In her piece in this issue, Elizabeth “Penny” Stillinger writes that founding editor Homer Eaton Keyes set high standards for ANTIQUES from the very start. Articles were to be substantive and well written; quoting Mabel Munson Swan, she writes that Keyes was as “impatient of superficiality as he was of inaccuracy.” These are touchstones the magazine has lived by ever since, and one reason it has been able to do so is the nature of those who come to work here. I can say this with confidence because I have been with the magazine long enough to have worked with a great many of them. A love for the subject, curiosity, a sense of humor, and dedication to long hours, accuracy, and compromise (without the promise of much financial reward) have been the marks of so many of my colleagues over the years.

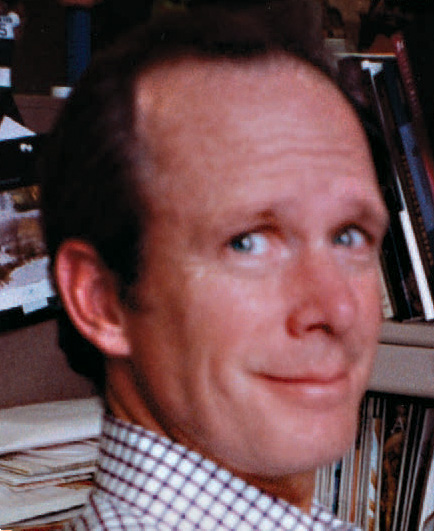

As it happens, I never worked directly with Penny, who served for several years as assistant to Alice Winchester, ANTIQUES’ second editor, and later as research editor before leaving to care for her two little girls; but she was the one who led me, searching for my first job after college, to ANTIQUES in 1972, mentioning to a neighbor, a friend of my parents, that there was an opening in the ad sales department. Ad sales was never going to be my forte, but Wendell Garrett, who had just taken over from Winchester as editor, agreed to talk to me anyway, and ended up offering me a temporary job when then–assistant editor Karen Barron called him to announce the birth of her baby, Austen Barron (now Bailly, currently chief curator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), and asked to start her maternity leave. The rest, as they say . . .

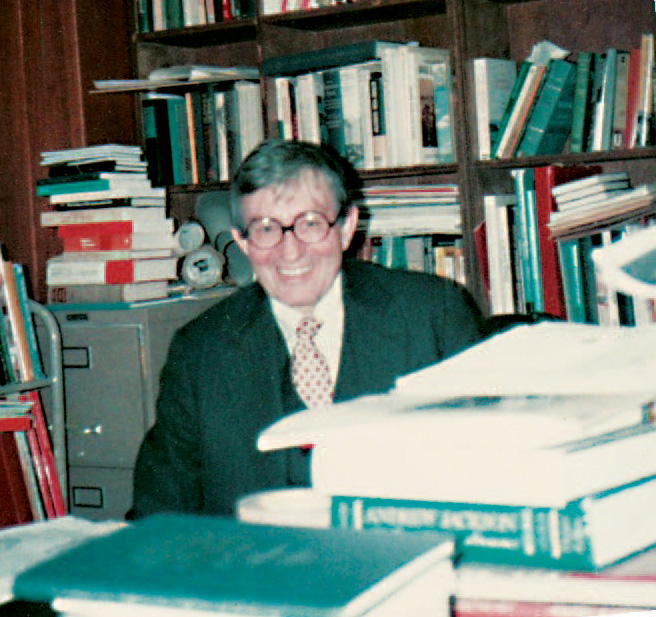

And that history, as it has always been for ANTIQUES, is the staff. In her years there, Penny told me, the senior editorial staff consisted of Winchester, Edith Gaines, Barbara Snow, and Ruth “Petey” Davidson. “Edith, Alice’s second-incommand, had a peppery personality and wit and specialized in glass. Barbara, our managing editor, was a lovely person with a specialty in historic preservation. Petey was our features editor and very knowledgeable about antiques She had gone to school in France and was our specialist, along with Alice, on all things French.” Working together led to friendships as well as the success of the magazine. “I remember having a group of staff members to dinner at our small floor-through in Brooklyn Heights—and this was before Brooklyn became the place to live and many people considered getting there a real chore. During the massive blackout of 1965 several of us who lived too far away to walk home enjoyed hours of conviviality at Barbara Snow’s apartment.”

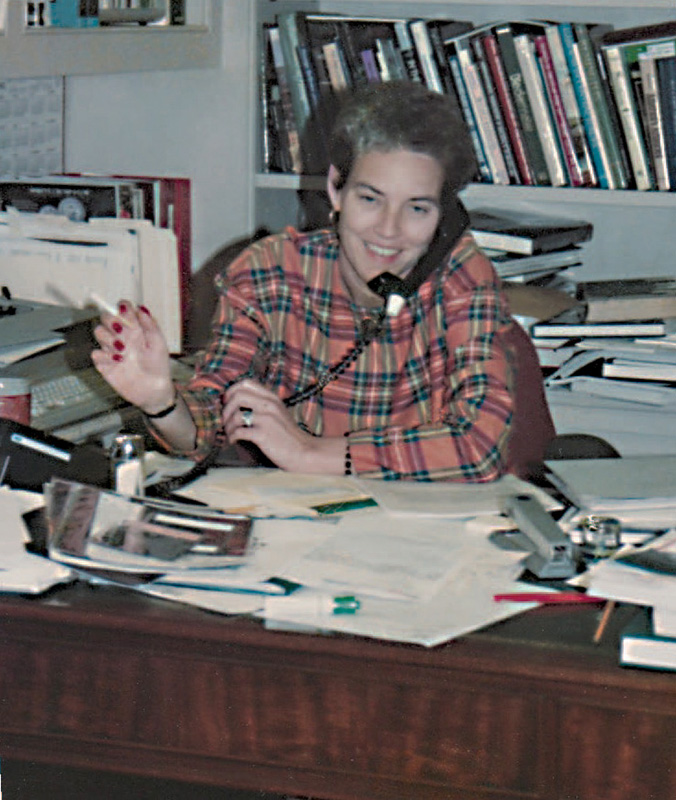

Despite advances in technology (when I started, we used typewriters, the office had a plug-in switchboard, the art department used slide rules to size photos, and I learned my first lessons in the decorative arts by typing Wendell’s letters from a Dictaphone), over the years, the sense of mutual support and friendship has endured. Wendell always invited the edit staff to share lunch in his book-filled office, and Allison Ledes, who succeeded him as editor in 1990, continued the tradition until her untimely death at fifty-three (sometimes we played hilarious games of Pictionary at lunch—and occasionally we gathered in the evening to watch Dallas). The communal lunches ended when the office was downsized—though they resumed (if perhaps out of necessity) after ANTIQUES became independent and we occupied two tiny rooms in a WeWork space. It bonds—as does sharing Twizzlers.

Of course, ANTIQUES is much more than the words on the page. The art directors—from Milton Glover to Martin Minerva—have been key to the magazine’s success, unfailingly actually reading the stories before doing a layout and good humoredly making changes when asked to do so—or even to do the whole thing all over again.

Onward to our next century, with thanks to all those, past and present, who hold Keyes’s standards dear.