Wine comes in at the mouth / And love comes in at the eye,” wrote poet William Butler Yeats. “That’s all we shall know for truth / Before we grow old and die.” Whether appreciated as a soothing elixir, or shunned as the slippery slope to perdition, wine is rarely perceived as merely a beverage. Even when sipped as part of a humble meal, it asks our consideration in a way that water never could. Be it a garnet-hued Barolo, a honey-colored Sauternes, or an everyday, ruby-red Côtes du Rhône, wine just seems to promise so much, whether that’s simply a nicer afternoon than one expected, or the possibility of love.

Wine is so central to the physiological and psychic thirst of humankind, it is no wonder that the grape has figured extensively in art. With In Vino Veritas (In Wine, Truth), the Cleveland Museum of Art dips into its extensive collection of prints and drawings to explore how this potable was depicted in European art from 1450 to 1800. “Once you start to look at museum collections, it is striking how many objects relate to making or drinking wine and all that goes with it,” observes Emily J. Peters, curator of prints and drawings.

“As a specialist in early modern prints and drawings, I have been wanting to show some of our prints by Andrea Mantegna for quite some time, as well as some of what I consider the more humorous prints and drawings in the collection, those depicting Bacchanalia and other wine-fueled festivities.

And I have enjoyed selecting a group of drinking glasses, as well as chalices and kiddush cups, to display in our galleries.” Peters is especially pleased to acknowledge the significance of wine in Jewish ritual and includes in the exhibition four very rare embroidered panels that have not been on view at the CMA for decades. Sewn in Venice in the sixteenth or seventeenth century and most likely remnants of a tablecloth for the Passover seder, they depict scenes from the Exodus story.

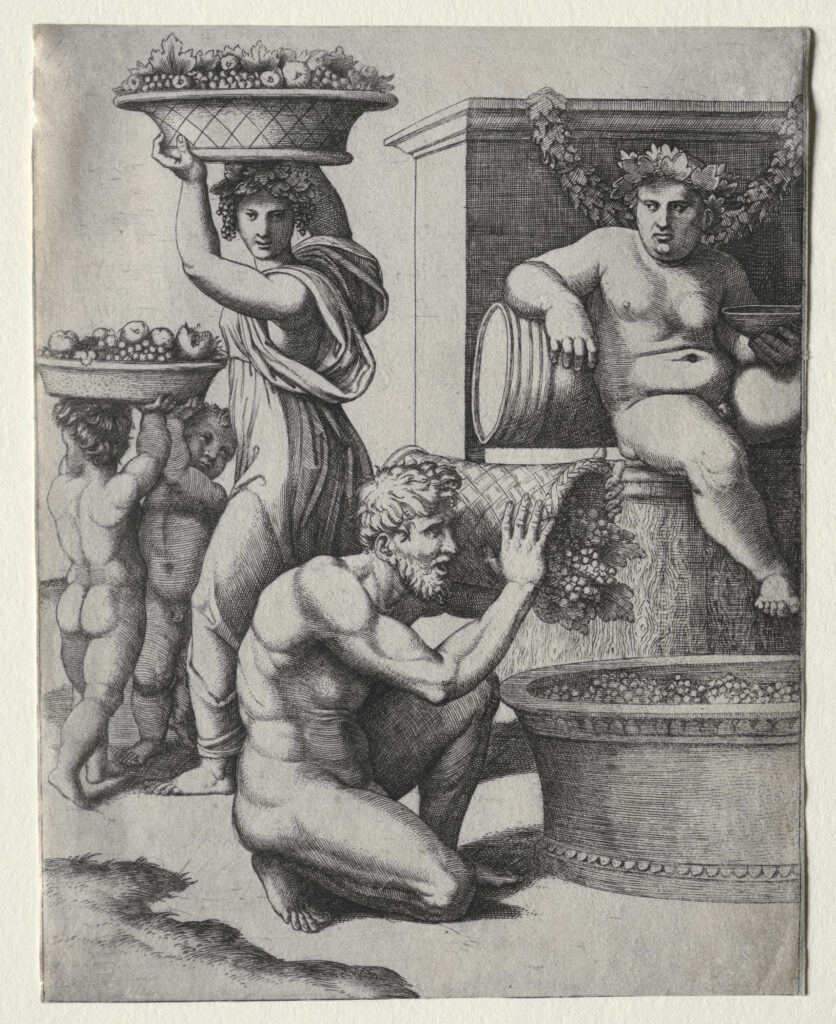

The exhibition, which opens September 7, is arranged along sacred and profane lines, with abandon and Bacchanalia coursing through one gallery, the devotional and biblical standing resolute in another. Taken together, one is reminded that the distance between pleasurable expectation and regrettable dissipation is often brief. In the engraving Bacchanal with a Wine Vat (1470–1780), Mantegna depicts a self-possessed Bacchus surrounded by those in their cups.

In Jusepe de Ribera’s Silenus (1628), this mentor to Bacchus—whose wisdom was attributed to his copious wine consumption—appears utterly blotto, his grotesque belly and man boobs seemingly as fluid as the wine he has so clearly been downing.

“In contrast to these Renaissance works, the eighteenth century brought a more courtly approach to the culture and mythology of wine in France,” Peters says. “Artists portrayed Bacchus and Bacchanalia, but increasingly emphasized images of satyrs, maenads, and woodland creatures, all associated with revelry, fertility, and nature. Jean-Honoré Fragonard created four etchings shortly after returning to Paris from Italy that feature the followers of Bacchus, but the wine god does not make an appearance. Instead, Fragonard highlighted the playfully erotic frolics, conflicts, even family life of a group of bacchantes.”

The English, of course, have rarely seen hedonism as harmless. In 1864 (when even the French must have found the long-gone Fragonard’s confections a bit too sweet), George Cruikshank and Charles Mottram produced The Drinking Customs of Society or Worship of Bacchus, a steel engraving aimed squarely at the nation’s fondness for the bottle. Riffing on a Roman Bacchanalia, it comprises a dizzying vortex of individuals and tableaux—from a family raising a glass contentedly around a dining table to disheveled women stumbling in the streets and scenes that wouldn’t be out of place in Saltburn.

Today, the jury is still out on the risks of wine drinking. No matter what science concludes, many will concur with Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who, in his monumental Physiology of Taste, wrote, “I’m tempted to put the desire for fermented liquors, which is unknown to animals, beside the fear of the future, which is equally foreign to them, and to regard both these manifestations as distinctive attributes of man, that masterpiece of the last sublunary revolution.”

—Thomas Connors

In Vino Veritas (In Wine, Truth) • Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio • September 7 to January 11, 2026 • clevelandart.org