The story of Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle series first unfolded in our pages in an article by Elizabeth Hutton Turner in January/February 2017. At the time, six of the series’ thirty panels had been lost. Three have now resurfaced, two since the launch of a traveling exhibition of the series now at the Seattle Art Museum. Both were recognized on the walls of Manhattan apartments by residents whose family members had acquired them some time ago, likely in the 1960s. We asked the exhibition curators to reflect on these two panels, as well as on those that are still missing, as we continue to reveal Lawrence’s telling of the American story.

Austen Barron Bailly, now at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, writes on Panel 16, There are combustibles in every State, which a spark might set fire to .—Washington, 26 December 1786:

Without even a photograph of the panel to go by, I had pictured bodies and weapons clashing in a fiery conflict—forms representing the federal army Daniel Shays tried to attack with his band of citizen-farmers. George Washington had foreshadowed Shays’ Rebellion in a letter written a month before the insurrection, the letter Lawrence excerpted for the title of the panel.

When the painting surfaced, I was moved by Lawrence’s apparent emphasis on the lingering anguish of an intense standoff. I heard echoes of shouting from still-open mouths. On the left, with bandaged heads, uniformed US troops stand erect, brandishing bayonets across a wedge-shaped space into the disheveled insurgents, flame-like locks of shaggy hair falling onto their harrowed faces. A stream of blood flows from a man in yellow boots, who stares at one bayonet blade as another pierces him, producing the gush that lands by the artist’s signature. Lawrence’s vision of a violent power struggle between fellow Americans is rife with uncertainty.

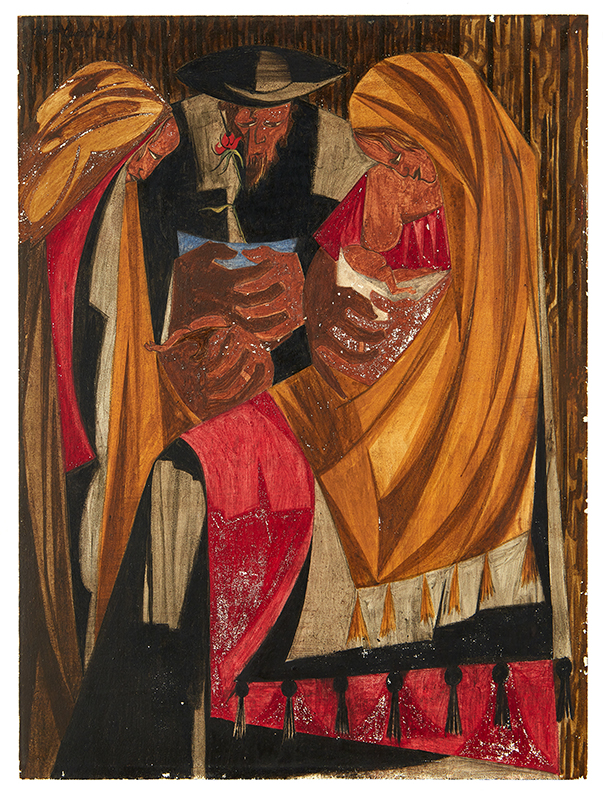

Lydia Gordon of the Peabody Essex Museum writes on Panel 28, Immigrants admitted from all countries: 1820 to 1840—115,773:

Using a black-and-white photo, we did our best to interpret the panel’s meaning by following the clues Lawrence painted on other panels. Seeing it in color, it became clear that Lawrence infused the panel with symbols of hope and new life. The woman draped in patterns of golden yellow looks down on the nursing infant swaddled in her arms. I was moved by Lawrence’s choice to emphasize nourishment, kin, and togetherness, yet also wondered at what cost were these people seeking freedom? Immigrants is the title caption, but on the back Lawrence wrote, “The Emigrants,” suggesting a desire for permanence in their new home. The middle figure clutches a potted rose—the national flower of the United States. Lawrence’s vision is that the arrival of all people, young and old, contributes to the expansion of America through their struggles and courage.

Elizabeth Hutton Turner, professor at the University of Virginia, concludes:

Lawrence’s images re-envision our past to reveal alternative ways of imagining what unites us and divides us in our shared histories as Americans. The missing Panel 14, Peace, last seen as a grainy photograph published in 1993, depicts a solitary idle canon that nearly fills the horizontal composition, situated in the series like a rest within measures of music. We have no image for the missing Panel 20, whose title, Spindles, suggests to me a long row of repeated shapes—spindles on a spinning mule. Panel 29, in a private collection in 2000, has since disappeared. Titled “A cent and a half a mile, a mile and a half an hour. . .,” it emphasizes the new equation of time, distance, and money applied to the labor force building the Erie Canal. One Black and two white laborers hoist a great beam above their heads in a painting that shares a palette of umbers and reds with Panel 28, perhaps alluding to them as immigrant workers.

Keep your eyes open. We hope the three missing panels will soon come to light and rejoin Lawrence’s epic Struggle.