The Magazine ANTIQUES | November 2008

Ernest L. Blumenschein (Fig. 2) is recognized for multiple and magnificent contributions to American art and culture. Many of his most laudable accomplishments, and they were legion, seem to counterpose one another-he was a virtuoso violinist and a skilled shortstop; his Beaux-Arts training as a painter sustained his allegiance to representational academic art, yet he championed modernism throughout his career; and he lived and thrived in New York and Paris while persistently longing for and ultimately becoming a full-time resident of the tiny village of Taos in northern New Mexico. Yet there was one dimension of his world that was enduringly unambiguous, and that was his own philosophical take on the favorite subject in his art, the American Indian.

Blumenschein was born in Pittsburgh and grew up in Dayton, Ohio. Because of his promising talents as a violinist, he earned a scholarship to attend the Cincinnati College of Music in 1892. Once there, however, he branched out, enrolling in drawing classes at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. A course in illustration taught by Fernand Lungren (1857-1932), an established New York illustrator of the period, was especially exciting for Blumenschein. It promised, in his words, “a chance to exercise my imagination,” and it launched his career as a pictorial artist.1 Lungren had just visited the West and had found success with frontier themes, including American Indian subjects, and this regional focus would help shape Blumenschein’s future as well.

Blumenschein moved to New York and attended classes at the Art Students League, studying under such worthies as Kenyon Cox (1856-1919), John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902), and J. Carroll Beckwith (1852-1917). But it was not until 1892, when he moved to Paris and began classes at the Académie Julian, that American Indians entered into the vocabulary of his art. One of his instructors, Jean Joseph Benjamin Constant (1845-1902), was especially interested in the exotic Arab cultures of North Africa, and surmised that Blumenschein might find similar inspiration in the Native American population. When Constant learned about a fascination Blumenschein had with James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, he urged him to explore the West for his own exotic motifs. In addition, Blumenschein befriended the naturalist illustrator and sculptor Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946), who had been a student at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the Art Students League, and the Académie Julian and maintained a studio in Paris. Seton shared an abiding interest in American Indian people and hosted parties at which the entertainment featured mock Indian dances, which Blumenschein enthusiastically attended.Returning to New York in 1896, Blumenschein embarked on a career as an illustrator. He was a particular favorite of McClure’s Magazine, whose editors hired him to embellish a variety of stories. Some of the assignments drew his attention westward, even when his physical presence was not required. Like many artists of his day, Blumenschein was initially exposed to the West through a visit to Madison Square Garden and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveling show, organized by William F. Cody (1846-1917). Blumenschein wrote a story for Harper’s Weekly about the experience, which he illustrated with a composite drawing that reflected the excitement of the scene and his genuine fascination with the American Indian members of the Wild West troupe (Fig. 3). He boasted rather flippantly that he knew “something of the Indian nature” before setting foot in the arena, but in fact he had little familiarity with the subject and his ephemeral exposure at the Cody extravaganza was something of a first encounter.2

His more mature and lasting take on native people came a few months later when he teamed up with the author and Indian rights advocate Hamlin Garland (1860-1940) to illustrate a historical account of “General Custer’s Last Fight as Seen by Two Moons.”3 Writing for McClure’s, Garland related the story of the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn from the perspective of the Northern Cheyenne leader Two Moons. Garland wanted to advance the notion that Indians were as much heroes in this saga as Anglo-Americans, a slant that was uncommon at the time. Blumenschein grasped the spirit of Garland’s argument, producing an illustration entitled We Circled All Round Him (Fig. 4) that elevated the valor and sacrifice of the American Indian warriors over Custer’s soldiers, who fight behind an obscuring cloud of dust in the distance.

Clearly, Blumenschein’s attitude toward native people had ceased to be glib and had become empathetic, respectful, and supportive, and his imagery began to earn him commissions specifically oriented toward a pro-Indian stance.4 Indeed, when in 1898 he joined forces with his former fellow Académie Julian student and then New York studio mate Bert G. Phillips (1868-1956) to spend a summer in Colorado, New Mexico, and Mexico, he went west intending to find American Indian people with whom he could establish a bond. He would later write that “I have had ever since my boyhood a great enthusiasm for Indian subjects and adventure.”5 Once in the impressive Taos Valley, these two passions converged serendipitously-the artists’ wagon broke down on a primitive country road and they discovered the local Pueblo people. Blumenschein would never be the same. Thereafter, the West, its potential for adventure, and its Indians possessed him. Even though he would soon return to New York, and then go to Paris for further study, achieve national recognition for his portraits of friends and family, and make a prosperous living as an illustrator of a wide variety of subjects, his heart remained in Taos.

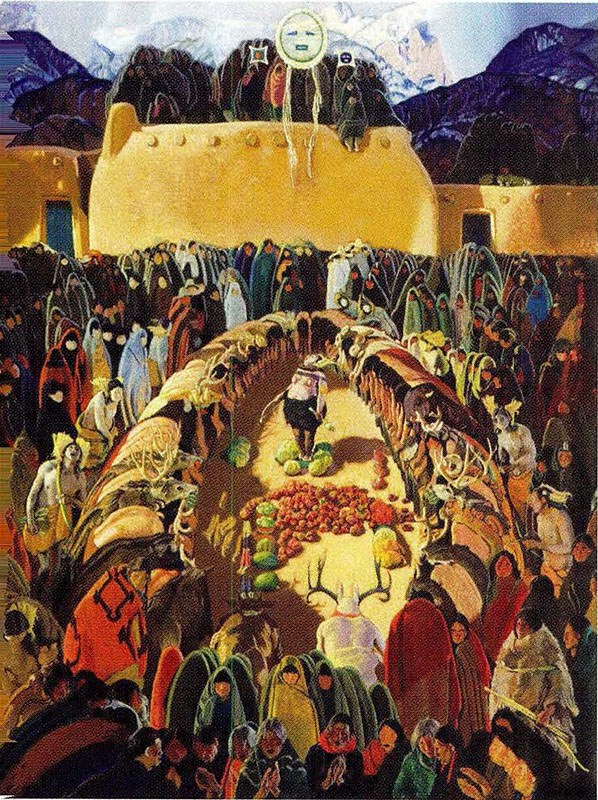

Blumenschein had been on assignment for Harper’s Weekly that summer, and shortly after his return to New York in the fall he completed a composite drawing summarizing his impressions of one of the Taos Pueblo’s most vibrant annual celebrations, San Geronimo Day (Fig. 5). The image was as documentary as those he had made behind the scenes at the Wild West show, but its message was more complex. In a clear pictorial record, he placed the striking mix of religious traditions, a Christian saint’s day and a Pueblo fall harvest ceremony, squarely before the public. Blumenschein found the cultural complexity of this union of customs to be fascinating. As a newspaper writer in the artist’s hometown of Dayton observed, he had revealed the Pueblos’ “character and life, which is seldom found in pictures of the Indian, a character which has been so much studied and is yet so little understood.”6 Blumenschein had occasion to return to Taos from time to time in the next few years. When he was there in the fall of 1901, he wrote his editor at Century Magazine, Alexander Wilson Drake (1843-1916), that being in Taos was like being in heaven:

I am wildly enthusiastic over my surroundings. I live in a little adobe town built up by a tiny stream which cuts through the desert and loses itself in the painted canyon of the Rio Grande. Everything about me is inspiring me to work; great mountain ranges that become as dear to one as a friend, Indians that are still real and themselves…self-supporting, clean minded people who still have their old customs…, landscapes big and beautiful, colored cañons with happy vigorous streams, deserts reflecting a vast sky-and you feel yourself a part of it all, and live with it and are never alone.7

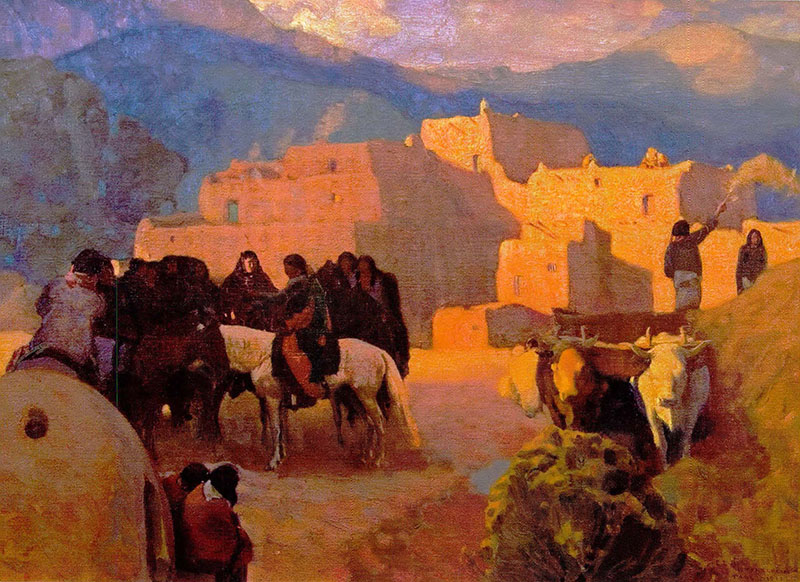

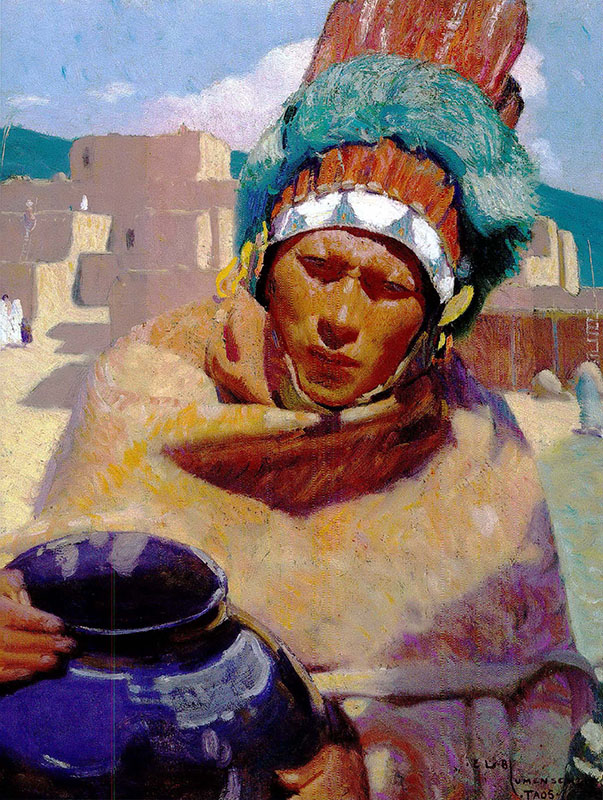

After he and his new wife, the artist Mary Shepard Greene (1869-1958), returned from Paris and settled in New York in 1909, Blumenschein began to frequent New Mexico on his own every summer. He went there to paint rather than find subjects for illustrations, and he made a special effort to focus on painting the Pueblo people. His goals in this were multiple. First, he wanted to explore New Mexico’s indigenous people using lessons he had recently learned in Paris about effecting tonal harmonies with color and recounting a poetic vision of the world around him. The results may be seen in his glowing pictorial tribute Evening at Pueblo of Taos (Fig. 1), which was commissioned by the Santa Fe Railroad in 1913 for promotional purposes. Containing some details from his illustration of San Geronimo Day, this evocation of Pueblo life, suffused with elegance and quietude, acknowledges the theories of his latest French mentor, Émile René Ménard (1862-1930), who had taught him the use of a warm harmonious palette. It also reflects his patron’s desire to make Taos and the Southwest a place of promise for tourists, a place that is fleeting, exotic, inviting, accessible, and safe.The artist also wanted to explore, beyond the influences of the Académie Julian, some of the striking post-impressionist color theories to which he had been exposed in Paris. He had been especially impressed with the brilliant hues in paintings by Henri Matisse (1869-1954) that he had seen at the apartment of Leo Stein (1872-1947) and his sister Gertrude (1874-1946) in 1907. Now he applied that brilliance to the western scene in another painting for the railroad, Taos Indian Holding a Water Jar (Fig. 6). While the theme of this work suggests an artistic commoditization of native people and their crafts, in spirit it exalts them.

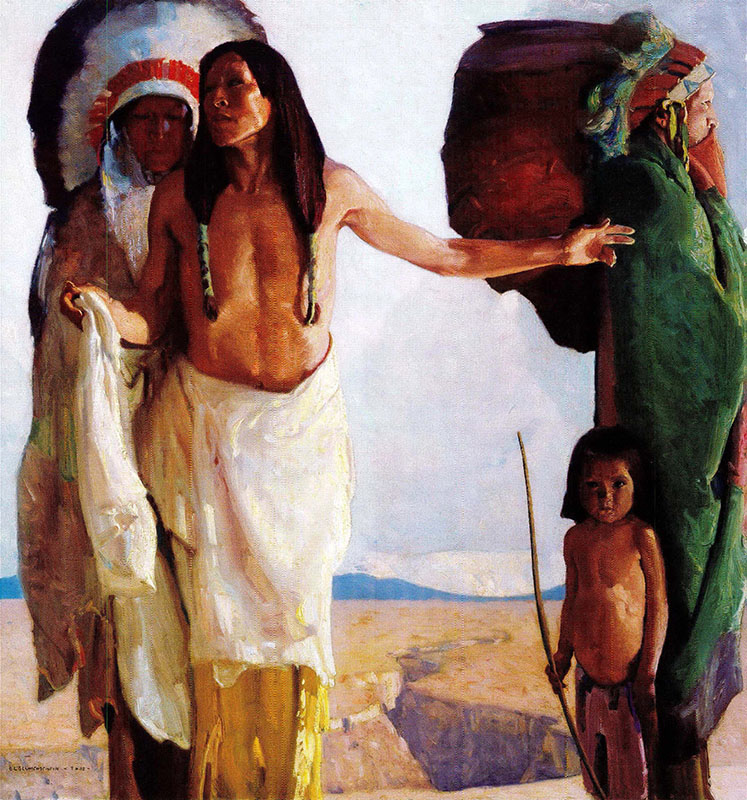

Large exhibition works that resulted from Blumenschein’s summers in Taos, such as The Peacemaker of 1913 (Fig. 7), suggest that he wanted his audience to respond to formal elements as much as to his narrative messages. Here he idealized the American Indian, posing the central figure as the Greek god Apollo and employing a muted palette that would conform to a classical mode. He also strove to achieve a pure, decorative effect, and art critics soon recognized that with such paintings he had found an aesthetic “field rich in possibilities.”8 The painting is also laden with symbolism, reflecting everything from tribal resistance to United States government Indian policy, to the imminent war in Europe.

By 1915 Blumenschein’s and Phillips’s seventeen-year-old dream of establishing an artist colony in Taos had come true, and a formal organization, the Taos Society of Artists, was formed. The group, including Joseph Henry Sharp, William Herbert Dunton, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and Eanger Irving Couse, prepared traveling exhibitions of paintings by member artists that promoted the Southwest around the country. About 1918, even though World War I was interfering with much of their enterprise, Blumenschein painted one of his most beautiful and compelling works, Portrait of Albedia (Fig. 8). It is not simply an arresting study of character, but also an exquisite interplay of line and mass with a rich saturated palette. Though more tightly handled, it was confused by critics at the time with similar American Indian portraits by Robert Henri (1865-1929).

After the war, in 1920 the Blumenschein family-Ernest, Mary, and their daughter Helen (1909-1975)-moved from Brooklyn to Taos full time. It was, the artist said, “the great decision of our lives.”9 He later wrote that the American Indian was his prime impetus for transporting “our Paris furniture, my frontier-fearing wife and one small daughter to this new life so far removed from all the comforts and attractions of great cities.”10 Taos would not have plumbing and electrical service until 1930.

Thanks to an inheritance Mary had received, Blumenschein embarked on what he called “the principal stage of my ambition.” At this point, he said, he:

refused all commercial work and took a chance on painting the kind of pictures it was in me to do. The general public did not care for my interpretation of Taos. The people of New Mexico, too, wanted something more sentimental and picturesque; but the critics and artists back in Chicago and New York were kind to my efforts and…that was the audience I was playing for.11

is masterpiece of 1920, Star Road and White Sun (Fig. 9), was exemplary of his awakened aspiration. It was as much a paean to cultural preservation and aesthetic invention as it was a powerful portrait of his Pueblo model Star Road, who was also his friend and his family’s handyman. Many of Blumenschein’s fellow Taos artists had continued to idealize the Indians, creating stereotypes of poetic, timeless people who lived in special harmony with nature. In Blumenschein’s rendition, Star Road has his own identity, proudly proclaiming his emergence as a representative of a new generation of Indian people.Blumenschein recognized the tensions inherent in combining Anglo-American, Hispanic, and native cultures in one place. His art spoke eloquently about these strains on real people, such as Jim Romero, another Pueblo friend and frequent fishing and camping companion, who suffered the uncertainties presented by conflicting spiritual ideologies. Using visual irony, in his 1921 painting Superstition

(Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma) Blumenschein makes the point that one person’s religion may be viewed by another as superstition. From the neck of the Tewa wedding vase depicted in the work, a pottery form that was developed for the tourist trade, comes a dancer symbolizing traditional Indian ceremonies and a sheaf of wheat connoting the Christian population of God’s kingdom. Romero, as a symbol of his people, seems stupefied by the pressure to choose one over the other.

When Indians were allowed to practice their own religious ceremonies unfettered by church or government influences, Blumenschein was prepared to lavish on the scenes an unequivocal mantel of dignity and splendor. Moon, Morning Star and Evening Star (Fig. 11) reveals a spiritual world that is purposeful and highly ordered, pulsing with rhythm and life, and profoundly joyful. He painted it at a time when the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs was making concerted attempts to outlaw native dancing and religious ceremonies. The canvas, along with a host of similar efforts from Taos’s intellectual and creative community, helped to engender resistance so powerful and widespread that the government program succumbed to public pressure.

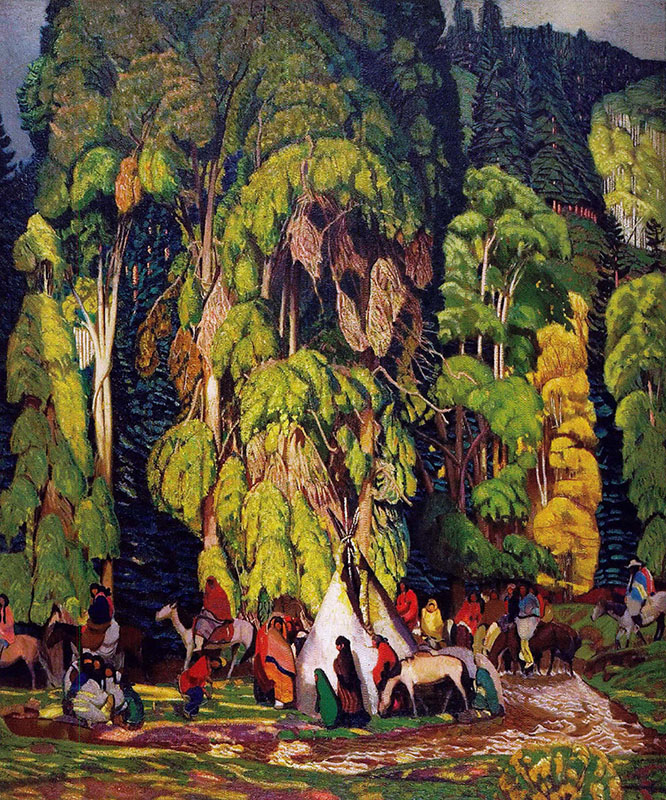

By the mid-1920s, American art critics were tiring of Indians in art. “The Indian, as a painter’s subject, has gone a bit stale,” wrote one observer in Art News.12 Blumenschein, ever mindful of his need for national critical approbation, quickly moved in a new direction. However, he did not abandon Indians in his paintings; he simply made them a fundamental part of the larger scene, the New Mexico landscape. Thus, in Landscape with Indian Camp (Fig. 10), with its exhilarating swirl of light and form, he integrates the Indians into the pulse of nature, making them a crucial figurative element in the otherwise nearly abstract design. This was a solution that would serve him well in future years.

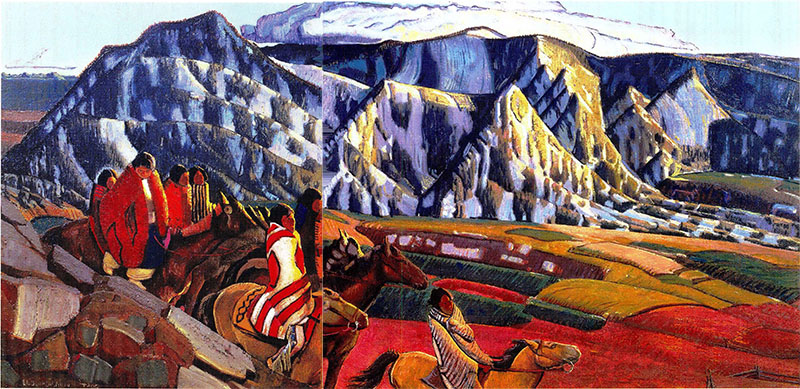

In a work from the 1930s, Indians in the Mountains (Fig. 12), he utilized the same highly formalized design construction, tying the patterns of the blanketed Indians into the geomorphic facets of the mountains behind them. Unlike works such as Star Road and White Sun and Moon, Morning Star and Evening Star, this was far removed from social commentary. Blumenschein, in his later paintings, was concerned strictly with perfecting design in which light, line, and colors were orchestrated into a symphony of pictorial genius. His imagery continued to serve American art with its inventiveness and excellence, and elevate American Indians with reverence and uncompromised empathy for them and their culture as worthy of preservation.

An exhibition of Blumenschein’s work entitled In Contemporary Rhythm: The Art of Ernest L. Blumenschein will be on view at the Denver Art Museum from November 8 to February 8, 2009; and at the Phoenix Art Museum from March 15 to June 15, 2009. It was also organized by the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, where it was shown through September. The accompanying catalogue was written by Peter H. Hassrick and Elizabeth J. Cunningham, who are co-curators of the exhibition.

1 Ernest L. Blumenschein interview with Dewitt M. Lockman, transcript, 1927, p. 6, Dewitt Lockman Papers, New-York Historical Society, New York, copy in the Nita Stewart Haley Memorial Library, Midland, Texas. 2 Ernest L. Blumenschein, “Behind the Scenes at a ‘Wild West’ Show,” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 42, no. 2158 (April 30, 1898), p. 422. 3 Hamlin Garland, “General Custer’s Last Fight as Seen by Two Moons,” McClure’s Magazine, vol. 11, no. 5 (September 1898), pp. 443-445. 4 See, for example, his illustration Wards of the Nation-Their First Vacation from School on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, vol. 43, no. 2217 (June 17, 1899); his illustrations for Hamlin Garland, “Sitting Bull’s Defiance,” McClure’s Magazine, vol. 10, no. 1 (November 1902); and his plates in Charles A. Eastman, Indian Boyhood (McClure, Phillips, and Company, New York, 1902). 5 Lockman interview, p. 12. 6 “Ernest L. Blumenschein,” Dayton Daily Journal, January 9, 1899. 7 Ernest L. Blumenschein to Alexander Wilson Drake, September 15, 1901, Blumenschein Papers, Archives of American Art, Washington. 8 Ernest Peixotto, “The Field of Art,” Scribner’s Magazine, vol. 54, no. 2 (1913), p. 258. 9 Ernest L. Blumenschein interview with Reginald Fisher, 1948, Blumenschein Papers. 10 Ernest L. Blumenschein, “Ernest Leonard Blumenschein,” typewritten autobiographical sketch, c. 1930, Ted Schwarz Papers, Special Collections Library, Arizona State University, Tempe. 11 Ibid. 12 Quoted in “The Artist Colony Corner,” Taos Valley News, March 15, 1924.

PETER H. HASSRICK is the director of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum.