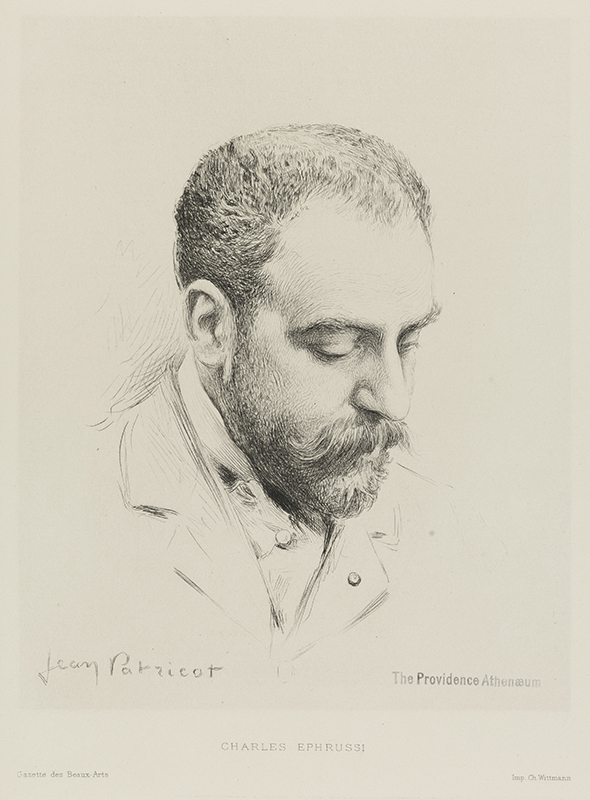

Edmund de Waal’s elegant and much praised family memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes, is now an art and antiques exhibition, crossing from the pages of literature to the walls of the Jewish Museum in New York. The show, which bears the same name as de Waal’s 2010 book, is grounded in the now-famous group of old netsuke—small ivory, wood, or lacquer Japanese sculptures—acquired in the 1870s by Charles Ephrussi (Fig. 7), de Waal’s great-great-uncle—a connoisseur, writer, patron of the arts, and man on the scene in the avant-garde Paris of the last decades of the nineteenth century.

The precious little netsuke propel the story of the immensely rich Ephrussi family from Odessa to Vienna, Paris, and Tokyo, through booms, busts, falls of empire, and the Holocaust, to a point where a hidden past meets the present. The more than four hundred objects in the New York show are arranged with a panache unusual for a museum by Diller Scofidio and Renfro, the architecture and design impresarios.

The exhibition The Hare with Amber Eyes is both scholarly and aesthetically rich. Chronologically, it covers more than 150 years, five generations, and half a dozen countries. It’s arranged in six galleries within what was once the Gilded Age mansion of New York’s Warburg family and is now the museum.

It starts with a wunderkammer. It’s a visually impressive way to introduce the scope of the art that different Ephrussis owned, and to present a family who’s who. They began to make their fortune in Odessa in the 1840s, when Ignaz Ephrussi cornered the market in Ukrainian wheat and became known as the King of Grain. Vienna, the capital of the empire at the heart of Europe, a city and a nation that looked both east and west, was soon seen by Ignaz as the place a conglomerate and a family of consequence ought to be. A wunderkammer is where a collector displays rarities and curiosities, usually from many places and assembled over time. De Waal, best known as an English ceramist before he wrote the book, knew both something and next-to-nothing about his Ephrussi family roots. Over two years of travel and deep research, he assembled a story that’s itself packed with rarities and curiosities.

A gallery titled “Paris” presents the life of Charles Ephrussi: smart, rich, a bon vivant, and the youngest male member of the branch of the family sent to Paris to run its business interests there. As a younger son, his comings and goings were unfettered by business. He was free to pursue his own interests. These were mostly cultural. Charles acquired the netsuke early in his collecting career when, smitten by the Japonisme craze, he bought in one fell swoop 264 exquisitely carved examples. They were once used as toggles for high-end kimonos (see “Small Wonders,” p. 91), but, in Charles’s time and place, were seen as freestanding sculptures and collectible.

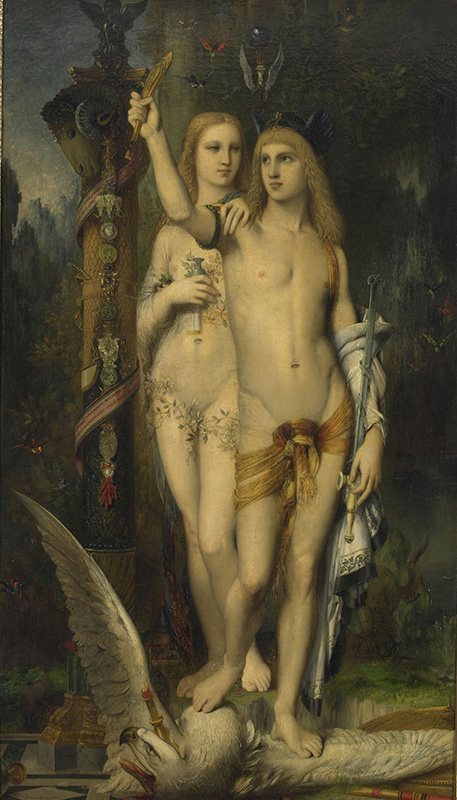

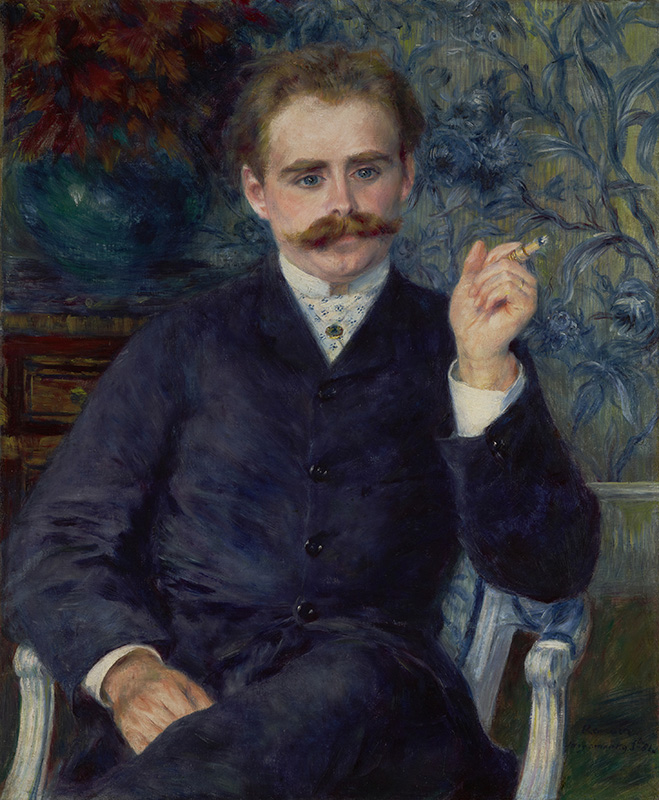

Charles’s interest in Japonisme was hit-and-run, a youthful impulse and splurge. As a curious but unformed aesthete, wasn’t he supposed to go with the latest luxury flow? His real passion, we learn, was impressionism, and, soon, art criticism. There’s a lovely Claude Monet painting in the show and portraits by Berthe Morisot (Fig. 2) and Pierre- Auguste Renoir (Figs. 6, 9). Charles knew all of the major impressionists. His relationships are a big part of the exhibition. He collected Morisot’s work, and enthused about her paintings in the magazine he edited, the Gazette des Beaux-Arts. For Renoir, he was a patron who introduced him to other patrons, such as the composer Albert Cahen. For Charles, Renoir was part servant, part acolyte—the artist even depicted Ephrussi in his famed society painting Luncheon of the Boating Party (Fig. 6). (Charles is the overdressed gent wearing a top hat.) Degas was a buddy with whom Charles partied. The older Édouard Manet saw Charles, who became an Albrecht Dürer scholar, as an intellectual equal. Marcel Proust drew from Charles’s persona when he crafted the character Charles Swann in Remembrance of Things Past. Charles owned Gustave Moreau’s Jason from 1865, a great early symbolist painting that underscores how broadly his taste reached (Fig. 8).

From Gilded Age Paris, from flaneurs and aesthetes, we follow the netsuke to Vienna circa 1900. Charles gave the entire netsuke collection to his cousin Viktor and his new wife, Emmy, as a wedding present. Viktor’s and Charles’s worlds were different. Both men were very rich but Viktor was deeply involved in the family business. He and Emmy were establishment Viennese living in the Palais Ephrussi. We go from the milieu of the avant-garde to that of the grand bourgeoisie.

They and their lifestyle are metaphors for the Ringstrasse, the vast, bombastic redevelopment of central Vienna starting in the 1850s. Big money, much of it from prosperous Jewish families, spurred a new Vienna, with a new opera house, parliament building, museums the size of Roman temples, and palace-size homes for titans of commerce like the Ephrussis. The objects here focus on two architectural monuments: the Palais Ephrussi and the Stadttempel, the city’s main synagogue. There’s superb Judaica, mostly in the high Renaissance and Gothic revival styles that constituted establishment refinement. Viktor collected incunabula and other rare books, tapestries, and porcelain, too.

Hung salon-style, a group of paintings in the exhibition that were collected by the family in Vienna casts light on their own tastes in art. In contrast to Charles, the Vienna branch owned work by masters of the Austrian, German, and Netherlandish schools, dark and serious. Charles’s aesthetic tended toward the fresh and new, Viktor’s toward history, and history can be dim and heavy.

We learn about Vienna’s Jewish aristocracy, marriages among rich families, and an assimilation that was near-complete. Wedged in that gap between incomplete and complete was a ticking bomb.

In 1938 the Nazis made a brutal, sudden raid on the Ephrussi home and confiscated nearly all its contents. Viktor and Emmy had chosen to stay in Vienna after that year’s Anschluss, which united Germany and Austria politically. The family business and their home were there, after all. Over centuries, rich and poor Jews developed a talent for hoping for the best as well as a nose for sensing the worst that could happen. But Viktor’s and Emmy’s nose was off. They were rich, assimilated patriots, and model citizens. How could they not be valued? How could they be so hated?

The Palais Ephrussi was emptied. Viktor’s business was sold at a bargain basement price. The Nazis, though, overlooked the netsuke. In the ostentatious palace, the little netsuke were the odd art out. They reposed in a large, veneered vitrine in Emmy’s dressing room. There, for a generation, they bore silent witness to Emmy’s indulgence of high fashion, and most of her quality time with her four children. Over time, the Ephrussis’ maid, who stayed in the house as a servant of her new masters, smuggled them out one by one. She loyally kept them safe and returned them to Viktor and Emmy’s daughter. Circuitously, they were taken to Los Angeles, then to Tokyo, then to de Waal. They’re in New York now. Before these sweet, often playful figures unfolded a multitude of stories of love, loss, growing up, growing old, transience, and continuity.

The exhibition retells the diaspora of Viktor’s and Emmy’s children and their families through photographs and artifacts but most movingly through de Waal’s voice. He recorded passages of The Hare with Amber Eyes to which visitors can listen on specially provided headsets as they move through the show.

The Ephrussis make for a large cast. Some of them we like, some we don’t. De Waal’s research and book gives them heart and soul. The exhibition, probing and wide-reaching, goes one step further. It creates people we seem to know, people asserting strong personalities and their own presence, even as they’re tossed by the sea of world events.

The Hare with Amber Eyes will be on view at the Jewish Museum in New York from November 19 to May 15, 2022.