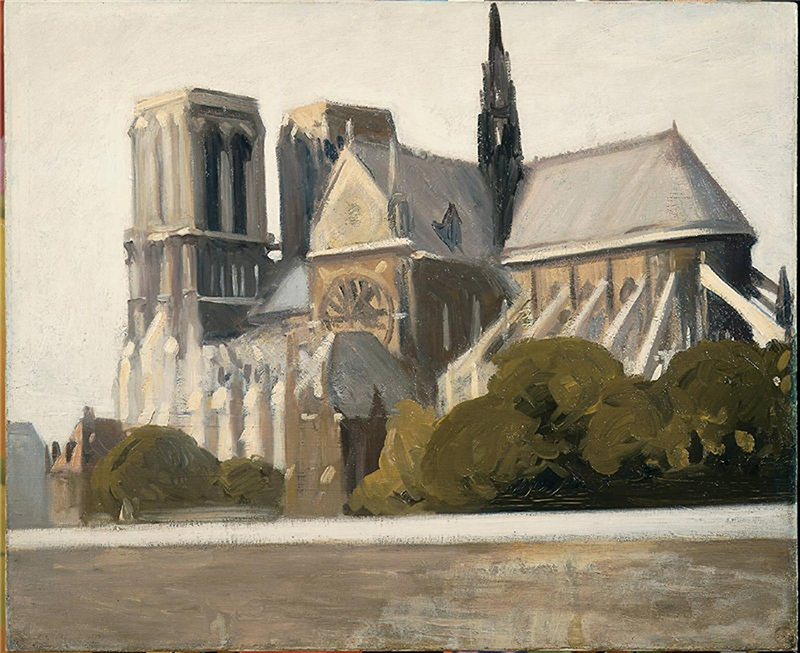

The cathedral became a staple of paintings of Paris in the impressionist and other modern French styles by Americans abroad. Childe Hassam showed it in characteristic impressionist fashion, emphasizing the clouds moving across the sky above the facade towers. Edward Hopper highlighted the flying buttresses around the nave and apse.

Reconstructing the spire with the wood from oak trees now being harvested around France is still a ways off. The initial “safety” phase of the restoration was long and laborious, and interrupted by the pandemic. When the spire does rise again, Notre- Dame will regain the appearance that has long attracted artists, not to mention visitors from around the world, to a building that is synonymous with France and its capital—and a beacon of humanity.