Crispus Attucks—killed in the Boston Massacre—may have been a runaway slave. He may have been of mixed race. But there is no doubt he went down that day in 1770. Although deemed the leader of the men who taunted the British, no man of color appears in Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the confrontation; it seems a nineteenth-century drawing by William L. Champney (active 1850–1857) was the first in which one does. The narrative of African American life is, of course, riddled with such oversights, omissions, and erasures—voids that provoke historians and perplex the public. In the art of the early republic, painter Joshua Johnson likewise remains a figure whose biography is blurry, but whose skill and success constitute a significant achievement. With Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, Maryland, offers the first in-depth look at the artist since a major show in 1987.

The earliest manifestations of conventional artistic practice by Black individuals in America includes a portrait of the enslaved Boston poet Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784) attributed to a fellow enslaved Bostonian, Scipio Moorhead. Neptune Thurston, a Newport cooper who sketched on his barrels, is said to have influenced the young Gilbert Stuart. But between either a dearth of documentation or art history’s neglect (often both), even later painters such as landscapists Robert Scott Duncanson (1821–1872) and Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828–1901) were slow to be admitted into the accepted roster of American artists. As educator and activist Margaret Just Butcher noted in The Negro in American Culture (drawn from the final work of theorist and critic Alain Locke), the world “had the notion that for a Negro to aspire to the fine arts was ridiculous. Before 1885, any man or woman with artistic talent and ambition confronted an almost impossible barrier.”1

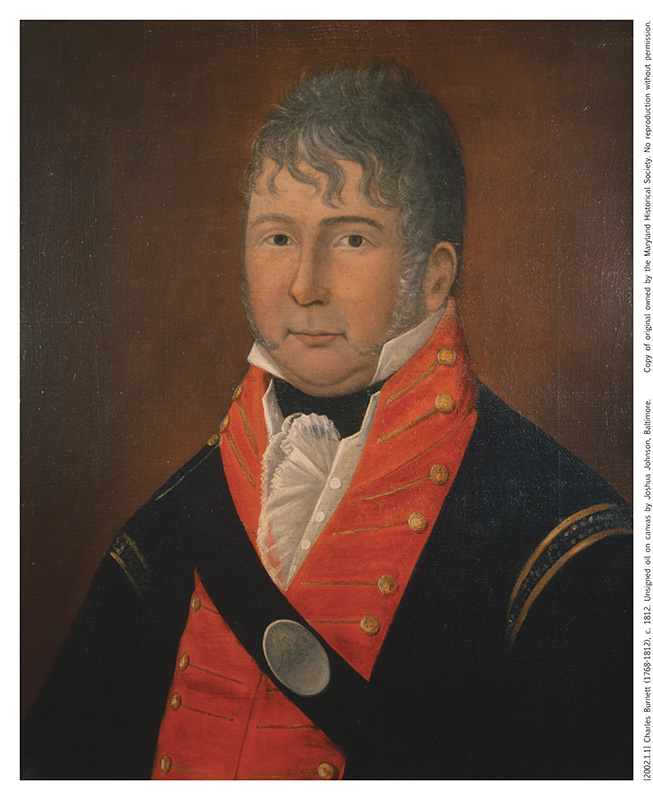

Scholars and historians have been doing their best for decades to understand Johnson’s life and career. Not surprisingly, those efforts have required not only stylistic analysis of the work itself but an investigation of the status of Black Americans and the singular position of the Black artist over time. Johnson was born enslaved in rural Baltimore County, Maryland, to a woman owned by a William Wheeler and a white man, George Johnston (in time, the “t” disappeared from the artist’s surname). While Johnson was still a child, his father bought him from Wheeler. He apprenticed the boy to a blacksmith, and later secured his manumission. Johnson married in the mid-1780s, became a father, and, by 1795, began advertising himself as a portraitist.

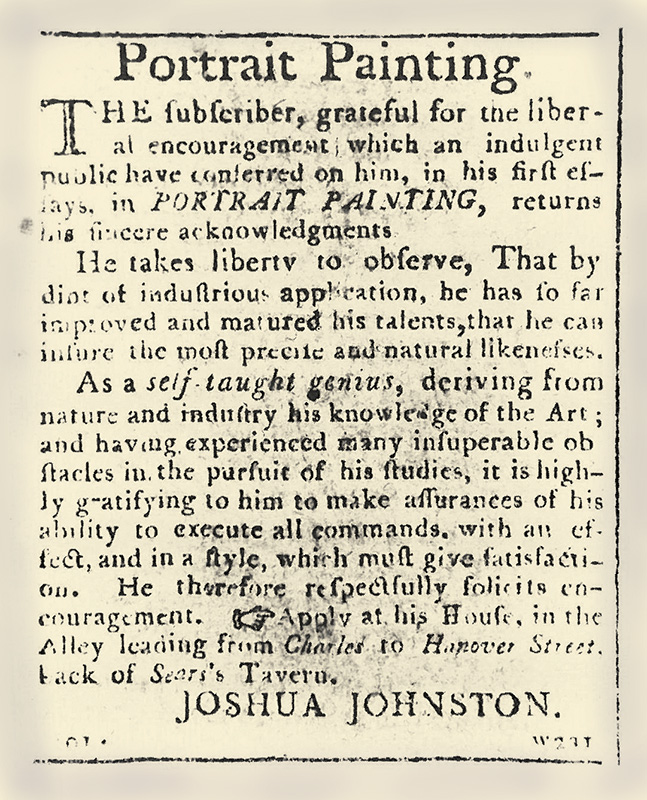

In a 1798 newspaper ad promoting his talents, Johnson lauded his own “industrious application” and deemed himself a “self-taught genius” (Fig. 10). The nurturing of Johnson’s ability (along with his relation ship to his sitters, his status as a freeman in a slaveholding state, and his relationship to other people of color) has long been a matter of speculation. Comparisons have been made to the work of Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822). Orphaned at age ten and raised in Philadelphia by his uncle Charles Willson Peale, Polk painted in Baltimore for a few years starting in 1791, and in 1793 and 1794 he operated an art school in the city, but there is no proof that Johnson trained there. As curator Daniel Fulco suggests in his essay for the current exhibition, Johnson may have developed his visual literacy in part with visits to the Peale Museum in Baltimore (which displayed works by several members of that artistic family) and through exposure to engravings made of oil portraits. As for learning the mechanics of drawing and painting, Johnson may have gleaned those from Baltimore’s furniture decorators, as Lynda Roscoe Hartigan (now the director of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts) observed in the catalogue for her 1985 exhibition Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America at the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum). “His various addresses . . . were located in the section known for its fancy-and-painted chair makers,” she noted. “Portraitists of the period often supported themselves as furniture decorators and it is possible, although not conclusive, that Johnson also practiced the craft.”2

Johnson scholarship commenced in earnest with the efforts of Jacob Hall Pleasants, a physician with an avid interest in Maryland history. In 1942 he published Joshua Johnston, the First American Negro Portrait Painter. Artists of the day, particularly limners, did not always sign their work and after examining paintings attributed to Polk and his kinsmen Charles and Rembrandt Peale, among others, Pleasants posited these as the work of Johnson. A sharper sense of attribution came in 1976, when Rebecca Myring Everette (Mrs. Thomas Everette) and Her Children (Fig. 4) was bequeathed to the Maryland Historical Society (now the Maryland Center for History and Culture). The picture’s provenance included Mrs. Everette’s will, in which she stated that the large family portrait was “painted by J Johnson in 1818.”3

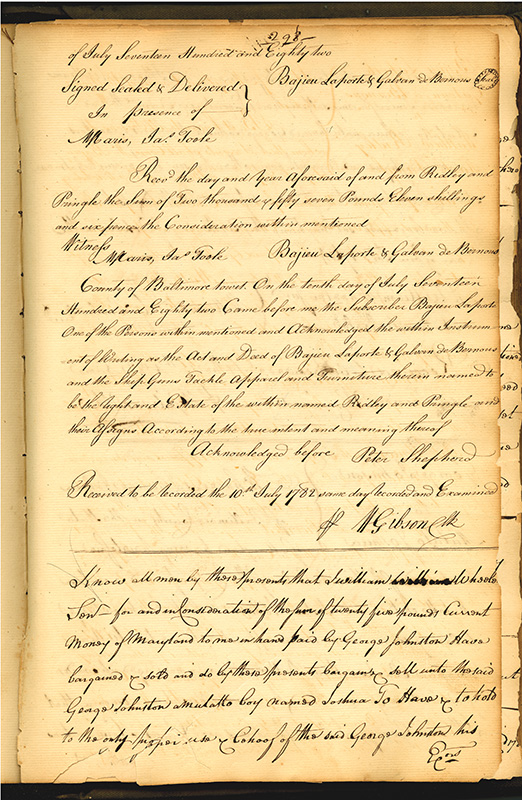

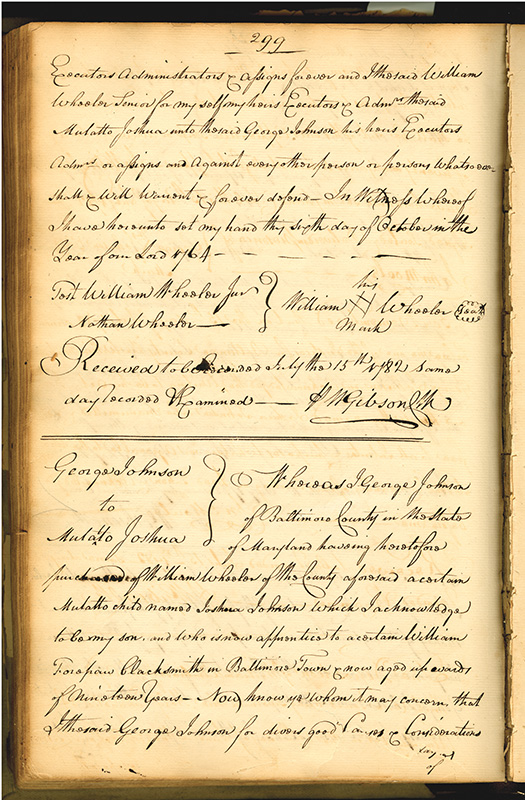

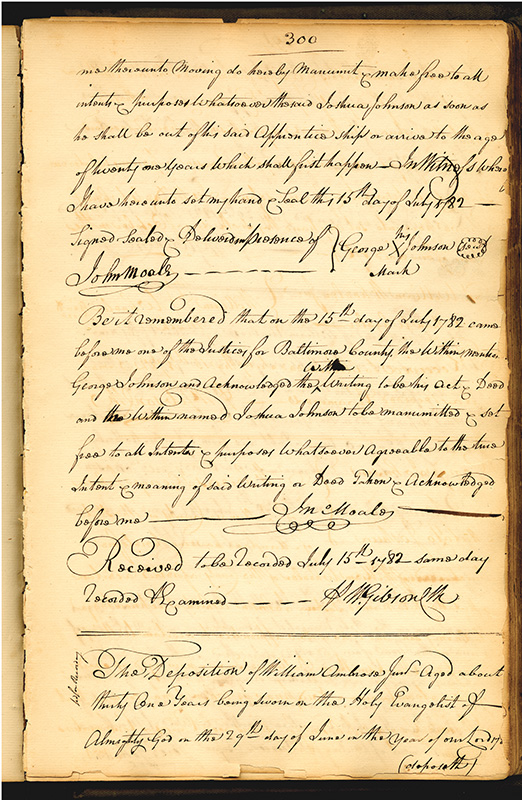

In 1987 the Maryland Historical Society and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center at Colonial Williamsburg presented Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter. Although Pleasants had identified Johnson as Black decades earlier, questions of his race remained. In A History of African-American Artists, published in 1993, Romare Bearden offered a substantive essay rehearsing the narrative of the artist’s racial identity, including the conclusions articulated by Carolyn J. Weekley, who led the research for the 1987 show. “During the last fifty years it has been increasingly accepted that Joshua Johnston was indeed an African-American,” he wrote. “We believe that to be the case, but belief is not proof.”4 Proof arrived in 1996, when Jennifer Bryan and Robert Torchia researched Baltimore County court chattel records housed at the Maryland Historical Society. These documents included the 1794 bill of sale transferring ownership of the young Joshua from William Wheeler to George Johnston and a later manumission record, in which Johnston acknowledged that the young man was his son (Fig. 7).

An appetite for portraits seems to have emerged much later in Maryland than elsewhere in the colonies. Justus Engelhardt Kühn (d. 1717) and Gustavus Hesselius (1682–1755) both worked there in the early eighteenth century, but as art historian Wayne Craven surmised in Colonial Portraiture in America, “Unless additional works or documentation comes to light, we can only conclude that Maryland was not a rich center for the creation of portraits before 1750.”5 As fortunes began to rise mid-century with the milling and exporting of flour, Baltimore’s civic leaders and merchant class took increasingly to the habit of sitting. Johnson’s patrons were not necessarily la crème de la crème, but, rather, upper middle-class residents. “The only elite individual he paints, in my view, is John Carroll, the first Catholic bishop in the United States [Fig. 3],” Fulco says. “He was of the aristocracy, if you want to call it that, because he descended from the Carroll family of wealthy planters. But the majority of Johnson’s sitters were people like Archibald Dobbin, a Baltimore customs house inspector—people whose tastes were more down-to-earth, who wanted something that spoke to their middle-class values. That’s the niche that Johnson occupies.”

Although Johnson’s early work is executed in the flat, unmodeled mode common to many early American portraits—especially those produced by itinerant limners—in time the artist mastered a telling compositional manner and a facility with detail. “For me, Joshua Johnson is distinguished from other limners working in other parts of America in that he really pays attention to the jewelry and props,” Fulco says. “Other limners tended to do this very flatly, even Ammi Phillips and William Matthew Prior.”

Johnson’s depictions of children—often young girls alone in a natural setting—demonstrate his grasp of allegory with the incorporation of such symbolic imagery as fruit, flowers, and butterflies. And in some paintings, one spies in the seemingly stern faces a subtle expressiveness. There’s a restrained but unmistakable vitality to the countenance of the figure rendered in Woman of the Shure Family. “At first I thought Johnson was kind of stiff,” Fulco says, “but when I started comparing him to other mid- Atlantic and New England limners from the same period, I was really surprised by the degree of refinement. The images by contemporaries just north in Pennsylvania, such as Jacob Frymire, are much more wooden, almost marionette-like.”

In reviewing the trajectory of Johnson scholarship— from the foundational efforts of Pleasants, through the broader examinations of African American artists by the renowned Baltimore-born art historian James Porter and his protégé, the late artist, curator, and scholar David Driskell (who, in 1976, organized the landmark traveling exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750–1950), Fulco sees Portraitist of Early American Baltimore as a re-orientation of sorts, away from the artist’s life and toward his work. While Fulco and his colleagues (David Taft Terry, professor of history at Morgan State University, and Mark B. Letzer, president and CEO of the Maryland Center for History and Culture) fully examine Johnson’s biography and the social and political context of his times, Fulco expresses a determination to fully appreciate the talent of the man. “His portraiture shows some of the untrained conventions of folk portraiture, but it also has a refinement,” he says. “It’s urbane. Even though we do not think he was formally trained, Johnson had access to engravings, access perhaps to other portraits in his patrons’ homes, he makes copies, he studies previous art historical conventions and may have even had access to illustrated books of iconography and symbolism. He’s part of late colonial, early Federal portraiture, but not the Peale branch, not the Gilbert Stuart branch, not the John Singleton Copley branch. He really is an independent.”

Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore is on view at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, Maryland, to October 24.

1 Margaret Just Butcher, The Negro in American Culture, 2nd ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), p. 214 2 Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, Sharing Traditions, Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), p. 41, citing American Folk Portraits: Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, ed. Beatrix T. Rumford (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1981), p. 133. 3Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, ed. Daniel Fulco, with David Taft Terry and Mark B. Letzer (Hagerstown, MD: Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, 2021), p. 75. 4 Romare Bearden, “The Question of Joshua Johnston,” in Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, A History of African-American Artists from 1792 to the Present (New York: Pantheon, 1993), p. 3. 5 Wayne Craven, Colonial American Portraiture: The Economic, Religious, Social, Cultural, Philosophical, Scientific, and Aesthetic Foundations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 246.

THOMAS CONNORS is a Chicago-based arts writer.